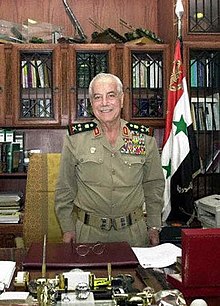

Mustafa Tlass

Mustafa Tlass | |

|---|---|

مصطفى طلاس | |

| |

| 12th Minister of Defense | |

| In office 22 March 1972 – 12 May 2004 | |

| President | Nureddin al-Atassi (1968–1970) Ahmad al-Khatib (1970–1971) Hafez al-Assad (1971–2000) Bashar al-Assad (2000–2004) |

| Preceded by | Hafez Assad |

| Succeeded by | Hasan Turkmani |

| Chief of Staff of the Syrian Army | |

| In office 1968–1972 | |

| Preceded by | Ahmed Suidani |

| Succeeded by | Yusuf Shakkur |

| Member of the Regional Command of the Syrian Regional Branch | |

| In office 28 September 1968 – 9 June 2005 | |

| In office 4 April 1965 – December 1965 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mustafa Abdul Qadir Tlass 11 May 1932 Rastan, French Syria |

| Died | 27 June 2017 (aged 85) Bobigny, France |

| Political party | Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party – Syria Region of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party Was a member of the original Ba'ath Party and its Syrian Regional Branch until 1966 |

| Relations | Nahed Tlass (daughter) Manaf Tlass (son) Firas Tlass (son) Abdul Razzaq Tlass (nephew) Akram Ojjeh (Son-in-law) Mansour Ojjeh (Grandson-in-law) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Syrian Army |

| Years of service | 1952–2004 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | |

Mustafa Abdul Qadir Tlass (Arabic: مصطفى عبد القادر طلاس, romanized: Musṭafā ʿAbd al-Qādir Ṭalās; 11 May 1932 – 27 June 2017) was a Syrian senior military officer and politician who was Syria's minister of defense from 1972 to 2004.[1] He was part of the four-member Regional Command during the Hafez Assad era.

Early life and education

[edit]Tlass was born in Rastan near the city of Homs to a prominent local Sunni Muslim family on 11 May 1932.[2][3] His father, Abdul Qadir Tlass, was a minor Sunni noble who made a living during the Ottoman period by selling ammunition to the Turkish garrisons.[4] On the other hand, members of his family also worked for the French occupiers after the First World War.[5] His paternal grandmother was of Circassian origin and his mother was of Turkish descent.[6] Tlass is said to also have some Alawite family connections through his mother.[2][7] He received primary and secondary education in Homs.[2] In 1952, he entered the Homs Military Academy.[2]

Career

[edit]

Tlass joined the Ba'ath Party at the age of 15, and met Hafez al-Assad when studying at the military academy in Homs.[8] The two officers became friends when they were both stationed in Cairo during the period of 1958–1961 United Arab Republic merger between Syria and Egypt: while ardent Pan Arab nationalists, they both worked to break up the union, which they viewed as unfairly balanced in Egypt's favor.[citation needed] When Hafez al-Assad was briefly imprisoned by Nasser at the breakup of the union, Tlass fled and rescued his wife and sons to Syria.[4]

During the 1960s, Hafez al-Assad rose to prominence in the Syrian government through the 1963 coup d'état, backed by the Ba'ath party. He then promoted Tlass to high-ranking military and party positions. In 1965, while he was Ba'athist army commander of Homs, Lieutenant Colonel Mustafa Tlass arrested his pro-government comrades.[9] A 1966 coup by an Alawite-dominated Ba'ath faction further strengthened al-Assad, and by association Tlass.[citation needed] Tensions within the government soon became apparent, however, with al-Assad emerging as the prime proponent of a pragmatist, military-based faction opposed to the ideological radicalism of the dominant ultra-leftists. Syrian defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War embarrassed the government, and in 1968 al-Assad managed to install Tlass as new Chief-of-Staff.[citation needed] After the debacle of an attempted Syrian intervention in the Black September conflict, the power struggle came to open conflict.[citation needed]

In 1969, Tlass led a military mission to Beijing, and secured weapons deals with the Chinese government.[10][11][12] In a move deliberately calculated to antagonize the Soviet Union to stay out of the succession dispute then going on in Syria, Mustafa Tlass allowed himself to be photographed waving Mao Zedong's Little Red Book, just two months after bloody clashes between Chinese and Soviet armies on the Ussuri river.[13][14] The Soviet Union then agreed to back down and sell Syria weapons.[citation needed]

Under cover of the 1970 "Corrective Revolution", Hafez al-Assad seized power and installed himself as Dictator. Tlass was promoted to minister of defense in 1972, and became one of al-Assad's most trusted loyalists during the following 30 years of one-man rule in Syria. As'ad AbuKhalil argues that Mustafa Tlass was well-suited for Hafez al-Assad as a defense minister in that "he had no power base, he was mediocre, and he had no political skills, and his loyalty to his boss was complete."[15] During his term as defense minister, Mustafa Tlass was functional in suppressing all dissent regardless of being Islamists or democrats.[16]

On 19 October 1999, defence minister of China, General Chi Haotian, after meeting with Mustafa Tlass in Damascus to discuss expanding military ties between Syria and China, flew directly to Israel and met with Ehud Barak, the then prime minister and defence minister of Israel where they discussed military relations. Among the military arrangements was a 1 billion dollar Israeli Russian sale of military aircraft to China, which were to be jointly produced by Russia and Israel.[17]

At the beginning of the 2000s, Tlass was also deputy prime minister in addition to his post as defense minister.[18] He was also a member of Baath Party's central committee.[19] His other party roles included the head of the party military bureau and chairman of the party military committee.[20]

Controversial writings and controversies

[edit]Tlass attempted to create a reputation for himself as a man of culture and emerged as an important patron of Syrian literature. He published several books of his own, and started a publishing house, Tlass Books, which has been internationally criticized[21] for publishing alleged anti-Semitic materials.[4]

In 1998, Syrian Defense Minister Tlass boasted to Al Bayan newspaper that he was the one who gave the green light to "the resistance" in Lebanon to attack and kill 241 US marines and 58 French paratroopers, but that he prevented attacks on the Italian soldiers of the multi-national force because "I do not want a single tear falling from the eyes of [Italian actress] Gina Lollobrigida, whom [I] loved ever since my youth."[22][23] In October of the same year, Tlass stated that there was no such country as Jordan, but only "South Syria".[24]

Tlass had also boasted to the National Assembly about cannibalist atrocities committed against Israeli soldiers who fell captive in the Yom Kippur war. "I gave the Medal of the Republic's Hero, to a soldier from Aleppo, who killed 28 Jewish soldiers. He did not use the military weapon to kill them but utilized the ax to decapitate them. He then devoured the neck of one of them and ate it in front of the people. I am proud of his courage and bravery, for he actually killed by himself 28 Jews by count and cash."[25][26]

There have been three missing Israeli soldiers in the Bekaa valley since the June 1982 war in Lebanon. Tlass allegedly told a Saudi magazine: "We sent Israel the bones of dogs, and Israel may protest as much as it likes."[27]

During his career, Tlass also became known for colorful language. In 1991, when Syria was participating on the Coalition side in the Gulf War, he stated that he felt "an overwhelming joy" when Saddam Hussein sent SCUD-missiles towards Israel. In August 1998, Tlass caused a minor uproar in Arab political circles, when he denounced Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat as "the son of sixty thousand whores."[28][29] The long-standing conflict between the Assad government and the Palestine Liberation Organization would not end until after Hafez al-Assad's death in 2000.[citation needed]

In 2000, the widow and children of Ira Weinstein who was killed in a February 1996 Hamas suicide bombing, filed a lawsuit against Tlass and the head of Syrian military intelligence in Lebanon, Ghazi Kanaan, charging that they were responsible for providing the perpetrators with material resources and training.[30]

In an interview which aired RT on 8 June 2009 (as translated by MEMRI), Tlass claimed that actress Gina Lollobrigida had once told him that he was the "one love in my life." He also claimed that Lady Diana wrote him letters that "were full of love and appreciation", and that Prince Charles gave him a gold-plated Sterling submachine gun as a gift.[31]

Books

[edit]In 1986, he defended his doctoral dissertation on the military strategy of Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgy Zhukov at the Sorbonne. However, on the same year, his doctoral dissertation defense was rejected after the media publicised several anti-Semitic statements made by him.[32]

Tlass also wrote books about Syria's military and political history and also books of poetry, general Arab history, and a history of the military tactics used by Muhammad.[33] His writings allegedly reflect anti-Semitism and belief in conspiracy theories.[33] He also published two-volume memoirs (eventually extended to five), namely Mirat Hayati (Reflections of my life) in 2005.[33] The memoirs were widely ridiculed around the Arab world and outraged Bashar Al-Assad due to its content, making various claims about ordering summary executions of dissidents and Israelis and crediting himself for bringing Hafez and Bashar to power.[34] Tlass, whom close friends had described as a sex-obsessed maniac who tried to sleep with as many women as he could, also described in graphic detail his outlandish attempts at seducing women: "As my eyes were fixated on her beautiful breasts I noticed she was wearing a white and transparent nightgown that concealed nothing of God's creation," Tlass wrote about a neighbor he fantasized for days.[35]

The Matzah of Zion

[edit]In 1983, Tlass wrote and published The Matzah of Zion, which is a treatment of the Damascus affair of 1840 that repeats the ancient "blood libel", that Jews use the blood of murdered non-Jews in religious rituals such as baking Matza bread.[36] In this book, he argues that the true religious beliefs of Jews are "black hatred against all humans and religions," and that no Arab country should ever sign a peace treaty with Israel.[37] Tlass re-printed the book several times, and stood by its conclusions. Following the book's publication, Tlass told Der Spiegel, that this accusation against Jews was valid and that his book is "an historical study ... based on documents from France, Vienna and the American University in Beirut."[37][38]

Regarding the book, Tlass stated that "I intend through publication of this book to throw light on some secrets of the Jewish religion based on the conduct of the Jews and their fanaticism" and that both Eastern and Western civilizations threw Jews into ghettos only after recognizing their "destructive badness". He also claimed that since 1840, "every mother warned her child: Do not stray far from home. The Jew may come by and put you in his sack to kill you and suck your blood for the Matzah of Zion."[39]

In 1991 The Matzah of Zion was translated into English. Egyptian producer Munir Radhi subsequently decided it was the ideal "Arab answer" to the film Schindler's List and later announced plans to produce a film adaptation of The Matzah of Zion.[40] The book also reportedly served as a "scientific" basis for a renewal of the blood libel charge in international forums. In 2001, Al-Ahram published an article titled "A Jewish Matzah Made from Arab Blood" which summarized The Matzah of Zion, concluding that: "The bestial drive to knead Passover matzahs with the blood of non-Jews is [confirmed] in the records of the Palestinian police where there are many recorded cases of the bodies of Arab children who had disappeared being found, torn to pieces without a single drop of blood. The most reasonable explanation is that the blood was taken to be kneaded into the dough of extremist Jews to be used in matzahs to be devoured during Passover."[38]

After Hafez al-Assad

[edit]The succession of Bashar al-Assad, Hafez's son, seems to have been secured by a group of senior officials, including Tlass.[41] After the death of Assad in 2000, a 9-member committee was formed to oversee the transition period, and Tlass was among its members.[42]

Whether true or not, Tlass and his supporters were viewed by many as opponents of the discreet liberalization pursued by the younger al-Assad, and to maintain Syria's hardline foreign policy stances; but also as fighting for established privileges, having been heavily involved in government corruption. In February 2002 in the Jordanian daily Al Dustour stated that Tlass submitted his letter of resignation to Bashar al-Assad, and was set to step down in July 2002.[30] However, in 2004, Tlass was replaced by Hasan Turkmani as defense minister.[20][43] It is also argued that Shawkat pushed for the removal of Mustafa Tlass.[44] Tlass also quit the regional command in 2005.[45]

Mustafa Tlass and his son, Firas, both left Syria after the revolt against Assad began in 2011.[46] Mustafa Tlass left for France for what he described as medical treatment.[46] Firas, a business tycoon, left Syria for Egypt in 2011, too.[46] It is also reported that he is in Dubai.[47]

In July 2012, Manaf Tlass, a Syrian officer and another son of Mustafa, defected from the Assad government and fled to Turkey and then to France.[46]

Personal life and death

[edit]Tlass married Lamia Al Jabiri, a member of the Aleppine aristocracy,[8] in 1958.[2] His marriage secured his position among the traditional elite and enabled him to advance socially.[4] They had four children: Nahid (born 1958), Firas (born 1960), Manaf (born 1964), and Sarya (born 1978).[48] His daughter Nahid was married to Saudi millionaire arms dealer Akram Ojjeh, forty years her senior.[49] She has lived in Paris since the onset of Syrian uprising.[49] His younger daughter, Sarya, is married to a Lebanese from Baalbak.[4]

Tlass was the only member of the Ba'ath government who took part in the traditional social establishment of Syria.[4] His hobbies are said to include horseback riding, tennis, and swimming.[2]

Tlass died on 27 June 2017 in Avicenne Hospital in Paris, France, at the age of 85.[50]

Honours

[edit]National honours

[edit]- Syria:

Order of the Umayyads (1st class)

Order of the Umayyads (1st class) Order of Civil Merit (1st class)

Order of Civil Merit (1st class) Order of Military Honor (1st class)

Order of Military Honor (1st class) Order for Bravery (1st class)

Order for Bravery (1st class) Order of Devotion (Special class)

Order of Devotion (Special class) Medal for Long and Impeccable Service (Special class)

Medal for Long and Impeccable Service (Special class) Medal for Preparation

Medal for PreparationOrder of Federation

Commemorative Medal 'March 8'

Commemorative Medal 'March 8' Commemorative Medal 'October 6'

Commemorative Medal 'October 6'

Foreign honours

[edit]- Austria:

- Egypt:

- East Germany:

- Greece:

- Kazakhstan:

Order of Friendship (1st class)

Order of Friendship (1st class)

- Lebanon:

- North Korea:

Order of the National Flag (1st class)

Order of the National Flag (1st class) Order of the National Flag (3rd class)

Order of the National Flag (3rd class)

- Pakistan:

Nishan-e-Imtiaz (1st class)

Nishan-e-Imtiaz (1st class)

- Russia:

- Soviet Union:

Bibliography

[edit]- Dagher, Sam (2019). Assad or We Burn the Country (First U.S. ed.). New York: Little, Brown & Company. ISBN 978-0316556705.

References

[edit]- ^ "Profile: Mustafa Tlas". BBC. 2004. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Man who Enraged the Palestinians: Syrian Defense Minister Mustafa Tlas". The Estimate. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ Who's Who in the Arab World 2007-2008. Beirut: Publitec. 2011. p. 809. ISBN 978-3-11-093004-7.

- ^ a b c d e f "Lt. Gen. Mustafa Tlass". Middle East Intelligence Bulletin. 2 (6). 1 July 2000.

- ^ Joseph Kechichian (27 July 2012). "Syria is bigger than individuals, says defected brigadier". Gulf News. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Hanna Batatu (1999), Syria's Peasantry, the Descendants of Its Lesser Rural Notables, and Their Politics, Princeton University Press, p. 218 (Table 18-1), ISBN 140084584X

- ^ Shmuel Bar (2006). "Bashar's Syria: The Regime and its Strategic Worldview" (PDF). Comparative Strategy. 25 (5): 353–445. doi:10.1080/01495930601105412. S2CID 154739379.

- ^ a b Briscoe, Ivan; Floor Janssen Rosan Smits (November 2012). "Stability and economic recovery after Assad: key steps for Syria's post-conflict transition" (PDF). Clingendael: 1–51. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Fisk, Robert (6 March 2012). "With that history, why did we think Syria would fall?". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ Peter Mansfield (1973). The Middle East: a political and economic survey. Oxford University Press. p. 480. ISBN 0-19-215933-X. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ George Meri Haddad, Jūrj Marʻī Ḥaddād (1973). Revolutions and Military Rule in the Middle East: The Arab states pt. I: Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Jordan, Volume 2. R. Speller. p. 380. ISBN 9780831500603. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Europa Publications Limited (1997). The Middle East and North Africa, Volume 43. Europa Publications. p. 905. ISBN 1-85743-030-1. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Robert Owen Freedman (1982). The Soviet Policy Toward the Middle East Since 1970. Praeger. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-03-061362-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Robert Owen Freedman (1991). Moscow and the Middle East: Soviet policy since the invasion of Afghanistan. CUP Archive. p. 40. ISBN 0-521-35976-7. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ AbuKhalil, As'ad (20 July 2012). "Damascus Bombs and Mysteries". Al Akhbar. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ Koelbl, Susanne (21 February 2005). "A 101 Course in Mideast Dictatorships". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ "China defense minister visits Israel". Archived 30 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine World Tribune. 21 October 1999

- ^ Bruce Maddy-Weitzman (2002). Middle East Contemporary Survey, Vol. 24, 2000. The Moshe Dayan Center. p. 557. ISBN 978-965-224-054-5. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Moubayed, Sami (26 May – 1 June 2005). "The faint smell of jasmine". Al Ahram Weekly. 744. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ a b Hinnebusch, Raymond (2011). "The Ba'th Party in Post-Ba'thist Syria: President, Party and the Struggle for 'Reform'". Middle East Critique. 20 (2): 109–125. doi:10.1080/19436149.2011.572408. S2CID 144573563.

- ^ Question of Violation of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms in Any Part of the World. Archived 6 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Written statement submitted by the Association for World Education, 10 February 2004

- ^ "A crush on Lollobrigida benefited Italian troops". Deseret News. 3 January 1998. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Karmon, Ely (28 February 2010). "No models of example". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Schenker, David (2003). Dancing with Saddam (PDF). Lanham: Lexington Books. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Official Gazette of Syria (11 July 1974 Issue)

- ^ Letter Maurice Swan The New York Times 23 June 1975

- ^ London based Saudi weekly, 4–10 August 1984.

- ^ "Arafat 'son of 60,000 whores'". BBC. 4 August 1999. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Gambill, Gary C. (April 2001). "Syria's Foreign Relations: The Palestinian Authority". Middle East Intelligence Bulletin. 3 (4). Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ a b Gambill, Gary C. (October 2002). "Sponsoring Terrorism: Syria and Hamas". Middle East Intelligence Bulletin. 4 (10). Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Former Syrian Minister of Defense Mustafa Tlass Displays Personal Memorabilia and Reminisces about His Imaginary Affairs with Actress Gina Lollobrigida and Lady Di, MEMRI, Transcript – Clip No. 2144, 8 June 2009.

- ^ "French Government Has Reportedly Facilitated Review of Doctoral Dissertation by Anti-semitic Author". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 22 June 1986. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Aboul Enein, Youssef H. (May–June 2005). "Syrian Defense Minister General Mustafa Tlas: Memoirs, Volume 2" (PDF). Military Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ Dagher 2019, p. 246.

- ^ Dagher 2019, p. 96.

- ^ An Anti-Jewish Book Linked to Syrian Aide, New York Times, 15 July 1986.

- ^ a b "Literature Based on Mixed Sources – Classic Blood Libel: Mustafa Tlas' Matzah of Zion". ADL. Archived from the original on 13 April 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ a b Blood Libel Judith Apter Klinghoffer, History News Network, 19 December 2006.

- ^ Arabs' Hatred of Jews: Can the Carnage Be a Surprise? Abraham Cooper, Los Angeles Times, 12 September 1986.

- ^ Jeffrey Goldberg (2008). Prisoners: A Story of Friendship and Terror. Vintage Books. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-375-72670-5.

- ^ Ghadbian, Najib (Autumn 2001). "The New Asad: Dynamics of Continuity and Change in Syria" (PDF). Middle East Journal. 55 (4): 624–641. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ "Bashar Aims to Consolidate Power in the Short-Term and to Open up Gradually". APS Diplomat News Service. 19 June 2000. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Flynt Lawrence Leverett (1 January 2005). Inheriting Syria: Bashar's Trial by Fire. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 190. ISBN 978-0-8157-5206-6. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Gambill, Gary C. (February 2002). "The Military-Intelligence Shakeup in Syria". Middle East Intelligence Bulletin. 4 (2). Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "Syria military. Minister of Defense". Global Security. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d Oweis, Khaled Yacoub (5 July 2012). "Syrian general breaks from Assad's inner circle". Reuters. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ Julian Borger; Martin Chulov (5 July 2012). "Top Syrian general 'defects to Turkey'". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ "Personal Profile". Firas Tlass website. Archived from the original on 28 May 2004. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Defection of Syrian general 'significant': US". AFP. 6 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ "وفاة وزير الدفاع السوري الأسبق مصطفى طلاس".

- 1932 births

- 2017 deaths

- Syrian people of Circassian descent

- Antisemitism in Syria

- Blood libel

- Deputy prime ministers of Syria

- Chiefs of staff of the Syrian Army

- Homs Military Academy alumni

- Members of the Regional Command of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party – Syria Region

- People from Homs Governorate

- Syrian Arab nationalists

- Syrian conspiracy theorists

- Ministers of defense of Syria

- Syrian nationalists

- Syrian anti-communists

- Syrian people of Turkish descent

- Syrian Sunni Muslims

- Tlass family

- Recipients of the Order of Friendship of Peoples

- Recipients of the Scharnhorst Order

- Recipients of the Grand Star of the Decoration for Services to the Republic of Austria

- Recipients of Nishan-e-Imtiaz

- Recipients of the Order of Zhukov

- Grand Cordons of the National Order of the Cedar

- Recipients of the Order of Merit (Egypt)

- People of the Lebanese Civil War