Nidal Hasan

Nidal Hasan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Nidal Malik Hasan September 8, 1970[2] Arlington County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Education | |

| Occupation | Psychiatrist |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated on death row |

| Motive | Opposition to military deployment; Jihadism[1] |

| Conviction(s) |

|

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Details | |

| Date | November 5, 2009 ≈ 1:34–1:44 p.m. |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Texas |

| Location(s) | Fort Hood |

| Target(s) | U.S. Army soldiers and civilians |

| Killed | 13 |

| Injured | 32 |

| Weapons |

|

| Imprisoned at | United States Disciplinary Barracks |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States (until 2009) |

| Service | United States Army Medical Corps (until 2009) |

| Years of service | 1988–2009 (dismissal) |

| Rank | Major (revoked) |

| Awards | |

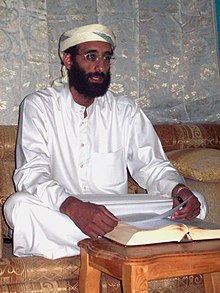

Nidal Malik Hasan (born September 8, 1970) is an American former United States Army major, physician and mass murderer convicted of killing 13 people and injuring more than 30 others in the Fort Hood mass shooting on November 5, 2009. [3] Hasan, an Army Medical Corps psychiatrist, admitted to the shootings at his court-martial in August 2013.[4][5]

During the six years Hasan was a medical intern and resident at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, concerns were raised about his job performance and behavior, specifically comments described by colleagues as "anti-American". Hasan was described as socially isolated, stressed by his work with soldiers, and upset about their accounts of warfare.[6] Two days before the shooting, less than a month before he was due to deploy to Afghanistan, Hasan gave away many of his belongings to a neighbor.[3][7][8]

Prior to the shooting, an investigation conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) concluded Hasan's email correspondence with the late Imam Anwar al-Awlaki were related to his authorized professional research and he was not a threat. The FBI, Department of Defense (DoD) and United States Senate all conducted investigations after the shootings.[9] The Senate released a report describing the shooting as "the worst terrorist attack on U.S. soil since September 11, 2001".[10][11]

Controversially, the Army decided not to charge Hasan with terrorism.[12] A jury panel of 13 officers convicted him of 13 counts of premeditated murder and 32 counts of attempted premeditated murder, and unanimously recommended he be dismissed from the service and sentenced to death.[13][14][15] Hasan is incarcerated at the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, awaiting execution.

Early life

[edit]Nidal Hasan was born on September 8, 1970, at Virginia Hospital Center in Arlington County, Virginia. His parents were naturalized American citizens of Palestinian origin; they had immigrated years earlier from al-Bireh, a city in the West Bank near Jerusalem.[16][17][18][19]

Raised in the Muslim faith with his two younger brothers, Hasan attended Wakefield High School in Arlington for his freshman year in 1985. His family moved to Roanoke in 1986, where his father had moved a year prior to set up what would become a number of successful family-owned businesses which included a market, restaurant and olive bar.[20]

Hasan graduated from Roanoke's William Fleming High School in 1988.[21][22] His father died in 1998 at the age of 51; his mother died three years later at the age of 49.[22] One of his brothers continues to live in Virginia while the other moved to the Palestinian Territories.[17]

Military service, higher education and medical career

[edit]Hasan enlisted in the United States Army in 1988 after graduating from high school. He attended college during this time, earning an associate degree in science from Virginia Western Community College in 1992. In 1995, he graduated from Virginia Tech with a bachelor's degree in biochemistry. He completed both of these programs with Latin honors.[23] He was commissioned as an officer in the Army Medical Department in 1997, and enrolled at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) in Bethesda, Maryland.[20]

Hasan's performance was marginal while enrolled at USUHS. He was on academic probation during much of the six years he required to complete the four-year curriculum and graduate medical school.[24] Upon graduation in 2003, Hasan completed his internship and residency in psychiatry at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC). He completed his psychiatry training with a two-year fellowship in disaster and preventive psychiatry, earning a master's degree in public health. During his training at Walter Reed, he received counseling and extra supervision.[25]

According to The Washington Post, Hasan made a presentation titled "The Quranic World View as It Relates to Muslims in the U.S. Military" during his senior year of residency at WRAMC; it was not well received by some attendees.[26] He suggested the U.S. Department of Defense "should allow Muslims [sic] Soldiers the option of being released as 'Conscientious objectors' to increase troop morale and decrease adverse events."[27][28] On a previous slide, he explained "adverse events" could be refusal to deploy, espionage, or killing of fellow soldiers.

Retired Colonel Terry Lee, after working with Hasan, recalled[29] the fatal shooting of two recruiters in Little Rock, Arkansas, greatly affected Hasan. Lee told Fox News that Hasan made "outlandish" statements against the American military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan, reportedly saying that "the Muslims should stand up and fight against the aggressor", referring to American soldiers. Hasan expressed hope U.S. President Barack Obama would withdraw troops. He was frequently agitated and argumentative with other Army personnel.[30][31]

Despite these problems, in May 2009, Hasan was promoted to major.[20] In July 2009 he was transferred to Darnall Army Medical Center in Fort Cavazos (then Fort Hood), Texas, moving into the city of Killeen. Two weeks later, he lawfully purchased an FN Five-seven handgun.[20] Prior to his transfer, Hasan had received a 'poor performance' evaluation from supervisors and medical faculty.[32] Despite concerns, his former boss, Lt. Col. Ben Phillips, graded his performance as "outstanding".[33]

Hasan's cousin, Virginia attorney Nader Hasan, disputed the assertion that he was "disenchanted with the military," but said Hasan dreaded war after counseling soldiers with post-traumatic stress disorder. He was "mortified by the idea" of deploying after he heard on a "daily basis the horrors they saw over there". Nader also stated Hasan was harassed by his fellow soldiers. "He hired a military attorney to try to have the issue resolved, pay back the government, to get out of the military. He was at the end of trying everything."[34] Hasan's aunt also said Hasan sought discharge because of harassment relating to his Islamic faith.[23] However, an Army spokesman did not confirm the relatives' statements;[35] with the deputy director of the American Muslim Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs Council stating the reported harassment was "inconsistent" with their records.[36]

Hasan's uncle Rafiq Hamad, a resident of Ramallah in the West Bank, characterized Hasan as gentle and quiet. He fainted while observing childbirth, whence his choice to focus on psychiatry. He was deeply sensitive, and mourned a pet bird for months after it died.[25] Also near Ramallah, cousin Mohammed Hasan said "because he's Muslim, he didn't want to go to Afghanistan or Iraq, and he didn't want to expose himself to violence and death". Mohammed stated his cousin was a "pleasant young man" who was happy to graduate and to be joining the army after his uncle and cousins served. They never talked about politics, but Hasan complained "he was treated like a Muslim, like an Arab, rather than an American; he was discriminated against."[37]

In August 2009, according to a Killeen police report, someone vandalized Hasan's automobile with a key; repair was estimated at $1000. Police charged a soldier; a neighbor claimed the vehicle was vandalized because of Hasan's religion.[23]

According to military records, Hasan was unmarried.[38] However, David Cook, a former neighbor, stated, in 1997, Hasan had two sons living with him and attending local schools. Cook said, "As far as I know, he was a single father. I never saw a wife."[18]

Military awards and decorations

[edit]Hasan received the Army Service Ribbon as a private in 1988 after completing Advanced Individual Training (AIT), the National Defense Service Medal twice for service during the time periods of the Persian Gulf War and the Global War on Terror, and the Global War on Terrorism Service Medal for support service during the Global War on Terror.[7]

Religious and ideological beliefs

[edit]According to one of his cousins, Hasan was Muslim; he became more devout after the early deaths of his parents.[17] His cousin did not recall him expressing any radical or anti-American views,[17] and his family also described Hasan as a peaceful person, and a good American.[39] One of his cousins said Hasan turned against the wars after hearing the stories of soldiers he treated in therapy following their return from Afghanistan and Iraq.[40] His aunt said he did not tell the family he was going to Afghanistan.[41]

In May 2001, Hasan attended the Dar Al-Hijrah mosque in the Falls Church area for the funeral of his mother[42] and occasionally, attended a mosque in Silver Spring, Maryland, close to where he lived and worked; he was well-known by the Imam for over a decade.[43] Faizul Khan, the former Imam of the Silver Spring mosque where Hasan prayed several times a week, said he was "a reserved guy with a nice personality. We discussed religious matters. Politics were never brought up. He is Muslim."[18] Khan said Hasan often expressed his wish to get married, and the Imam said, "I got the impression he was a committed soldier."[23]

Air Force Lt. Col. Dr. Val Finnell, a graduate school classmate in the Master's in Public Health program, said in a class on environmental health, Hasan's project dealt with "whether the Global War On Terror is a war on Islam" and the effect on Muslims in the military, which Finnell thought was strange.[44]

According to Colonel Terry Lee, since retired, "He [Hasan] said 'maybe Muslims should stand up and fight against the aggressor'. At first, we thought he meant help the armed forces, but apparently that wasn't the case. Other times, he said we shouldn't be in the war in the first place."[45]

Email exchanges with Anwar Al-Awlaki

[edit]In 2001–02, Anwar al-Awlaki was the Imam of the Dar al-Hijrah mosque; during that time, he was considered a moderate Muslim. Serving as the Muslim chaplain at George Washington University, he was frequently invited to speak about Islam to audiences in Washington DC and to members of Congress and the government. Hasan reportedly had deep respect for al-Awlaki's teachings.[46]

Eleven months prior to the shootings, in December 2008, federal intelligence officials captured a series of e-mail exchanges between Al-Awlaki and Hasan. During this period, al-Awlaki was deemed a "radical cleric". However, they determined the e-mails were religious, and did not contain any elements of militancy nor any concerning subject matter.[20] Counter-terrorism specialists for the FBI reading the e-mails stated "they were consistent with authorized research Major Hasan was conducting."[47][48][49] The e-mails contained general questions about spiritual guidance with regard to conflicts between Islam and military service, and officials judged them to be consistent with his legitimate mental health research about Muslims in the American armed services.[50][51][52]

After the shootings, the Yemeni journalist Abdulelah Hider Shaea interviewed al-Awlaki in November 2009 about their exchanges, and discussed their time with a Washington Post reporter. According to Shaea, Al-Awlaki said he "neither ordered nor pressured ... Hasan to harm Americans".[53] Al-Awlaki said Hasan first e-mailed him on December 17, 2008. By way of introduction, Hasan said: "Do you remember me? I used to pray with you at the Virginia mosque."[53] According to Al-Awlaki, Hasan said he was Muslim around the time the Imam was preaching at Dar al-Hijrah in 2001 and 2002. This coincides with the death of his mother.

Al-Awlaki said, "Maybe Nidal was affected by one of my lectures." He added: "It was clear, from his e-mails, Nidal trusted me. Nidal told me: 'I speak with you about issues I never speak with anyone.'" Al-Awlaki said Hasan arrived at his conclusions regarding the acceptability of violence in Islam, and said he was not the one to initiate this. Shaea summarized their relationship by saying, "Nidal was providing evidence to Anwar, not vice versa."[53]

In October 2008, Charles Allen, US Undersecretary of Homeland Security for Intelligence and Analysis, warned al-Awlaki "targets US Muslims with radical online lectures encouraging terrorist attacks from his new home in Yemen".[54][55]

Former CIA officer Bruce Riedel says "E-mailing a known al-Qaeda sympathizer should set-off alarm bells. Even if he was exchanging recipes, the bureau should have put out an alert."[56]

Al-Awlaki had a website with a blog to share his views.[56] On December 11, 2008, he condemned any Muslim who seeks a religious decree "that would allow him to serve in the armies of the dis-believers and fight against his brothers."[56] The NEFA Foundation says, on December 23, 2008, six days after he said Hasan first e-mailed him, al-Awlaki wrote on his blog: "The bullets of the fighters of Afghanistan and Iraq are a reflection of the feelings of Muslims toward America."[57]

An unidentified Muslim officer at Fort Hood said Hasan's eyes "lit up" while speaking about al-Awlaki's teachings.[58] Some investigators believe Hasan's contacts with al-Awlaki pushed him toward violence at a time he was depressed and stressed.[59]

Prior to the Fort Hood shooting

[edit]Internet activity

[edit]The government agents monitoring Islamic websites believe Hasan, using the screenname 'NidalHasan', posted about suicide bombings in May 2009, although, during this period, government agents did not link the posts to Hasan.[44][60] The postings by 'NidalHasan' likened a suicide bomber to a soldier falling on a grenade to save his colleagues, to sacrifice for a "noble cause".[44][60] ABC News reported after the fact, anonymous government agents issued a press-release claiming they were allegedly aware Hasan attempted to contact Al Qaeda,[61] then issued a press-release claiming Hasan had "more unexplained connections to people tracked by the FBI" than just Anwar al-Awlaki.[62]

Hasan's business card left in his apartment describes him as a psychiatrist specializing in Behavioral Health – Mental Health – Life Skills, and contains the acronyms SoA (SWT).[63][64][65] According to investigators, the acronym "SoA" is used on jihadist websites as an acronym for "Soldier of Allah" or "Servant of Allah." SWT is commonly used to mean "subhanahu wa ta'ala" (Glory to God).[47][66] A review of Hasan's computer and e-mail accounts show visits to Internet sites espousing radical Islamist ideas, according to a press-release from an anonymous government agent.[67]

Emails to superiors

[edit]Hasan expressed concern about the former actions by some of the soldiers he evaluated as a psychiatrist.[68] Days before his attacks on Fort Hood in 2009, Hasan asked his supervisors and Army legal advisers how to handle reports of soldiers' deeds in Afghanistan and Iraq that disturbed him.[68]

Other activity

[edit]Hasan was to be deployed to Afghanistan[69] on November 28. Hasan told a local store owner he was stressed about his imminent deployment to Afghanistan since his work as a psychologist might require him to fight or kill fellow Muslims.[70] In a press-release from Jeff Sadoski, spokesman for U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, "Hasan was upset about his deployment".[71]

Hasan gave away furniture from his home on the morning of the shooting, saying he was going to be deployed on Friday.[72] He also distributed copies of the Quran.[73] Kamran Pasha wrote about a Muslim officer at Fort Hood who said he prayed with Hasan on the day of the Fort Hood shooting, and Hasan "appeared relaxed and not in any way troubled or nervous". This officer believed the shootings could possibly be motivated by religious radicalism.[20][74]

Fort Hood attacks

[edit]

On November 5, 2009, Hasan reportedly shouted "Allahu Akbar!"[75][76][77] (the phrase means "God is great"),[78][79] and opened fire on armed forces in the Soldier Readiness Center of Fort Hood, located in Killeen, Texas, killing thirteen people and wounding over thirty others in the worst shooting against armed forces on an American military base.[8]

Department of the Army police officer Kimberly D. Munley encountered Hasan leaving the building. Munley and Hasan exchanged shots before Munley was shot in the leg twice.[80] Department of the Army police officer Mark Todd shot Hasan several times.[81][82] Todd kicked the pistol out of Hasan's hand, then cuffed Hasan.[83] The attack lasted about ten minutes.[84]

Post-shooting

[edit]Medical condition

[edit]To save his life, Hasan was hospitalized in the intensive care unit at Brooke Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas.[85][86] His condition was described as "stable".[87] News reports on November 7, 2009, indicated he was in a coma.[88] On November 9, hospital spokesperson Dewey Mitchell announced Hasan regained consciousness, and was able to talk since he was removed from a ventilator on November 7.[89] On November 13, Hasan's attorney, John Galligan, announced Hasan was paralyzed from the waist down from the bullet wounds to his spine, and would likely never walk.[90] In mid-December, Galligan indicated Hasan was moved from intensive care to a private hospital room. Galligan said doctors indicated Hasan would need at least two months in the hospital to learn "to care for himself".[91]

Court-martial

[edit]On November 7, 2009, while Hasan was communicative, he refused to talk to law enforcement officials.[92] On November 12 and December 2, respectively, Hasan was charged with thirteen counts of pre-meditated murder and thirty-two counts of attempted murder under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, thus making him eligible for the death penalty.[14][15][93]

At the time, authorities did not specify if they would seek the death penalty,[94] Colonel Michael Mulligan would serve as the Army's lead prosecutor. Mulligan was lead prosecutor on the Hasan Akbar case, in which a soldier was sentenced to death for the murder of two members of the US military.[95]

John P. Galligan, a retired Army JAG colonel, represented Hasan.[96] On November 21, in a hearing held in Hasan's hospital room, a military magistrate ruled there was probable cause Hasan committed the shooting spree at Fort Hood, and ordered pre-trial confinement until his court-martial. Hasan remained in intensive care in accordance with the magistrate's dictate.[97] On November 23, Galligan said Hasan would likely plead not guilty to the charges against him, and may use an insanity defense at his court-martial.[98] In a press-release, Army public affairs staff stated doctors would evaluate Hasan by mid-January 2010 to determine his competency to stand trial as well as his mental state at the time of the attacks,[95] but delayed the exam on request from Galligan until after the Article 32 hearing.[99] The Army dictated Hasan speak only in English on the phone or with visitors unless an interpreter was present.[100] Hasan was moved from Brooke Army Medical Center to the Bell County Jail in Belton, Texas, on April 9, 2010.[101] Fort Hood negotiated a renewable $207,000 contract with Bell County in March to house Hasan for six months.[102]

In a press release, Galligan announced prosecutors would seek the death penalty, stating, "It is the first 'formal notice' but, of course, it is a virtual given from the start. In short, the Army has been pursuing death from the git-go."[103] The prosecutors filed a memo on April 28, 2010, stating the "aggravating factor" necessary for pursuit of the death penalty will be satisfied if Hasan is found guilty of more than one murder.[103] The decision to seek the death penalty followed the Article 32 hearing.[103] In a September 15, 2010, press release, Hasan's attorney stated he intended to seek closed court hearings.[104]

On October 12, 2010, Hasan was due to appear for his first broad military hearing into the attack. The hearing, formally called an Article 32 proceeding, akin to a grand jury hearing but open to the public, was expected to span six weeks. The hearing, designed to help the top Army commander at Ft. Hood determine whether there was enough evidence to court-martial Hasan, was scheduled to begin calling witnesses, but was delayed by technicality disputes.[105] The hearing proceeded on October 14 with witness testimonies from survivors of the attacks.[106] On November 15, the military hearing ended after Galligan declined to offer a defense case, on the grounds the White House and Defense Department refused to release documents he requested pertaining to an intelligence review of the shootings. Neither the defense nor prosecution offered to deliver a closing argument.[107]

On November 18, Colonel James L. Pohl, investigating officer for the Article 32 hearing, recommended Hasan be court-martialed and face the death penalty. His recommendation was forwarded to another U.S. Army colonel at Fort Hood, who, after filing his report, presented his recommendation to the post commander. The post commander decided Hasan would face a trial and the death penalty.[108] On July 6, 2011, the Fort Hood post commander referred the case to a general court-martial authorized to consider the death penalty.[109] On July 27, 2011, Fort Hood Chief Circuit Judge Colonel Gregory Gross set a March 5, 2012, trial date. Hasan declined to enter any plea, and Judge Gross granted a request by Hasan's attorneys to defer the plea. Hasan notified Gross he had released John Galligan, his civilian attorney during previous court appearances, choosing to be represented by three military lawyers.[110]

On February 2, 2012, a military judge delayed the trial until June 12, 2012. Lieutenant Colonel Kris Poppe, Hasan's lead attorney, said the request to delay the trial was "purely a matter of necessity of adequate time for pre-trial preparation".[111]

On April 10, 2012, Hasan's lawyers requested another continuance to move the trial start date from June to late October to investigate paperwork and evidence and interview witnesses. Gross agreed to take the request under advisement. Judge Gross denied a defense motion seeking a Defense Initiated Victim Outreach specialist to testify, Fort Hood officials said. The new program is intended to help the defense respond to the needs of survivors and victims' families, and possibly change their attitudes if they support the death penalty. Gross also denied a defense request to force prosecutors to provide notes from meetings and conversations with President Barack Obama, the defense secretary, and other government agents after the November 5, 2009, attacks. Defense attorneys argued they want to determine if anything unlawfully influenced Hasan's chain of command to prosecute him. On April 18, 2012, Judge Gross granted in part the defense motion for a continuance, scheduling the trial for August 20, 2012.[112]

In July 2012, after dictating Hasan shave his beard, the judge found Hasan in contempt of court and fined him.[113] He was fined once more for retaining his beard, and was warned by Judge Colonel Gregory Gross he could be force-shaved prior to his court-martial.[114] On August 15, Hasan was scheduled to enter pleas to the charges brought against him before the beginning of the court-martial; he would not be allowed to plead guilty for the premeditated murder charges because prosecutors pursued the death penalty.[115]

The court-martial was delayed by Hasan's objections to being shaved against his will, and his appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces regarding the matter; through his attorneys, Hasan said his beard is part of his religious beliefs. The prosecutors argued Hasan was simply trying to delay his trial.[116]

On August 27, the Appeals Court announced the trial could continue, but did not rule whether Hasan could be force-shaved nor did they set a new date for the start of the trial. The Appeals Court rejected attempts by Hasan to receive "religious accommodation" to grow a beard.[117] On September 6, Colonel Gross ruled Hasan be force-shaved after he determined the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act did not apply to this case; however, the force-shave will not be enforced until Hasan's appeals are exhausted.[118][119] During the September 6 hearing, Hasan twice offered to plead guilty; however, U.S. Army rules prohibit judges from accepting a guilty plea in a death penalty case.[119]

Hasan remained incarcerated and in a wheelchair. He continued to receive paychecks.[120]

On June 3, 2013, a military judge allowed Hasan to represent himself. His attorneys were to remain on the case, but only if he asked for their help. Jury selection was set to start on June 5, and opening arguments were scheduled to begin on July 1.[121][122] On June 14, 2013, U.S. Army Colonel Tara Osborn dictated Hasan could not claim he was defending the Taliban.[123] In a press-release, Hasan justified his actions during the Fort Hood attacks by claiming the US military was at war against Islam.[124]

During the first day of the trial on August 6, Hasan, representing himself, admitted he was the attacker during the Fort Hood attacks in 2009, and stated the evidence would show he was the attacker. He also told the panel hearing he "switched sides", and regarded himself as a Mujahideen waging "jihad"—waging war—against the US military.[125] By August 7, disagreements between Hasan and his stand-by defense team led Judge Osborn to suspend the trial. Hasan's defense attorneys were concerned Hasan was trying to help prosecutors achieve a death sentence. Because the prosecutors sought the death penalty, his defense team sought to prevent this.[126]

On August 8, Judge Osborn ruled Hasan could continue to represent himself during the trial, then rejected his stand-by defense team's requests they take over Hasan's defense or have their roles reduced. The judge also declined the defense lawyers' request they be removed from the case. On August 9, Hasan allowed two of his three stand-by defense lawyers—Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Martin and Major Joseph Marcee—to seek leave to prepare an appeal arguing the defendant was seeking the death penalty, thus undermining their rules of "professional conduct".[127][128] His third attorney Lieutenant Colonel Kris Poppe remained behind to observe the court proceedings.[129] Court proceedings also resumed with the prosecution presenting testimonies from several survivors of the Fort Hood attacks. By August 14, more than sixty prosecution witnesses testified, and each identified Hasan as the attacker. Court proceedings were speedy because Hasan raised few objections and declined to cross-examine most witnesses.[130]

By August 13, prosecutors shifted to presenting forensic evidence with FBI agents present at the crime scene testifying they had so much evidence at the crime scene, they ran out of markers. This evidence included one hundred forty-six cartridge cases and six magazines. The New York Times published remarks by Hasan from a mental health report supplied by the defendant's civil attorney John Galligan. According to these documents, Hasan told mental health professionals he "would still be a martyr" if he was convicted and executed.[131] Hasan, acting as his defense lawyer, offered to share the report with prosecutors during his court-martial. However, on August 14, Judge Osborn blocked prosecutors from seeing the report.[132] On August 19, she also excluded prosecuting evidence relating to Hasan's early radicalization, plus evidence which presented the Fort Hood attacks as a "copycat" based on the actions of Hasan Akbar, U.S. Army soldier sentenced to death.[133]

On August 20, 2013, prosecutors rested their case against Hasan. They called nearly ninety witnesses over eleven days with the fast pace of proceedings attributed to Hasan's refusal to cross-examine most witnesses. Throughout the proceedings, he only questioned three witnesses. While the defense was scheduled to present his case on Wednesday, Hasan indicated he had no plans to call any defense witnesses. Earlier, he planned to call two defense witnesses: one a mitigation expert in capital murder cases, and the other a California university professor specializing in philosophy and religion. Hasan also formally declined to argue prosecutors failed to prove their case.[134][135] Hasan did not call any witnesses or testify in his defense; he rested his defense on August 21, 2013.[136] On August 22, 2013, Hasan declined to give a closing argument.[137]

Verdict and sentencing

[edit]On August 23, 2013, the military jury consisting of nine colonels, three lieutenant colonels, and one major[138] convicted Hasan of all charges, making him eligible for the death penalty.[139] Those deliberations began on August 26, 2013.[140] By August 27, the thirteen-member panel of jurors heard testimony from twenty-four victims and family members of those wounded and killed during the 2009 Fort Hood attacks against American armed forces.[141] Throughout the proceedings, Hasan declined to speak in his defense or question any of the witnesses. He also did not provide any material explaining his decision to not mount a defense throughout the trial and sentencing. At the end, Hasan, acting as his attorney, told jurors the defense rested his case. Judge Tara Osborn accepted Hasan's decision. In his final statement, lead prosecutor Colonel Mike Mulligan said

[Hasan] can never be a martyr because he has nothing to give ... Do not be misled; do not be confused; do not be fooled. He is not giving his life. We are taking his life. This is not his gift to God, it's his debt to society. He will not now and will not ever be a martyr.[142]

The jurors re-convened to decide sentencing.[143][144] On August 28, 2013, the jurors recommended Hasan be sentenced to death.[145] The panel also recommended Hasan forfeit his military pay and be dismissed from the Army, a separation for officers carrying the same consequences as a dishonorable discharge.[146] Due to mandatory appeals and the military's historical reluctance to execute convicts, any execution is years away.[147]

Reaction

[edit]Praise from Islamic extremists

[edit]Some Muslims claimed the events in Islamist terms for political purposes. After the Fort Hood attacks, Anwar al-Awlaki praised Hasan's actions:[148]

Nidal Hassan [sic] is a hero. He is a man of conscience who could not bear living the contradiction of being a Muslim and serving in an army fighting against his people [...] Any decent Muslim cannot live, understanding properly his duties toward his Creator and his fellow Muslims, and yet serve as a member of the US armed forces. The U.S. is leading the war against terrorism which, in reality, is a war against Islam.[149][150]

Al-Awlaki posted this as part of a lengthy Internet message.[151]

In March 2010, Al Qaeda spokesman Adam Yahiye Gadahn praised Hasan, saying, although he was not a member of Al Qaeda, the

Mujahid brother [...] shown us what one righteous Muslim with an assault rifle [sic] can do for his religion and brothers in faith [...] is a pioneer, a trail-blazer, and a role-model [...] and yearns to discharge his duty to Allah and play a part in the defense of Muslims against the savage, heartless, and bloody Zionist Crusader assault on our religion, sacred places, and homelands.[152]

Hours before the attacks, CNN posted an interview and video of a New York city organization called Revolution Muslim, in which Younes Abdullah Mohammed (a Jew converted to Islam) spoke outside a New York mosque, saying U.S. armed forces are "legitimate targets", and Osama bin Laden was their model. The evening after the attacks, Revolution Muslim posted support for Hasan on their website, one of the few American sites to do so. In the video, RM described American armed forces as "slain terrorists in the eternal hellfire".[153] Some Muslims condemned the organization.[153][154]

A November 2009 press-release from the Ansar Al-Mujahideen Network cited Hasan as a role model. They congratulated him for his "brave and heroic deed" for standing up to the "modern Zionist-Christian Crusades" against Muslims.[153]

Retrospective analyses

[edit]Selena Coppa, an activist opposed to the U.S. occupation of Iraq, said: "This man was a mental health professional and was working with other mental health professionals every day, and they failed to notice how deeply-disturbed someone right in their midst was."[155]

Hasan's perceived beliefs were also a cause for concern among some of his peers. According to an anonymous source, Hasan was disciplined for "proselytizing about his Muslim faith with patients and colleagues" while at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS).[156] The Telegraph reported an incident in which some attendees felt that one of his lectures, expected to be of a medical nature, became a diatribe against "infidels". Air Force doctor Val Finnell, a former medical school classmate, complained to superiors about Hasan's "anti-American rants". Finnell said: "The system is not doing what it's supposed to do. He at least should have been confronted about these beliefs, told to cease and desist, and to shape up or ship out."[155]

Jarret Brachman, a scholar of terrorism, said Hasan's contacts with al-Awlaki raised "huge red flags". According to Brachman, al-Awlaki is a major influence internationally on English-speaking jihadists.[157]

The Dallas Morning News reported on November 17 that law enforcement officials suspected the attacks were triggered by the refusal of Hasan's superiors to process his requests seeking to have some of his patients prosecuted for war crimes based on statements they made during psychiatric sessions with him. Dallas attorney Patrick McLain, a former Marine, opined that Hasan was lawfully justified in sharing privileged information from his patients, but it was impossible to be sure without knowing that information. Some fellow psychiatrists complained to superiors Hasan's requests violated physician–patient privilege.[158]

Shortly after the attacks, General George Casey, Chief of Staff of the Army, said the "real tragedy" would be harming the cause of diversity, saying, "As great a tragedy as this was, it would be a shame if our diversity became a casualty as well."[159] Several months later, in a February 2010 interview, Casey said, "Our diversity—not only in our Army, but in our country, is a strength. And as horrific as this tragedy was, if our diversity becomes a casualty, I think that's worse."[160]

FBI Director Robert Mueller appointed William Webster, a former director of the FBI, to conduct an independent review of the bureau's handling of investigations related to Hasan and whether they missed indicators of an attack. Webster was selected for the job due to, as Mueller stated, being "uniquely qualified" for such a review,[161] and the Webster Commission's press-release includes several recommendations including written policies to "[...] clarify the ownership of leads, integration of databases, and acquiring search capabilities for all relevant databases based on computational analysis of textual data to replace simple keyword searches [...]".[162]

Media analysis and political statements

[edit]On the November 9, 2009, Fox News Sunday show, U.S. Senator Joe Lieberman called for a probe by his Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. In his press-release, Lieberman said,

if the reports we're receiving of various statements he made, acts he took, are valid, he turned to Islamist extremism [...] if that is true, the murder of these thirteen people was a terrorist act [...] I think it's very important to let the Army and the FBI go forward with this investigation before we reach any conclusions.[163][164]

The November 23 cover of the European and U.S. editions of Time magazine featured a photograph of Hasan, with the title "Terrorist?" over his eyes.[165] Nancy Gibbs reported the cover story: "Hasan matched the classic model of the lone, strange, crazy killer: the quiet and gentle man who formed few close human attachments."[166] She noted, "Hasan's motives were mixed enough that everyone with an agenda could find markers in the trail he left."[166] Bruce Hoffman, a terrorism scholar and Georgetown University professor, told Gibbs "I used to argue it was only terrorism if it were part of some identifiable organized conspiracy [...] the nature of terrorism is changing, and Major Hasan may be an example of that".[166] The Christian Science Monitor also questioned whether Hasan was a terrorist.[167]

On November 14, The New York Times stated, "Major Hasan may be the latest example of an increasingly common type of terrorist, self-radicalized with the help of the Internet, and wreaks havoc without support from overseas networks and without having to cross a border to reach his target."[168]

Prison life

[edit]Following his conviction and sentencing, Nidal Hasan was incarcerated at the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas to await execution. According to Chris Haug, Fort Hood's Chief of Media Relations, Hasan was stripped of his rank and dismissed from the U.S. Army.[13] Hasan would only be referred to as "Inmate Nidal Hasan" going forward.[13] On September 5, 2013, prison staff force-shaved Hasan. Fort Leavenworth authorities justified their decision by citing Hasan would be subject to Army regulations although he was dismissed from the Army and forfeited all pay and allowances. Despite Army regulations banning personnel from facial hair, Hasan stopped shaving following the Fort Hood attacks in 2009 by citing his religious beliefs.[169][170] Although no new photos of Hasan have been released since his incarceration, military authorities confirmed that a video recording of the force-shaving exists, as per military regulations. In response, John Galligan, Hasan's former civilian lawyer, planned to sue the military for violating his religious beliefs. Galligan argued a military council in 2012 allowed Hasan to keep his beard for the duration of the trial, and dismissed the Army's actions as vindictive.[171]

On August 28, 2014, Hasan's attorney said Hasan wrote to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, then head of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). In the letter, Hasan requested to be made a citizen of the Islamic State, and included his signature and the abbreviation SoA (Soldier of Allah).[172][173]

In popular culture

[edit]The Israeli singer Eric Berman, in his album "Oh Pathetic Ridiculous Heart," composed the song "Not A Simple Story" following the background of the attacks. The song describes Hasan's biography and his deterioration leading him to attack.[174][175][176]

See also

[edit]- Capital punishment by the United States military

- Jihobbyist

- List of mass shootings in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ Hasan testified at his court-martial that he had "switched sides" and regarded himself as a Mujahideen waging "jihad" against the United States. Allen, Nick (August 6, 2013). "'I am the shooter': US army major Nidal Hasan declares as he faces court martial over Fort Hood massacre". The Daily Telegraph. London. The Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ James C. McKinley Jr.; James Dao (November 8, 2009). "Fort Hood Gunman Gave Signals Before His Rampage". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ a b McKinley, James C. Jr.; Dao, James (November 8, 2009). "Fort Hood Gunman Gave Signals Before His Rampage". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ Rubin, Josh (August 6, 2013). "'I am the shooter,' Nidal Hasan tells Fort Hood court-martial". CNN. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ "Army releases May officer promotions". Military Times. April 22, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Brady, Jeff (November 11, 2009). "Portrait Emerges Of Hasan As Troubled Man". NPR. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ a b "Maj. Nidal M. Hasan's Official Military Record". Newsweek. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ a b "Lawmakers' briefing causes confusion on wounded". The Seattle Times. The Seattle Times Company. Associated Press. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013.

- ^ Jervis, Rick; Stanglin, Doug (August 23, 2013). "Nidal Hasan found guilty in Fort Hood killings". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ^ Pike, John. "A Ticking Time Bomb: Counterterrorism Lessons from the U.S. Government's Failure to Prevent the Fort Hood Attack". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ Heather Somerville (February 3, 2011). "Opinion: Fort Hood attack: Did Army ignore red flags out of political correctness?". The Christian Science Monitor. Christian Science Publishing Society. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ Myers, Dee Dee (November 11, 2009). "Is Nidal Hasan a Terrorist or Not?". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c Janda, Greg (September 5, 2013). "Fort Hood shooter Nidal Hasan dishonorably discharged, no longer major". NBCDFW. Archived from the original on September 9, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ^ a b McKinley, James Jr. (November 12, 2009). "Suspect in Fort Hood Attack Is Charged on 13 Murder Counts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "Army adds charges against rampage suspect". NBC News. December 2, 2009. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- ^ Friedman, Emily; Richard Esposito; Ethan Nelson; Desiree Adib; Ammu Kannampilly (November 6, 2009). "Army Doctor Nidal Malik Hasan Allegedly Kills 13 at Fort Hood". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 30, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Dao, James (November 5, 2009). "Suspect Was 'Mortified' About Deployment". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ a b c Casselman, Ben; Zimmerman, Ann; Bustillo, Miguel (November 6, 2009). "A Helper With Worries of His Own". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Profile: Major Nidal Malik Hasan". BBC. November 12, 2009. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Bennett, Kitty; Times, Sarah Wheaton/The New York. "The Life and Career of Major Hasan". www.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ "Maj. Nidal M. Hasan". The Washington Post. November 7, 2009. Archived from the original on November 10, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Hammack, Laurence; Amanda Codispoti; Tonia Moxley (November 7, 2009). "Fort Hood shooting suspect Hasan left few impressions in schools he attended". The Roanoke Times. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Blackledge, Brett J. (November 6, 2009). "Who is Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan?". Fox News. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ Mount, Mike. "Military review: Troubling signals from Fort Hood suspect missed". CNN. Archived from the original on March 25, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Mckinley, James C.; DAO, James (November 8, 2009). "Fort Hood Gunman Gave Signals Before His Rampage". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ "The Quranic World View As It Relates to Muslims in the U.S. Military" (PDF). NEFA Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ Priest, Dana (November 10, 2009). "Fort Hood suspect warned of threats within the ranks". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 28, 2010. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ Hasan, Nidal (November 10, 2009). "Hasan on Islam". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 19, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ "Major Nidal Malik Hasan: Soldiers' psychiatrist who heard front-line stories" Archived March 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Ewen MacAskill, The Guardian, November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Fox video: Fight against the aggressor". Fox News. May 1, 2011. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ^ Officials Begin Putting Shooting Pieces Together Archived September 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, NPR, November 6, 2009.

- ^ "BBC News, Profile: Major Nidal Malik Hasan, October 12, 2010". BBC News. October 12, 2010. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Fort Hood trial turns bizarre as shooter grills witnesses". Foxnews.com. August 6, 2013. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ Ali, Wajahat (November 6, 2009). "Fort Hood has enough victims already". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Aunt: Fort Hood shooting suspect asked for discharge". The Washington Post. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "Muslim Veterans Group Says No Reports of Harassment of Islamic Soldiers". Fox News. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ James Hider and Philippe Naughton, "Fort Hood gunman Major Nidal Hasan had been trying to leave 'anti-Muslim' Army" Archived March 20, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Times Online, November 6, 2009.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (November 6, 2009). "Suspect Was to Be Sent to Afghanistan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Mcauliff, Michael; Kerry Burke; Helen Kennedy (November 6, 2009). "Fort Hood killer Nidal Malik Hasan opposed wars, so why did he snap?". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ "Sources Identify Major as Gunman in Deadly Shooting Rampage at Fort Hood". Fox News. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Jayson, Sharon; Reed, Dan; Johnson, Kevin (November 5, 2009). "Military: Fort Hood suspect is alive". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Fort Hood shooting: Texas army killer linked to September 11 terrorists Archived November 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Telegraph, November 7, 2009.

- ^ Alleged Shooter Tied to Mosque of 9 / 11 Hijackers, The New York Times, November 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c Drogin, Bob; Faye Fiore (November 7, 2007). "Retracing steps of suspected Fort Hood shooter, Nidal Malik Hasan". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ "Fort Hood Shooter Feared Impending War Deployment". Fox News. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Sherwell, Philip; Spillius, Alex (November 7, 2009). "Fort Hood shooting: Texas army killer linked to September 11 terrorists". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Shane, Scott; Dao, James (November 14, 2009). "Tangle of Clues About Suspect at Fort Hood". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ Ross, Brian; Schwartz, Rhonda (November 19, 2009). "Major Hasan's E-Mail: 'I Can't Wait to Join You' in Afterlife; American Official Says Accused Shooter Asked Radical Cleric When Is Jihad Appropriate?". ABC News. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ "Official: Nidal Hasan Had 'Unexplained Connections'". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 14, 2010. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ "FBI re-assessing past look at Fort Hood suspect". Associated Press. November 10, 2009. Archived from the original on November 14, 2009.

- ^ "Hasan's Ties Spark Government Blame Game". cbsnews.com. CBS News. November 11, 2009. Archived from the original on January 5, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ "Senior Official: More Hasan Ties to People Under Investigation by FBI". ABC News. November 10, 2009. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c Raghavan, Sudarsan (November 16, 2009). "Cleric says he was confidant to Hasan". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 1, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (December 27, 2008). "Muslim groups 'linked to September 11 hijackers spark fury over conference'; A Muslim group provoked outrage after inviting an extremist linked to the 9/11 hijackers to speak at a conference which is promoted with a picture of New York in flames". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ "Keynote Address at GEOINT Conference by Charles E. Allen, Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis /Chief Intelligence Officer". geointv.com. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on September 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c Egerton, Brooks (November 29, 2009). "Imam's e-mails to Fort Hood suspect Hasan tame compared to online rhetoric". The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ Kates, Brian (November 16, 2009). "Radical imam Anwar al-Aulaqi: Fort Hood gunman Nidal Hasan 'trusted' me, but I didn't spark rampage". The New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 19, 2009. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ^ Sacks, Ethan (November 11, 2009). "Who is Anwar al-Awlaki? Imam contacted by Fort Hood gunman Nidal Malik Hasan has long radical past". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 14, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ Barnes, Julian E. (January 15, 2010). "Gates makes recommendations in Ft. Hood shooting case". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Jakes, Lara (November 5, 2009). "AP sources: Authorities had concerns about suspect". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ "Esposito, Richard, Cole, Matthew, and Ross, Brian, "Officials: U.S. Army Told of Hasan's Contacts with al Qaeda; Army Major in Fort Hood Massacre Used 'Electronic Means' to Connect with Terrorists", ABC News, November 9, 2009, accessed November 10, 2009". ABCnews.go. Archived from the original on February 14, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ Martha Raddatz, Brian ross, Mary-Rose Abraham, Rehab El-Buri, Senior Official: More Hasan Ties to People Under Investigation by FBI Archived September 18, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, November 10, 2009.

- ^ ""Inside the Apartment of Nidal Hasan; Business Card", Time Magazine, accessed November 21, 2009". Time. November 11, 2009. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ "Hasan Called Himself 'Soldier of Allah' on Business Cards". Foxnews.com. November 12, 2009. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ "Ft. Hood gunman Maj. Nidal Hasan claimed radical Mohammadan title on business cards". Daily News. New York. November 12, 2009. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ Esposito, Richard; Mary-Rose Abraham; Rhonda Schwartz (November 12, 2009). "Major Hasan: Soldier of Allah; Many Ties to Jihad Web Sites". ABC News. Archived from the original on November 14, 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ Hsu, Spencer S. (November 8, 2009). "Links to imam followed in Fort Hood investigation". The Washington Post. Startribune.com. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ a b "E-Mails From Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan". The New York Times. August 20, 2013. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ Barnes, Julian (November 6, 2009). "Fort Hood victims bound for Dover Air Force Base". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Major Nidal Malik Hasan's Jihad warning signs ignored by political-correct military – Fort Hood Archived February 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine", CNN, November 6, 2009.

- ^ Newman, Maria (November 5, 2009). "12 Dead, 31 Wounded in Base Shootings". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 10, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "Neighbors: Alleged Fort Hood gunman emptied apartment". CNN. Fort Hood, Texas. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on November 7, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Who is Maj. Milik Hasan?". KXXV. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Pasha, Kamran (November 6, 2009). "A Muslim Soldier's View from Fort Hood". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ Gibbs, Nancy (November 11, 2009). "The Fort Hood Killer: Terrified ... or Terrorist?". Time. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Mattingly, David; Hernandez, Victor (November 9, 2009). "Fort Hood soldier: I 'started doing what I was trained to do'". CNN. Archived from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Christenson, Sig (October 14, 2010). "Chilling testimony at Fort Hood hearing". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on October 17, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Merrick, James L. (May 30, 2005). The Life And Religion Of Mohammed As Contained In The Sheeah Traditions Of The Hyat Ul Kuloob. Kessinger Publishing. p. 423. ISBN 978-1-4179-5536-7. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ Joseph Thomas (2013). The Universal Dictionary of Biography and Mythology: A-clu. Cosimo, Inc. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-61640-069-9. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ Mckinley Jr., James (November 12, 2009). "Second Officer Gives an Account of the Shooting at Ft. Hood". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Breed, Allen G.; Carlton, Jeff (November 6, 2009). "Soldiers say carnage could have been worse". Military Times. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ McCloskey, Megan, "Civilian police officer acted quickly to help subdue alleged gunman", Stars and Stripes, November 8, 2009.

- ^ Root, Jay (Associated Press), "Officer Gives Account of the Firefight At Fort Hood", Arizona Republic, November 8, 2009.

- ^ Ashley Powers, Robin Abcarian & Kate Linthicum (November 6, 2009). "Tales of terror and heroism emerge from Ft. Hood". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Carlton, Jeff (November 6, 2009). "Ft. Hood suspect reportedly shouted 'Allahu Akbar'". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 7, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Terrorism or Tragic Shooting? Analysts Divided on Fort Hood Massacre". Fox News. November 7, 2009. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

The authorities have not ruled out terrorism in the shooting, but they said the preliminary evidence suggests that it wasn't.

- ^ "Hospital: Fort Hood suspect moved to San Antonio". The Guardian. London. Associated Press. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Boudreaux, Richard (November 7, 2009). "Ft. Hood shooting suspect endured work pressure and ethnic taunts, his uncle says". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 23, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ "Hospital: Ft. Hood shooting suspect awake, talking". Archived from the original on November 13, 2009.

- ^ Todd, Brian; Ed Lavandera (November 13, 2009). "Alleged Fort Hood shooter paralyzed from waist down, lawyer says". CNN. Archived from the original on November 14, 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ Wall Street Journal_hpp_sections_news#articleTabs%3Darticle Fort Hood Suspect Recovering, The Wall Street Journal, published and retrieved December 16, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Jeremy Pelofsky, Adam Entous, Fort Hood suspect refuses to talk, iol.co.za, November 10, 2009.

- ^ Fort Hood Suspect Faces New Charges; The New York Times, December 2, 2009. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ Associated Press and Angela Brown, Fort Hood Suspect Charged with Murder Archived November 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine; cnn.com, December 2, 2009. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ a b Brown, Angela K.; Gearan, Anne (December 12, 2009). "Official: Prosecutor named in Fort Hood case". Army Times. Retrieved December 12, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Roupenian, Elisa (November 9, 2009). "Retired Colonel to Defend Accused Fort Hood Shooter: Accused Shooter Nidal Hasan Awake and Talking to Hospital Staff". ABC News. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ "Attorney: Hasan ordered confined until trial". Army Times. November 22, 2009.

- ^ Brown, Angela K. (November 23, 2009). "Atty: Hood suspect may use insanity defense". Army Times. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ "Army will delay mental evaluation of Hasan". Army Times. January 28, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ "Lawyer: Hasan barred from praying in Arabic". December 22, 2009. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ Bell County (TX) Jail. "Bell County – Daily Active Inmates". Archived from the original on March 1, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ Contreras, Guillermo (April 9, 2010). "Hasan moved to Bell County jail". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved April 9, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ a b c "Death penalty sought for Fort Hood shooting suspect". CNN. April 29, 2010. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ^ "Hassan's Attorney Seeks Closed Court Hearing". Tyler Morning Telegraph. Tyler, Texas. September 16, 2010. pp. 5B. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ Zucchino, David (October 13, 2010). "Hearing delayed in Ft. Hood shooting case". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 13, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ Zucchino, David (October 15, 2010). "More wounded soldiers recount horrors of Ft. Hood rampage". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ Zucchino, David (November 16, 2010). "Lawyers for Ft. Hood suspect decline to put on a defense". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Zucchino, David (November 18, 2010). "Army colonel recommends trial, death penalty in Fort Hood shooting". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 28, 2010. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Eli Lake (July 6, 2011). "Hasan eligible for death penalty at court-martial". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ^ "Judge sets 2012 trial date in Fort Hood shooting case". July 29, 2011. Archived from the original on July 29, 2011.

- ^ "Trial for accused Fort Hood shooter delayed". CNN. samachar.com. February 2, 2012. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ "Timeline for Judicial Process". Fort Hood Press Center. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ "Judge: Fort Hood suspect could be shaved". Army Times. Associated Press. July 25, 2012. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ Angela K. Brown (August 3, 2012). "Fort Hood shooting suspect fined by judge once more after again showing up in court with beard". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ Angela K. Brown (August 15, 2012). "Not guilty pleas expected in Fort Hood case". Army Times. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Angela K. Brown (August 16, 2012). "Fort Hood Suspect's Trial on Hold Over Beard". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 16, 2012. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Karen Brooks (August 27, 2012). McCune, Greg; Eastham, Todd (eds.). "Military says trial of accused Fort Hood shooter can go ahead". Chicago Tribune. Reuters. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ Manny Ramirez (September 6, 2012). "Fort Hood Shooting Suspect's Beard Must Be Shaved, Military Judge Rules". San Francs. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ a b Angela K. Brown (September 6, 2012). "Hasan ordered shaved; trial delayed". Austin Statesmen. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ "Lt. General says Hasan still has rank, getting paycheck – KXXV-TV News Channel 25 – Central Texas News and Weather for Waco, Temple, Killeen |". Kxxv.com. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ "Fort Hood accused Hasan 'can represent himself'". BBC. June 3, 2013. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ Forsyth, Jim (June 3, 2013). "Judge rules Fort Hood suspect can represent himself". NBCNews. Reuters. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, M. Alex (June 14, 2013). "Fort Hood gunman Nidal Hasan banned from arguing he was defending the Taliban". NBCNews. Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ Herridge, Catherine; Browne, Pamela (July 26, 2013). "Accused Fort Hood shooter releases statement to Fox News". Fox News. Archived from the original on October 14, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Allen, Nick (August 6, 2013). "I am the shooter: US army major Nidal Hasan declares as he faces court-martial over Fort Hood massacre". The Daily Telegraph. London. The Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on August 7, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Merchant, Nomaan; Weber, Paul (August 8, 2013). "Nidal Hasan Cross-Examination: Fort Hood Shooting Suspect Asks No Questions Of First Victim". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Attorneys allowed to leave trial of Fort Hood shooting suspect Nidal Hasan". The Guardian (UK). August 9, 2013. Archived from the original on August 9, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ DeLong, Katie (August 8, 2013). "Judge says Nidal Hasan defense team not allowed to opt out". Fox6 Now.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "Nidal Hasan's attorneys still trying to leave case". CNN. August 10, 2013. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ Jonsson, Patrik (August 14, 2013). "Seeking martyrdom, Nidal Hasan raises little fuss in Fort Hood courtroom". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on August 19, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ^ Merchant, Nomaan; Graczyk, Mike (August 14, 2013). "Massacre accused wants execution". The Nelson Mail. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Eric; Garza, Lisa (August 15, 2013). "Report on Fort Hood shooter blocked". Stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on October 6, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ^ "Jude Osborn rules out evidence of early extremism". UPI.com. August 19, 2013. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ Graczyk, Michael; Weber, Paul (August 20, 2013). "Nidal Hasan, Suspect in Fort Hood Shootings, will get his turn in court waits". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ Graczyk, Michael; Weber, Paul (August 21, 2013). "Defending Himself, Nidal Hasan Rests Fort Hood Case With No Witnesses". Time. Time Magazine. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ "No defense from suspect in 2009 Fort Hood shooting". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on August 21, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ "Hasan declines to give closing argument in Fort Hood shooting rampage trial". Fox News. August 22, 2013. Archived from the original on August 22, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny (August 28, 2013). "Jury Sentences Hasan to Death for Fort Hood Rampage". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ "Fort Hood shooting jury recommends death penalty for Nidal Hasan". CNN. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on August 30, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ Kenber, Billy (August 24, 2013). "Nidal Hasan convicted of Fort Hood killings". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ^ Penalty phase of Ft. Hood court-martial: prosecution rests. Fox News. 2013. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Fort Hood gunman Maj. Nidal Hasan sentenced to death". Fox News. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ Mears, Bill (August 27, 2013). "Fort Hood shooter Nidal Hasan addresses court-martial panel briefly". CNN. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Girdon, Jennifer (August 27, 2013). "Fort Hood shooter Nidal Hasan rests case without speaking at sentencing phase of trial". Fox News. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ "Fort Hood gunman Maj. Nidal Hasan sentenced to death". Fox News. August 28, 2013. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (August 28, 2013). "Fort Hood Gunman Nidal Hasan Sentenced To Death For 2009 Attack". NPR. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ "Sentenced to death, Forth Hood shooter has years of appeals to come". Archived from the original on November 5, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Esposito, Richard, Cole, Matthew, and Ross, Brian, "Officials: U.S. Army Told of Hasan's Contacts with al Qaeda; Army Major in Fort Hood Massacre Used 'Electronic Means' to Connect with Terrorists" Archived July 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, ABC News, November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009

- ^ "American Muslim Cleric Praises Fort Hood Shooter, ADL, November 11, 2009, accessed January 21, 2010". Adl.org. Archived from the original on November 29, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ "Anwar al-Awlaki: 'Nidal Hassan Did the Right Thing,'" The NEFA Foundation, November 9, 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2009. Archived March 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shane, Scott; "Born in U.S., a Radical Cleric Inspires Terror" Archived September 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, November 18, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ "NEFA transcript of Adam Gadahn: 'A Call to Arms'" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 15, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Fort Hood Shooting is Praised Online as Act of Heroism". Adl.org. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ "Peaceful preaching inside, violent message outside a New York mosque". CNN. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on November 7, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Allen, Nick (November 8, 2009). "Allen, Nick, "Fort Hood gunman had told US military colleagues that infidels should have their throats cut", The Telegraph, November 8, 2009, retrieved November 9, 2009". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ Whitelaw, Kevin (November 6, 2009). "Massacre Leaves 13 Dead At Fort Hood". NPR. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ Brachman, Jarret, and host Norris, Michelle, "All Things Considered: Expert Discusses Ties Between Hasan, Radical Imam" Archived May 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, NPR, November 10, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009

- ^ Eggerton, Brooks (November 17, 2009). "Fort Hood captain: Hasan wanted patients to face war crimes charges". The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on November 20, 2009. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ^ "Casey: I'm 'concerned' about backlash against Muslim soldiers". CNN. November 8, 2009. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ "'Meet the Press' transcript for Nov. 8, 2009, George Casey, Haley Barbour, Ed Rendell, David Brooks, E.J. Dionne, Rachel Maddow, Ed Gillespie, Tom Brokaw". NBC News. February 12, 2010. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ "Ex-F.B.I. Director to Examine Ft. Hood"; The New York Times, published and retrieved on December 8, 2009.

- ^ "Final Report of the William H. Webster Commission on The Federal Bureau of Investigation, Counterterrorist Intelligence, and the Events at Fort Hood, Texas, on November 5, 2009". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012.

- ^ "CQ Transcript: Reps. Van Hollen, Pence, Sen. Lieberman Gov.-elect McDonnell on 'Fox News Sunday'". November 8, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Johnson, Bridget (November 9, 2009). "Lieberman wants probe into 'terrorist attack' by major on Fort Hood". The Hill. Archived from the original on November 12, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ "Table of Contents: November 23, 2009". Time Magazine. November 23, 2009. Archived from the original on November 17, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ a b c "The Fort Hood Killer: Terrified ... or Terrorist?". Nancy Gibbs. Time magazine. November 11, 2009.

- ^ Patrik Jonsson and Tracey D. Samuelson, "Fort Hood suspect: Portrait of a terrorist?" Archived November 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Christian Science Monitor, November 9, 2009.

- ^ Scott, Shane & Dao, James (November 14, 2009). "Investigators Study Tangle of Clues on Fort Hood Suspect". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ "Nidal Hasan's beard shaved off by force". The Guardian. September 4, 2013. Archived from the original on September 5, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ^ Shaughnessy, Larry (September 5, 2013). "Nidal Hasan's beard shaved off at Fort Leavenworth Prison". CNN. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ^ Zaimov, Stoyan (September 5, 2013). "Military forcefully shaves Nidal Hasan's beard; Lawyer to sue". The Christian Post. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ^ Carter, Chelsea (August 29, 2014). "Fort Hood shooter writes to ISIS leader, asks to become 'citizen' of Islamic State". CNN. Archived from the original on August 29, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ Herridge, Catherine (August 28, 2014). "Fort Hood shooter says he wants to become 'citizen' of Islamic State caliphate". Fox News. Archived from the original on August 29, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ "בכורה: אריק ברמן - "רס"ן נידאל חסן" - וואלה! תרבות". March 22, 2011.

- ^ "אריק ברמן - רב סרן נידל חסן (לא סיפור פשוט)". YouTube. May 24, 2011.

- ^ "Eric Berman - אריק ברמן – Rav Seren Nidal Hassan (Lo Sipur Pashut) - (רב סרן נידל חסן (לא סיפור פשוט".

- 1970 births

- 21st-century American criminals

- American mass murderers

- Muslims from Virginia

- American people convicted of murder

- American people of Palestinian descent

- American psychiatrists

- American prisoners sentenced to death

- Anwar al-Awlaki

- Criminals from Virginia

- Islamist mass murderers

- Living people

- Military in Texas

- Military personnel from Virginia

- Military psychiatrists

- People convicted of murder by the United States military

- People from Arlington County, Virginia

- People with paraplegia

- Prisoners sentenced to death by the United States military

- Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences alumni

- United States Army Medical Corps officers

- United States Army personnel who were court-martialed

- Virginia Tech alumni

- Inmates of United States Disciplinary Barracks

- Opposition to the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021)