New Castle, New Hampshire

New Castle, New Hampshire | |

|---|---|

Fort Point Light from Ocean Street | |

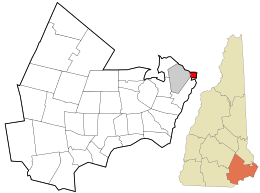

Location in Rockingham County and the state of New Hampshire. | |

| Coordinates: 43°04′20″N 70°42′58″W / 43.07222°N 70.71611°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Hampshire |

| County | Rockingham |

| Incorporated | May 30, 1693[1] |

| Government | |

| • Select Board |

|

| • Town Administrator | Michael Tully |

| Area | |

• Total | 2.27 sq mi (5.88 km2) |

| • Land | 0.81 sq mi (2.09 km2) |

| • Water | 1.46 sq mi (3.78 km2) 64.4% |

| Elevation | 30 ft (9 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 1,000 |

| • Density | 1,237/sq mi (477.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP code | 03854 |

| Area code | 603 |

| FIPS code | 33-50980 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0873676 |

| Website | www |

New Castle is a town in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 1,000 at the 2020 census.[4] It is the smallest and easternmost town in New Hampshire and the only one located entirely on islands. It is home to Fort Constitution Historic Site, Fort Stark Historic Site, and the New Castle Common, a 31-acre (13 ha) recreation area on the Atlantic Ocean. New Castle is also home to a United States Coast Guard station, as well as the historic Wentworth by the Sea hotel.

History

[edit]The main island on which the town sits is the largest of several at the mouth of the Piscataqua River and was originally called "Great Island". Settled in 1623, an earthwork defense was built on Fort Point which would evolve into Fort William and Mary (rebuilt in 1808 as Fort Constitution). Chartered in 1679 as a parish of Portsmouth, it was incorporated on May 30, 1693, and was named "New Castle" after the fort. Until 1719 it included Rye, then called "Sandy Beach", which was set off as a parish. The principal industries were trade, tavern-keeping, and fishing. There was also agriculture, using the abundant seaweed as fertilizer.[5]: 594–6

Beginning on June 11, 1682, Great Island experienced a supernatural event—a lithobolia, or "Stone-Throwing Devil", recorded in a 1698 London pamphlet by Richard Chamberlain. On a Sunday night at about 10 o'clock, the tavern home of George Walton, an early settler and planter, was showered with stones thrown "by an invisible hand". Windows were smashed, and the spit in the fireplace leapt into the air, then came down with its point stuck in the back log. When a member of the household retrieved the spit, it flew out the window of its own accord. The gate outside was discovered off its hinges.[6][7]: 7–12, 66–67 Rev. Cotton Mather took an interest in the phenomenon, reporting that:

- "This disturbance continued from day to day; and sometimes a dismal hollow whistling would be heard, and sometimes the trotting and snorting of a horse, but nothing to be seen.... A man was much hurt by some of the stones. He was a Quaker, and suspected that a woman, who charged him with injustice in detaining some land from her did, by witchcraft, occasion these preternatural occurrences. However, at last they came to an end."

The "Stone-Throwing Devil" created quite a sensation on Great Island. Hundreds of stones mysteriously rained down on George Walton's tavern, as well as onto him and others in the area over the entire summer. Yet no one ever came forward who saw anyone throwing the stones. Many other mysterious events also occurred at that time. Demonic voices were heard, and items were flung about inside Walton's tavern. Prominent Boston minister Increase Mather described the strange events in his book Illustrious Providences.[7]: xiii, 4–5, 7–12

George Walton, who was in a property boundary dispute with his neighbor, accused her of witchcraft. She, in turn, accused him of being a wizard. Others in the area may also have had reasons to throw stones at Walton. He was a Quaker. Quakers were looked upon with great suspicion by Puritans, and just being a Quaker was a crime. Walton was a successful innkeeper, merchant, and lumberman, and became the largest landowner on the island. Walton was envied by his less industrious neighbors. He was involved in a number of lawsuits over business and property disputes. He also had two Native American employees, which would have caused great concern so soon after war with the Indians (King Philip's War) and because of the uneasy peace that existed. His tavern customers included a variety of rowdy outsiders, including "godless" fishermen, who were considered undesirables by others on the island. Regardless of what caused Walton and his inn to be the victim of a months-long rain of stones, it was the first major outbreak of apparent witchcraft in America.[6][7]: 4–5, 7–12, 48–51, 58, 66

News of it traveled throughout America and England. Within a few years, accusations of witchcraft would occur in other New England towns, culminating in the famous witch trials in Salem, Massachusetts.[7]: 177–201

Fort William and Mary was the site of one of the first acts of the American Revolution. On the afternoon of December 14, 1774, colonists arrived aboard gundalows (sailing barges) and raided the fort. Severely outnumbered, Captain John Cochran and the fort's five soldiers surrendered, whereupon the rebels loaded onto a boat 100 barrels of gunpowder. The boat was floated up the Piscataqua River and the powder offloaded for transport to inland towns, including Durham, where the ammunition was stored in the cellar of the Congregational church. The next day, the colonists returned to the fort and removed 16 of the lighter cannon and all small arms. The gunpowder was used at the 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill.[5]: 474–477

A new route to the island was created in 1821 when three bridges (now two bridges and a causeway) connected Frame Point in Portsmouth with the northwestern corner of Great Island. Previously, a bridge on the southwestern point had been the only way to reach New Castle without a boat. The community was then an overlooked fishing village, which helped preserve its colonial architecture. However, in 1874 the Hotel Wentworth was built atop a hill with a view of Little Harbor and the ocean. After early financial difficulties, the establishment was purchased and elaborately refurbished in Second Empire style by Portsmouth alemaker and hotelier Frank Jones. It became the area's most fashionable resort, growing in size until it was a village unto itself. When President Theodore Roosevelt mediated the 1905 Treaty of Portsmouth to end the Russo-Japanese War, envoys from both countries stayed at the Wentworth by the Sea, ferried by launch to negotiations held at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. The hotel was a setting for the 1999 movie, In Dreams.

-

Bo'sun Allen House c. 1905

-

Fort Point Light c. 1908

-

Fort Constitution in 1905

-

Walbach Tower in 1908

-

The Wentworth c. 1920

-

Piscataqua River c. 1913

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 2.3 square miles (5.9 km2), of which 0.81 square miles (2.1 km2) are land and 1.5 square miles (3.8 km2) are water, comprising 64.4% of the town.[2] New Castle occupies an archipelago, consisting of one main island (Great Island) and several smaller islands surrounded by the Piscataqua River and Atlantic Ocean. The main channel of the Piscataqua passes around the north and east sides of Great Island, while Little Harbor is to the south and the smaller islands within Portsmouth Harbor are to the west. The southeastern end of the island, at Fort Stark, faces the Atlantic. The highest point of land is at the Wentworth by the Sea hotel, where the elevation reaches 60 feet (18 m) above sea level.

Adjacent municipalities

[edit]- Kittery, Maine (north)

- Rye (southwest)

- Portsmouth (west)

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 534 | — | |

| 1800 | 524 | −1.9% | |

| 1810 | 592 | 13.0% | |

| 1820 | 932 | 57.4% | |

| 1830 | 850 | −8.8% | |

| 1840 | 742 | −12.7% | |

| 1850 | 891 | 20.1% | |

| 1860 | 692 | −22.3% | |

| 1870 | 667 | −3.6% | |

| 1880 | 610 | −8.5% | |

| 1890 | 488 | −20.0% | |

| 1900 | 581 | 19.1% | |

| 1910 | 624 | 7.4% | |

| 1920 | 728 | 16.7% | |

| 1930 | 378 | −48.1% | |

| 1940 | 542 | 43.4% | |

| 1950 | 583 | 7.6% | |

| 1960 | 823 | 41.2% | |

| 1970 | 975 | 18.5% | |

| 1980 | 936 | −4.0% | |

| 1990 | 840 | −10.3% | |

| 2000 | 1,010 | 20.2% | |

| 2010 | 968 | −4.2% | |

| 2020 | 1,000 | 3.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[8] | |||

As of the census of 2020,[4] there were 1,000 people in 436 households within the town. The population density was 1,250 inhabitants per square mile (480/km2). There were 525 housing units at an average density of 656.3 per square mile (253.4/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 94.9% White, 0.4% African American, 0.9% Asian, and 3.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.7% of the population.

At the 2010 census, 22.1% of households had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61.6% were married couples living together, 5.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.1% were non-families. 23.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.65.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 17.8% under the age of 18, 3.4% from 18 to 24, 20.8% from 25 to 44, 34.0% from 45 to 64, and 24.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 50 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.1 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $83,708, and the median income for a family was $93,290. Males had a median income of $57,375 versus $35,568 for females. The per capita income for the town was $67,695. None of the families and 0.6% of the population were living below the poverty line, including none under 18 and none of those over 65. New Castle was New Hampshire's wealthiest town in terms of per capita income.

Sites of interest

[edit]

- Fort Constitution State Historic Site

- Fort Stark State Historic Site

- New Castle, NH Historical Society at the Old Library Museum

- Portsmouth Harbor Light (or Fort Point Light)

Notable people

[edit]- Harriet Ryan Albee (1829-1873), social reformer and philanthropist

- J.D. Barker (born 1971), NY Times and international bestselling author[9]

- Samantha Brown (born 1970), travel guide TV host

- George Frost (1720–1796), seaman, jurist, representative to the Continental Congress

- Benjamin Randall (1749–1808), religious leader

- Duncan Robinson (born 1994), NBA player for the Miami Heat

- Edmund C. Tarbell (1862–1938), American impressionist painter

References

[edit]- ^ A Complete Descriptive and Statistical Gazetteer of the United States of America. Sherman & Smith. 1843. p. 448.

- ^ a b "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files – New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 29, 2021.

- ^ "Town of New Castle". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b "Explore Census Data".

- ^ a b Coolidge, Austin J.; John B. Mansfield (1859). A History and Description of New England. Boston, Massachusetts: A.J. Coolidge. p. 594.

coolidge mansfield history description new england 1859.

- ^ a b Palmer, Ansell W., ed. Piscataqua Pioneers: Selected Biographies of Early Settlers in Northern New England, pp. 446-7, Piscataqua Pioneers, Portsmouth, NH, 2000. ISBN 0-9676579-0-3.

- ^ a b c d Baker, Emerson W. The Devil of Great Island, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2007.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "International Bestselling Author J.D. Barker Moves to New Castle, NH". JDBarker.com. June 14, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- John Albee, New Castle, Historic and Picturesque; Cupples, Upham & Company, Boston, Massachusetts 1884

- Charles W. Brewster, Rambles About Portsmouth; C. W. Brewster & Son; Portsmouth, New Hampshire 1859

- Thomas F. Kehr, "The Seizure of his Majesty's Fort William and Mary at New Castle, New Hampshire, December 14–15, 1774," Essays and Articles, New Hampshire Society of the Sons of the American Revolution at [1]

- Thompson, Connie. Piscataqua Pioneers: Selected Biographies of Early Settlers in Northern New England, Piscataqua Pioneers, 2000

- White, Anna B. History of New Castle, New Hampshire, 1984. Carrol White, ed., 2012