Children's Crusade

The Children's Crusade was a failed popular crusade by European Christians to establish a second Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in the Holy Land in the early 13th century. Some sources have narrowed the date to 1212. Although it is called the Children's Crusade, it never received the papal approval from Pope Innocent III to be an actual Crusade. The traditional narrative is likely conflated from a mix of historical and mythical events, including the preaching of visions by a French boy and a German boy, an intention to peacefully convert Muslims in the Holy Land to Christianity, bands of children marching to Italy, and children being sold into slavery in Tunis. The crusaders of the real events on which the story is based left areas of Germany, led by Nicholas of Cologne, and Northern France, led by Stephen of Cloyes.

Accounts

[edit]Traditional accounts

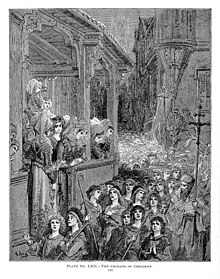

[edit]The variants of the long-standing story of the Children's Crusade have similar themes.[1] A boy begins to preach in either France or Germany, claiming that he had been visited by Jesus, who instructed him to lead a Crusade in order to peacefully convert Muslims to Christianity. Through a series of portents and miracles, he gains a following of up to 30,000 children. He leads his followers south towards the Mediterranean Sea, in the belief that the sea would part on their arrival, which would allow him and his followers to walk to Jerusalem. This does not happen. The children are given free passage on boats by two French merchants (Hugh the Iron and William of Posqueres) to as many of the children as are willing to pay. The pilgrims are then mainly taken to Tunisia, where they are sold into slavery by the merchants, though some die in a shipwreck on San Pietro Island off Sardinia during a gale.

Modern accounts

[edit]According to more recent researchers, there seem to have actually been two separate movements of people (including adults) in 1212 from Germany and France.[2][1] The similarities of the two allowed later chroniclers to combine and embellish the tales.

Nicholas of Cologne in Germany

[edit]In the first movement, Nicholas, a shepherd from the Rhineland in Germany,[3] tried to lead a group across the Alps and into Italy in the early spring of 1212. Nicholas said that the sea would open up before them just as the Lord had done for the Israelites and allow his followers to cross into the Holy Land.[4] Rather than intending to fight the Saracens, he said that the Muslim kingdoms would be defeated when their citizens converted to Christianity.[3] His disciples went off to preach the call for the "Crusade" across the German lands, and they massed in Cologne after a few weeks. Splitting into two groups, the crowds took different roads through Switzerland. Two out of every three people on the journey died, while many others returned to their homes.[3] About 7,000 arrived in Genoa in late August. They immediately marched to the harbour, expecting the sea to divide before them; when it did not many became bitterly disappointed. A few accused Nicholas of betraying them, while others settled down to wait for God to change his mind, since they believed that it was unthinkable that he would not eventually do so. The Genoese authorities were reportedly impressed by the group, and they offered citizenship to those who wished to settle in their city. Most of the would-be Crusaders took up this opportunity.[3] Nicholas refused to say he was defeated and travelled to Pisa, his movement continuing to break up along the way. In Pisa, two ships directed to Palestine agreed to embark several of the children who, perhaps, managed to reach the Holy Land.[5] Nicholas and a few loyal followers, instead, continued to the Papal States, where they met Pope Innocent III. The remaining ones departed for Germany after the Pontiff exhorted them to be good and to return home to their families. Nicholas did not survive the second attempt across the Alps; back home his father was arrested and hanged under pressure from angry families whose relatives had perished while following the children.[3]

Some of the most dedicated members of this Crusade were later reported to have wandered to Ancona and Brindisi; none are known to have reached the Holy Land.[3]

Stephen of Cloyes in France

[edit]The second movement was led by a twelve-year-old[3] French shepherd boy named Stephen (Étienne) of Cloyes, who said in June that he bore a letter for the king of France from Jesus who was disguised as a poor pilgrim.[6][4] Large gangs of youths around his age were drawn to him, most of whom claimed to possess special gifts of God and thought themselves miracle workers. Attracting a following of over 30,000, including adults, but mostly children, he went to Saint-Denis, where he was reported to cause miracles. On the orders of Philip II, advised by the University of Paris, the people were implored to return home. Philip himself did not appear impressed, especially since his unexpected visitors were led by a mere child, and refused to take them seriously. Stephen, however, was not dissuaded and began preaching at a nearby abbey. From Saint-Denis, Stephen travelled around France, spreading his messages as he went, promising to lead charges of Christ to Jerusalem. Although the Church was skeptical, many adults were impressed by his teaching.[3] Few of those who initially joined him possessed his activeness; it is estimated that there were fewer than half the initial 30,000 remaining, a figure that was shrinking rapidly, rather than growing as perhaps anticipated.

At the end of June 1212, Stephen led his largely juvenile Crusaders from Vendôme to Marseilles. They survived by begging for food, while the vast majority seem to have been disheartened by the hardship of this journey and returned to their families.[3]

Two French merchants (Hugh the Iron and William of Posqueres) offered to carry any children that were willing to pay a small fee by boat. They were then taken to Tunisia, where they were sold into slavery by the merchants. However, some died in a shipwreck on San Pietro Island off Sardinia during a gale.[citation needed]

Historiography

[edit]Sources

[edit]According to Peter Raedts, professor in Medieval History at the Radboud University Nijmegen, there are about 50 sources from the period that talk about the crusade, ranging from a few sentences to half a page.[2] Raedts categorizes the sources into three types depending on when they were written:[2]

- Contemporary sources written by 1220;

- Sources written between 1220 and 1250 (the authors could have been alive at the time of the crusade but wrote their memories down later);

- Sources written after 1250 by authors who received their information second or third hand.

Raedts does not consider the sources after 1250 to be authoritative, and of those before 1250, he considers only about 20 to be authoritative. It is only in the later non-authoritative narratives that a "children's crusade" is implied by such authors as Vincent of Beauvais, Roger Bacon, Thomas of Cantimpré, Matthew Paris and many others. At least one source, that of a man simply known as Otto the last puer, was written by an individual who claimed to have participated in the Children's Crusade.[7]

Historical studies

[edit]Prior to Raedts's study of 1977, there had only been a few historical publications researching the Children's Crusade. The earliest were by the Frenchman G. de Janssens (1891) and the German Reinhold Röhricht (1876). They analyzed the sources but did not analyze the story. American medievalist Dana Carleton Munro (1913–14), according to Raedts, provided the best analysis of the sources to date and was the first to significantly provide a convincingly sober account of the Crusade stripped of legends.[8] Later, J. E. Hansbery (1938–9) published a correction of Munro's work, but it has since been discredited as based on an unreliable source.[2] German psychiatrist Justus Hecker (1865) did give an original interpretation of the crusade, but it was a polemic about "diseased religious emotionalism" that has since been discredited.[2]

P. Alphandery (1916) first published his ideas about the crusade in 1916 in an article which was later published in book form in 1959. He considered the story of the crusade to be an expression of the medieval cult of the Innocents, as a sort of sacrificial rite in which the Innocents gave themselves up for the good of Christendom; however, he based his ideas on some of the most untrustworthy sources.[9]

Adolf Waas (1956) saw the Children's Crusade as a manifestation of chivalric piety and as a protest against the glorification of the holy war.[10] H. E. Mayer (1960) further developed Alphandery's ideas of the Innocents, saying children were the chosen people of God because they were the poorest; recognizing the cult of poverty, he said that "the Children's Crusade marked both the triumph and the failure of the idea of poverty."[11] Giovanni Miccoli (1961) was the first to note that the contemporary sources did not portray the participants as children. It was this recognition that undermined all other interpretations,[12] except perhaps that of Norman Cohn (1957) who saw it as a chiliastic movement in which the poor tried to escape the misery of their everyday lives.[13] In his book Children's Crusade: Medieval History, Modern Mythistory (2008), Gary Dickson discusses the growing number of "impossibilist" movements across Western Europe at the time. Infamous for their shunning of any form of wealth and refusing to join a monastery, they would travel in groups and rely upon small donations or meals from those who listened to their sermons to survive. Excommunicated by the Pope, they were forced to wander and likely made up a large portion of what is called the "Children's Crusade". After the crusade failed, the Pope stated that the devotees of Nicholas and Stephen had shamed all of the Christian leaders.[14]

Historians have put the crusade in the context of the role of teenage boys in medieval warfare.[15] Literary scholars have explored its role in the evolution of the tale of the Pied Piper.[16]

Popular accounts

[edit]Beyond the scientific studies there are many popular versions and theories about the Children's Crusades. Norman Zacour in the survey A History of the Crusades (1962) generally follows Munro's conclusions, and adds that there was a psychological instability of the age, concluding the Children's Crusade "remains one of a series of social explosions, through which medieval men and women—and children too—found release".

Steven Runciman gives an account of the Children's Crusade in his A History of the Crusades.[17] Raedts notes that "Although he cites Munro's article in his notes, his narrative is so wild that even the unsophisticated reader might wonder if he had really understood it." Donald Spoto, in a 2002 book about Saint Francis of Assisi, said monks were motivated to call them children, and not wandering poor, because being poor was considered pious and the Church was embarrassed by its wealth in contrast to the poor. This, according to Spoto, began a literary tradition from which the popular legend of children originated. This idea closely follows H. E. Mayer.

Revisionism

[edit]The Dutch historian Peter Raedts, in a study published in 1977, was the first to cast doubt on the traditional narrative of these events. Many historians came to believe that they were not (or not primarily) children, but multiple bands of "wandering poor" in Germany and France. This comes in large part from the words "parvuli" or "infantes" found in two accounts of the event from William of Andres and Alberic of Troisfontaines. No other accounts from the time period suggest an age at all, but the connotation with the two words give an entirely separate meaning. Medieval writers often split up a life into four major parts with a variety of age ranges associated to them. The Church then co-opted this classification to a societal coding, with the expression referring to wage workers or labourers who were young and had no inheritance. The Chronica regia Coloniensis, written in 1213 (a year after the crusade was said to have taken place), refers to crusaders having "left the plows or carts which they were driving, [and] the flocks which they were pasturing", adding to the idea of it being not "puerti" the age, but "puerti" the societal moniker. Another spelling, pueri, translates precisely into children, but indirectly means "the powerless". A number of them tried to reach the Holy Land but others never intended to do so. Early accounts of events, of which there are many variations told over the centuries, are, according to this theory, largely apocryphal.[clarification needed][2][1]

Raedts "wandering poor" without children account was revised in 2008 by Gary Dickson who maintained that while it was not made up entirely of actual children, they did exist and played a key role.[14][18]

In the arts

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2023) |

Many works of art reference the Children's Crusade; this list is focused on works that are set in Middle Ages and focus primarily on a re-telling of the events. For other uses see Children's Crusade (disambiguation).

Books

[edit]- La Croisade des enfants ("The Children's Crusade", 1896) by Marcel Schwob.

- Pied Piper (1930), a novel by Daphne Muir (also published with title The Lost Crusade)

- "The Chalet School and Barbara" Elinor Brent-Dyer (1954), the Christmas play references the Children's crusade.

- The Children's Crusade (1958), children's historical novel by Henry Treece, includes a dramatic account of Stephen of Cloyes attempting to part the sea at Marseille.

- The Gates of Paradise (1960), a novel by Jerzy Andrzejewski centres on the crusade, with the narrative employing a stream of consciousness technique.

- The March of the Innocents (1964), a novel by John Wiles which retells the traditional French story of Stephen of Cloyes, with the relationships between the protagonists being more important than the narrative. Very gritty, especially when describing the excesses of the Albigensian Crusade.

- Sea and Sunset (1965), a short story by Yukio Mishima (part of a collection entitled Acts of Worship), portrayed an old French man who took part in the Children's Crusade as a boy and, through complicated circumstances, wound up in Japan.

- Slaughterhouse-Five (or, The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death), is a 1969 novel by American author Kurt Vonnegut, telling the story of Billy Pilgrim, a young American soldier, and his experience during World War II. The alternative title references The Children's Crusade and compares it to World War II, suggesting it was yet another war fought by children who were drafted into the army at a very young age.

- Crusade in Jeans (Dutch: Kruistocht in spijkerbroek), is a 1973 novel by Dutch author Thea Beckman and a 2006 film adaptation about the Children's Crusade through the eyes of a time traveler.

- An Army of Children (1978), a novel by Evan Rhodes that tells the story of two boys, a Catholic and a Jew, partaking in the Children's Crusade.

- Angeline (2004), a novel by Karleen Bradford about the life of a girl, Angeline, a priest, and Stephen of Cloyes after they are sold into slavery in Cairo.

- The Crusade of Innocents (2006), a novel by David George, suggests that the Children's Crusade may have been affected by the concurrent crusade against the Cathars in Southern France, and how the two could have met.

- The Scarlet Cross (2006), a novel for youth by Karleen Bradford.

- 1212: Year of the Journey (2006), a novel by Kathleen McDonnell. Young adult historical novel.

- Sylvia (2006), a novel by Bryce Courtney. Follows a teenage girl during the crusades.

- Crusade (2011), a children's historical novel by Linda Press Wulf.

- The True History of the Children's Crusade (2013), a graphic novel by Privo di Casato, narrated from the perspective of Stephen of Cloyes.

- The Children's Boat (2014) a novel by Mario Vargas Llosa

- 1212 (1985), a quartet of historical novels aimed at children and young adults by Danish author and journalist Carsten Overskov.

- Matrix (2021), a novel by Lauren Groff. Follows a fictionalized version of Marie de France and her thoughts on the crusade.

Comics

[edit]- The Children's Crusade, an overarching title that covers a seven-issue comic crossover published for Vertigo Comics which seemingly links the event to other events such as the true event that inspired the story of the Pied Piper. Published in 2015 by Vertigo Comics as Free Country: A Tale of the Children's Crusade.

- Innocent shōnen jūjigun (インノサン少年十字軍, The Crusade of the Innocent Boys), a manga written by Usamaru Furuya (Manga F Erotics, 2005~2011, 3 volumes).

Plays

[edit]- Cruciada copiilor (en. Children's Crusade) (1930), a play by Lucian Blaga based upon the Crusade.

- The Children's Crusade (1973), a play by Paul Thompson first produced at the Cockpit Theatre (Marylebone), London by the National Youth Theatre.

- A Long March To Jerusalem (1978), a play by Don Taylor about the story of the Children's Crusade.

- The Fire of Roses (2003), a novel by Gregory Rinaldi

- Crusade of Tears (2004), a novel from the series Journey of Souls by C.D. Baker.[citation needed]

Musicals

[edit]- Crusade (1998), a musical by Craig Christie and Wayne Hosking.

Music

[edit]- La Croisade des Enfants (1902), a seldom-performed oratorio by Gabriel Pierné, featuring a children's chorus, based on La croisade des enfants ("The Children's Crusade") by Marcel Schwob.

- The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi (1963), a dramatic cantata for two soloists, chorus, children's chorus and orchestra with words and music by Gian Carlo Menotti, focused on a Bishop's regret for having blessed the doomed journey of the children.

- "Children's Crusade", a contemporary opera by R. Murray Schafer, first performed in 2009.

- "Children's Crusade", a song by Sting from his 1985 album The Dream of the Blue Turtles. Not about the event as such, but using the name as an analogy.

- "Children's Crusade", a song by Tonio K from his 1988 album Notes from the Lost Civilization.

- "Untitled Track", a song by The Moon Lay Hidden Beneath a Cloud, found originally on the 10" EP Yndalongg (1996), then re-released as the track "XII" on the CD Rest on Your Arms Reversed (1999), which tells a version of the story of the Children's Crusade and implies that the visions were inspired by the Devil.

- The Diabolic Procession (2006), a concept album by Chicago hard rock band Bible of the Devil, which "addresses the fable of the Children's Crusades as a metaphor for our troubled times."[19]

- Seminal Australian progressive rock band Cinema Prague named their 1991 tour "The Children's Crusade" as a satirical reference to the ages of the members of the band, for at the time, most of the band were still teenagers.

Movies

[edit]- Gates to Paradise (1968), a film version by Andrzej Wajda of the Jerzy Andrzejewski novel.

- Lionheart (1987), a historical/fantasy film, loosely based on the stories of the Children's Crusade.

- La Croisade des enfants (1988), a two-parts television film directed by Serge Moati and broadcast on FR3.

- Crusade in Jeans, a.k.a. A March Through Time (2006), a motion picture predicated on unintentional travel by a soccer-playing boy from the modern Netherlands to the legendary German Children's Crusade led by Nicholas.

Video Games

[edit]- In Clive Barker's Jericho (2007), The Children's Crusade forms a crucial part of the game's lore as one of the tragedies used to summon the Firstborn, the game's main antagonist. The game also depicts the Crusade as having been secretly sanctioned by Pope Innocent III, although later disavowed and covered up when the crusaders were slaughtered. Additionally, the slain children appear in the game as ghoulish enemies seeking revenge for their deaths.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c Russell, Frederick H. (1989). "Children's Crusade". In Strayer, Joseph R. (ed.). Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Vol. 4. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c d e f Raedts, Peter (1977). "The Children's Crusade of 1213". Journal of Medieval History. 3 (4): 279–323. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(77)90026-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bridge, Antony. The Crusades. London: Granada Publishing, 1980. ISBN 0-531-09872-9

- ^ a b "Children's Crusade | European history | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1971). A History of the Crusades. Vol III. Pelican Books. p. 142.

- ^ Hansbery, Joseph E. (1938). "The Children's Crusade". The Catholic Historical Review. 24 (1): 30–38. ISSN 0008-8080.

- ^ Dickson, Gary (2008). Children's Crusade: Medieval History, Modern Mythistory

- ^ Munro, D. C. (1914). "The Children's Crusade". American Historical Review. 19: 516–524.

- ^ Alphandery, P. (1954). La Chrétienté et l'idée de croisade. 2 vols.

- ^ Waas, A. (1956). Geschichte der Kreuzzüge

- ^ Mayer, H.E. (1972). The Crusades

- ^ Miccoli, G. (1961). "La crociata dei fancifulli". Studi medievali. Third Series, 2:407–43

- ^ Norman Cohen (1957). The Pursuit of the Millennium. New Jersey: Essential Books.

- ^ a b Dickson, Gary (2008). Children's Crusade: Medieval History, Modern Mythistory.

- ^ Kelly DeVries, "Teenagers at War During the Middle Ages" in The Premodern Teenager: Youth in Society, 1150–1650 (2002) ed by Konrad Eisenbichler pp 207–223.

- ^ Bernard Queenan, "The Evolution of the Pied Piper," Children's Literature (1978) 7#1 pp: 104–114.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1951). "The Children's Crusade", from A History of the Crusades.

- ^ Andrew Holt (2019). The World of the Crusades: A Daily Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 149.

- ^ "The Diabolic Procession - Bible of the Devil". Bandcamp. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- DeVries, Kelly. "Teenagers at War During the Middle Ages" in The Premodern Teenager: Youth in Society, 1150–1650 (2002) ed by Konrad Eisenbichler, pp 207–223.

- Dickson, Gary. "Stephen of Cloyes, Philip Augustus, and the Children’s Crusade of 1212." in Journeys toward God: Pilgrimage and Crusade, ed. Barbara N. Sargent-Baur (Kalamazoo, Mich.: Medieval Institute Publications, 1992): 83–105.

- Dickson, Gary. The Children's Crusade: Medieval History, Modern Mythistory, 2008, Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-9989-4

- Munro, Dana C (1914). "The Children's Crusade". American Historical Review. 19 (3): 516–524. doi:10.2307/1835076. JSTOR 1835076.

- Queenan, Bernard. "The Evolution of the Pied Piper." Children's Literature (1978) 7: 104–114. (DOI: 10.1353/chl.0.0173)

- Raedts, Peter. "The Children's Crusade of 1212", Journal of Medieval History, 3 (1977), summary of the sources, issues and literature.

- Russell, Frederick. "Children's Crusade", Dictionary of the Middle Ages, 1989, ISBN 0-684-17024-8

- Scheck, Raffael (1988). "Did the Children's Crusade of 1212 really consist of children? Problems of writing childhood history". The Journal of Psychohistory. 16: 176–182.

- Chronica Regiae Coloniensis Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, a (supposedly) contemporary source. From the Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- The Children's Crusade on Medieval Archives Podcast

- The Children's Crusade, from History House

- Cardini Franco, Del Nero Domenico, La crociata dei fanciulli, Giunti Editore, 1999, ISBN 88-09-21770-5

- "In the Footsteps of a Children's Crusade". New York Times. 1987.

- Childrens Crusades | Medieval Chronicles