EarthBound

| EarthBound | |

|---|---|

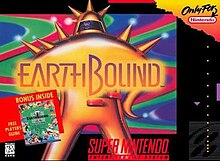

North American box art by Mike Tagaki, depicting a Final Starman with Ness' reflection in its visor | |

| Developer(s) | Ape Inc. HAL Laboratory[nb 1] |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | Shigesato Itoi |

| Producer(s) | Shigesato Itoi Satoru Iwata Tsunekazu Ishihara |

| Designer(s) | Akihiko Miura |

| Programmer(s) | Satoru Iwata Kouji Malta |

| Artist(s) | Kouichi Ooyama |

| Writer(s) | Shigesato Itoi |

| Composer(s) | Keiichi Suzuki Hirokazu Tanaka |

| Series | Mother |

| Platform(s) | Super NES Game Boy Advance |

| Release | Mother 1+2

|

| Genre(s) | Role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

EarthBound, released in Japan as Mother 2: Gīgu no Gyakushū,[nb 2][1][2] is a 1994 role-playing video game developed by Ape Inc. and HAL Laboratory and published by Nintendo for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System as the second entry in the Mother series. The game focuses on Ness and his party of Paula, Jeff and Poo, as they travel the world to collect melodies from eight Sanctuaries in order to defeat the universal cosmic destroyer Giygas.

EarthBound had a lengthy development period that spanned five years. Its returning staff from Mother (1989) included writer/director Shigesato Itoi and lead programmer Satoru Iwata, as well as composers Keiichi Suzuki and Hirokazu Tanaka, who incorporated a diverse range of styles into the soundtrack, including salsa, reggae, and dub. Most of the other staff members had not worked on the original Mother, and the game came under repeated threats of cancellation until Iwata joined the team. Originally scheduled for release in January 1993, the game was completed around May 1994 and first released in Japan in August 1994, and in North America in June 1995. A port for the Game Boy Advance developed by Pax Softnica, bundled with Mother, as Mother 1+2, was released only in Japan in 2003.[3]

Like its predecessor, EarthBound is themed around an idiosyncratic portrayal of Americana and Western culture, subverting popular role-playing game traditions by featuring a modern setting while parodying numerous staples of the genre. Itoi wanted the game to reach non-gamers with its intentionally goofy tone; for example, the player uses items such as the Pencil Eraser to remove pencil statues, experiences in-game hallucinations, and battles piles of vomit, taxi cabs, and walking nooses. For its American release, the game was marketed with a $2 million promotional campaign that sardonically proclaimed "This game stinks". The game's puns and humor were reworked by localizer Marcus Lindblom. Since the original Mother had not yet been released outside Japan, Mother 2 was called EarthBound to avoid confusion about what it was a sequel to.

Although it was positively received by Japanese audiences, EarthBound sold poorly in the United States, which journalists attributed to a combination of its simple graphics, satirical marketing campaign, and a lack of market interest in the genre. In the ensuing years, a dedicated fan community spawned that advocated for the series' recognition, particularly after Ness appeared as a playable character in the Super Smash Bros. series. By the 2000s, multiple reader polls and critics had named it one of the greatest video games ever made, and it became regarded as a "sacred cow among gaming's cognoscenti".[4] It was followed by the Japan-only sequel Mother 3 for the Game Boy Advance in 2006. EarthBound was later made available worldwide on the Wii U Virtual Console in 2013, 3DS Virtual Console in 2016, the SNES Classic in 2017, and Nintendo Switch Online in February 2022.

Gameplay

[edit]

EarthBound features many traditional role-playing game elements: the player controls a party of characters who travel through the game's two-dimensional world composed of villages, cities, caves, and dungeons. Along the way, the player fights battles against enemies and the party receives experience points for victories.[5] If enough experience points are acquired, a character's level will increase. This pseudo-randomly increases the character's attributes, such as offense, defense, and the maximum hit points (HP) and psychic points (PP) of each character. Rather than using an overworld map screen like most console RPGs of its era, the world is entirely seamless, with no differentiation between towns and the outside world.[6] Another non-traditional element is the perspective used for the world. The game uses oblique projection, while most 2D RPGs use a "top-down" view on a grid or an isometric perspective.[7]

Unlike its predecessor, Mother, EarthBound does not use random encounters. In EarthBound, enemies are presented similar to other non-player characters scattered around the game's overworld. While the player can see enemy parties on-screen, the composition of the parties are randomly generated. If the player touches an enemy from the front or side while facing forward or sideways, the battle mode starts normally with no special advantage gained. Successfully approaching an enemy from behind allows the player and their party to make a free opening attack against the enemy before normal combat begins. If the enemy attacks from behind the player, the enemy makes a free opening attack that the player can dodge. In combat, once an enemy or character's HP reaches zero, that enemy or character is rendered unconscious. There is a chance that the party will receive an item after the battle. Battle commands include attacking, spying (reveals enemy weakness), mirroring (emulates an enemy), and running away. Characters can also use PSI actions that require PP. Once each character is assigned a command, the characters and enemies perform their actions in an order determined by character speed and a random number generator. Whenever a character receives damage, the HP box gradually "rolls" down, similar to a mechanical counter. This allows players an opportunity to heal the character or win the battle before the counter hits zero, saving the character from being rendered unconscious.[nb 3] This mechanic does not apply to enemies, for whom unconsciousness is instantaneous and can be reversed only with healing PSI. If all characters are rendered unconscious, the game transitions to an endgame screen, asking if the player wants to continue. An affirmative response brings Ness, conscious, back to the last save point, with half the money on his person at the time of his defeat, and with other party members still unconscious. If the party contacts an enemy from behind (indicated by a translucent green swirl that fills the screen), the player is given a first-strike priority when battle mode begins. If the party contacts an enemy with their backs, the swirl is red, and the enemy is given first-strike priority. Neutral priority is indicated by a black swirl. Battles with weaker enemies are won automatically, forgoing the battle sequence, and weaker monsters will flee from Ness and his friends rather than chase them.[5]

Currency is indirectly received from battles. Each time the party wins a battle, Ness's father, who can also save the game's progress, deposits money in an account that can be withdrawn at ATMs. In towns, players can buy weapons, armor, and items from stores. Weapons and armor can be equipped to increase character strength and defense, respectively. Items can be used for a number of purposes, such as healing. Towns also contain useful facilities such as hospitals where players can be healed for a fee.[8]

Plot

[edit]EarthBound takes place sometime in the 1990s,[nb 4] several years after the events of Mother, in the fictional country of Eagleland, a parody of the United States. A young boy named Ness[nb 5] is awoken by a nearby meteorite crash[10] and investigates it with his neighbor, Pokey Minch,[11][nb 6] to find Pokey's missing brother, Picky. When Ness and Pokey arrive at the meteor, it opens up and a small, beetle-like creature from the future named Buzz-Buzz emerges from it. He explains that in the future, an alien force named Giygas has enveloped and consumed the world in hatred and consequently turned animals, humans, and objects into malicious creatures. Buzz-Buzz instructs Ness to collect melodies in a Sound Stone from eight Sanctuaries to preemptively stop the force,[12] but is killed shortly thereafter when Pokey and Picky's mother mistakes him for a pest. On his journey to visit the sanctuaries, Ness visits the cultists of Happy Happy Village, where he saves a young girl named Paula, and the zombie-infested Threed, where the two of them fall prey to a trap. After Paula telepathically instructs precocious child scientist Jeff in a Winters boarding school to rescue them, they continue to Saturn Valley, a village filled with a species of creatures called Mr. Saturn, the city of Fourside, and the seaside resort Summers. Meanwhile, Poo, the prince of Dalaam, undergoes "Mu Training" before joining the party as well.[11]

The party continues to travel to the Scaraba desert, the Deep Darkness swamp, another village of creatures called the Tenda and a forgotten underworld where dinosaurs live. When the Sound Stone is eventually filled,[13] Ness visits Magicant, a surreal location in his mind where he fights his personal dark side.[11] Upon returning to Eagleland, Ness and his party use the Phase Distorter to travel back in time to fight Giygas, transferring their souls into robots so as to not destroy their bodies through time travel. The group discovers a device that contains Giygas, but it is being guarded by Pokey, who has been aiding Giygas all along and is using alien technology. After being defeated in battle, Pokey turns the device off, releasing Giygas and forcing the group to fight[14] the alien, whose infinite power transformed him into an incomprehensible embodiment of evil and insanity. During the fight, Paula reaches out to the inhabitants of Earth, and eventually the player, who prays for the children's safety. The prayers manage to exploit Giygas' fatal weakness – human emotions – and defeat the alien, eradicating him from existence.[11] In a post-credits scene, Ness, whose life has returned to normal following Giygas' defeat, receives a note from Pokey, who challenges Ness to come and find him.[12]

Development

[edit]The first Mother was released for the NES in 1989.[15] Its sequel, Mother 2, or EarthBound, was developed over five years[6] by Ape and HAL, and published through Nintendo.[16] The game was written and designed by Japanese author, musician, and advertiser Shigesato Itoi,[17] and produced by Satoru Iwata, who became Nintendo's president and CEO.[18] Mother 2 was made with a development team different from that of the original game,[19] and most of its members were unmarried and willing to work all night on the project.[20] Mother 2's development took much longer than planned and came under repeated threats of cancellation.[6] Itoi has said that the project's dire straits were resolved when Iwata joined the team.[19] Ape's programming team had more members than HAL on the project. The HAL team (led by lead programmer Iwata) worked on the game programming, while the Ape team (led by lead programmer Kouji Malta) worked on specific data, such as the text and maps. They spent biweekly retreats together at the HAL office in view of Mount Fuji.[21]

The game continues Mother's story in that Giygas reappears as the antagonist (and thus did not die at the end of Mother) and the player has the option of choosing whether to continue the protagonist's story by choosing whether to name their player-character the same as the original.[22] He considered interstellar and interplanetary space travel instead of the confines of a single planet in the new game. After four months, Itoi scrapped the idea as cliché. Itoi sought to make a game that would appeal to populations that were playing games less, such as girls.[6]

The Mother series titles are built on what Itoi considered "reckless wildness", where he would offer ideas that encouraged his staff to contribute new ways of portraying scenes in the video game medium.[12] He saw the titles foremost as games and not "big scenario scripts".[12] Itoi has said that he wanted the player to feel emotions such as "distraught" when playing the game.[12] The game's writing was intentionally "quirky and goofy" in character,[15] and written in the Japanese kana script so as to give dialogue a conversational feel. Itoi thought of the default player-character names when he did not like his team's suggestions. Many of the characters were based on real-life personalities. For instance, the desert miners were modeled on specific executives from a Japanese construction company.[6] The final battle dialogue with Giygas was based on Itoi's recollections of a traumatic scene from the Shintoho film The Military Policeman and the Dismembered Beauty that he had accidentally seen in his childhood.[23] Itoi referred to the battle background animations as a "video drug".[6] The same specialist made nearly 200 of these animations, working solely on backgrounds for two years.[6]

The idea for the rolling HP meter began with pachinko balls that would drop balls off the screen upon being hit. This did not work as well for characters with high health. Instead, around 1990, they chose an odometer-style hit points counter.[6] The bicycle was one of the harder elements to implement[21]—it used controls similar to a tank before it was tweaked.[6] Iwata felt that the Ape programmers were particularly willing to tackle such challenges. The programmers also found difficulty implementing the in-game delivery service, where the delivery person had to navigate around obstacles to reach the player. They thought it would be funny to have the delivery person run through obstacles in a hurry on his way off-screen.[21] The unusual maps laid out with diagonal streets in oblique projection required extra attention from the artists. Itoi specifically chose against having an overworld map, and didn't want to artificially distinguish between towns and other areas. Instead, he worked to make each town unique. His own favorite town was Threed, though it was Summers before then.[6]

Mother 2 was designed to fit within an eight-megabit limit, but was expanded in size and scope twice: first to 12 megabits and second to 24 megabits.[6] The game was originally scheduled for release in January 1993 on a 12 megabit cartridge.[24] It was finished around May 1994[21] and the Japanese release was set for August 27.[25] With the extra few months, the team played the game and added small, personal touches.[21] Itoi told Weekly Famitsu that Shigeru Miyamoto liked the game and that it was the first role-playing game that Miyamoto had completed.[6] Mother 2 would release in North America about a year later.[26]

The game includes anti-piracy measures that, when triggered, increases enemy counts to make the game less enjoyable. Additionally, right before players reach the end of the pirated copy's story, their game resets and deletes its saved file in an act that IGN declared "arguably the most devious and notorious example of 'creative' copy protection".[27]

Music

[edit]Mother composers Keiichi Suzuki and Hirokazu Tanaka returned to make the EarthBound soundtrack, along with newcomers Hiroshi Kanazu and Toshiyuki Ueno.[28][29] In comparison with Mother, Itoi said that EarthBound had more "jazzy" pieces.[6] Suzuki told Weekly Famitsu that the Super NES afforded the team more creative freedom with its eight-channel ADPCM based SPC700, as opposed to the old Nintendo Entertainment System's restriction of five channels of basic waveforms. This entailed higher sound quality and music that sounds closer to his regular compositions.[30] The soundtrack was released by Sony Records on November 2, 1994.[29][nb 7]

In Suzuki's songwriting process, he would first compose on a synthesizer before working with programmers to get it in the game. His personal pieces play when the player is walking about the map, out of battle. Suzuki's favorite piece is the music that plays while the player is on a bicycle, which he composed in advance of this job but found appropriate to include. He wrote over 100 pieces, but much of it was not included in the game.[30] The team wrote enough music as to fill eight megabits of the 24 megabit cartridge—about two compact discs.[6]

According to Tanaka, the Beach Boys were repeatedly referenced between him and Suzuki, and that he would often listen to co-founder Brian Wilson's 1988 eponymous album while on the way to Suzuki's home.[31] Suzuki has stated that the percussive arranging in the game's soundtrack was based on the Beach Boys' albums Smile (unreleased) and Smiley Smile (1967), which both contained American themes shared with Van Dyke Parks' Song Cycle (1968). To Suzuki, Smile evoked the bright and dark aspects of America, while Song Cycle displayed a hazy sound mixed with American humor and hints of Ray Bradbury, a style that he considered essential to the soundtrack of Mother.[31][nb 8] Tanaka recalls Randy Newman being the first quintessentially American composer he could think of, and that his albums Little Criminals (1977) and Land of Dreams (1988) were influential.[31] While Suzuki corroborated with his own affinity for Harry Nilsson's Nilsson Sings Newman (1970),[31] he also cited John Lennon as a strong influence due to the common theme of love in his music, which was also a prominent theme in the game,[30] and that his album John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band (1970) helped him to avoid excessive instrumentation over the SNES's technical constraints.[31]

The soundtrack contains direct musical quotations of some classical and folk music; the composers also derived a few samples culled from other sources including commercial pop and rock music.[15][nb 9] The texture of the work was partially influenced by some salsa, reggae, and dub music.[31][nb 10] Speaking about Frank Zappa's Make a Jazz Noise Here (1991), Tanaka felt that Zappa would have been the best at creating a live performance of Mother music, but could not detail Zappa's specific influence on EarthBound. Additionally, he felt that the mix tape Wired Magazine Presents: Music Futurists (1999) presented a particular selection of artists that embody the ethos of EarthBound, running the gamut from space age composer Esquivel to avant-garde trumpeter Ben Neill, along with innovators Sun Ra, Steve Reich, Todd Rundgren, Brian Eno, and Can.[31][nb 11] Tanaka also mentioned that he listened to the various artists compilation Stay Awake: Various Interpretations of Music from Vintage Disney Films (1988) heavily during EarthBound's development.[31] Miscellaneous influences on Suzuki and Tanaka for EarthBound include the music of Michael Nyman, Miklós Rózsa's film score for The Lost Weekend (1945), and albums by various other pop/rock musicians.[31][nb 12]

English localization

[edit]As was traditional for Nintendo, Mother 2 was developed in Japan and localized in the United States, a process in which the game is translated into English for Western audiences.[15] As it was the only game in the Mother series to be released in North America at the time,[16] its title "Mother 2" was changed to "EarthBound" to avoid confusion about what it was a sequel to.[15]

Nintendo of America's Dan Owsen began the English localization project and converted about ten percent of the script before moving to another project.[15] Marcus Lindblom filled Owsen's position around January 1995.[35] Lindblom credits Owsen with coining some of the game's "most iconic phrases", such as "say fuzzy pickles".[15] Lindblom himself was given liberties to make the script "as weird as [he] wanted", as Nintendo wanted the script to be more American than a direct translation would be.[35] He worked alone and with great latitude due to no divisional hierarchies.[18][nb 13] Lindblom was aided by Japanese writer Masayuki Miura, who translated the Japanese script and contextualized its tone,[15] which Lindblom positively described as "a glass half full".[35]

Lindblom was challenged by the task of culturally translating "an outsider's view of the U.S." for an American audience.[35] He also sought to stay true to the original text, though he never met or spoke with Itoi.[35] In addition to reworking the original puns and humor, Lindblom added private jokes and American cultural allusions to Bugs Bunny, comedian Benny Hill, and This Is Spinal Tap.[35] Apart from the dialogue, he wrote the rest of the game's text, including combat, prompts and item names.[15] As one of several Easter eggs, he named a non-player character for his daughter, Nico, who was born during development. While Lindblom took the day off for her birth,[35] he proceeded to work 14-hour days[15] without weekends for the next month.[35]

Under directives from Nintendo,[35] Lindblom worked with the Japanese artists and programmers[15] to remove references to intellectual property, religion, and alcohol from the American release, such as a truck's Coca-Cola logo, the red crosses on hospitals, and crosses on tombstones.[35] Alcohol became coffee or cappuccinos, Ness was no longer nude in the Magicant area as seen in the image,[15] and the Happy Happyist blue cultists were made to look less like Ku Klux Klansmen.[35] The team was not concerned with music licensing issues and considered itself somewhat protected under the guise of parody.[15] Lindblom recalled that the music did not need many changes. The graphical fixes were not finished until March 1995, and the game was not fully playable until May.[35]

Reception

[edit]Sales and promotion

[edit]In Japan, Mother 2 sold 518,000 units, becoming the tenth best-selling game of 1994 within the country.[36] EarthBound was released on June 5, 1995, in North America.[35] The game sold about 140,000 units in the United States,[37] for a total of approximately 658,000 units sold worldwide.

Though Nintendo spent about $2 million on marketing,[17] the American release was ultimately viewed as unsuccessful within Nintendo.[35] The game's atypical marketing campaign was derived from the game's unusual humor. As part of Nintendo's larger "Play It Loud!" campaign, EarthBound's "this game stinks" campaign included foul-smelling scratch and sniff advertisements.[26][42] GamePro reported that they received more reader complaints about the game's scratch and sniff ad than about any other 1995 advertisement.[43] The campaign was also expensive. It emphasized magazine advertisements and had the extra cost of the strategy guide included with each game.[44] Between the poor sales and the phasing out of the Super NES, the game did not receive a European release.[17] Aaron Linde of Shacknews believed that the price of the packaged game ultimately curtailed sales.[26]

Contemporary

[edit]| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Famitsu | 34/40[45] |

| Game Informer | 8/10[47] |

| GameFan | 267/300[46] |

| Super Game Power | 3.5/5[48] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| GameFan Megawards | RPG of the Year[49] |

EarthBound originally received little critical praise from the American press,[15][44] and sold poorly in the US:[16][35][44] around 140,000 copies, as compared to twice as many in Japan.[26] Kotaku described EarthBound's 1995 American release as "a dud" and blamed the low sales on "a bizarre marketing campaign" and graphics "cartoonish" beyond the average taste of players.[15] The game was released when RPGs were not popular in the US,[35][50] and visual taste in RPGs was closer to Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy VI.[35] The game piggybacked on Itoi's celebrity in Japan.[17]

Most journalists attributed the game's poor sales in the US to its simple graphics, atypical marketing campaign, and disinterest in the genre. Of the original reviewers, Nicholas Dean Des Barres of DieHard GameFan wrote that EarthBound was not as impressive as Final Fantasy III, although just as fun.[51] He praised the game's humor[46] and wrote that the game completely defied his first impressions. Des Barres wrote that "past the graphics", which were purposefully 8-bit for nostalgia, the game is not an "entry-level" or a "child's" RPG, but "highly intelligent" and "captivating".[51] The Brazilian Super GamePower explained that those expecting a Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG will be disappointed by the childish visuals, which were unlike other 16-bit games. They wrote that the American humor was too mature and that the gameplay was too immature, as if for beginners.[48] GamePro was critical to the game's storyline and graphics, but praised the music and the humor. They concluded that the game is inappropriate for children due to its adult humor, but would not appeal to more mature gamers due to its simplistic gameplay and poorly illustrated graphics.[52]

Lindblom and his team were devastated by the release's poor critical response and sales. He recalled that the game was hurt by the reception of its graphics as "simplistic" at a time when critics placed high importance on graphics quality.[nb 14] Lindblom felt that the game's changes to the RPG formula (e.g., the rolling HP meter and fleeing enemies) were ignored in the following years,[15] though he thought the game had aged well at the time of its Virtual Console rerelease in 2013.[35]

Retrospective

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| GameRankings | 88%[53] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | 4/5[54] |

| GameZone | 10/10[10] |

| IGN | 9.0/10[55] |

| Nintendo Life | 10/10[57] |

| Nintendo World Report | 9.5/10[56] |

| Official Nintendo Magazine | 90%[17] |

Reviewing the game years after its release, writers described the game as "original" or "unique",[17][55] and praised its script's range of emotions.[17][55] IGN's Scott Thompson said the game teetered between solemn and audacious in its dialogue and gameplay, and noted its deviance from RPG tropes in aspects such as choice of attacks in battle. He found the game both "bizarre and memorable".[55] Official Nintendo Magazine's Simon Parkin thought the game's script was its best asset, as "one of the medium's strongest and idiosyncratic storylines" that fluctuated "between humorous and poignant".[17] GameZone's David Sanchez thought its script was "clever" and "sharp", as it displayed a wide range of emotions that made him want to talk to all non-player characters.[10] GamesTM wrote that the game designers spoke with their players through the non-playable characters, and noted how Itoi's interests shaped the script, its allusions to popular culture, and its "strangely existential narrative framework".[58] Nintendo Life praised the game's touching story, charm and modern-day setting, with minor criticism of the slow pacing.

Critics praised its "real world" setting, which was seen as an uncommon choice.[17][55] Thompson noted its 1990s homage as "a love letter to 20th-century Americana", with a payphone as a save point, ATMs to transfer money, yo-yos as weapons, skateboarders and hippies as enemies, and references to classic rock bands.[55] Official Nintendo Magazine's Parkin noted the theme's distance from the "knights and dragons" common to the Japanese role-playing game genre.[17] Thompson noted the game's steep difficulty. He wrote that the beginning was the hardest and that aspects such as limited inventory, experience grinds, and monetary penalties upon death were unfriendly for players new to Japanese RPGs. He also cited the quick respawn time for foes and ultimate need not to avoid battles given the difficulty of bosses.[55]

Reviewers described the game's ambiance as cheery and full of charm.[10][55] David Sanchez of GameZone thought the game's self-awareness added to its charm, where the player learned through the game's poking lighthearted fun. He added that the music was an "absolute delight" and complimented its range from space sounds to themes to "bizarre" battle tracks that varied with the enemy type.[10] GamesTM wrote that the game's reputation comes from the "consistent ... visual language" in its Charles M. Schulz-esque character and world design.[58] Kotaku's Jason Schreier found the ending unsatisfying and unrelieving, despite finding the ending credits with its character curtain call and photo album of "fuzzy pickles" moments all "wonderful".[12]

Thompson wrote that EarthBound balances "dark Lovecraftian apocalypse and silly lightheartedness", and was just as interesting nearly a decade after its original release. While he lamented a lack of "visual feedback" in battle animations, he felt the game had innovations that still feel "smart and unique": the rolling HP meter and lack of random battles. Thompson also noted that technical issues like animation slowdown with multiple enemies on-screen went unfixed in the rerelease.[55] Parkin found the game to provide a more potent experience than developers with more resources and thought its battle sequences were "sleek".[17] Nintendo World Report's Justin Baker was surprised by the "excellent" battle system and controls, which he found to be underreported in other reviews despite their streamlined, grind-reducing convenience. He wrote that some of the menu interactions were clunky.[56] GamesTM felt that the game was "far from revolutionary", compared to Final Fantasy VI and Chrono Trigger, and that its battle scenes were unexciting. The magazine compared the game's "chosen one" story to a "throwaway Link's Awakening/Goonies hybrid narrative".[58] Thompson praised Nintendo for digitizing the Player's Guide, though noted that it was technically easier to view it on another tablet rather than switching the Wii U's view mode.[55] Reviewers concluded that the game had aged well.[9][10][17][55][56]

Legacy

[edit]Acclaim and influence

[edit]EarthBound was listed in 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die, where Christian Donlan wrote that the game is "name-checked by the video gaming cognoscenti more often than it's actually been played". He called the game "utterly brilliant" and praised its overworld and battle system.[59] Similarly, Eurogamer's Simon Parkin described it as a "sacred cow amongst gaming's cognoscenti".[4] Game journalists have ranked EarthBound among the best Super NES games[16] and most essential Japanese role-playing games,[60][61] and at least three reader polls ranked the game among the best of all time.[62][63][64] For a piece about the "top worlds" in video games, IGN rated EarthBound's setting among the best, indelible between its unconventional environments, 1960s music, and portrayal of Americanism.[65]

Kotaku described the game "as one of the weirdest, most surreal role-playing games in RPG history".[12] Examples include using items such as the Pencil Eraser to remove pencil statues, experiencing in-game hallucinations, meeting "a man who turned himself into a dungeon", and battling piles of vomit,[12] taxi cabs, and walking nooses.[66] David Sanchez of GameZone wrote that EarthBound "went places no other game would" in the 1990s or even in the present day, including "trolling" the player "before trolling was cool".[10] Localization reviewer Clyde Mandelin described the Japanese-to-English conversion as "top-notch for its time".[15] 1UP.com said it was "unusually excellent" for the time.[50] IGN wrote that Nintendo was "dead wrong" for believing that Americans would not be interested in "such a chaotic and satirical world".[65] Complex included EarthBound as one of the "Best Super Nintendo Games of All Time", saying the game is "definitely the craziest and one of the most fun RPGs the SNES had to offer.[67]

Jeremy Parish of USgamer called EarthBound "the all-time champion" of self-aware games that "warp ... perceptions and boundaries" and break the fourth wall, citing its frequent internal commentary about the medium and the final scenes where the player is directly addressed by the game.[68][nb 15] GamesTM said the game felt fresh because of its reliance on "personal experiences" made it "exactly the sort of title that would thrive today as an indie hit".[58] He called this accomplishment "remarkable" and credited Nintendo's commitment to the "voices of creators".[58] IGN's Nadia Oxford said that nearly two decades since the release, its final boss fight against Giygas continues to be "one of the most epic video game standoffs of all time" and noted its emotional impact.[11] Kotaku wrote that the game was content to make the player "feel lonely", and, overall, was special not for any individual aspect but for its method of using the video game medium to explore ideas impossible to explore in media.[12]

The few role-playing games set in real-world settings, PC Gamer has written, are often and accurately described as having been influenced by EarthBound.[69] It was cited as an influence on video games including Costume Quest;[70][71] South Park: The Stick of Truth (via South Park creator Trey Parker);[72][73] Undertale;[74][75] Contact;[68][76] Omori;[77] Lisa;[78] Citizens of Earth;[79] YIIK: A Postmodern RPG;[80][69] the webcomic Homestuck;[81] and Kyoto Wild.[82] Japanese writer Hiromi Kawakami told Itoi that she had played EarthBound "about 80 times".[19]

Fandom

[edit]A cult following for EarthBound developed after the game's release.[35][75] Colin Campbell of Polygon wrote that "few gaming communities are as passionate and active" as EarthBound's,[18] and 1UP.com's Bob Mackey wrote that no game was as poised to have a cult following.[50] IGN's Lucas M. Thomas wrote in 2006 that EarthBound's "persistent", "ambitious", and "religiously dedicated collective of hardcore fans" would be among the first groups to influence Nintendo's decision-making through their purchasing power on Virtual Console.[66] Digital Trends's Anthony John Agnello wrote that "no video game fans have suffered as much as EarthBound fans", and cited Nintendo's reluctance to release Mother series games in North America.[41] IGN described the series as neglected by Nintendo in North America for similar reasons.[66] Nintendo president Satoru Iwata later credited the community response on their online Miiverse social platform as leading to EarthBound's eventual rerelease on their Virtual Console platform.[83] Physical copies of EarthBound were hard to find before the rerelease,[12] and in 2013, were worth twice its initial retail price.[35]

Wired described the amount of EarthBound "fan art, videos, and tributes on fan sites like EarthBound Central or Starmen.net" as mountainous.[35] Reid Young of Starmen.net and Fangamer credits EarthBound's popularity to its "labor of love" nature, with a "double-coat of thoughtfulness and care" across all aspects of the game by a development team that appeared to love their work.[50] Young started the fansite that would become Starmen.net in 1997 while in middle school. It became "the definitive fan community for EarthBound on the web" and had "almost inexplicable" growth.[50] Shacknews described the site's collection of fan-made media as "absolutely massive".[26] It also provided a place to aggregate information on the Mother series and to coordinate fan actions.[26]

The EarthBound fan community at Starmen.net coalesced with the intent to have Nintendo of America acknowledge the Mother series.[50] The community drafted several thousand-person petitions for specific English-language Mother series releases,[26] but in time, their request shifted to no demand at all, wanting only their interest to be recognized by Nintendo.[84] A 2007 campaign for a Mother 3 English localization led to the creation of a full-color, 270-page art book—The EarthBound Anthology—sent to Nintendo and press outlets as demonstration of consumer interest.[85] Shacknews called it more of a proposal than a collection of fan art, and "the greatest gaming love letter ever created".[26] Upon "little" response from Nintendo, they decided to localize the game themselves.[85] Starmen.net co-founder and professional game translator Clyde "Tomato" Mandelin led the project from its November 2006 announcement[26] to October 2008 finish.[86] They then printed a "professional quality strategy guide" through Fangamer, a video game merchandising site that spun off from Starmen.net.[85] Unlicensed EarthBound-themed merchandise produced by Fangamer contributors included T-shirts, a pin set and a mug;[87] The Verge cited the effort as proof of the fan base's dedication.[88]

Other fan efforts include EarthBound, USA, a full-length documentary on Starmen.net and the fan community,[89] and Mother 4, a fan-produced sequel to the Mother series that went into production when Itoi definitively "declared" that he was done with the series.[90] After following the fan community from afar, Lindblom came out to fans in mid-2012 and the press became interested in his work. He had planned a book about the game's development, release, and fandom before a reply from Nintendo discouraged him from pursuing the idea. He plans to continue to communicate directly with the community about the game's history.[18][nb 16] Books that have been written about EarthBound include Ken Baumann's Earthbound, by Boss Fight Books,[92] and Legends of Localization Book 2: Earthbound, by Clyde Mandelin.[93]

Ness

[edit]A variety of merchandise depicting Ness have been produced by Nintendo; this merchandise includes a figurine[94] and an Amiibo.[95] Ness became widely known for his appearance as a playable character throughout the Super Smash Bros. fighting game series,[16] debuting as a fighter in the first installment in 1999.[96] Ness's inclusion in the original release was among its biggest surprises,[97][nb 17] and renewed Mother series fans' faith in new content from Nintendo.[66] Ness was one of the game's most powerful characters, according to IGN, if players could perfect his odd controls and psychic powers.[97] In Europe, which did not see an EarthBound release, Ness was better known for his role in the fighting game than for his original role in the role-playing game.[100]

Ness returned in the first sequel, Melee, alongside an EarthBound-themed item and battle arena.[97][nb 18] Lucas, the protagonist of Mother 3, joined Ness in Brawl.[102][103][nb 19] Several years after Brawl's release, Official Nintendo Magazine wrote that Ness was an unpopular Smash character who should be removed from future installments.[100] However, Ness returned in Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U and Ultimate,[106] and Lucas was later added to the former as downloadable content.[107]

Sequels and rereleases

[edit]In 1996, Nintendo announced a sequel to EarthBound for the Nintendo 64: Mother 3[26] (EarthBound 64 in North America).[108] It was scheduled for release on the 64DD, a Nintendo 64 expansion peripheral that used a magneto-optical drive,[44] but struggled to find a firm release date[109] as its protracted development entered development hell. It was later canceled altogether in 2000[26] when the 64DD flopped.[44] In April 2003, a Japanese television advertisement revealed that both Mother 3 and a combined Mother 1+2 cartridge were in development for the handheld Game Boy Advance.[110] Mother 3 abandoned the Nintendo 64 version's 3D, but kept its plot.[26] It became a bestseller upon its Japanese release in 2006, yet did not receive a North American release[44] on the basis that it would not sell.[41] IGN described the series as neglected by Nintendo in North America, as Mother 1, Mother 1+2 and Mother 3 were not released outside Japan.[66]

When Nintendo launched its digital distribution platform, Virtual Console, for the Wii in 2006, IGN expected EarthBound to be among Nintendo's highest priorities for rerelease, given the "religious" dedication of its fanbase.[66] Though the game was ranked the most desired Virtual Console release by Nintendo Power readers, rated for release by the ESRB,[112] and able to be published with little effort,[26] the Wii version did not materialize.[18] Many fans believed that music licensing or legal concerns impeded the rerelease.[15][26][111] English localizer Marcus Lindblom doubted that the game's music samples were an issue, since they were not a concern during development, and instead hypothesized that Nintendo did not realize the magnitude of the game's popular support and did not consider it a priority project.[15] By 2008, it was not apparent that Nintendo of America was considering a rerelease.[26] At the end of 2012, Itoi revealed that the re-release was moving forward,[41] which was confirmed in a January 2013 Nintendo Direct presentation.[113]

As part of the anniversary celebrations for the Nintendo Entertainment System and Mother 2 in March 2013, Nintendo rereleased EarthBound for Japan on the Wii's successor, the Wii U Virtual Console.[113] EarthBound producer Satoru Iwata soon announced a wider rerelease, citing fan interest on Nintendo's Miiverse social platform.[83] The July American and European launch included a free, online recreation of the game's original Player's Guide, optimized for viewing on the Wii U GamePad.[114] The game was a top-seller on the Wii U Virtual Console, and both Kotaku users and first-time EarthBound players had an "overwhelmingly positive" response to the game.[15] Simon Parkin wrote that its re-release was a "momentous occasion" as the return of "one of Nintendo's few remaining lost classics" after 20 years.[17] The re-release was one GameSpot editor's game of the year,[115] and Nintendo Life's Virtual Console game of the year.[116] The New Nintendo 3DS-specific Virtual Console received the re-release the next year, in March 2016.[117] In September 2017, Nintendo released the Super NES Classic Edition, which included EarthBound among its games.[118] Japan's version of the console however, did not include the game.[119]

In February 2022, Nintendo rereleased EarthBound worldwide on its Nintendo Switch Online service along with its predecessor EarthBound Beginnings.[120]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pax Softnica developed the Game Boy Advance port.

- ^ Japanese: MOTHER2ギーグの逆襲, Hepburn: Mazā Tsū: Gīgu no Gyakushū, lit. Mother 2: Giygas' Counterattack

- ^ If the counter reaches zero as the battle is won, it will be set to 1 HP instead and the character will survive.

- ^ The only reference to the year in the game is represented with "199X".

- ^ Players are asked to name their characters at the beginning of the game. "Ness", along with all the other names for the playable characters in this article, are the default names.[9]

- ^ While named Pokey in EarthBound, he is named Porky in the Japanese version. This also applies in Mother 3. In Japanese versions of both his name is ポーキー Pōkī.[11]

- ^ It was later reprinted by Sony Music Direct on February 18, 2004.[29]

- ^ Within a year following the game's release, Keiichi Suzuki recorded a cover version of the Beach Boys' "Good Vibrations" (1966), a product of the band's Smile album where Parks served as a primary lyricist.[32]

- ^ These quotations and samples are believed to include the Beach Boys ("Deirdre"),[33] the Beatles ("Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band"), the Who ("Won't Get Fooled Again"), Antonín Dvořák (Symphony No. 9), Ric Ocasek ("This Side of Paradise"), the Doors ("The Changeling"), Bimbo Jet ("El Bimbo"), The Dallas String Band ("Dallas Rag"), "The Liberty Bell", "The Star-Spangled Banner", the Our Gang theme, "Tequila", and Chuck Berry ("Johnny B. Goode").[15]

- ^ In these sectors, Tanaka cited influence from Andy Partridge of XTC's Take Away / The Lure of Salvage (1980), Lalo Rodríguez's Un Nuevo Despertar (1988) and Fireworks (1976), King Tubby/Yabby You's King Tubby's Prophesy of Dub (1976), and the Flying Lizards' The Secret Dub Life of the Flying Lizards (1995).[31]

- ^ The compilation operates under the premise of pop artists "on the cutting edge of technology in music".[34]

- ^ They include Prince's Around the World in a Day (1985) and Sign o' the Times (1987), Godley & Creme's Consequences (1977), A Tribe Called Quest's People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm (1990) and My Bloody Valentine's Loveless (1991).[31]

- ^ While working alone was standard for localizers of the era, later localization efforts had full departments.[18]

- ^ Lindblom thought reviewers viewed the game's visuals as "enhanced 8-bit graphics", which, he added, would "ironically" fit 2013's retrogaming aesthetic.[35]

- ^ He thought the final scene was "perhaps the most clever and powerful moment in a clever and powerful game".[68]

- ^ For instance, Lindblom rejected a popular, or infamous, "abortion theory": that the game's final sequence is a metaphor for an abortion,[15] with Giygas as the fetus.[12] He also provided a floppy disk whose recovered data provided extra context into the game's development errata.[91]

- ^ Ness's original Super Smash Bros. spot was actually intended for Mother 3 protagonist Lucas, but the developers later fit Ness into the character design[98] when Mother 3 was delayed.[99]

- ^ Melee players toss Mr. Saturn items at enemies,[97] and fight in an arena based on the EarthBound city of Fourside.[101]

- ^ Brawl also contains the final area from Mother 3 along with items and characters from the game,[104] and a boss fight against Mother 3's antagonist, Porky.[105]

References

[edit]- ^ "MOTHER2 ギーグの逆襲/EarthBound / ハル研究所". HAL Laboratory. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ "MOTHER2 ギーグの逆襲". Nintendo (in Japanese). Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ ""Game Boy Advance March 2001 - January 2005 Releases Section"". www.nintendo.co.jp. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Parkin, Simon (October 29, 2008). "Mother 3 Review". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Nintendo of America, ed. (1995). EarthBound Player's Guide (PDF). Nintendo of America, Inc. pp. 10, 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2024. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Interview with Shigesato Itoi". Weekly Famitsu (in Japanese): 21–23. September 2, 1994.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy (April 13, 2006). "Retronauts 5: Earthbound". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Nintendo of America, ed. (1995). EarthBound Player's Guide. Nintendo of America, Inc. p. 12.

- ^ a b Sinclair, Brendan (July 19, 2013). "What's the Deal With Earthbound?". USgamer. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sanchez, David (September 8, 2013). "Review: EarthBound returns to prove why it's one of the greatest RPGs of all time". GameZone. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Oxford, Nadia (July 23, 2013). "EarthBound's Ten Most Memorable Moments". IGN. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Schreier, Jason (April 20, 2012). "Earthbound, The Trippiest Game In RPG History". Kotaku. Archived from the original on June 8, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Tilden, Gail, ed. (1995). EarthBound Player's Guide. Nintendo of America. p. 109. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021.

- ^ Tilden 1995, pp. 116–119.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Schreier, Jason (August 23, 2013). "The Man Who Wrote Earthbound". Kotaku. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e George, Richard. "EarthBound - #13 Top 100 SNES Games". IGN. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Parkin, Simon (September 21, 2013). "Earthbound review". Official Nintendo Magazine. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Campbell, Colin (January 18, 2014). "Why did Nintendo quash a book about EarthBound's development?". Polygon. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ a b c Itoi, Shigesato (August 22, 2000). "『MOTHER 3』の開発が中止になったことについての" [About the development of "MOTHER 3" has been canceled]. 1101.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved August 30, 2014. Translation Archived November 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Translated introduction Archived November 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Shigesato Itoi Tells All about Mother 3 (Part Two)". Nintendo Dream. August 2006. p. 7. Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2014. Translation Archived December 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e "Interview with Kouji Malta and Satoru Iwata". Weekly Famitsu (in Japanese): 72–73. September 9, 1994.

- ^ "Mother 2". Weekly Famitsu (in Japanese): 149–153. June 19, 1994.

- ^ Itoi, Shigesato (April 24, 2003). "『MOTHER』の気持ち。" [Feeling of "MOTHER"]. 1101.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ "Mother 2". Super Famicom Magazine (in Japanese). 5: 70–71. November 10, 1992.

- ^ "Mother 2". Weekly Famitsu (in Japanese): 170. July 15, 1994.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Linde, Aaron (May 6, 2008). "EarthBotched: A History of Nintendo vs. Starmen". Shacknews. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Davis, Justin (April 29, 2013). "Eight of the most hilarious anti-piracy measures in video games". IGN. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ "EarthBound Credits". Mobygames.com. Mobygames. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c Chorley, Vincent. "Mother 2: Gigya's Counterattack". RPGFan. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Interview with Keiichi Suzuki". Weekly Famitsu (in Japanese): 12. October 28, 1994.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Itoi, Shigesato (June 16, 2003). "『MOTHER』の音楽は鬼だった。" [Music of "MOTHER" was a demon]. 1101.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2014. Translated into English by a fan.

- ^ "Discography / Others". keiichisuzuki.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "The Beatles, Beach Boys and Monty Python really were in Earthbound". Destructoid. June 28, 2014. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ Pearson, Paul. "Wired Magazine Presents: Music Futurists". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Meyer, John Mix (July 23, 2013). "Octopi! Spinal Tap! How Cult RPG EarthBound Came to America". Wired. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ "1994年のコンシューマーゲームソフトの売上" [1994 Consumer Game Software Sales]. Dengeki Oh (in Japanese). MediaWorks. Archived from the original on September 20, 2001. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ Consalvo, Mia (April 8, 2016). Atari to Zelda: Japan's Videogames in Global Contexts. MIT Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-262-03439-5. Archived from the original on February 25, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Roberts, David (April 15, 2015). "The totally radical history of game marketing in the '90s". GamesRadar+. p. 7. Archived from the original on July 6, 2024. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

But some ad exec must have seen a single picture of Master Belch and decided that EarthBound was nothing but gross-out humor, and decided to revolve the entire ad campaign around it. [...] There are a lot of reasons EarthBound tanked in the West, but a large part of it was due to this ad (and its accompanying Scratch-n-sniff cards).

- ^ Oxford, Nadia (August 31, 2017). "Super NES Retro Review: EarthBound". VG247. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

Though Nintendo spent a lot of money on a great localization for EarthBound, it literally blew the game's advertising campaign with ads about farts and poops. That was an immediate turn-off for newly-minted RPG enthusiasts (myself included) [...]

- ^ Chan, Khee Hoon (February 1, 2019). "Piracy helped Earthbound become a cult classic". Polygon. Archived from the original on December 27, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

The game's marketing campaign compounded the issue. It was unabashedly juvenile, filled with gross-out humor and self-deprecating proclamations about how "this game stinks," which were accompanied by scratch-and-sniff ads. These pages left a literal stench in gaming magazines. [...] Nonetheless, EarthBound still managed to inch its way toward cult status as the years went on and the ROM was traded among fans and shared online.

- ^ a b c d Agnello, Anthony John (December 21, 2012). "EarthBound Creator Shigesato Itoi Teases a Rerelease for His Cult RPG". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (June 26, 2013). ""What The F**k Kind Of Game Is Earthbound?"". Kotaku. Archived from the original on July 6, 2024. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

- ^ "When Ads Go Bad, Readers Get Mad". GamePro. No. 91. IDG. April 1996. p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f Cowan, Danny (February 7, 2007). "Vapor Trails: The Games that Never Were". 1UP.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ "New Games Cross Review". Weekly Famitsu. Enterbrain. September 23, 1994.

- ^ a b Halverson, Dave, ed. (August 1995). "Viewpoint: EarthBound". DieHard GameFan (32): 15.

- ^ "EarthBound- Super NES". Game Informer. Archived from the original on November 20, 1997. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Kamikaze, Marcelo (July 16, 1995). Barros, Rubem (ed.). "SNES: EarthBound". Super GamePower (in Portuguese) (16): 26–27. ISSN 0104-611X.

- ^ GameFan, volume 4, issue 1, pages 104-106

- ^ a b c d e f Mackey, Bob (March 2010). "Posthumous Cult Gaming". 1UP.com. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 13, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ^ a b Des Barres, Nicholas Dean (August 1995). "GameFan 16: EarthBound". DieHard GameFan (32): 70–71.

- ^ Sir Scary Larry (July 1995). "EarthBound". GamePro. No. 82. IDG. pp. 74–75.

- ^ "EarthBound". GameRankings. Archived from the original on January 9, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- ^ House, Michael L. "EarthBound Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Thompson, Scott (July 24, 2013). "EarthBound Review". IGN. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c Baker, Justin (July 27, 2013). "EarthBound Review Mini". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Frear, Dave (February 11, 2022). "EarthBound Review (SNES)". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Earthbound review". GamesTM. October 7, 2013. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Donlan, Christian (2010). "EarthBound". In Mott, Tony (ed.). 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die. New York: Universe. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-7893-2090-2. OCLC 754142901.

- ^ Kalata, Kurt (March 19, 2008). "A Japanese RPG Primer: The Essential 20". Gamasutra. UBM Tech. p. 10. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Bell, Lowell (February 25, 2023). "Best JRPGs Of All Time". Time Extension. Hookshot Media. Archived from the original on September 21, 2023. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ Edge Staff (March 3, 2006). "Japan Votes on All Time Top 100". Edge. Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ "IGN and KFC Snacker Present Readers' Top 99 Games". IGN. April 11, 2005. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ "IGN Readers' Choice 2006 – The Top 100 Games Ever". IGN. 2006. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ a b "EarthBound - #26 Top Video Game Worlds". IGN. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Thomas, Lucas M. (August 17, 2006). "Retro Remix: Round 25". IGN. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Knight, Rich (April 30, 2018). "The Best Super Nintendo Games of All Time". Complex. Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c Parish, Jeremy (June 5, 2013). "Metatext: Separating the Player from the Character". USgamer. Archived from the original on July 6, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Sykes, Tom (February 22, 2015). "YIIK: A Postmodern RPG is a psychedelic indie Earthbound". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on February 24, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- ^ Nutt, Christian (October 20, 2010). "Interview: Double Fine's Harris - From Pixar To Costume Quest". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Harris, Tasha (October 6, 2010). "5 Inspirations Behind Costume Quest, Coming to PS3 October 19th". PlayStation Blog. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (July 18, 2013). "'South Park' creators explain how The Stick of Truth got too big for its own good". Polygon. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Gilbert, Henry (July 22, 2013). "South Park: The Stick of Truth is inspired by Earthbound, sounds really tough to make". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Schilling, Chris (May 5, 2018). "The making of Undertale". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ a b LaBella, Anthony (September 24, 2015). "You Should Play Undertale". Game Revolution. CraveOnline. Archived from the original on December 13, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy (April 13, 2006). "Contact". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ McFerran, Damien (December 15, 2021). "EarthBound-Style Horror RPG OMORI Is Finally Coming To Switch After Skipping The 3DS". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on May 1, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Adam (November 26, 2013). "The Sacrificial Limb: LISA – The Painful RPG". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Malina, Tom (March 27, 2013). "Earthbound-Inspired RPG Citizens of Earth Targets Wii U eShop Next Year". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Frank, Allegra (August 29, 2016). "Try Y2K: A Postmodern RPG for free next week". Polygon. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- ^ "What exactly is Homestuck?". ResetEra. September 17, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ Wawro, Alex (May 22, 2014). "Finding comfort in a pet project: The Bushido Blade-inspired Kyoto Wild". Gamasutra. UBM Tech. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ a b McElroy, Griffin (April 17, 2013). "EarthBound coming to Wii U Virtual Console in North America and Europe this year". Polygon. Archived from the original on February 14, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Caron, Frank (October 28, 2008). "Mama's boys: the epic story of the Mother 3 fan translation". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c Mackey, Bob (March 2010). "Posthumous Cult Gaming". 1UP.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ^ Fahey, Mike (October 17, 2008). "Mother 3 Fan Translation Completed". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ^ Lopez, Alan (October 26, 2019). "Feature: How Fangamer Changed The World Of Video Game Merchandise Forever". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (July 18, 2013). "Cult classic 'Earthbound' launches today on Wii U". The Verge. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Macy, Seth G. (April 25, 2014). "EarthBound Documentary Announced". IGN. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ^ Schreier, Jason (August 19, 2013). "Oh Jeez, The Fan-Made Mother 4 Looks Amazing, And It's Out Next Year". Kotaku. Archived from the original on August 22, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ^ Machkovech, Sam (June 4, 2021). "'Deleted' Nintendo floppy recovered 26 years later, full of Earthbound secrets". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- ^ "Earthbound by Ken Baumann: New Boss Fight Book on the SNES RPG Classic - Boss Fight Books". Archived from the original on December 27, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ "Legends of Localization Book 2: Earthbound - Fangamer". Archived from the original on December 27, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ "Earthbound Figures Of Ness, Paula, And Mr. Saturn Coming Out In Japan". Siliconera. July 8, 2014. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ "Guide: Best amiibo For Nintendo Switch". Nintendo Life. November 24, 2019. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ Macy, Seth G. (October 3, 2014). "NINTENDO REVEALS SECRET SMASH BROS. FIGHTERS COMING TO WII U". IGN. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c d IGN Staff (June 27, 2001). "Smash Profile: Ness". IGN. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ 速報スマブラ拳!! : ネス [Breaking Fist Smash Bros.:! Ness]. Nintendo (in Japanese). July 17, 2001. Archived from the original on August 18, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

実は当初、MOTHER3の主人公に変更する予定でしたが、いろいろあって遠回りしながら、元のさやに収まりました。

- ^ Kolan, Patrick (May 31, 2007). "SUPER SMASH BROS: EVOLUTION". IGN. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ^ a b East, Thomas (September 11, 2012). "Smash Bros characters who need to be dropped for Wii U and 3DS". Official Nintendo Magazine. Archived from the original on October 8, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ IGN Staff (December 3, 2001). "Unlock SSB Melee Secrets!". IGN. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Thomas, Lucas M. (February 1, 2006). "Smash It Up! – The Final Roster". IGN. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Thomas, Lucas M. (November 16, 2007). "Smash It Up! – Veterans Day". IGN. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Gamin, Mike (February 12, 2008). "Super Smash Bros. Brawl". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ East, Tom (March 17, 2008). "Smash Bros. Boss Screens". Official Nintendo Magazine. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Bailey, Kat (September 20, 2014). "Time to Bid Farewell to these Smash Bros. Characters". USgamer. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

- ^ Tach, Dave (June 5, 2015). "Lucas joins Super Smash Bros. June 14 alongside Splatoon outfits". Polygon. Archived from the original on June 8, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ Haywald, Justin (October 30, 2016). "6 Games That Came Back From the Dead". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ IGN Staff (March 22, 2000). "MOTHER 3 PUSHED BACK". IGN. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ GameSpot Staff (April 14, 2003). "Original Earthbound and sequels in development for the GBA". GameSpot. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- ^ a b Schreier, Jason (April 19, 2013). "Maybe The Earthbound Delay Wasn't Really For Music Licensing Issues". Kotaku. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ van Duyn, Marcel (May 2, 2008). "ESRB Update: EarthBound Finally Coming To Virtual Console!". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Sarkar, Samit (January 23, 2013). "EarthBound launching on Japanese Wii U Virtual Console in March". Polygon. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Sarkar, Samit (July 18, 2013). "EarthBound now available on Wii U Virtual Console for $9.99". Polygon. Archived from the original on November 29, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Haywald, Justin (December 18, 2013). "Can I make this a 'top 30'?". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 16, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Whitehead, Thomas (December 30, 2013). "Game of the Year: Nintendo Life's Staff Awards 2013". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Karklins, Andrew (March 3, 2016). "SNES Games Finally Arriving on the New Nintendo 3DS Virtual Console". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2017. For information on its exclusivity, see Buckley, Sean (March 3, 2016). "Nintendo makes SNES games exclusive to 'New' Nintendo 3DS". Engadget. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 26, 2017. and Miller, Matt (March 9, 2016). "Nintendo Explains Why SNES Games Will Only Run On New 3DS". Game Informer. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ "Super NES Classic Edition". Nintendo of America, Inc. September 29, 2017. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021.

- ^ Ashcraft, Brian (June 28, 2017). "It's Strange That Mother 2 Isn't On The Super Famicom Classic". Kotaku. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ Diaz, Ana (February 9, 2022). "EarthBound will hit the Nintendo Switch on Feb. 9". Polygon. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to EarthBound at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to EarthBound at Wikimedia Commons

- 1994 video games

- Video games about alien invasions

- Censored video games

- Video games about dinosaurs

- Game Boy Advance games

- HAL Laboratory games

- Fiction about the Hollow Earth

- Japanese role-playing video games

- Mother (video game series)

- Nintendo Switch Online games

- Parody video games

- Satirical video games

- Science fantasy role-playing video games

- Science fiction comedy

- Single-player video games

- Super Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Video game sequels

- Video games about psychic powers

- Video games about time travel

- Video games scored by Hirokazu Tanaka

- Video games scored by Keiichi Suzuki

- Video games set in the 1990s

- Video games set in North America

- Video games with oblique graphics

- Virtual Console games for Nintendo 3DS

- Virtual Console games for Wii U

- Ape Inc. games