Dawson massacre

| Dawson Massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Woll Expedition | |||||||

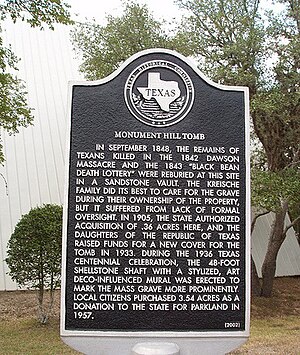

A plaque at Monument Hill Park marking the graves of those killed in the Dawson Massacre and the Black Bean Incident. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 54 militia |

500 cavalry 2 artillery pieces | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

36 killed 15 captured |

30 killed 60–70 wounded[1] | ||||||

|

| |||||||

The Dawson massacre, also called the Dawson expedition, was an incident in which 36 Texian militiamen were killed by Mexican soldiers on September 17, 1842[2] near San Antonio de Bexar (now the U.S. city of San Antonio, Texas). The event occurred during the Battle of Salado Creek, which ended with a Texian victory.[3] This was among numerous armed conflicts over the area between the Rio Grande and Nueces rivers, which the Republic of Texas tried to control after achieving independence in 1836.

Background

[edit]On April 21, 1836, the independence of the Republic of Texas was secured by a decisive victory over the Mexican Army at the Battle of San Jacinto. Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its southern border but had sufficient military power to control only land north of the Nueces River. Although Antonio López de Santa Anna, the ruler of Mexico, signed the Treaties of Velasco ceding Texas territory from Mexican control, the treaty was never ratified by the Mexican Government. Santa Anna repudiated the treaty once he was released from Texan custody.

Mexican forces and allied Cherokee guerrillas under Vicente Cordova and Chicken Trotter continued to resist Texan attempts to occupy the area between the Rio Grande and Nueces rivers. For the Cherokees, it was a war of vengeance following the massacre of Cherokee and Delaware Indians by Texas Army regulars in the summer of 1839. For the Mexicans, it was to prove they could return to Texas at will.

On September 11, 1842, a Mexican force of 1,600 entered San Antonio and took control there, with minimal resistance from the Texans. When the news of the fall of San Antonio reached Gonzales, Mathew Caldwell formed a militia of 210 men and marched toward San Antonio. Caldwell's troops made camp about thirteen miles east of the town, near Salado Creek, and planned their attack on the Mexicans.[4][5]

Massacre

[edit]On September 17, Caldwell sent a small band of rangers to draw the Mexicans toward the battlefield he had chosen. At least 1,000 Mexican soldiers moved out of San Antonio to attack the Texans. A separate company of 54 Texans, mostly from Fayette County, under the command of Nicholas Mosby Dawson, arrived at the battlefield and began advancing on the rear of the Mexican Army. The Mexican commander, General Adrián Woll, afraid of being surrounded, sent 500 of his cavalry soldiers and two cannons to attack the group.[3] The Texans were able to hold their own against the Mexican rifles, but once the cannons got within range, their fatalities mounted quickly. Dawson realized the situation was hopeless and raised a white flag of surrender.

In the fog of war, both sides continued to fire and Dawson was killed. The battle was over after a little more than one hour. It ended with 36 Texans dead, fifteen captured and two escaped. At the front, Caldwell's men had repelled the Mexican attacks and inflicted heavy casualties. Woll was forced to retreat to San Antonio and then towards the Rio Grande.

The next morning Caldwell's troops located the Dawson battleground and buried the dead Texans in shallow graves. The dead Mexicans were not buried. Caldwell then unsuccessfully pursued Woll's forces south as they retreated from San Antonio. Caldwell returned to San Antonio, after the Mexicans successfully recrossed the Rio Grande.[4][5]

Legacy

[edit]In late summer of 1848 (after Texas had become a U.S. state), a group of La Grange citizens retrieved the remains of the men killed in the Dawson Massacre from their burial site near Salado Creek. These remains, and the remains of the men killed in the failed Mier Expedition, were reinterred in a common tomb in a concrete vault on a bluff one mile south of La Grange. The grave site is now part of the Monument Hill and Kreische Brewery State Historic Sites.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "TSHA | Dawson Massacre". tshaonline.org. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "The Mier Expedition by George Lord". Archived from the original on 2010-12-05. Retrieved 2011-01-12.

- ^ a b "Dawson Massacre". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ a b "Salado Creek, Battle Of". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ a b "Battle of the Salado Creek 1842". jack0204.tripod.com. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ "Interpretive Guide to Monument Hill/Kreische Brewery State Historic Sites" (PDF). Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- Abolafia-Rosenzweig, Mark. The Dawson and Mier Expeditions and Their Place in Texas History. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 2nd printing April 1991.