Johnny Mnemonic (film)

| Johnny Mnemonic | |

|---|---|

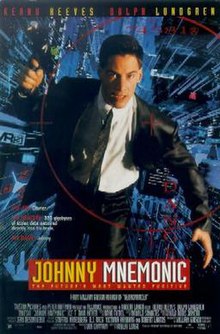

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Longo |

| Screenplay by | William Gibson |

| Based on | Johnny Mnemonic by William Gibson |

| Produced by | Don Carmody |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | François Protat |

| Edited by | Ronald Sanders[1] |

| Music by |

|

Production company | Johnny Mnemonic Productions[2] |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 96 minutes[4] |

| Countries | |

| Language | English[2] |

| Budget | $26 million[5] |

| Box office | $19 million (US)[5] |

Johnny Mnemonic is a 1995 cyberpunk action film[6] directed by Robert Longo in his feature directorial debut. William Gibson, who wrote the 1981 short story, wrote the screenplay. The film, set in 2021, portrays a dystopian future racked by a tech-induced plague, awash with conspiracies, and dominated by megacorporations and organized crime. Keanu Reeves plays Johnny, a data courier with an overloaded brain implant designed to securely store confidential information. Takeshi Kitano portrays a yakuza affiliated with a megacorporation attempting to suppress the data; he hires a psychopathic assassin played by Dolph Lundgren to do so. Ice-T and Dina Meyer co-star as Johnny's allies, a freedom fighter and a bodyguard, respectively.

It was shot in Canada; Toronto and Montreal filled in for Newark and Beijing. The project was difficult for Gibson and Longo. After they struggled for years to finance a low-budget adaptation of Gibson's story, Sony greenlit Johnny Mnemonic with a $26 million budget. When Reeves' previous film, Speed, unexpectedly became a major hit, Sony attempted to retool Johnny Mnemonic as a blockbuster. Longo experienced extensive creative differences with the studio, who forced casting choices and script rewrites on him. The film was ultimately recut without Longo's involvement, resulting in a version that he felt did not reflect his artistic vision. Described by Longo and Gibson as originally full of irony, it was edited into a mainstream action film and received negative reviews from critics.

A longer version (103 mins) of the film premiered in Japan on April 15, 1995, featuring a score by Mychael Danna and more scenes involving Kitano. The film was released in the United States on May 26, 1995. In 2022, a black-and-white edition of the film, titled Johnny Mnemonic: In Black and White was released, which Gibson characterized as closer to his original vision.[7]

Plot

[edit]In 2021, society is driven by a virtual Internet, which has created a degenerative effect called "nerve attenuation syndrome" or NAS. Megacorporations control much of the world, intensifying the class hostility already created by NAS.

Johnny is a "mnemonic courier" who discreetly transports sensitive data for corporations in a storage device implanted in his brain at the cost of his childhood memories. His current job is for a group of scientists in Beijing. Johnny initially balks when he learns the data exceeds his memory capacity even with compression, but he agrees given the large fee will cover the cost of the operation to remove the device. Johnny keeps it secret that he is overloaded; he must have the data extracted within a few days or suffer fatal brain damage and corrupt the data. The scientists encrypt the data with three random images from a television feed. As they transmit these images to the receiver in Newark, New Jersey, they are attacked and killed by yakuza led by Shinji, who wields a laser whip. Johnny battles the yakuza, grabs a fragment of the encryption key images, and escapes. Shinji reports his failure to his superior, Takahashi. Their conversation reveals the yakuza are working on behalf of Pharmakom, a megacorporation. Johnny witnesses brief projections of a female artificial intelligence who attempts to aid him, but he dismisses her.

In Newark, Johnny meets with his handler Ralfi, who betrays him. Johnny is rescued from the yakuza by Jane, a cybernetically-enhanced bodyguard; members of the Lo-Teks, an anti-establishment group; and the Lo-Teks' leader, J-Bone. Ralfi is sliced into pieces when he gets in Shinji's way. Jane takes Johnny to Spider, the doctor who installed Jane's implants. At a clinic, Spider reveals his medical charity was intended to receive the Beijing scientists' data, which is a stolen cure for NAS. Spider claims Pharmakom refuses to release the cure because they are profiting off mitigation treatments. The portion of the encryption images Johnny took plus the piece Spider received are insufficient to decrypt Johnny's mind, so Spider suggests they see Jones at the Lo-Teks' base. Suddenly, an assassin hired by Takahashi known as "The Street Preacher" attacks them, killing Spider as Johnny and Jane escape.

The two reach the Lo-Tek base and learn from J-Bone that Jones is a dolphin once used by the Navy that can help decrypt Johnny's payload. As they start the procedure, Shinji and the yakuza attack the base. Takahashi appears and confronts Johnny, holding him at gunpoint, before Shinji, in a surprise betrayal, shoots Takahashi. Johnny and Shinji fight, culminating with Johnny killing Shinji. Before he dies, Takahashi has a change of heart and turns over a portion of the encryption key to Johnny. This still is not enough to fully decrypt the data. J-Bone tells Johnny that he will need to hack his own mind with Jones' help. Johnny, Jane, J-Bone and the Lo-Teks defeat the remaining forces sent after them. The Street Preacher arrives, and, after a fight, is electrocuted to death by Johnny and Jane.

The second attempt starts, and aided by the female AI, Johnny decrypts the data and simultaneously recovers his childhood memories. The AI is revealed to be a virtual version of Johnny's mother, who founded Pharmakom and was angered by the company's actions. As J-Bone transmits the NAS cure information across the internet via pirate broadcasts, Johnny and Jane watch from afar as the Pharmakom headquarters goes up in flames from the public outcry. In celebration, J-Bone disposes of the Street Preacher's burnt corpse by tossing it into the waters of Newark.

Cast

[edit]- Keanu Reeves as Johnny

- Dolph Lundgren as Karl Honig, aka The Street Preacher

- Dina Meyer as Jane

- Ice-T as J-Bone

- Takeshi Kitano as Takahashi

- Denis Akiyama as Shinji

- Henry Rollins as Spider

- Barbara Sukowa as Anna Kalmann

- Udo Kier as Ralfi

- Tracy Tweed as Pretty

- Falconer Abraham as Yomamma

- Don Francks as Hooky

- Diego Chambers as Henson

- Arthur Eng as Viet

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]In the 1980s, director Robert Longo was known primarily for his artwork, including "Men in the Cities", a series of images meant to be viewed sequentially. After having been influenced by film, he transitioned to directing music videos and, when he tired of that, became interested in adapting William Gibson's Johnny Mnemonic.[8] Longo and Gibson first started work on a screenplay in 1989.[9] Longo's first attempt to finance the film was through Warner Bros. in 1990. Bob Krasnow liked Longo's short film, Arena Brains, and offered to finance a feature film. Before pre-production could begin, Warner Bros. merged with Time Inc., and the film was put on hold. Recognizing the film was unlikely to be produced, Krasnow let Longo out of his contract. Longo nearly gave up on getting Johnny Mnemonic made but continued to make contacts in Hollywood.[8]

Longo and Gibson sought to sell Johnny Mnemonic as an art film on a small budget but failed to get financing from the studios.[10] Gibson said they wanted to avoid flashy, MTV-inspired visuals and "plunge the audience into a very strange but consistent universe".[9] Longo commented that the project "started out as an arty 1½-million-dollar movie, and it became a 30-million-dollar movie because we couldn't get a million and a half."[10] Longo's lawyer suggested that their problem was that they were not asking for enough money and that studios would not be interested in such a small project.[11] Studios were also concerned that Longo's artistic background would impact his ability to make a commercially viable film.[12]

The unbounded spread of the Internet in the early 1990s and the consequent rapid growth of high technology culture had made cyberpunk increasingly relevant, and this was a primary motivation for Sony Pictures's decision to fund the project in the tens of millions.[13] Val Kilmer was originally cast in the title role, and Reeves replaced him when Kilmer dropped out.[14] Gibson approved of this casting and said Reeves understood the character well.[9] Reeves' Canadian nationality opened up further financial options, such as Canadian tax incentives.[14] In Canada, Longo discovered he had to maintain Canadian crew quotas. Michael Chapman had agreed to shoot the film, but Longo had to hire a Canadian cinematographer instead.[15]

Pre-production

[edit]When Reeves' previous film, Speed, turned into a major hit in 1994, expectations were raised for Johnny Mnemonic, and Sony saw the film as a potential blockbuster hit.[16] Gibson said Sony executives began pressing them about whether their film had busses or explosions, critical elements of Speed.[17]

Longo's experiences with the financiers were poor, believing that their demands compromised his artistic vision. Many of the casting decisions, such as Lundgren, were forced upon Longo to increase the film's appeal outside of the United States. Longo and Gibson, who had no idea what to do with Lundgren, created a new character for him.[18] Lundgren had previously starred in several action films that emphasized his physique. He intended the role of the street preacher to be a showcase for further range as an actor, but his character's monologue was cut during editing.[19] Gibson said that the monologue, a sermon about transhumanism that Lundgren delivered naked, was cut due to fears of offending religious groups.[20] Kitano was cast to appeal to the Japanese market.[14] Rollins, who is uninterested in science fiction, joined the cast because he liked the film's focus on an upcoming disadvantaged underclass.[12]

The film significantly deviates from the short story, such as turning Johnny, not his bodyguard, into the primary action figure. Molly Millions is replaced with Jane, as the film rights to Molly had already been sold.[21] Gibson did not want Molly in the film, though, and thought it would be best to reserve her for a different franchise.[22] Nerve attenuation syndrome (NAS) is a fictional disease that is not present in the short story. NAS, also called "the black shakes", is caused by an overexposure to electromagnetic radiation from omnipresent technological devices and is presented as a raging epidemic. In the film, one pharmaceutical corporation has found a cure but chooses to withhold it from the public in favor of a more lucrative treatment program.[13][23] References to Jones the dolphin's heroin addiction was one of many plot elements cut during editing.[13]

Filming and post-production

[edit]Shooting took place in Toronto,[12] where Longo temporarily moved his family,[15] and Montreal.[12]

The studio continued to challenge Gibson and Longo on the script through principal photography, making some of the shooting both tense and confusing.[15] The script was meant to be a commentary on science fiction films and how they are made,[24] and the action sequences were meant to be ironic and reminiscent of scenes that Gibson and Longo enjoyed in B movies.[17] Gibson and Longo had instructed Reeves not to play the character straight.[24] For his part, Reeves said he played the character "very robotic and rigid", which he found exhausting.[25] Reeves' suit and tie are a reference to "Men in the Cities".[12] When Johnny cries out for room service, this was a reflection of Longo's frustration,[7] and has also been identified as a reference to "Men in the Cities".[26] The ending, where the Street Preacher appears to revive, was forced on Longo, but he refused to shoot the scene straight, as requested. The studio approved of his version nonetheless.[17] Eight minutes of extra footage starring Kitano was shot for the Japanese release of the film.[14]

Gibson said that the film was "taken away and re-cut by the American distributor" during post-production. He described the original film as "a very funny, very alternative piece of work", and said it was "very unsuccessfully chopped and cut into something more mainstream".[27] Gibson compared this to editing Blue Velvet into a mainstream thriller lacking any irony.[20] Their editor, Ronald Sanders, was replaced by someone that Longo said did not understand the film.[7] Prior to its release, critic Amy Harmon identified the film as an epochal moment when cyberpunk counterculture would enter the mainstream. News of the script's compromises spurred pre-release concerns that the film would prove a disappointment to hardcore cyberpunks.[13] Gibson said he and Longo were in denial at first and believed the film might still be true to their vision. Gibson did not blame anyone for the recut, though, reasoning that the film had been financed with their money.[17] Despite claims made on the internet, the Japanese cut of the film is no closer to a director's cut, and Longo has said that no director's cut exists.[7]

The score was composed by Brad Fiedel. Before Sony's involvement, Black Rain composed a soundtrack. Black Rain had previously provided music for a Gibson audiobook and worked with Longo. Because no shooting had occurred yet, the band composed songs inspired by the original short story. Once Sony became involved, the soundtrack was replaced with Sony artists, such as Stabbing Westward.[28]

Release and marketing

[edit]Simultaneous with Sony Pictures' release of the film, its soundtrack was released by Sony subsidiary Columbia Records, and the corporation's digital effects division Sony ImageWorks issued a CD-ROM videogame version for MS-DOS, Mac, and Windows 3.x.[13] The Johnny Mnemonic videogame, which was developed by Evolutionary Publishing, Inc. and directed by Douglas Gayeton, offered 90 minutes of full motion video storytelling and puzzles.[29] A pinball machine, also titled Johnny Mnemonic, was released.[30]

Sony realized early on the potential for reaching their target demographic through Internet marketing, and its new-technology division promoted the film with an online scavenger hunt offering $20,000 in prizes. One executive was quoted as remarking "We see the Internet as turbo-charged word-of-mouth. Instead of one person telling another person something good is happening, it's one person telling millions!".[13] The film's website, the first official site launched by Columbia TriStar Interactive,[31] facilitated further cross-promotion by selling Sony Signatures-issued Johnny Mnemonic merchandise such as a "hack your own brain" T-shirt and Pharmakom coffee cups. Screenwriter William Gibson was deployed to field questions about the videogame from fans online. Despite having created cyberspace, one of the core metaphors for the internet age, Gibson had never been on the Internet previously. The habitually reclusive novelist likened the experience to "taking a shower with a raincoat on" and "trying to do philosophy in Morse code".[13] Gibson commented that the exercise seemed more like Sony testing the viability of internet marketing rather than an interactive event for their customers.[13]

The film grossed ¥73.6 million ($897,600) in its first 3 days in Japan from 14 screens in the nine key Japanese cities.[32] It was released in the United States and Canada on May 26 in 2,030 theaters, grossing $6 million in the opening weekend. It grossed $19.1 million in total in the United States and Canada against its $26 million budget.[5] Gibson was told that the film performed well in Asia and was one of the few profitable films for Sony in 1995.[17]

Reception

[edit]Rotten Tomatoes, a review aggregator, reports that 20% of 40 surveyed critics gave the film a positive review; the average rating is 4.3/10. The website's consensus reads, "As narratively misguided as it is woefully miscast, Johnny Mnemonic brings the '90s cyberpunk thriller to inane new whoas – er, lows."[33] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 36/100 based on 25 reviews, which the site terms "generally unfavorable reviews".[34] Variety's Todd McCarthy called the film "high-tech trash" and likened it to a video game.[35] Roger Ebert, the film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, gave the film two stars out of four and called it "one of the great goofy gestures of recent cinema".[36] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly rated it C− and called it "a slack and derivative future-shock thriller".[37] Conversely, Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle described it as "inescapably a very cool movie",[38] and Marc Savlov wrote in The Austin Chronicle that the film works well for both Gibson fans and those unfamiliar with his work.[39] Writing in The New York Times, Caryn James called the film "a disaster in every way" and said that despite Gibson's involvement, the film comes off as "a shabby imitation of Blade Runner and Total Recall".[40]

McCarthy said that the film's premise is its "one bit of ingenuity", but the plot, which he called likely to disappoint Gibson's fans, is simply an excuse for "elaborate but undramatic and unexciting computer-graphics special effects".[35] Ebert's review mirrored this view. Sending a courier to physically deliver important information while avoiding enemy agents struck him as "breathtakingly derivative" and illogical outside the artificiality of a film when the internet is available.[36] In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Peter Rainer wrote that the film, when stripped of the cyberpunk atmosphere, is recycled from noir fiction,[41] and LaSalle viewed it more positively as "a hard-boiled action story using technology as its backdrop".[38] Savlov called it "an updated D.O.A.",[39] and Ebert said the film's plot could have worked in any genre and been set in any time period.[36]

James criticized the film's lack of tension,[40] and Rainer called the film's tone too grim and lacking excitement.[41] McCarthy criticized what he saw as a "unrelieved grimness" and "desultory, darkly staged action scenes".[35] McCarthy felt the film's visual depiction of the future was unoriginal,[35] and Gleiberman described the film as "Blade Runner with tackier sets".[37] Savlov wrote that Longo's "attempts to out-Blade Runner Ridley Scott in the decaying cityscape department grow wearisome".[39] Savlov still found the film "much better than expected".[39] LaSalle felt the film "introduces a fantastic yet plausible vision of a computer-dominated age" and maintains a focus on humanity,[38] in contrast to Rainer, who found the film's countercultural pose to be inauthentic and lacking humanity.[41] James called the film murky and colorless;[40] Rainer's review criticized similar issues, finding the film's lack of lighting and its grim set design to give everything an "undifferentiated dullness".[41] McCarthy found the special effects to be "slick and accomplished but unimaginative",[35] though Ebert enjoyed the special effects.[36] Gleiberman highlighted the laser whip as his favorite special effect,[37] though James found it unimpressive.[40]

Although saying that Reeves is not a good actor, LaSalle said Reeves is still enjoyable to watch and makes for a compelling protagonist.[38] McCarthy instead found Reeves' character to be unlikable and one-dimensional.[35] James compared Reeves to a robot,[40] and Gleiberman compared him to an action figure.[37] Rainer posited that Reeves' character may seem so blank due to his memory loss.[41] Savlov said that Reeves' wooden delivery gives the film unintentional humor,[39] but Rainer found that the lack of humor throughout the film sapped all the acting performances of any enjoyment.[41] Gleiberman said that Reeves' efforts to avoid Valleyspeak backfire, giving his character's lines "an intense, misplaced urgency", though he liked the unconventional casting of Lundgren as a psychopathic street preacher.[37] Rainer highlighted Lundgren as the only mirthful actor and said his performance was the best in the film.[41] James called Ice-T's role stereotypical and said he deserved better.[40]

Reeves's performance in the film earned him a Golden Raspberry Award nomination for Worst Actor (also for A Walk in the Clouds), but he lost to Pauly Shore for Jury Duty. The film was filed under the Founders Award (What Were They Thinking and Why?) at the 1995 Stinkers Bad Movie Awards and was also a dishonourable mention for Worst Picture.[42] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "C+" on an A+ to F scale.[43]

Legacy

[edit]In a career retrospective of Reeves' films for Entertainment Weekly, Chris Nashawaty ranked the film as Reeves' second worst, calling the film's fans "nuts" for liking it.[44] While acknowledging the film's issues, critic Ty Burr attributed its poor reviews to critics' unfamiliarity with Gibson's work.[45] The Quietus described the film as having "all the makings of a cult classic",[46] and its release to streaming sites in 2021 resulted in a passionate defense by Rowan Righelato in The Guardian, who said it was "a testament to Longo's genius" that the film remained as eccentric as it was despite the studio's recut.[47] Inverse also recommended the film.[48] In a retrospective review from 2021, Peter Bradshaw, film critic for The Guardian, rated it 4/5 stars and wrote, "Perhaps it's quaint, but it's also watchable, and it is the kind of sci-fi that is genuinely audacious".[49]

The Wachowskis used Johnny Mnemonic as template for describing The Matrix to investors,[50] and the 2011 video game Deus Ex: Human Revolution was influenced by Johnny Mnemonic.[51] The props from the film were transformed into sculptures by artist Dora Budor for her 2015 solo exhibition, Spring.[52]

Johnny Mnemonic: In Black and White

[edit]Sony Pictures Home Entertainment released Johnny Mnemonic: In Black and White on Blu-ray in the United States on August 16, 2022.[53]

A black-and-white version of the theatrical cut, the edition was developed by Robert Longo. While not a director's cut, it is nonetheless closer to Longo's intended vision for the film; he had desired to shoot in black-and-white but was denied the opportunity. Initially, for the film's 25th anniversary, Longo ripped a Blu-ray copy of the film and created a black-and-white version of the film himself. After contacting Don Carmody and informing him of his intention to release the new version of the film on YouTube, Carmody requested to see it first. Impressed, Carmody convinced Longo to approach Sony Pictures for an official release. Sony Pictures agreed to provide the film's footage to Longo for a professional conversion, so that they could release the new version on Blu-ray. Longo proceeded to re-grade the film's color in black-and-white, with the help of the film's original colorist Cyrus Stowe. Longo has stated that he is "happy" with the new version of the film, as he takes inspiration from black-and-white films such as Alphaville and La Jetée. The new version was shown by the Tribeca and Rockaway Film Festivals at an outdoor screening, which sold out, in 2021.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ "Ron Sanders » Directors Guild of Canada". www.dgc.ca. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ a b c d e "Johnny Mnemonic (1995)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on April 17, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "Johnny Mnemonic". Library and Archives Canada. 12 May 2015. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ "JOHNNY MNEMONIC". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on December 22, 2023. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Johnny Mnemonic (1995)". Box Office Mojo (IMDb). Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ "Johnny Mnemonic (1995)". Allmovie. Archived from the original on 2023-07-04. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ a b c d e Dahl, Patrick (10 June 2021). "Johnny Mnemonic in Black-and-White: Robert Longo Interview". Screenslate. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ a b McKenna, Kristine (1992-06-27). "An Artist Is Now a Director : Longo Hopes Crypt Opens Film Career". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2023-04-20. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- ^ a b c Salza, Giuseppe (2014). "William Gibson Interview, Giuseppe Salza / 1994". In Smith, Patrick A. (ed.). Conversations with William Gibson. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-62846-016-2. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ a b van Bakel, Rogier. "Remembering Johnny". Wired. Vol. 3, no. 6. Condé Nast Publications. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ Lewis, Peter H. (May 22, 1995). "ON LINE WITH William Gibson; Present at the Creation, Startled at the Reality". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e McKenna, Kristine (1995-05-21). "It's Just Art on a Big Screen : How did a New York artist land $27 million and star Keanu Reeves to make his very first Hollywood movie? Robert Longo says it's just that he always wanted to direct". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2023-04-16. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harmon, Amy (May 24, 1995). "Crossing Cyberpunk's Threshold: Hollywood: Author William Gibson's dark view of the future hits the mainstream this week in Johnny Mnemonic". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Nashawaty, Chris (June 23, 1995). "Johnny Mnemonic faced financial woes". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Olch, Judith (January 30, 2009). "Oral history interview with Robert Longo". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ Trenholm, Richard (December 22, 2021). "Before The Matrix, Johnny Mnemonic and Hackers led the internet movies of the '90s". CNET. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Diggle, Andy (2014). "William Gibson Interview, Andy Diggle / 1997". In Smith, Patrick A. (ed.). Conversations with William Gibson. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-62846-016-2.

- ^ Riefe, Jordan (May 18, 2016). "Director Robert Longo Ruefully Recalls Johnny Mnemonic: 'I Had Post-Traumatic Stress From That Movie'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Pinsker, Beth (June 16, 1995). "Dolph Lundgren wants to show he's a serious actor". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Henthorne, Tom (15 June 2011). William Gibson: A Literary Companion. McFarland & Company. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-7864-6151-6.

- ^ Dillard, Brian J. "Johnny Mnemonic > Review". Allmovie (All Media Guide). Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ "Alexandra DuPont Interviews William 'Freakin' Gibson!!!!". Ain't It Cool News. February 3, 2000. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ Kehe, Jason (January 11, 2021). "2021 and the Conspiracies of Johnny Mnemonic". Wired. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Walsh, Joseph (December 3, 2014). "William Gibson Talks Cyberpunk, Cyberspace, and His Experiences in Hollywood". Vice. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ McKenna, Kristine (1994-06-05). "Movies : Keanu's Eccentric Adventure : From stoner dude to computer brain, 29-year-old Keanu Reeves has racked up 16 films during his eight hard-working years of acting, and emerged almost untarnished by the corrosive glitter of Hollywood". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2023-04-17. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- ^ Auger, Emily E. (2011). Tech-noir Film: A Theory of the Development of Popular Genres. Intellect Books. p. 336. ISBN 978-1-84150-424-7.

- ^ Lincoln, Ben (October 19, 1998). "Arts: Cyberpunk on screen - William Gibson speaks". The Peak. 100 (7). Archived from the original on June 27, 2007.

- ^ Sherburne, Philip (2012-04-19). "Lost Johnny Mnemonic Soundtrack Unearthed!". Spin. Archived from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (June 2, 1995). "Johnny Mnemonic". Entertainment Weekly. Time Warner. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ McNamara, Chris (2005-11-27). "Pinball's still in play". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2023-04-15. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ Graser, Marc (January 25, 1999). "Col caught in Web". Variety (Columbia Pictures 75th Anniversary ed.). p. 76.

- ^ Groves, Don (April 24, 1995). "'Mnemonic' bows big in Japan". Variety. p. 12. Archived from the original on May 31, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "Johnny Mnemonic Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes (Flixster). Archived from the original on August 30, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ "Johnny Mnemonic". Metacritic. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f McCarthy, Todd (May 22, 1995). "Johnny Mnemonic". Variety. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Ebert, Roger (May 26, 1995). "Johnny Mnemonic". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Gleiberman, Owen (June 9, 1995). "Johnny Mnemonic". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d LaSalle, Mick (May 27, 1995). "'Mnemonic' Has a Cool Head / Keanu Reeves in futuristic computer age". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Savlov, Marc (June 2, 1995). "Johnny Mnemonic". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f James, Caryn (May 26, 1995). "FILM REVIEW; Too Much on His Mind, Ready to Go BLOOEY". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rainer, Peter (May 26, 1995). "MOVIE REVIEW : A Head Case Named 'Johnny Mnemonic'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "1995 18th Hastings Bad Cinema Society Stinkers Awards". The Envelope. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2007.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved 2023-10-07.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (March 31, 2019). "Keanu Reeves' best and worst movies, ranked". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Burr, Ty (November 17, 1995). "Johnny Mnemonic". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Robb, David (December 21, 2021). "Hack The Matrix: How Johnny Mnemonic Predicted 2021". The Quietus. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Righelato, Rowan (30 April 2021). "Hear me out: why Johnny Mnemonic isn't a bad movie". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Newby, Richard (May 11, 2021). "You Need to Watch the Weirdest Cyberpunk Movie". Inverse. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (May 6, 2021). "Johnny Mnemonic review – Keanu test-drives early Matrix prototype". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Hemon, Aleksandar (September 3, 2012). "Beyond the Matrix". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Walker, John (June 14, 2011). "Square Enix Talk Deus Ex: Human Revolution". Rock Paper Shotgun. Archived from the original on May 31, 2023. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ "Dora Budor "Spring" at Swiss Institute, New York" (PDF). Mousse Magazine. July 8, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Chabot, Jeff (30 July 2022). "Johnny Mnemonic starring Keanu Reeves releasing in Black & White on Blu-ray". HD Report. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

External links

[edit]- 1995 films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s Canadian films

- 1990s dystopian films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s Japanese-language films

- 1990s science fiction action films

- 1995 directorial debut films

- 1995 science fiction films

- Alliance Films films

- American chase films

- American dystopian films

- American science fiction action films

- Canadian science fiction action films

- Fiction about cryptography

- Cyberpunk films

- Fiction about corporate warfare

- Films about artificial intelligence

- Films about computing

- Films about dolphins

- Films about telepresence

- Films based on Canadian short stories

- Films based on science fiction works

- Films produced by Don Carmody

- Films scored by Brad Fiedel

- Films scored by Mychael Danna

- Films set in 2021

- Films set in Beijing

- Films set in New Jersey

- Films shot in Montreal

- Films shot in Toronto

- Transhumanism in film

- TriStar Pictures films

- Works by William Gibson

- Stinkers Bad Movie Award winning films

- English-language science fiction action films