Nancy Graves

Nancy Graves | |

|---|---|

Graves, c. 1959 | |

| Born | December 23, 1939 |

| Died | October 21, 1995 (aged 55) New York City, U.S. |

| Education | Vassar College, Yale University |

| Known for | Sculptor, Painter, Printmaker |

Nancy Graves (December 23, 1939 – October 21, 1995) was an American sculptor, painter, printmaker, and sometime filmmaker known for her focus on natural phenomena like camels or maps of the Moon. Her works are included in many public collections, including those of the National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.), the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Gallery of Australia (Canberra), the Des Moines Art Center, Walker Art Center (Minneapolis),[1] and the Museum of Fine Arts (St. Petersburg, FL).[2] When Graves was just 29, she was given a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. At the time she was the youngest artist, and fifth woman to achieve this honor.[3]

Early life and studies

[edit]Graves was born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Her interest in art, nature, and anthropology was fostered by her father, an accountant at the Berkshire Museum. After graduating from Vassar College in English Literature, Graves attended Yale University, where she received her bachelor's and master's degrees. Fellow Yale Art and Architecture alumni of the 1960s include the painters, photographers, and sculptors Brice Marden, Richard Serra, Chuck Close, Janet Fish, Gary Hudson, Rackstraw Downes, and Sylvia and Robert Mangold.[4]

After her graduation in 1964, she received a Fulbright Scholarship and studied painting in Paris. Continuing her international travels, she then moved on to Florence. During the rest of her life, she would also travel to Morocco, Germany, Canada, India, Nepal, Kashmir, Egypt, Peru, China, Australia.[5] She was married to Richard Serra from 1965 to 1970.[6]

Work

[edit]

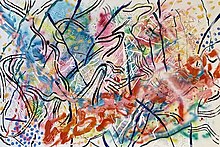

A prolific artist who worked in painting, sculpture, printmaking and film, Graves first made her presence felt on the New York art scene in the late 1960s and 70's, with life-size sculptures of camels that seemed as accurate as a natural history display. Like-minded artists included Eva Hesse, Close, Bruce Nauman, Keith Sonnier, and Serra, to whom Graves was married from 1965 to 1970.[7] Her work has strong ties to the Alexander Calder's stabiles and to the sculptures of David Smith, with their welded parts and found objects; she collected works by both artists.[5]

Her most famous sculpture, Camels, was first displayed in the Whitney Museum of American Art. The sculpture features three separate camels, each made of many materials, among them burlap, wax, fiberglass, and animal skin. Each camel is also painted with acrylics and oil colors to appear realistic. The camels are now stored in the National Gallery of Canada, and two later "siblings" reside in the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst in Aachen, Germany. Working in Fiberglas, latex, marble dust and other unorthodox materials, Graves later moved on to camel skeletons and bones, which she dispersed about the floor or hung from ceilings.[7] In Variability of Similar Forms (1970), from drawings that Graves made of Pleistocene camel skeletons, she sculpted 36 individual leg bones in various positions, each nearly the height of a man, and arranged them upright in an irregular pattern on a wooden base.[5] In the early 1970s, she made five films. Two of them, Goulimine, 1970 and Izy Boukir, recorded the movement of camels in Morocco, reflecting the influence of Eadweard Muybridge's motion-study photography.[5] In 1976, German art collector Peter Ludwig commissioned a wax variation of a 1969 sculpture of camel bones.

Graves began showing open-form polychrome sculptures in 1980, one prime example being Trace, a very large tree whose trunk was made from ribbons of bronze with foliage of steel mesh.[8] Also in the early 1980s, she began to produce the works for which she became most widely known: the colorfully painted, playfully disjunctive assemblages of found objects cast in bronze, including plants, mechanical parts, tools, architectural elements, food products and much more.[4]

Graves also created a distinctive body of aerial landscapes, mostly based on maps of the Moon and similar sources. Below is a link to an example (VI Maskeyne Da Region of the Moon). Author Margret Dreikausen (1985) writes extensively of Graves's aerial works as part of a broader discussion of the aerial view and its importance in modern and contemporary art.

Graves also began using the lost wax technique in her later work. She would cast delicate objects in bronze. Then use them to create arrangements. Her color scheme changed over time to bright colors in the 1980s and then shifted to more "subtle" colors in the 1990s.[9]

Some of Graves's other works include:

- Goulimine (film, 1970)

- Izy Boukir (film, 1971)

- VI Maskeyne Da Region of the Moon (lithograph, 1972)[10]

- Fragment (painting, 1977)[11]

- Wheelabout (sculpture, 1985)[12]

- Hindsight (sculpture, 1986)[13]

- Immovable Iconography (sculpture, 1990)[14]

- Footscray (oil on canvas, paint, and sculpture)

- Metaphore & Melanomy, (cast bronze, 1995)[15]

- Camels, VI, VII, VIII (wood, steel, burlap, polyurethane, wax, oil paint, 1969)[16]

- Fossils (Plaster, dust, marble dust, acrylic and steel, 1970)[16]

- Calipers (Hot-rolled steel, 1970)[16]

- Shaman (Latex on muslin, wax, steel, copper, aluminum wire, gauze, oil paint, marble dust, and acrylic, 1970)[16]

- Variability and Repetition of Similar Forms II (Bronze and COR-TEN steel, 1979)[16]

- Trambulate (Bronze and carbon steel with polyurethane paint and baked enamel, 1984)[16]

At the end of her life, Graves was incorporating handblown glass into her sculptures and experimenting with poly-optics, a glasslike material that can be cast.[7]

Graves worked and lived in Soho and in Beacon, New York, where she maintained a studio.[5]

Exhibitions

[edit]Graves, whose first New York exhibition was at the Graham Gallery in 1968, has been represented by M. Knoedler & Company since 1980. She exhibited extensively in galleries in the United States and Europe and is represented in museums around the world. A comprehensive museum retrospective, organized by the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, later traveled to the Brooklyn Museum in 1987.[7] When the restored Rainbow Room reopened in Manhattan's Rockefeller Center in 1987, a Graves sculpture was installed at the entrance.[5] A solo exhibition, "Nancy Graves: Mapping" was held at Mitchell-Innes & Nash in 2019.[17] Mitchell-Innes & Nash has represented the Estate of Nancy Graves since 2014.[18][19] The exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with an essay by Robert Storr.[20]

Awards

[edit]- Skowhegan Medal for Drawing/Graphics (1980)

- New York Dance and Performance Bessie Award (1986)

- Honorary Degree, Skidmore College (1989)

- Elected into the National Academy of Design (1992)

In others' art

[edit]Mary Beth Edelson's Some Living American Women Artists / Last Supper (1972) appropriated Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, with the heads of notable women artists collaged over the heads of Christ and his apostles. John the Baptist's head was replaced with Nancy Graves, and Christ's with Georgia O'Keeffe. This image, addressing the role of religious and art historical iconography in the subordination of women, became "one of the most iconic images of the feminist art movement."[21][22]

Death

[edit]Nancy Graves made her last works in April 1995 at the Walla Walla Foundry with Saff Tech Arts in Washington state.[15] In May, less than a month later, she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and died the following October, aged 55.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Entry for Nancy Graves on ArtCyclopedia

- ^ Pill, Katherine (2015). Marks Made. St. Petersburg, FL: Museum of FineArts. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-878390-15-8.

- ^ "It's Time to Rediscover Nancy Graves: Post-Minimalist, Anti-Pop Lover of Camels". Vogue. 28 February 2015. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- ^ a b Ken Johnson (March 11, 2005), Art in Review; Nancy Graves New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e f Cathleen McGuigan (December 6, 1987), Forms of Fantasy New York Times.

- ^ Roberta Smith (October 24, 1995), Nancy Graves, 54, Prolific Post-Minimalist Artist New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Roberta Smith (October 24, 1995), Nancy Graves, 54, Prolific Post-Minimalist Artist New York Times.

- ^ Grace Glueck (October 22, 1982), Art: Botanical Bronzes from Nancy Graves New York Times.

- ^ "Graves, Nancy | Grove Art". www.oxfordartonline.com. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T034150. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. Retrieved 2019-03-14.

- ^ VI Maskeyne Da Region of the Moon, Memorial Art Gallery, rochester.edu.

- ^ Fragment painting, Memorial Art Gallery, rochester.edu.

- ^ Wheelabout[permanent dead link] sculpture, themodern.org, Nancy Graves.

- ^ Hindsight Archived 2008-04-11 at the Wayback Machine sculpture, Walker Art Center.

- ^ Immovable Iconography sculpture, Nancy Graves, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art.

- ^ a b Walla Walla Foundry, Nancy Graves.

- ^ a b c d e f Linda, Nochlin (2015). Women artists : the Linda Nochlin reader. Reilly, Maura. New York, New York. ISBN 9780500239292. OCLC 892891670.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Nancy Graves - Exhibitions - Mitchell-Innes & Nash". www.miandn.com. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ "Nancy Graves gallery representation". Nancy Graves Foundation. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ "Mitchell-Innes & Nash Now Represents Nancy Graves Foundation, Shows Works on Paper at Frieze". Observer. 2014-05-09. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ "Nancy Graves - Exhibitions - Mitchell-Innes & Nash". www.miandn.com. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ "Mary Beth Edelson". The Frost Art Museum Drawing Project. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "Mary Beth Adelson". Clara - Database of Women Artists. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of Women in the Arts. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ "Biography at the Nancy Graves Foundation". Archived from the original on 2009-11-15. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

Further reading

[edit]- Dreikausen, Margret, "Aerial Perception: The Earth as Seen from Aircraft and Spacecraft and Its Influence on Contemporary Art" (Associated University Presses: Cranbury, New Jersey; London, England; Mississauga, Ontario: 1985) ISBN 0-87982-040-3.

- Graves, Nancy Stevenson; E A Carmean; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. The Sculpture of Nancy Graves: a catalogue raisonné with essays (New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Fort Worth Art Museum: Distributed in the United States … by Rizzoli International, ©1987) ISBN 0-933920-77-6; ISBN 0-933920-78-4.

External links

[edit]- 1939 births

- 1995 deaths

- 20th-century American painters

- Sculptors from Massachusetts

- Deaths from cancer in New York (state)

- Deaths from ovarian cancer in the United States

- People from Pittsfield, Massachusetts

- Yale School of Art alumni

- Art Students League of New York people

- Vassar College alumni

- 20th-century American sculptors

- 20th-century American women artists

- American women printmakers

- 20th-century American printmakers

- Sculptors from New York (state)

- Postminimalist artists

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters