Gatka

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

| |

| Focus | Weaponry |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Punjab region in India and Pakistan |

| Olympic sport | No |

| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

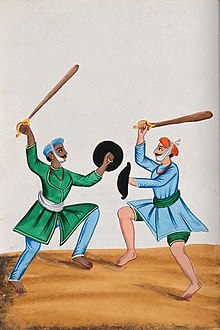

Gatka (Gurmukhi: ਗੱਤਕਾ; Shahmukhi: گَتّکا; Hindi: गतका; Urdu: گَتکا) is a form of martial art associated primarily with the Sikhs of the Punjab and other related ethnic groups, such as Hindkowans.[1][2] It is a style of stick-fighting, with wooden sticks intended to simulate swords.[3] The Punjabi name, gatka, refers to the wooden stick used and this term might have originated as a diminutive of a Sanskrit word, gada, meaning "mace".[4]

The stick used in Gatka is made of wood and is usually 91–107 cm (36–42 in) long, with a thickness of around 12.7 mm (0.50 in). It comes with a fitted leather hilt, 15–18 cm (5.9–7.1 in) and is often decorated with Punjabi-style multi-coloured threads.[2]

The other weapon used in the sport is a shield, natively known as phari. It is round in shape, measuring 23 by 23 centimetres (9.1 in × 9.1 in), and is made of dry leather. It is filled with either cotton or dry grass to protect the hand of player in case of full contact hit by an opponent.[2]

Gatka originated in the Punjab in the 15th century. There has been a revival during the later 20th century, with an International Gatka Federation was founded in 1982 and formalized in 1987, and gatka is now popular as a sport or sword dance performance art and is often shown during Sikh festivals.[5]

History

[edit]

Gatka's theory and techniques were taught by the Sikh gurus. It has been handed down in an unbroken lineage of ustāds (masters), and taught in many akharas (arenas) around the world. Gatka was employed in the Sikh wars and has been thoroughly battle-tested. It originates from the need to defend dharam (righteousness), but is also based on the unification of the spirit and body: miri piri). It is, therefore, generally considered to be both a spiritual and physical practice.[6]

After the Second Anglo-Sikh War, the art was banned by the new British administrators of India in the mid-19th century.[7][better source needed] During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Sikhs assisted the British in crushing the mutiny. As a consequence of this assistance, restrictions on fighting practices were relaxed, but the Punjabi martial arts which re-emerged after 1857 had changed significantly.[citation needed] The new style applied the sword-fighting techniques to the wooden training-stick. It was referred to as gatka, after its primary weapon. Gatka was used mainly by the British Indian Army in the 1860s as practice for hand-to-hand combat. The Ministry of Sports and Youth Affairs of the Government of India has included Gatka, with three other indigenous games, namely Kalaripayattu, Thang-Ta and Mallakhamba, as part of the planned Khelo India Youth Games 2021, expected to be held in Haryana.[8] This is a national sports event in India.[9]

The IOA plans to include Gatka in the 37th National Games of India in 2023 held in Goa.

Competition

[edit]Khel (meaning "sport" or "game") is the modern competitive aspect of gatka, originally used as a method of sword-training (fari‑gatka) or stick-fighting (lathi khela) in medieval times. While khel gatka is today most commonly associated with Sikhs, it has always been used in the martial arts of other ethno-cultural groups. It is still practiced in India and Pakistan by the Tanoli and Gujjar communities.[10][2]

Influence on Defendu

[edit]The Defendu system devised by Captain William E. Fairbairn and Captain Eric Anthony Sykes borrowed methodologies from Gatka, jujutsu, Chinese martial arts and "gutter fighting". This method was used to train soldiers in close-combat techniques at the Commando Basic Training Centre at Achnacarry in Scotland.[11]

See also

[edit]- Angampora

- Banshay

- Bataireacht

- Bōjutsu

- Commandos (United Kingdom)

- Hola Mohalla

- Indian martial arts

- Jūkendō

- Kalaripayattu

- Kendo

- Kenjutsu

- Krabi–krabong

- Kuttu Varisai

- Mardani khel

- Nihang

- Paika akhada

- Pehlwani

- Shastar Vidya

- Silambam

- Silambam Asia

- Special Operations Executive (SOE)

- Sqay

- Tahtib

- Thang-ta

- Varma kalai

- World Silambam Association

References

[edit]- ^ Yavari, Musa (26 February 2019). "'گتکا ہماری ثقافت ہے اور ہم نے اسے قائم رکھنا ہے'" [Gatka is our culture and we have to preserve it]. BBC Urdu (in Urdu). Shergarh, Punjab. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d Sadaqat, Muhammad (17 March 2019). "Gatka a centuries old art of self-defence". DAWN. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Donn F. Draeger and Robert W. Smith (1969). Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts. Kodansha International Limited.

- ^ Ananda Lal, The Oxford companion to Indian theatre, Oxford University Press (2004), ISBN 9780195644463, p. 129.

- ^ "Sikh martial art 'Gatka' takes the West by storm". The Hindu. New Delhi. Press Trust of India. 27 July 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Singh, Pashaura; Louis E. Fenech (March 2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. OUP Oxford. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- ^ "Ancient but Deadly: 8 Indian Martial Art Forms and Where You Can Learn Them". The Better India. 10 January 2017. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Sports Ministry approves inclusion of four indigenous games in Khelo India Youth Games". The Hindu. PTI. 20 December 2020. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Hussain, Sabi (13 September 2018). "Khelo India: Khelo India to become Khelo India Youth Games with IOA on board". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Gatka is our culture and we have to maintain it". BBC. 26 February 2019. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Peter-Michel, Wolfgang (2011). The Fairbairn-Sykes fighting knife: Collecting Britain's most iconic dagger. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military History. ISBN 978-0764337635.

External links

[edit]- Nanak Dev Singh Khalsa & Sat Katar Kaur Ocasio-Khalsa (1991) Gatka as taught by Nanak Dev Singh, Book One – Dance of the Sword (2nd Edition). GT International, Phoenix, Arizona. ISBN 0-89509-087-2

- "The Fairbairn Sykes Fighting Knives". X-Daggers. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- Olaf Janson (2015) Fairbairn–Sykes fighting knife: The famous fighting knife used by British commandos and SOE during WW2. Gothia Arms Historical Society