Ependymoma

| Ependymoma | |

|---|---|

| |

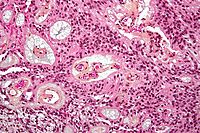

| Micrograph of an ependymoma. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Neuro-oncology |

| Prognosis | Five-year survival rate: 83.9%[1] |

| Frequency | 200 new cases each year in the United States[2] |

An ependymoma is a tumor that arises from the ependyma, a tissue of the central nervous system. Usually, in pediatric cases the location is intracranial, while in adults it is spinal. The common location of intracranial ependymomas is the floor of the fourth ventricle. Rarely, ependymomas can occur in the pelvic cavity.

Syringomyelia can be caused by an ependymoma. Ependymomas are also seen with neurofibromatosis type II.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Source:[3]

- severe headache

- visual loss (due to papilledema)

- vomiting

- bilateral Babinski sign

- drowsiness (after several hours of the above symptoms)

- gait change (rotation of feet when walking)

- impaction/constipation

- back flexibility

Morphology

[edit]Ependymomas are composed of cells with regular, round to oval nuclei. There is a variably dense fibrillary background. Tumor cells may form gland-like round or elongated structures that resemble the embryologic ependymal canal, with long, delicate processes extending into the lumen; more frequently present are perivascular pseudorosettes in which tumor cells are arranged around vessels with an intervening zone consisting of thin ependymal processes directed toward the wall of the vessel.[4]

It has been suggested that ependymomas are derived from radial glia, despite their name suggesting an ependymal origin.[5]

-

Micrograph of a myxopapillary ependymoma. HPS stain.

-

Ependymoma of 4.ventricle in MRI.

-

Ependymoma of 4.ventricle in MRI.

-

Ependymoma of 4.ventricle in MRI. Left without, right with contrast-enhancement.

Ependymoma tumors

[edit]Ependymomas make up about 5% of adult intracranial gliomas and up to 10% of childhood tumors of the central nervous system (CNS). Their occurrence seems to peak at age 5 years and then again at age 35. They develop from cells that line both the hollow cavities of the brain and the canal containing the spinal cord, but they usually arise from the floor of the fourth ventricle, situated in the lower back portion of the brain, where they may produce headache, nausea and vomiting by obstructing the flow of cerebrospinal fluid. This obstruction may also cause hydrocephalus. They may also arise in the spinal cord, conus medullaris and supratentorial locations.[6] Other symptoms can include (but are not limited to): loss of appetite, difficulty sleeping, temporary inability to distinguish colors, uncontrollable twitching, seeing vertical or horizontal lines when in bright light, and temporary memory loss. It should be remembered that these symptoms also are prevalent in many other illnesses not associated with ependymoma.[citation needed]

About 10% of ependymomas are benign myxopapillary ependymoma (MPE).[7] MPE is a localized and slow-growing low-grade tumor, which originates almost exclusively from the lumbosacral nervous tissue of young patients.[7] On the other hand, it is the most common tumor of the lumbosacral canal comprising about 90% of all tumoral lesions in this region.[8]

Although some ependymomas are of a more anaplastic and malignant type, most of them are not anaplastic. Well-differentiated ependymomas are usually treated with surgery. For other ependymomas, total surgical removal is the preferred treatment in addition to radiation therapy. The malignant (anaplastic) varieties of this tumor, malignant ependymoma and the ependymoblastoma, are treated similarly to medulloblastoma but the prognosis is much less favorable. Malignant ependymomas may be treated with a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Ependymoblastomas, which occur in infants and children younger than 5 years of age, may spread through the cerebrospinal fluid and usually require radiation therapy. The subependymoma, a variant of the ependymoma, is apt to arise in the fourth ventricle but may occur in the septum pellucidum and the cervical spinal cord. It usually affects people over 40 years of age and more often affects men than women.[9]

Extraspinal ependymoma (EEP), also known as extradural ependymoma, may be an unusual form of teratoma[10] or may be confused with a sacrococcygeal teratoma.[11]

Treatment

[edit]Guidelines for initial management for ependymoma are maximum surgical resection followed by radiation.[12] Chemotherapy is of limited use and reserved for special cases including young children and those with tumor present after resection. Prophylactic craniospinal irradiation is of variable use and is a source of controversy given that most recurrence occurs at the site of resection and therefore is of debatable efficacy.[13][12] Confirmation of cerebrospinal infiltration warrants more expansive radiation fields.[14]

Prognosis of recurrence is poor and often indicates palliative care to manage symptoms.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ "Ependymoma Diagnosis and Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ "Ependymoma". St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ PRITE 2010 Part II q.13

- ^ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). "Ch. 28 The central nervous system". Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (7th ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.[page needed]

- ^ Poppleton H, Gilbertson RJ (January 2007). "Stem cells of ependymoma". British Journal of Cancer. 96 (1): 6–10. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603519. PMC 2360214. PMID 17179988.

- ^ Goel A, Gaillard F. "Ependymoma". Radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ a b Mehrjardi MZ, Mirzaei S, Haghighatkhah HR (2017). "The many faces of primary cauda equina myxopapillary ependymoma: Clinicoradiological manifestations of two cases and review of the literature". Romanian Neurosurgery. 31 (3): 385–90. doi:10.1515/romneu-2017-0062.

- ^ Duong LM, McCarthy BJ, McLendon RE, Dolecek TA, Kruchko C, Douglas LL, Ajani UA (September 2012). "Descriptive epidemiology of malignant and nonmalignant primary spinal cord, spinal meninges, and cauda equina tumors, United States, 2004-2007". Cancer. 118 (17): 4220–4227. doi:10.1002/cncr.27390. PMC 4484585. PMID 22907705.

- ^ Pan E, Prados MD (2003). "Ependymoma". Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (6th ed.). BC Decker.

- ^ Aktuğ T, Hakgüder G, Sarioğlu S, Akgür FM, Olguner M, Pabuçcuoğlu U (March 2000). "Sacrococcygeal extraspinal ependymomas: the role of coccygectomy". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 35 (3): 515–518. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(00)90228-8. PMID 10726703.

- ^ Hany MA, Bouvier R, Ranchère D, Bergeron C, Schell M, Chappuis JP, et al. (2009). "Case report: a preterm infant with an extradural myxopapillary ependymoma component of a teratoma and high levels of alpha-fetoprotein". Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 15 (5): 437–441. doi:10.3109/08880019809016573. PMID 9783311.

- ^ a b Reni M (2003). "Guidelines for the treatment of adult intra-cranial grade II-III ependymal tumours". Forum. 13 (1): 90–98. PMID 14732890.

- ^ Merchant TE, Fouladi M (December 2005). "Ependymoma: new therapeutic approaches including radiation and chemotherapy". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 75 (3): 287–299. doi:10.1007/s11060-005-6753-9. PMID 16195801. S2CID 37438304.

- ^ "Ependymoma". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Merchant TE, Boop FA, Kun LE, Sanford RA (May 2008). "A retrospective study of surgery and reirradiation for recurrent ependymoma". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 71 (1): 87–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.09.037. PMID 18406885.