Blueshirts

| Army Comrades Association | |

|---|---|

| |

| Also known as | Blueshirts |

| Leader | Ned Cronin[1] Eoin O'Duffy[2] Thomas F. O'Higgins Ernest Blythe |

| Foundation | 9 February 1932 |

| Dissolved | 1935 |

| Merged into | Fine Gael (pro-Cronin faction) |

| Country | |

| Newspaper | The Nation |

| Ideology | Anti-communism Irish nationalism Integral nationalism Corporate statism[3] National Catholicism[4] |

| Political position | Far-right[5] |

| Size | 8,337 (October 1932) 38,000 (March 1934) 48,000 (peak; August 1934) 4,000 (September 1935)[6] |

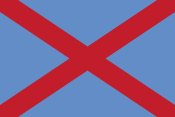

| Flag |  |

The Army Comrades Association (ACA), later the National Guard, then Young Ireland[a] and finally League of Youth, but best known by the nickname the Blueshirts (Irish: Na Léinte Gorma), was a paramilitary organisation in the Irish Free State, founded as the Army Comrades Association in Dublin on 9 February 1932.[7] The group provided physical protection for political groups such as Cumann na nGaedheal from intimidation and attacks by the IRA.[8] Some former members went on to fight for the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War after the group had been dissolved.

Most of the political parties whose meetings the Blueshirts protected would merge to become Fine Gael, and members of that party are still sometimes nicknamed "Blueshirts".[9] There has been considerable debate in Irish historiography over whether or not it is accurate to describe the Blueshirts as fascists.[9]

History

[edit]Origins and early history

[edit]In February 1932, the Fianna Fáil party was elected to lead the Irish Free State government. On 18 March 1932, the new government suspended the Public Safety Act, lifting the ban on a number of organisations including the Irish Republican Army. Some IRA political prisoners were also released around the same time. The IRA and many released prisoners began a "campaign of unrelenting hostility" against those associated with the former Cumann na nGaedheal government. Frank Ryan, one of the most prominent socialists in 1930s Ireland, active in both the Republican Congress and the IRA, declared "as long as we have fists and boots, there will be no free speech for traitors".[10] There were many cases of intimidation, attacks on persons, and the breaking-up of Cumann na nGaedheal political meetings in the coming months. In view of the increased activities of the IRA, National Army Commandant Ned Cronin founded the Army Comrades Association in Dublin on 11 August 1932.[7] As its name suggested, it was designed for Irish Army veterans, a society for former members of the Free State army. The ACA felt that freedom of speech was being repressed, and began to provide security at Cumann na nGaedheal events. This led to several serious clashes between the IRA and the ACA. In August 1932, Thomas F. O'Higgins became the leader of the ACA. O'Higgins was joined in the organisation by fellow Cumann na nGaedhael TDs Ernest Blythe, Patrick McGilligan and Desmond Fitzgerald.[9] O'Higgins had been chosen as leader partially because his brother Kevin O'Higgins, who had been Cumann na nGaedheal Minister for Justice, had been assassinated by the IRA in 1927.[11][12] [7] By September 1932 the organisation claimed it had over 30,000 members.[13] The historian Mike Cronin believes the Blueshirts regularly embellished their numbers and the actual amount was closer to 8,000 at that point.[6] Women members were termed "Blue Blouses".[14]

Eoin O'Duffy becomes leader

[edit]

In January 1933, the Fianna Fáil government called a surprise election, which the government won comfortably. The election campaign saw a serious escalation of rioting between IRA and ACA supporters. In April 1933, the ACA began wearing the distinctive blueshirt uniform. Eoin O'Duffy was a guerrilla leader in the IRA in the Irish War of Independence, a National Army general in the Irish Civil War, and the Garda Síochána police commissioner in the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1933. After Fianna Fáil's re-election in February 1933, President of the Executive Council Éamon de Valera dismissed O'Duffy as commissioner after learning O'Duffy had considered staging a coup d'état to remove him from power.[15] That July, O'Duffy was offered and accepted leadership of the ACA and renamed it the National Guard. He re-modelled the organisation, adopting elements of European fascism, such as the straight-arm Roman salute, the wearing of uniforms and huge rallies. Membership of the new organisation became limited to people who were Irish or whose parents "profess the Christian faith". O'Duffy was an admirer of Benito Mussolini, and the Blueshirts adopted corporatism as a chief political aim. According to the constitution he adopted, the organisation was to have the following objectives:[16]

- To promote the re-union of Ireland.

- To oppose Communism and alien control and influence in national affairs and to uphold Christian principles in every sphere of public activity.

- To promote and maintain social order.

- To make organised and disciplined voluntary public service a permanent and accepted feature of our political life and to lead the youth of Ireland in a movement of constructive national action.

- To promote the formation of co-ordinated national organisations of employers and employed, which, with the aid of judicial tribunals, will effectively prevent strikes and lock-outs and harmoniously compose industrial influences.

- To co-operate with the official agencies of the state for the solution of such pressing social problems as the provision of useful and economic public employment for those whom private enterprise cannot absorb.

- To secure the creation of a representative national statutory organisation of farmers, with rights and status sufficient to secure the safeguarding of agricultural interests, in all revisions of agricultural and political policy.

- To expose and prevent corruption and victimisation in national and local administration.

- To awaken throughout the country a spirit of combination, discipline, zeal and patriotic realism which will put the state in a position to serve the people efficiently in the economic and social spheres.

March on Dublin

[edit]The National Guard planned to hold a parade in Dublin in August 1933. It was to proceed to Glasnevin Cemetery, stopping briefly on Leinster lawn in front of the Irish parliament, where speeches were to be held. The goal of the parade was to commemorate Irish leaders Arthur Griffith, Michael Collins and Kevin O'Higgins. It is clear that the IRA and other fringe groups representing various socialists intended to confront the Blueshirts if they marched in Dublin.

On 22 August 1933 the Fianna Fáil government, remembering Mussolini's March on Rome, and fearing a coup d'état, invoked article 2A of the constitution and banned the parade.[9] Decades later, de Valera told Fianna Fáil politicians that in late summer 1933 he was unsure whether the Irish Army would obey his orders to suppress the perceived threat, or whether the soldiers would support the Blueshirts (who included many ex-soldiers). O'Duffy accepted the ban and insisted that he was committed to upholding the law. Instead, several provincial parades took place to commemorate the deaths of Griffith, O'Higgins and Collins. De Valera saw this move as defying his ban, and the Blueshirts were declared an illegal organisation.[9]

Merging with Cumann na nGaedhael and the National Centre Party to form Fine Gael

[edit]

In response to the banning of the National Guard, Cumann na nGaedheal and the National Centre Party merged to form a new party, Fine Gael, on 3 September 1933. O'Duffy became its first president, with W. T. Cosgrave and James Dillon acting as vice-presidents. O'Duffy was chosen as leader instead of Cosgrave and MacDermot in order to avoid the idea that Fine Gael would simply be a continuation of Cumann na nGaedhael.[9] The National Guard changed its name to the Young Ireland Association, and became part of a youth wing of the party. The new party's stated aim was to create a united Ireland within the British Commonwealth, although its programme made no mention of a corporatist state.[17] In fact, the original name considered for the party was "The United Ireland Party" until Fine Gael was settled on.[9] Labour Party leader William Norton was unimpressed; he surmised the new entity as "an attempt to put old wine in new bottles”.[9] Seán Lemass dismissed this triple alliance as "the cripple alliance".[18]

In March 1934 the Minister for Justice P. J. Ruttledge of Fianna Fáil brought forward a Wearing of Uniforms (Restriction) Bill which specifically sought to ban political uniforms in Irish public life. Badges, banners and military titles that were considered at odds with public peace were also to be prohibited. Ruttledge outright said as much that part of the aim was to end the Blueshirts, although said that in practice it would apply to every part of the political spectrum. However, following bitter debates in the Dáil, the bill was voted down in the Seanad 30 to 18.[9]

The 1934 local elections, in June 1934, were a trial of strength for the new Fine Gael and the Fianna Fáil government. When Fine Gael won only six out of 23 local elections, O'Duffy lost much of his authority and prestige.[9] The Blueshirts had peaked by mid-1934 and rapidly began to disintegrate.[13] A number of anti-establishment incidents were attributed to the Blueshirts during 1934, including their campaign against the payment of land annuities.[19] The Blueshirts began to flounder on the plight of farmers in the Economic War, as the Blueshirts failed to provide a solution.[9] In response to this, O'Duffy began to ramp up his extremist rhetoric. However, this prompted elements of Fine Gael such as Ernest Blythe, Michael Tierney and Desmond FitzGerald to begin working to remove O'Duffy from power.

Following disagreements with his Fine Gael colleagues, O'Duffy left the party in September 1934, although most of the Blueshirts stayed in Fine Gael. Following O'Duffy's ascent to leadership of Fine Gael, control of the Blueshirts had been left to original Blueshirt founder Ned Cronin. When O'Duffy left Fine Gael, he attempted to resume this position, however, Cronin resisted, resulting in the Blueshirts splitting into pro-O'Duffy and pro-Cronin factions. Cronin and his faction wished to remain within Fine Gael while O'Duffy's faction left entirely. Cronin's faction seemed to have been the majority of the membership.[20]

In December 1934, O'Duffy attended the Montreux Fascist conference in Switzerland. He then founded the National Corporate Party, and later raised an Irish Brigade that took General Francisco Franco's side in the Spanish Civil War, with disastrous results.[21] Meanwhile, Fine Gael was brought back under the leadership of WT Cosgrove who had previously led Cumann na nGaedhael. Now acting as Deputy Leader was James Dillon, formerly of the National Centre Party, who helped reinforce pro-democratic views into the party. Dillon was a staunch defender of liberal democracy[22] who in later years denounced Nazism as "the devil himself with twentieth-century efficiency".[23] He resigned from Fine Gael in 1942 due to his belief that Ireland should break neutrality and join the Allies to fight against Hitler.[24] He later rejoined the party and became its leader after Richard Mulcahy.

Legacy

[edit]As a rule, the modern Fine Gael party strenuously avoids referring to the Blueshirts as having been a part of the founding of the party, although it is happy to acknowledge the lineage of Cumann na nGaedhael and the National Centre Party, as well as to draw a lineage back to Michael Collins.[9] Above all, Eoin O'Duffy is never acknowledged as its first leader, instead W. T. Cosgrave is given the mantle. Nonetheless, "Blueshirt" continues to be used as a pejorative for members of Fine Gael to this day.[25][26][9]

Fascism debate

[edit]

Considerable debate has been held in Irish society across many decades over whether or not it is accurate to describe the Blueshirts as fascists.[9][27]

Stanley G. Payne has argued that the Blueshirts "really was never a fascist organization at all".[28] Maurice Manning also did not consider them fascists, with their mixture of patriotic conservatism, militia activities and corporatism amounting "to no more than a kind of Celtic Croix-de-Feu",[29] and that ultimately the Blueshirts "had much of the appearance but little enough of the substance of Fascism".[30] Historians are divided on the extent to which the Blueshirts took a lead from Mussolini and his many imitators at that time.[31][32] Some of the Blueshirts later went to fight for Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War because of his anti-communism. They imitated some aspects of the Mussolini movement, such as the coloured-shirt uniform, Roman salute and the March on Rome; however, Historian R. M. Douglas has opined that it is incorrect to portray them as an "Irish manifestation of fascism".[33]

Mike Cronin, an academic specialising in Irish political and cultural history, also concludes that the Blueshirts "undoubtedly possessed certain fascist traits, but they were not fascists in the German or Italian sense". Instead, Cronin suggests the term "Para-fascists" is more appropriate, indicating that while they took on the outward trapping of fascism, they did not commit to the more radical elements. Cronin contends that while certain members of the Blueshirts did hold fascist views, they were effectively "drowned out" by the number of traditionally conservative members, particularly after the merger into Fine Gael. Nonetheless, Cronin also notes that the Blueshirts' potential for outright fascism should not be dismissed either.[34]

Fearghal McGarry of Queen's University Belfast, has suggested that while O'Duffy can be thought of as a genuine fascist, despite his role as the leader he was not representative of the bulk of the blueshirt membership, and that the degree to which the Blueshirts should be thought of as fascists has been overemphasised by Irish Republicans in order to reinforce their anti-fascist credentials during the interwar period. McGarry has said the danger from the Blueshirts was not that they would turn Ireland into Fascist Italy, but into the Portuguese dictatorship that existed under Salazar at the time.[35]

Paul Bew has also argued against the term fascist being applied to the Blueshirts, instead labelling them as "angry rural conservatives" engaged in populism, with the views of the average member being closer to that of the Irish Parliamentary Party or the Irish Land League than Italian Fascism.[36][10] On the same line, Alvin Jackson has stated that while some of the Cumann na nGaedheal leadership "flirted with paramilitarism and the trappings of fascism", in his view "O’Duffy’s fondness for outrageous rhetoric and elaborate uniforms was more O'Connellite than Hitlerian".[37][38] Historian J. J. Lee has remarked that "Fascism was far too intellectually demanding for the bulk of the Blueshirts"[39] Marxist historian John Newsinger disputes this line of thinking somewhat by agreeing that the rank and file of the Blueshirts were not ideologically fascists, but so long as the leadership was, the consequences of the Blueshirts coming to power would have been one-party state dictatorship.[38]

Michael O'Riordan, an Irish anti-fascist who fought in the Spanish Civil War and led the Communist Party of Ireland for many decades, said of the ex-Blueshirts who later volunteered to fight in Spain: "I never regarded them as fascists. They saw themselves as involved in a Christian crusade against 'godless communism' in Spain; at worst, then, they were dupes."[10]

In the aftermath of O'Duffy's departure from Fine Gael, most of the party settled back into "traditional" conservatism under the leadership of WT Cosgrove and James Dillon. However, this was not true of all of the membership. Ernest Blythe, the Cumann na nGaedhael minister who had been an enthusiastic member of the Blueshirts and heavily supported its gravitation towards corporatism, continued to support fascist causes in Ireland many years after the Blueshirts' demise. Blythe retired from public life in 1936 after the abolishment of the Senate but he continued to engage in politics. During the 1940s he supported and aided the openly fascist Ailtirí na hAiséirghe.[40] Blythe advised Ailtirí na hAiséirghe's leader Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin on the drafting of the party's constitution, gave it backing in its journal The Leader, as well as making financial contributions towards the party.[41] During the 1940s Blythe's activities alarmed Ireland's secret intelligence agency G2, whose intelligence files referred to him as a potential "Irish Quisling" and “100 per cent Nazi”.[42]

Some commentators have suggested that rather than view the conflict between the Blueshirts and the IRA through the prism of fascism vs anti-fascism, in reality, the conflict should be seen as more akin to a political rehashing of the Irish Civil War that began against the backdrop of Fianna Fáil entering into government for the first time.[43]

See also

[edit]- Category:Members of the Blueshirts - A list of notable members of the Blueshirts

- Ailtirí na hAiséirghe - A 1940s Irish political party whose Fascism is not disputed

- Irish Christian Front - A mid-1930s pro-Franco group in Ireland

- Greenshirts - O'Duffy's successor party to the Blueshirts

Notes

[edit]- ^ Young Ireland was historically the name of a 19th Century Irish revolutionary movement. There is, however, no organizational continuity - and little ideological similarity - between it and the 20th century movement.

References

[edit]- ^ Cronin, M.; Regan, J. (2000). Ireland: The Politics of Independence, 1922-49. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 65. ISBN 9780230535695.

- ^ McGarry, Fearghal (2005). Eoin O'Duffy: A Self-Made Hero. OUP Oxford. p. 209. ISBN 0199276552.

- ^

Badie, Bertrand; Berg-Schlosser, Dirk; Morlino, Leonardo, eds. (7 September 2011). International Encyclopedia of Political Science. SAGE Publications (published 2011). ISBN 9781483305394. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

[...] fascist Italy [...] developed a state structure known as the corporate state with the ruling party acting as a mediator between 'corporations' making up the body of the nation. Similar designs were quite popular elsewhere in the 1930s. The most prominent examples were Estado Novo in Portugal (1932-1968) and Brazil (1937-1945), the Austrian Standestaat (1933-1938), and authoritarian experiments in Estonia, Romania, and some other countries of East and East-Central Europe,

- ^ Stanley G. Payne (1984). Spanish Catholicism: An Historical Overview. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-299-09804-9.

- ^ O'Connor, Eimear (2009). Sean Keating in Context: Responses to Culture and Politics in Post-civil War Ireland. Carysfort Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1904505419.

- ^ a b Cronin, Mike (1994). "The Socio-Economic Background and Membership of the Blueshirt Movement, 1932-5". Irish Historical Studies. 29 (114): 234–249. doi:10.1017/S0021121400011597. JSTOR 30006744. S2CID 163560931. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ a b c New Irish Army Arises, New York Times, August 12, 1932

- ^ R. M. Douglas, "Architects of the Resurrection: Ailtirí na hAiséirghe and the Fascist 'New Order' in Ireland, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-7998-5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Collins, Stephen (7 November 2020). "Without the Blueshirts, there would have been no Fine Gael". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Garvin, Tom (12 January 2001). "Showing Blueshirts in their true colours". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ White, Lawrence William. "O'Higgins, Thomas Francis ('T. F.')". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ McCarthy, John P. "O'Higgins, Kevin Christopher". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ a b Mark Tierney, OSB, MA "Modern Ireland", Gill & Macmillan, 1972 p 175-182

- ^ McAuliffe, Mary (15 December 2023). "You've heard of the Blueshirts but who were Ireland's Blue Blouses?". RTÉ Brainstorm. RTÉ. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Meet the Fascist Who Wanted to Become Ireland's Mussolini". 22 May 2021.

- ^ Maurice Manning, "The Blueshirts", Dublin, 1970

- ^ Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O'Duffy: A Self-Made Hero Archived 19 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, OUP Oxford, 2005, page 222

- ^ White, Martin. "THE GREENSHIRTS: FASCISM IN THE IRISH FREE STATE, 1935-45" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Ryan, Raymond (2005). "The Anti-Annuity Payment Campaign, 1934-6". Irish Historical Studies. 34 (135): 309. JSTOR 30008672.

- ^ "Eoin O'Duffy's Blueshirts and the Abyssinian crisis". History Ireland. 12 February 2013. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Irish Involvement in the Spanish Civil War 1936-39". rte.ie. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Manning, Maurice. "Dillon, James Mathew". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ MCCARTNEY, DONAL (16 October 1999). "A decent patriot". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Horgan, John (1 July 2021). "An Irishman's Diary on censorship and the Oireachtas". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ O'Shea, James (19 February 2016). "Blueshirts, Irish pro-fascist party, recalled in sale of rare uniform". Irish Central. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Farrell, Mel (September 2014). "From Cumann na nGaedheal to Fine Gael: The Foundation of the United Ireland Party in September 1933". Retrieved 6 January 2021.

This pattern is also replicated in popular memory of the period, with "Blueshirt" persisting as a pejorative term for supporters of Fine Gael up to the present day.

- ^ Farrell, Mel (26 May 2020). "Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil: 'Civil War' Parties?". Archived from the original on 10 May 2021.

The nature of 'Blueshirtism', 1933-36 remains a subject of controversy and there is unlikely to ever be a consensus as to what it constituted. While its growth in 1933 was linked to the Economic War, O'Duffy and other leading members were admirers of continental fascism. Most Blueshirts appear to have been motivated by a mixture of Civil War legacies and the controversies of the early 1930s

- ^ Stanley G. Payne, 'Fascism in Western Europe' in Walter Laqueur (ed.), Fascism: A Reader's Guide. Analyses, Interpretations, Bibliography (Pelican Books, 1979), p. 310.

- ^ Payne, p. 310.

- ^ McMahon, Cian (12 February 2013). "Eoin O'Duffy's Blueshirts and the Abyssinian crisis". Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ here Archived 31 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine and here Archived 19 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ O’Halpin, E. (1999). Defending Ireland: The Irish State and its Enemies since 1922. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820426-4.

- ^ Douglas, RM (December 2006). "The Pro-Axis Underground in Ireland, 1939-1942". The Historical Journal. 49 (4): 1155–1183. doi:10.1017/S0018246X06005772. JSTOR 4140154. S2CID 162641830. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

Although the Blueshirt phenomenon of the early 1930s had little in common with true fascism beyond what Maurice Manning has described as its 'liturgical' element

- ^ Cronin, Mike (1995). "The Blueshirt Movement, 1932-5: Ireland's Fascists?". Journal of Contemporary History. 30 (2): 311–332. doi:10.1177/002200949503000206. JSTOR 261053. S2CID 159632041. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Looby, Robert (February 2005). "Eoin O'Duffy – The Self-Made Hero. An interview with Dr. Fearghal McGarry". Three Monkeys Online. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ O’Flaherty, Eamon (Spring 2001). "RTÉ's 'Patriots to a Man', the Blueshirts & their times". Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Jackson, Alvin (1999). Ireland, 1798-1998. p. 300.

- ^ a b Newsinger, John (2001). "Blackshirts, blueshirts, and the Spanish Civil War". The Historical Journal. 44 (3): 825–844. doi:10.1017/S0018246X01002035.

- ^ FISCHER, JOACHIM (Spring 2012). "Review: A Murky World". The Irish Review (Cork). 44: 141–144. JSTOR 23350183. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ McGarry, Fearghal (22 September 2005). Eoin O'Duffy:A Self-Made Hero. OUP Oxford. p. 339. ISBN 9780199276554. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Douglas, RM (13 March 2013). "Ailtirí na hAiséirghe: Ireland's fascist New Order". Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ McNally, Frank (15 November 2015). "A man for all treasons – Frank McNally on a new book about Ernest Blythe: republican, fascist, and Orangeman". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Dorney, John (18 May 2012). "The Blueshirts – fascism in Ireland?". Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Eunan O'Halpin, Defending Ireland: The Irish State and its Enemies since 1922, (Oxford University Press, 1999) ISBN 0-19-820426-4.

- Mike Cronin, The Blueshirts and Irish Politics (The Four Courts Press Ltd, 1997) ISBN 1-851-82333-6

- Michael O'Riordan, Connolly Column, (New Books Dublin, 1979) ASIN: B0006E3ABG

- J. Bowyer Bell, The Secret Army: The IRA 1916-1979, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1983) ISBN 0-262-52090-7.

- Tim Pat Coogan, De Valera: Long Fellow, Long Shadow, (Arrow Publishing, 1995) ISBN 0-099-95860-0

- Michael Farrell, Northern Ireland: The Orange State (London: Pluto Press, 1980) ISBN 0-86104-300-6.

- F. S. L. Lyons, Ireland Since the Famine, (Fontana Press, 1985) 2nd ed., 2009, ISBN 0-007-33005-7

- Maurice Manning, The Blueshirts, (Gill & McMillan Ltd, 1971) ISBN 0-717-10502-4

- Keith Thompson, Irish Blueshirts. 2012. London: Steven Books. ISBN 9781-899435-74-6

- The Blueshirts - fascism in Ireland? The Irish Story

- Cian McMahon, The Blueshirts and the Abyssinian Crisis. History Ireland

- Donal O Driscoll, When Dev defaulted on the Land annuities. History Ireland

- Niall Cunningham, Eoin O'Duffy, Ireland's answer to Mussolini

- 'Before the Blueshirts - early Fianna Fáil and fascism', Mark Phelan, The Irish Times, 27 June 2016

- Fascism in Ireland

- 1932 establishments in Ireland

- 1933 disestablishments in Ireland

- Anti-communist organizations

- Catholicism and far-right politics

- Clothing in politics

- Conservatism in Ireland

- Far-right politics in Ireland

- Fine Gael

- Organisations based in the Irish Free State

- Organizations disestablished in 1933

- Organizations established in 1932

- Paramilitary organisations based in Ireland

- Fascist parties