FIFA Club World Cup

| |

| Organising body | FIFA |

|---|---|

| Founded | 2000 |

| Region | International |

| Number of teams | 32 (from 6 confederations) |

| Related competitions | FIFA Intercontinental Cup |

| Current champions | (1st title) |

| Most successful club(s) | (5 titles) |

| Website | fifa.com/clubworldcup |

The FIFA Club World Cup is an international men's association football competition organised by the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), the sport's global governing body. The competition was first contested in 2000 as the FIFA Club World Championship. It was not held from 2001 to 2004 due to a combination of factors in the cancelled 2001 tournament, most importantly the collapse of FIFA's marketing partner International Sport and Leisure (ISL), but in 2005 it changed to an annual competition through 2023. Following the 2023 edition, the tournament was revamped to a quadrennial competition starting in 2025. Views differ as to the cup's prestige: it struggles to attract interest in most of Europe, and is the object of heated debate in South America.[1][2]

The first FIFA Club World Championship took place in Brazil in 2000, during which year it ran in parallel with the Intercontinental Cup, a competition played by the winners of the UEFA Champions League and the Copa Libertadores, with the champions of each tournament both recognised (in 2017) by FIFA as club world champions.[3] In 2005, the Intercontinental Cup was merged with the FIFA Club World Championship, and in 2006, the tournament was renamed as the FIFA Club World Cup. The winner of the Club World Cup receives the FIFA Club World Cup trophy and a FIFA World Champions certificate.

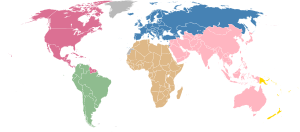

The new format, which will come into effect with the 2025 edition, features 32 teams competing for the title at venues within the host nation; 12 teams from Europe, 6 from South America, 4 from Asia, 4 from Africa, 4 from North, Central America and Caribbean, 1 from Oceania, and 1 team from the host nation. The teams are drawn into eight groups of four, with each team playing three group stage matches in a round-robin format. The top two teams from each group advance to the knockout stage, starting with the round of 16 and culminating with the final.

Real Madrid hold the record for most titles, having won the competition on five occasions. Corinthians' inaugural victory remains the best result from a host nation's national league champions. Teams from Spain have won the tournament eight times, the most for any nation. England has the largest number of winning teams, with four clubs having won the tournament. The current world champions are Manchester City, who defeated Fluminense 4–0 in the 2023 final.

History

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (November 2023) |

Origin

The first club tournament to be billed as the Football World Championship was held in 1887, in which FA Cup winners Aston Villa beat Scottish Cup winners Hibernian, the winners of the only national competitions at the time. The first time when the champions of two European leagues met was in what was nicknamed the 1895 World Championship, when English champions Sunderland beat Scottish champions Heart of Midlothian 5–3.[4] Ironically, the Sunderland lineup in the 1895 World Championship consisted entirely of Scottish players – Scottish players who moved to England to play professionally in those days were known as the Scotch Professors.[4][5]

The first attempt at creating a global club football tournament, according to FIFA, was in 1909, 21 years before the first FIFA World Cup.[6] The Sir Thomas Lipton Trophy was held in Italy in 1909 and 1911, and contested by English, Italian, German and Swiss clubs.[7] English amateur team West Auckland won on both occasions.[8]

The idea that FIFA should organise international club competitions dates from the beginning of the 1950s.[9] In 1951, the Brazilian FA created Copa Rio, also called "World Champions Cup" in Brazil, with a view to being a Club World Cup (a "club version" of the FIFA World Cup). FIFA president Jules Rimet was asked about FIFA's involvement in Copa Rio, and stated that it was not under FIFA's jurisdiction since it was organised and sponsored by the Brazilian FA.[10] FIFA board officials Stanley Rous and Ottorino Barassi participated personally, albeit not as FIFA assignees, in the organisation of Copa Rio in 1951. Rous' role was the negotiations with European clubs, whereas Barassi did the same and also helped form the framework of the competition. The Italian press regarded the competition as an "impressive project" that "was greeted so enthusiastically by FIFA officials Stanley Rous and Jules Rimet to the extent of almost giving it an official FIFA stamp."[11] Because of the difficulty the Brazilian FA found in bringing European clubs to the competition, the O Estado de S. Paulo newspaper suggested that there should be FIFA involvement in the programming of international club competitions saying that, "ideally, international tournaments, here or abroad, should be played with a schedule set by FIFA".[12] Palmeiras beat Juventus at Maracanã with over 200,000 spectators in attendance at the final of the 1951 Copa Rio, and were hailed as the first ever Club World Champions by the whole Brazilian press.[13][14] However, as a number of European clubs declined participation in Copa Rio and their berths were given to less renowned ones, the quality of the eventually participating clubs was criticised in the Brazilian press,[15] therefore the Brazilian FA announced that the following editions of Copa Rio were not to be hailed as a World Champions Cup but only as Copa Rio,[16] and thus the second edition of the cup, won by Fluminense in 1952, was hailed as a World Champions Cup by a minority of the Brazilian press,[17][18] having Copa Rio been extinguished by the Brazilian FA soon later, and replaced with another cup, won in 1953 by Vasco da Gama.

Still in the 1950s, the Pequeña Copa del Mundo (Spanish for Small World Cup) was a tournament held in Venezuela between 1952 and 1957, with some other club tournaments held in Caracas from 1958 onwards also often referred to by the name of the original 1952–1957 tournament.[19] It was usually played by four participants, with two from Europe and two from South America.[19]

In 1960, FIFA authorised the International Soccer League, created along the lines of the 1950s Copa Rio, with a view to creating a Club World Cup, with ratification from Stanley Rous, who then had become FIFA president.[20] In the same year, the Intercontinental Cup rose to existence.

The Intercontinental Cup and early proposals for a FIFA Club World Cup

We want to win the title, not so much for ourselves but to prevent Racing from being champions.

—Jock Stein, Celtic Football Club's manager, 1965–1978, commenting before the play-off match of the 1967 Intercontinental Cup known as The Battle of Montevideo; Evening Times, 3 November 1967.[21]

The Dutch team AFC Ajax claimed a victory without any problems and this match was no more difficult than a banal encounter at the European Cup.

—A Dutch newspaper journalist from Amsterdam, commenting on the quality of the competition and Ajax's opponent after the 1972 Intercontinental Cup; De Telegraaf, 30 September 1972.[22]

The indifference of the fans is the only explanation for our financial failure [at the Intercontinental Cup]. It would be much better if we had gotten a friendly similar to the one we would do in Tel Aviv, on 11 January, for US$255,000.

—Dettmar Cramer, Bayern Munich's manager, 1975–1977, commenting on the low relevance, prestige and rewards of the Intercontinental Cup after his team's victory in 1976; Jornal do Brasil, 22 December 1976.[23]

The Tournoi de Paris was a competition initially meant to bring together the top teams from Europe and South America; it was first played in 1957 when Vasco da Gama, the Rio de Janeiro champions, beat European champions Real Madrid 4–3 in the final at the Parc des Princes. The match was the first ever hailed as the "best of Europe X best of South American" club match, as it was Real Madrid's first intercontinental competition as European champions (the Madrid team played the 1956 Pequeña Copa del Mundo, but confirmed their participation in the Venezuelan tournament before becoming European champions).[24] In 1958, Real Madrid declined to participate in the Paris competition claiming that the final of the 1957–58 European Cup was just five days after the Paris Tournoi.[25] On 8 October 1958, the Brazilian FA President João Havelange announced, at a UEFA meeting he attended as an invitee, the decision to create the "best of Europe X best of South American" club contest with endorsement from UEFA and CONMEBOL: the Copa Libertadores, the CONMEBOL-endorsed South American equivalent of the UEFA-endorsed European Cup, and the Intercontinental Cup, the latter being a UEFA/CONMEBOL-endorsed "best club of the world" contest between the champion clubs of both confederations.

Real Madrid won the first Intercontinental Cup in 1960,[26][27] titled themselves world champions until FIFA stepped in and objected; citing that the competition did not grant the right to attempt participation to any other champions from outside Europe and South America, FIFA stated that they can only claim to be intercontinental champions of a competition played between two continental organisations[28] (in contrast to the Intercontinental Cup, the right to attempt participation at the FIFA World Cup, through FIFA invitation in 1930 and qualification process since 1934, was open to every FIFA member-country, regardless of the continent where it was located). FIFA stated that they would prohibit the 1961 edition to be played out unless the organisers regarded the competition as a friendly or a private match between two organisations.[29]

The Intercontinental Cup attracted the interest of other continents.[30] The North and Central America confederation, CONCACAF, was created in 1961 in order to, among other reasons, try to include its clubs in the Copa Libertadores and, by extension, the Intercontinental Cup.[31] However, their entry into both competitions was rejected. Subsequently, the CONCACAF Champions' Cup began in 1962.[32]

Due to the brutality of the Argentine and Uruguayan clubs at the Intercontinental Cup, FIFA was asked several times during the late 1960s to assess penalties and regulate the tournament.[33] However, FIFA refused each request.[34] The first of these requests was made in 1967, after a play-off match labelled The Battle of Montevideo.[35] The Scottish Football Association, via President Willie Allan, wanted FIFA to recognise the competition in order to enforce football regulation; FIFA responded that it could not regulate a competition it did not organise.[21] Allan's crusade also suffered after CONMEBOL, with the backing of its President Teofilo Salinas and the Argentine Football Association (Asociación del Fútbol Argentino; AFA), refused to allow FIFA to have any hand in the competition stating:[36]

The CSF is the entity in charge of controlling, in South America, the organisation of the tournament between the champions of Europe and [South] America, a competition FIFA considers a friendly. We do not think it's appropriate that FIFA has to meddle in the matter.

René Courte, FIFA's General Sub-Secretary, wrote in 1967 an article shortly afterwards stating that FIFA viewed the Intercontinental Cup as a "European-South American friendly match".[37] This was confirmed by FIFA president Stanley Rous. With the Asian and North American club competitions in place in 1967, FIFA opened the idea of supervising the Intercontinental Cup if it included those confederations, with Stanley Rous saying that CONCACAF and the Asian Football Confederation had requested in 1967 participation of their champions in the Intercontinental Cup; the proposal was met with a negative response from UEFA and CONMEBOL. The 1968 and 1969 Intercontinental Cups finished in similarly violent fashion, with Manchester United manager Matt Busby insisting that "the Argentineans should be banned from all competitive football. FIFA should really step in."[38] In 1970, the FIFA Executive Committee proposed the creation of a multicontinental Club World Cup, not limited to Europe and South America but including also the other confederations; the idea did not go forward due to UEFA resistance.

In 1973, French newspaper L'Equipe, who helped bring about the birth of the European Cup,[39] volunteered to sponsor a Club World Cup contested by the champions of Europe, South America, North America and Africa, the only continental club tournaments in existence at the time; the competition was to potentially take place in Paris between September and October 1974, with an eventual final to be held at the Parc des Princes. The extreme negativity of the Europeans prevented this from happening.[40] The same newspaper tried once again in 1975 to create a Club World Cup, in which participants would have been the four semi-finalists of the European Cup, both finalists of the Copa Libertadores, as well as the African and Asian champions; once more, the proposal was to no avail.[41] UEFA, via its president, Artemio Franchi, declined once again and the proposal failed.[42] The idea for a multicontinental, FIFA-endorsed Club World Cup was also endorsed by João Havelange in his campaigning for FIFA presidency in 1974. The Mexican clubs América and Pumas UNAM, and the Mexican Football Association, demanded participation in the Intercontinental Cup (either as the American-continent representantives in the Intercontinental Cup or as part of a UEFA-CONMEBOL-CONCACAF new Intercontinental Cup) after winning the 1977–78 and 1980–81 editions of the Interamerican Cup against the South American champions; the request was unsuccessful.

The 1970s saw no fewer than seven occasions in which the European champions relinquished participating at the Intercontinental Cup, resulting in either the participation of the European Cup runners-up or the cancellation of the event; thus, with the Intercontinental Cup in danger of being dissolved,[43] West Nally, a British marketing company, was hired by UEFA and CONMEBOL to find a viable solution in 1980;[44][45][46] Toyota Motor Corporation, via West Nally, took the competition under its wing and rebranded it as the Toyota Cup, a one-off match played in Japan.[47][48] Toyota invested over US$700,000 in the 1980 edition to take place in Tokyo's National Olympic Stadium, with over US$200,000 awarded to each participant.[49] The Toyota Cup, with its new format, was received with scepticism, as the sport was unfamiliar in the Far East.[50][51] However, the financial incentive was welcomed, as European and South American clubs were suffering financial difficulties.[52] To protect themselves against the possibility of European withdrawals, Toyota, UEFA and every European Cup participant signed annual contracts requiring the eventual winners of the European Cup to participate at the Intercontinental Cup, as a condition UEFA stipulated to the clubs' participation in the European Cup, or risk facing an international lawsuit from UEFA and Toyota. For instance, Barcelona, the winners of the 1991–92 European Cup, considered not participating in the Intercontinental Cup in 1992, and the aforementioned contractual obligation weighed in for their decision to play.[53] In 1983, the English Football Association tried organising a Club World Cup to be played in 1985 and sponsored by West Nally, only to be denied by UEFA.[54]

Inauguration (2000–2001)

Manchester United see this as an opportunity to compete for the ultimate honour of being the very first world club champions.

—Martin Edwards, Manchester United's chairman, 1980–2002, commenting on the FIFA Club World Championship; British Broadcasting Corporation News, 30 June 1999.[55]

The framework of the 2000 FIFA Club World Championship was laid years in advance.[56] According to Sepp Blatter, the idea of the tournament was presented to the executive committee in December 1993 in Las Vegas, United States by Silvio Berlusconi, AC Milan's president.[57] Since every confederation had, by then, a stable, continental championship, FIFA felt it was prudent and relevant to have a Club World Championship tournament. Initially, there were nine candidates to host the competition: China, Brazil, Mexico, Paraguay, Saudi Arabia, Tahiti, Turkey, the United States and Uruguay; of the nine, only Saudi Arabia, Mexico, Brazil and Uruguay confirmed their interest to FIFA. On 7 June 1999, FIFA selected Brazil to host the competition,[58] which was initially scheduled to take place in 1999.[59] Manchester United legend Bobby Charlton, a pillar of England's victorious campaign in the 1966 FIFA World Cup, stated that the Club World Championship provided "a fantastic chance of becoming the first genuine world champions."[60] The competition gave away US$28 million in prize money and its TV rights, worth US$40 million, were sold to 15 broadcasters across five continents.[61] The final draw of the first Club World Championship was done on 14 October 1999 at the Copacabana Palace Hotel in Rio de Janeiro.[62]

There they were claiming that the English weren't interested in the world championship, yet the BBC sent 60 people to cover the tournament. This shows that it was the most important competition that they have taken part in in their history. They came here thinking they were going to win easily but they didn't count on the strength of Vasco. No Manchester player would get a place in the Vasco team at the moment. The Brazilians are the best players in the world, the Europeans do not even come close.

—Eurico Miranda, Vasco da Gama's vice-president, 1986–2000, commenting on the importance given to the tournament by the British news media, the level of European club football as well as Brazil's after his side's 3–1 win over Manchester United; Independent Online, 11 January 2000.[63]

The inaugural competition was planned to be contested in 1999 by the continental club winners of 1998, the Intercontinental Cup winners and the host nation's national club champions, but it was postponed by one year. When it was rescheduled, the competition had eight new participants from the continental champions of 1999: Brazilian clubs Corinthians and Vasco da Gama, English side Manchester United, Mexican club Necaxa, Moroccan club Raja CA, Spanish side Real Madrid, Saudi club Al-Nassr, and Australian club South Melbourne.[64] The first goal of the competition was scored by Real Madrid's Nicolas Anelka against Al-Nassr; Real Madrid went on to win the match 3–1.[65] The final was an all-Brazilian affair, as well as the only one which saw one side have home advantage.[66] Vasco da Gama could not take advantage of its local support, being beaten by Corinthians 4–3 on penalties after a 0–0 draw in 90 minutes and extra time.[67][68]

The second edition of the competition was planned for Spain in 2001, and would have featured 12 clubs.[69] The draw was performed at A Coruña on 6 March 2001.[70] However, it was cancelled on 18 May, due to a combination of factors, most importantly the collapse of FIFA's marketing partner International Sport and Leisure.[71] The participants of the cancelled edition received US$750,000 each in compensation; the Real Federación Española de Fútbol (RFEF) also received US$1 million from FIFA.[72] Another attempt to stage the competition in 2003, in which 17 countries were looking to be the host nation, also failed to happen.[73][74] FIFA agreed with UEFA, CONMEBOL and Toyota to merge the Intercontinental Cup and Club World Championship into one event.[75] The final Intercontinental Cup, played by representatives clubs of most developed continents in the football world, was in 2004, with a relaunched Club World Championship held in Japan in December 2005.[76] All the winning teams of the Intercontinental Cup were regarded by worldwide mass media and football's community as de facto "world champions"[77][78][79] until 2017 when FIFA officially (de jure) recognised all of them as official club world champions in equal status to the FIFA Club World Cup winners.[80][81]

Knock-out tournaments (2005–present)

The 2005 version was shorter than the previous World Championship, reducing the problem of scheduling the tournament around the different club seasons across each continent. It contained just the six reigning continental champions, with the CONMEBOL and UEFA representatives receiving byes to the semi-finals. A new trophy was introduced replacing the Intercontinental trophy, the Toyota trophy and the trophy of 2000. The draw for the 2005 edition of the competition took place in Tokyo on 30 July 2005 at The Westin Tokyo.[82] The 2005 edition saw São Paulo pushed to the limit by Saudi side Al-Ittihad to reach the final.[83] In the final, one goal from Mineiro was enough to dispatch English club Liverpool;[84] Mineiro became the first player to score in a Club World Cup final.[85]

Internacional defeated defending World and South American champions São Paulo in the 2006 Copa Libertadores Finals in order to qualify for the 2006 tournament.[86] At the semi-finals, Internacional beat Egyptian side Al Ahly in order to meet Barcelona in the final.[87] A late goal from Adriano Gabiru kept the trophy in Brazil.[88][89] It was in 2007 when Brazilian hegemony was finally broken: AC Milan won a close match against Japan's Urawa Red Diamonds, who were pushed by over 67,000 fans at Yokohama's International Stadium, and won 1–0 to reach the final.[90] In the final, Milan crushed Boca Juniors 4–2, in a match that saw the first player sent off in a Club World Cup final: Milan's Kakha Kaladze from Georgia in the 77th minute.[91] Eleven minutes later, Boca Junior's Pablo Ledesma would join Kaladze as he too was sent off.[92] The following year, Manchester United would emulate Milan by beating their semi-final opponents, Japan's Gamba Osaka, 5–3.[93] They saw off Ecuadorian club LDU Quito 1–0 to become world champions in 2008.[94][95]

United Arab Emirates successfully applied for the right to host the FIFA Club World Cup in 2009 and 2010.[96] Barcelona dethroned World and European champions Manchester United in the 2009 UEFA Champions League Final to qualify for the 2009 Club World Cup.[97] Barcelona beat Mexican club Atlante in the semi-finals 3–1 and met Estudiantes in the final.[98] After a very close encounter which saw the need for extra-time, Lionel Messi scored from a header to snatch victory for Barcelona and complete an unprecedented sextuple.[99][100][101][102][103] The 2010 edition saw the first non-European and non-South American side to reach the final: TP Mazembe from the Democratic Republic of Congo defeated Brazil's Internacional 2–0 in the semi-final to face Internazionale, who beat South Korean club Seongnam Ilhwa Chunma 3–0 to reach the final.[104][105] Internazionale went on to beat Mazembe with the same scoreline to complete their quintuple.[106][107]

The FIFA Club World Cup returned to Japan for the 2011 and 2012 editions.[108] In 2011, Barcelona comfortably won their semi-final match 4–0 against Qatari club Al Sadd.[109] In the final, Barcelona won against Santos by the same scoreline for their second title.[110] Messi also became the first player to score in two different Club World Cup finals.[111] The 2012 edition saw Europe's dominance come to an end as Corinthians, boasting over 30,000 travelling fans which was dubbed the "Invasão da Fiel", travelled to Japan to join Barcelona in being two-time winners of the competition.[112][113] In the semi-finals, Al-Ahly managed to keep the scoreline close as Corinthians' Paolo Guerrero scored to send the Timão into their second final.[114] Guerrero would once again come through for Corinthians as the Timão saw off English side Chelsea 1–0 in order to bring the trophy back to Brazil.[67][115]

2013 and 2014 had the Club World Cup moving to Morocco. The first edition saw a Cinderella run of host team Raja CA, who had to start in the play-off round and became the second African team to reach the final, after defeating Brazil's Atlético Mineiro in the semi-final.[116] Like Mazembe, Raja also lost to the European champion, this time a 2–0 defeat to Bayern Munich.[117] 2014 again had a decision between South America and Europe, and Real Madrid beat San Lorenzo 2–0.[118]

The 2015 and 2016 editions once again saw Japan as hosts for the 7th and 8th time respectively in the 12th and 13th editions of the FIFA Club World Cup. The 2015 edition saw a final between River Plate and FC Barcelona. FC Barcelona lifted their third FIFA Club World Cup, with Suarez scoring two goals and Lionel Messi scoring one goal in the Final. One notable thing that occurred in the 2015 tournament was that Sanfrecce Hiroshima made it to third place, the farthest ever achieved by a Japanese club. This record would not last though, as the 2016 edition saw J1 League winners Kashima Antlers making it to the Final (outscoring rivals 7–1), against Real Madrid. A Gaku Shibasaki inspired Kashima attempted to win their first FIFA Club World Cup (a feat never done by any club outside of Europe and South America), but were denied by Real Madrid, who won 4–2 in extra time, thanks to a hat-trick by Cristiano Ronaldo.[119]

The UAE returned to host the event in 2017 and 2018.[120][121] 2017 involved the likes of Real Madrid becoming the first team in Club World Cup history to return to the tournament to defend their title. Real Madrid became the first team to successfully defend their title after defeating Grêmio in the Final, all while eliminating Al Jazira in the Semi-Finals. Al-Ain was the first Emirati team to reach the Club World Cup final,[122] as well as the second Asian team to reach the final in the 2018 edition. Real Madrid defeated Al-Ain 4–1 in the final, to win their fourth title in the competition and to become the first team ever to win it three years in a row and four times in total in the tournament's history. Thus, Real Madrid extended their international titles to seven after winning the 2018 edition (counting their three Intercontinental Cup titles and four Club World Cup titles).[n 1]

On 3 June 2019, FIFA selected Qatar as the host of both the 2019 and 2020 events.[124][125] Gonzalo Belloso, the Deputy Secretary General and development director of CONMEBOL, previously said that the 2019 and 2020 editions will be held in Japan.[126] The 2019 edition saw Liverpool defeat Flamengo to win the competition for the first time.[127] In the 2020 edition, Bayern Munich beat Tigres UANL 1–0, completing their sextuple.[128] The 2021 tournament was won by Chelsea, who defeated Palmeiras 2–1 after extra time for their first title.[129]

Expansion

In late 2016, FIFA President Gianni Infantino suggested an expansion of the Club World Cup to 32 teams beginning in 2019 and the reschedule to June to be more balanced and more attractive to broadcasters and sponsors.[130] In late 2017, FIFA discussed proposals to expand the competition to 24 teams and have it be played every four years by 2021, replacing the FIFA Confederations Cup.[131]

The new tournament with 24 teams was supposed to start in 2021 and would have included all UEFA Champions League winners, UEFA Champions League runners-up, UEFA Europa League winners, and Copa Libertadores winners from the four seasons up to and including the year of the event, with the remainder qualifying from the other four confederations.[132][133] Along with a new UEFA Nations League competition, revenues of $25 billion would be expected during the period from 2021 to 2033.[134] The first tournament would have been played in China; however, the tournament was cancelled[135] due to scheduling issues caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.[136]

On 16 December 2022, FIFA announced an expanded tournament that would have 32 teams and start in June 2025.[135][137][138] The International Federation of Professional Footballers and World Leagues Forum both immediately criticized the proposal.[135] On 23 June 2023, FIFA confirmed that the United States will host the 2025 tournament as a prelude to the 2026 FIFA World Cup.[139] The 32 teams will be divided into 8 groups of 4 teams with the top 2 teams in each group qualifying to the knockout stage. The FIFA Council also unanimously approved the concept of an annual club competition from 2024, called the FIFA Intercontinental Cup, in response to the fact that the FIFA Club World Cup was last held in its previous guise in 2023.[140]

The format of the tournament has caused controversy, with many clubs and national associations opposing its scheduling and accusing FIFA of prioritizing money over players' health,[141] arguing that the addition of the new FIFA Intercontinental Cup could lead to competition overload and put players' health at risk.[142][143]

Results

Finals

- Notes

- ^ The council of FIFA officially recognizes the winners of the Intercontinental Cup and the FIFA Club World Cup as club world champions.[123]

- ^ a b c d e f g No extra time was played.

- ^ Score was 1–1 after 90 minutes.

- ^ Score was 2–2 after 90 minutes.

- ^ Score was 0–0 after 90 minutes.

- ^ Score was 1–1 after 90 minutes.

Performances by club

| Club | Titles | Runners-up | Years won | Years runners-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0 | 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2022 | — | |

| 3 | 1 | 2009, 2011, 2015 | 2006 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2000, 2012 | — | |

| 2 | 0 | 2013, 2020 | — | |

| 1 | 1 | 2019 | 2005 | |

| 1 | 1 | 2021 | 2012 | |

| 1 | 0 | 2005 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 2006 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 2007 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 2008 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 2010 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 2023 | — | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2000 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2007 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2008 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2009 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2010 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2011 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2013 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2014 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2015 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2016 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2017 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2018 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2019 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2020 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2021 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2022 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2023 |

Performances by country

| Country | Titles | Runners-up | Years won | Years runners-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1 | 2009, 2011, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2022 | 2006 | |

| 4 | 6 | 2000, 2005, 2006, 2012 | 2000, 2011, 2017, 2019, 2021, 2023 | |

| 4 | 2 | 2008, 2019, 2021, 2023 | 2005, 2012 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2007, 2010 | — | |

| 2 | 0 | 2013, 2020 | — | |

| 0 | 4 | — | 2007, 2009, 2014, 2015 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2008 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2010 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2013 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2016 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2018 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2020 | |

| 0 | 1 | — | 2022 |

Performances by confederation

Africa's best representatives were TP Mazembe from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Moroccan club Raja CA, which finished second in 2010 and 2013, respectively. Asia's best representatives were Kashima Antlers from Japan, Al-Ain from the United Arab Emirates and Al-Hilal from Saudi Arabia, finishing second in 2016, 2018 and 2022, respectively. North America's best result was Mexican team Tigres UANL, which earned a second-place finish in 2020. These six clubs are the only sides from outside Europe and South America to reach the final.

Auckland City from New Zealand earned third place in 2014, the only time to date that an Oceanian team reached the semi-finals of the tournament.

| Confederation | Winners | Runners-up | Third place |

|---|---|---|---|

| UEFA | 16 | 3 | — |

| CONMEBOL | 4 | 11 | 5 |

| AFC | — | 3 | 5 |

| CAF | — | 2 | 4 |

| CONCACAF | — | 1 | 5 |

| OFC | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 20 | 20 | 20 |

Format and rules

| Play-off round | |

|---|---|

| |

| Quarter-final round | |

| |

| Semi-final round | |

| |

| Final | |

|

As of 2022, most teams qualify to the FIFA Club World Cup by winning their continental competitions, be it the AFC Champions League, CAF Champions League, CONCACAF Champions League, Copa Libertadores, OFC Champions League or UEFA Champions League. Aside from these, the host nation's national league champions qualify as well.[186]

The maiden edition of this competition was separated into two rounds. The eight participants were split into two groups of four teams. The winner of each group met in the final while the runners-up played for third place. The competition changed its format during the 2005 relaunch into a single-elimination tournament in which teams play each other in one-off matches, with extra time and penalty shoot-outs used to decide the winner if necessary. It featured six clubs competing over a two-week period. There were three stages: the quarter-final round, the semi-final round and the final. The quarter-final stage pitted the Oceanian Champions League winners, the African Champions League winners, the Asian Champions League winners and the North American Champions League winners against each other. Afterwards, the winners of those games would go on to the semi-finals to play the European Champions League winners and South America's Copa Libertadores winners. The victors of each semi-final would play go on to play in the final.[186]

With the introduction of this format, a fifth place match and a spot for the host nation's national league champions were added. There are now four stages: the play-off round, the quarter-final round, the semi-final round and the final. The first stage pits the host nation's national league champions against the Oceanian Champions League winners. The winner of that stage would go on the quarter-finals to join the African Champions League winners, the AFC Champions League winners and the CONCACAF Champions League winners. The winners of those games would go on to the semi-finals to play the UEFA Champions League winners and South America's Copa Libertadores winners. The winners of each semi-final play each other in the final.[186]

Starting from 2022, the match for fifth place is no longer played.[185]

Trophy

The trophy used during the inaugural competition was called the FIFA Club World Championship Cup. The original laurel was created by Sawaya & Moroni, an Italian designer company that produces contemporary designs with cultural backgrounds and design concepts. The designing firm is based in Milan. The fully silver-coloured trophy had a weight of 4 kg (8.8 lb) and a height of 37.5 cm (14.8 in). Its base and widest points are 10 cm (3.9 in) long. The trophy had a base of two pedestals which had four rectangular pillars. Two of the four pillars had inscriptions on them; one contained the phrase, "FIFA Club World Championship" imprinted across. The other had the letters "FIFA" inscribed on it. On top, a football based on the 1998 FIFA World Cup ball, the Adidas Tricolore, can be seen. The production costs of the laurel was US$25,000. It was presented for the first time at Sheraton Hotels and Resorts in Rio de Janeiro on 4 January 2000.[187][188][189][190]

Just as the [FIFA] women's [World Cup] trophy had a distinct feminine note to it, so this new trophy is more masculine. It is also inspired by a classic sense of geometry and architecture, enduring concepts just like the status of a World Champion.

William Sawaya, designer of the FIFA Club World Championship trophy, commenting on the laurel; Fédération Internationale de Football Association, 3 January 2000.[187]

The tournament, in its second format, shared its name with the second trophy, also called the FIFA Club World Cup or simply la Copa, which was awarded to the FIFA Club World Cup winner. It was unveiled at Tokyo on 30 July 2005 during the draw of that year's edition of the competition. The laurel was designed in 2005 in Birmingham, United Kingdom, at Thomas Fattorini Ltd, by English designer Jane Powell, alongside her assistant Dawn Forbes, at the behest of FIFA. The gold-and-silver-coloured trophy, weighing 5.2 kg (11 lb), had a height of 50 cm (20 in). Its base and widest points were also measured at exactly 20 cm (7.9 in). It was made out of a combination of brass, copper, sterling silver, gilding metal, aluminium, chrome and rhodium. The trophy itself was gold plated.[82][188]

The design, according to FIFA, showed six staggered pillars, representing the six participating teams from the respective six confederations, and one separate metal structure referencing the winner of the competition. They held up a globe in the shape of a football – a consistent feature in almost all of FIFA's trophies. The golden pedestal had the phrase, "FIFA Club World Cup", imprinted at the bottom.[188]

As part of the expansion of the tournament to 32 teams, a new trophy was created in collaboration with global luxury jeweller Tiffany & Co. and unveiled on 14 November 2024. The new trophy features a 24-carat gold-plated finish, intricate laser-engraved inscriptions on both sides including a world map and the names of all 211 FIFA member associations and the six confederations, icons that capture football's traditions, including symbols of stadiums and equipment, and engravings in 13 languages and braille. Space is available to laser-engrave the emblems of the winning clubs for 24 editions of the tournament. The trophy can transform from a shield into a multifaceted and orbital structure.[191] The deisgn was inspired by the Voyager Golden Records.

Awards

At the end of each Club World Cup, awards are presented to the players and teams for accomplishments other than their final team positions in the tournament. There are currently three awards:[192]

- The Golden Ball for the best player, determined by a vote of media members, who is also awarded the Alibaba Cloud Award (the presenting sponsor of the FIFA Club World Cup); the Silver Ball and the Bronze Ball are awarded to the players finishing second and third in the voting respectively.[192]

- The Player of the Match (formerly known as the "Man of the Match") for the best performing player in each tournament match. It was first awarded in 2013.

- The FIFA Fair Play Trophy for the team with the best fair play record, according to the points system and criteria established by the FIFA Fair Play Committee.[192]

The winners of the competition are also entitled to receive the FIFA Champions Badge; it features an image of the trophy, which the reigning champion is entitled to display on its first-team kit only, up until and including, the final of the next championship. The first edition of the badge was presented to Milan, the winners of the 2007 final.[193][194] All four previous champions were allowed to wear the badge until the 2008 final, where Manchester United gained the sole right to wear the badge by winning the trophy.[195]

Each tournament's top three teams receives a set of gold, silver or bronze medals to distribute to their players.[192]

Prize money

| Winners | $5 million |

| Runners-up | $4 million |

| Third place | $2.5 million |

| Fourth place | $2 million |

| Fifth place | $1.5 million |

| Sixth place | $1 million |

| Seventh place | $0.5 million |

The 2000 FIFA Club World Championship was the inaugural edition of this competition; it provided US$28 million in prize money for its participants. The prize money received by the clubs participating was divided into fixed payments based on participation and results. Clubs finishing the tournament from fifth to eighth place received US$2.5 million. The club who would eventually finish in fourth place received US$3 million while the third-place team received US$4 million. The runner-up earned US$5 million while the eventual champions would gain US$6 million.[196]

The relaunch of the tournament in 2005 FIFA Club World Championship saw different amounts of prize money given and some changes in the criteria of receiving certain amounts. The total amount of prize money given dropped to US$16 million. The winners received US$5 million and the runners-up US$4 million, with $2.5 million for third place, US$2 million for fourth, US$1.5 million for fifth and US$1 million for sixth.[197]

For the 2007 FIFA Club World Cup, a play-off match between the OFC champions and the host-nation champions for entry into the quarter-final stage was introduced in order to increase home interest in the tournament. The reintroduction of the match for fifth place for the 2008 competition also prompted an increase in prize money by US$500,000 to a total of US$16.5 million.[198]

Sponsorship

Like the FIFA World Cup, the FIFA Club World Cup is sponsored by a group of multinational corporations. Toyota Motor Corporation, a Japanese multinational automaker headquartered in Toyota, Aichi, was the Presenting Partner of the FIFA Club World Cup until its sponsorship agreement expired at the end of December 2014 and was not renewed.[199]

In 2015, Alibaba Group signed an eight-year contract to become the Presenting Partner of the competition.[200]

The inaugural competition had six event sponsors: Fujifilm, Hyundai, JVC, McDonald's, Budweiser and MasterCard.[201]

Individual clubs may wear jerseys with advertising, even if such sponsors conflict with those of the FIFA Club World Cup. However, only one main sponsor is permitted per jersey in addition to that of the kit manufacturer.[186]

Records and statistics

Toni Kroos has won the FIFA Club World Cup six times, the most titles for any player.[202] Cristiano Ronaldo is the overall top scorer in FIFA Club World Cup history, with seven goals.[203] Hussein El Shahat has made the most appearances in the competition, with fifteen.[204]

Real Madrid have won the FIFA Club World Cup a record five times. They also have the most wins (12) and most total goals scored in the competition (40).[205][206] Auckland City have participated in the most editions of the tournament (11), while Al Ahly have played the most overall matches (25).[206]

Official songs

Like most international football tournaments, the FIFA Club World Cup has featured official songs for each tournament since 2005.

| Year | Hosts | Official songs/anthems | Languages(s) | Performer(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | "Legendary Meadow" | Japanese | Chemistry | |

| 2006 | "Top of the World" | Japanese | ||

| 2007 | "Shining Night" | Japanese | Chemistry (supported by Monkey Majik) | |

| 2008 | "Septenova" | English and Japanese | Gospellers vs. Shintaro Tokita (from Sukima Switch) | |

| 2009 | "The River Sings" | Loxian | Enya | |

| 2010 | ||||

| 2011 | "Never Give Up" | Japanese | Kylee | |

| 2012 | "World Quest" | Japanese | NEWS | |

| 2013 | "Seven Colors" | English and Japanese | ||

| 2014 | ||||

| "Come Alive" | English | RedOne feat. Chawki | ||

| 2015 | "Anthem" | English | NEWS | |

| 2016 | ||||

| 2017 | "Kingdom" | English and Japanese | ||

| 2018 | "Spirit" | Japanese | ||

| 2019 | "Superstar" | Japanese | ||

| 2022 | "Welcome To Morocco" | English and Arabic | RedOne, Douzi, Hatim Ammor, Asma Lamnawar, Rym, Aminux, Nouaman Belaiachi, Zouhair Bahaoui, Dizzy DROS | |

| 2023 | "It's On"[207] | English | Bebe Rexha, RedOne |

Reception

Since its inception in 2000, the competition, despite its name and the contestants' achievements, has received differing reception. In most of Europe it struggles to find broad media attention compared to the UEFA Champions League and commonly lacks recognition as a high-ranking contest.[208][209] In South America, however, it is widely considered the highest point in the career of a footballer, coach and/or team at international club level.[210][211]

The competition is also criticised, mainly by the European press and fans among others, for its format, which favours the UEFA and CONMEBOL teams, since their representatives start in the semi-finals and can only meet each other in the final match.[citation needed] The opening up of the global market in football has changed the balance. Nowadays, the best South Americans are usually playing for the European teams.[212][213] FIFA's decision to choose the competition's host based on financial factors rather than footballing ones, as in the case of Qatar, has also been criticised.[214] Additionally, the economic benefits to the winning team are considered inferior to any Super Cup prizes.[215][216]

List of current broadcasters

| Territory | Rights holder | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | Meraj TV, Solh TV | [217] |

| Azerbaijan | CBC Sport | [217] |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Arena Sport | [217] |

| Brazil | [218][219] | |

| Bulgaria | Max Sport | [217] |

| Central Asia | Match! TV | [217] |

| Croatia | Arena Sport | [217] |

| Czech Republic | Nova Sport | [217] |

| France | Canal+, L'Equipe TV | [220] |

| Hungary | M4 Sport | [217] |

| India | Eurosport India, FanCode | [218][219] |

| Iran | IRIB Varzesh, Perisiana Sports | [220] |

| Ireland | LiveScore | [221] |

| Italy | Sky Italia | [220] |

| Kazakhstan | Qazsport TV | [220] |

| Malaysia | SPOTV | [220] |

| MENA | Saudi Sports Company | [217] |

| Portugal | Sport TV | [217] |

| Russia | Match! TV | [217] |

| Serbia | Arena Sport | [217] |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | StarTimes Sports | [217] |

| Tajikistan | TV Varzish, TV Football | [217] |

| Turkey | TV8, Exxen | [217] |

| Ukraine | Megogo Futbol | [217] |

| United States | Fox Sports | [222] |

| United Kingdom | TNT Sports | [217] |

| Uzbekistan | Sport Uzbekistan | [217] |

| Worldwide | FIFA+ | [217] |

See also

References

- ^ Vickery, Tim (15 December 2008). "The prestige of the Club World Cup". BBC Sport. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Vickery, Tim (16 December 2014). "Club World Cup: Real Madrid ahead for San Lorenzo". BBC Sport. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Campo, Carlo (27 October 2017). "FIFA recognises all winners of Intercontinental Cup as club world champions". theScore. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ a b Jonathan Wilson (25 April 2020). "Sunderland's Victorian all-stars blazed trail for money's rule of football". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "When Sunderland AFC Were World Champions!". Ryehill Football. 19 August 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Maintaining the Corporate Image". FIFA. 17 June 1998. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "The History of Football". FIFA. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "West Auckland AFC statue to mark Sir Thomas Lipton Trophy win". BBC. 23 September 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Veronese, Andrea (20 November 2004). "Sir Thomas Lipton Trophy (Torino)". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Importantes Declaraciones de Mr. Jules Rimet, presidente de la F.I.F.A" [Important declarations from Mr. Jules Rimet, FIFA President]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 5 April 1951. p. 3. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Corriere dello Sport: Claudio Carsughi – Tra Rio de Janeiro e San Paolo l´avvio del "Torneo dei Campioni" – página 3(acervo), 30 June 1951

- ^ "O ESTADO DE S. PAULO: PÁGINAS DA EDIÇÃO DE 26 DE Junho DE 1962". O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). 26 June 1962. p. 11. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Superheroes in green". FIFA. 10 February 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Bernardi, Bruno (30 June 1975). "Parola ed Altafini sarà una tournée piena di ricordi e nostalgie" [Parola and Altafini will make this a nostalgic tournament to remember]. La Stampa (in Italian). p. 10. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "O Estado de S. Paulo - Acervo Estadão". Acervo. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "O Estado de S. Paulo - Acervo Estadão". Acervo. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Mundo Esportivo (Brazilian newspaper), 9 March 1956, page 15, edition 745.

- ^ Jornal dos Sports (Brazilian newspaper), 21 August 1952, page 5. Edition 7050.

- ^ a b Stokkermans, Karel; Varanda, Pedro (19 August 2010). "Pequeña Copa del Mundo and Other International Club Tournaments in Caracas". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "O ESTADO DE S. PAULO: PÁGINAS DA EDIÇÃO DE 24 DE Maio DE 1961". O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). 24 May 1961. p. 17. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Stein gives a pledge before ... Feud in the Sun, "We'll give as much as we take"". Evening Times. 3 November 1967. p. 24. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Cruyff: "Demasiada lentitud de los argentinos en sus ofensivas"" [Cruyff: "The Argentine offensive is way too slow"]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 30 September 1972. p. 13. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Taça não interessa mais aos alemães" [The tournament holds no interest from the Germans]. Jornal do Brasil (in Portuguese). 22 December 1976. p. 20. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Vasco tentará reconhecimento de título mundial de 1957" [Vasco will try to get recognition for the 1957 world title]. Super Vasco (in Portuguese). 15 June 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Ayer llego a Madrid el equipo Portuges Benfica que participara en la Copa Latina" [Yesterday, Benfica from Portugal arrived in Madrid to participate in the Latin Cup]. ABC (in Spanish). Madrid. 18 June 1957. p. 53. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Carluccio, Jose (2 September 2007). "¿Qué es la Copa Libertadores de América?" [What is the Copa Libertadores de América?]. Historia y Fútbol (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Goodbye Toyota Cup, hello FIFA Club World Championship". FIFA. 10 December 2004. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La Copa Intercontinental, un perro sin amo". Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Briordy, William (24 May 1961). "Bangu, Karlsruhe Play Tonight in Polo Grounds Soccer Game; Permission is Received by International League to Continue its Schedule". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "O ESTADO DE S. PAULO: PÁGINAS DA EDIÇÃO DE 15 DE Janeiro DE 1960". O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). 15 January 1960. p. 18. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "O ESTADO DE S. PAULO: PÁGINAS DA EDIÇÃO DE 20 DE Agosto DE 1961". O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). 20 August 1961. p. 29. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FC Internazionale Milano on top of the world" (PDF). UEFA. 1 February 2011. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La Copa Intercontinental de futbol debe ser oficial" [Football's Intercontinental Cup should be given official status]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 30 November 1967. p. 4. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "El proyecto de Copa del Mundo se discutira en Mejico" [The Club World Cup project will be discussed in Mexico]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 24 April 1970. p. 10. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La FIFA, no controla la Intercontinental" [FIFA does not control the Intercontinental Cup]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 3 November 1967. p. 6. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La FIFA rehuye el bulto" [FIFA shuns the bulge]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 25 November 1967. p. 8. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La Copa del Mundo Inter-clubs se amplia" [The Intercontinental Clubs' Cup will be amplified]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 25 February 1970. p. 13. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Estudiantes leave their mark". Entertainment and Sports Programming Network Football Club. 16 December 2010. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "European Cup: 50 Years" (PDF). UEFA. 25 October 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Una copa mundial de clubs con los campeones de Europa, Asia, Africa, Sudamerica y America Central" [A Club World Cup with the European, Asian, African, South American and Central American champions]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 29 November 1973. p. 4. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Una idea para los cinco campeones de cada continente" [An idea for the five continental champions]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 5 June 1975. p. 13. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Europa a desvalorizado la Copa Intercontinental" [Europe has devalued the Intercontinental Cup]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 10 April 1975. p. 15. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La Copa Intercontinental anda renqueante" [The Intercontinental Cup is ailing]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 6 August 1979. p. 16. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La final Intercontinental, en peligro" [The Intercontinental final, in danger]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 1 September 1980. p. 16. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La Copa Intercontinental ya tiene fechas" [The Intercontinental Cup has dates]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 24 September 1980. p. 13. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La final Intercontinental, a un partido y en Japon" [The Intercontinental final, one game in Japan]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 30 November 1980. p. 16. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La Intercontinental, en Tokio a un partido" [The Intercontinental Cup, one game in Tokyo]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 11 September 1980. p. 19. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Gray y Robertson no estarán en Valençia con el Nottingham" [Gray and Robertson will not be in Valencia with Nottingham]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 12 December 1980. p. 18. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Calvo, J. A. (12 February 1981). "El año de los Charruas" [The Charruan year]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). p. 19. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Nacional se queja del campo" [Nacional complains over the pitch]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 7 February 1981. p. 18. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Todo preparado para la Intercontinental" [Everything is prepared for the Intercontinental Cup]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 11 February 1981. p. 19. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "¿Debe ir el Nottingham a Tokio?" [Should Nottingham go to Tokyo?]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 4 February 1981. p. 19. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Aguilar, Francesc (18 September 1992). "La negociación será difícil" [Negotiations will be difficult]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). p. 8. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "No habra una Copa Mundial de Clubes" [There will not be a Club World Cup]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 23 November 1983. p. 20. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "United pull out of FA Cup". BBC. 30 June 1999. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "O ESTADO DE S. PAULO: PÁGINAS DA EDIÇÃO DE 16 DE Junho DE 1994". O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). 16 June 1994. p. 30. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Blatter: "The Club World Championship holds promise for the future"". FIFA. 6 December 1999. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Brasil recebe o primeiro mundial de clubes". Folha de S.Paulo (in Brazilian Portuguese). 8 June 1999. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Mundial de Clubs en 1999" [Club World Cup in 1999]. Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 3 September 1997. p. 42. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Charlton, Bobby (28 December 1999). "Um desafio fascinante" [A fascinating challenge] (PDF). Jornal do Brasil (in Portuguese). p. 21. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ "Alta definição" [High definition] (PDF). Jornal do Brasil (in Portuguese). 28 December 1999. p. 23. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ "Brazil 2000 Final Draw". FIFA. 14 October 1999. Retrieved 6 March 2013.[dead link]

- ^ "Reds in Rio to drink, taunts Gerson". Independent Online. 11 January 2000. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "Who will go down in history?". FIFA. 31 December 1999. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Real Madrid – Al Nassr". FIFA. 5 January 2000. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Corinthians – Vasco da Gama". FIFA. 14 January 2000. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Futebol: Titulos" [Football: Titles]. Sport Club Corinthians Paulista (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Corinthians crowned world champions". BBC News. 15 January 2000. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Stokkermans, Karel (31 December 2005). "2001 FIFA Club World Cup". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Galaxy to face Real, African and Asian teams". USA Today. 7 March 2001. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA decides to postpone 2001 Club World Championship to 2003". FIFA. 18 May 2001. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ "World Club Championship might grow". USA Today. 10 October 2001. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Davies, Christopher (18 May 2001). "FIFA postpone club cup". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Numerous interests in hosting 2003/2005 FIFA Club World Championships". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 10 May 2001. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Toyota confirmed as FIFA Club World Championship 2005 naming partner". FIFA. 15 March 2005. Retrieved 6 March 2013.[dead link]

- ^ "Logo revealed for top club competition". FIFA. 5 April 2005. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Walker, Joe (18 December 2016). "Ronaldo treble fires Madrid to Club World Cup glory". UEFA. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ "Maldini wants world title". UEFA. 10 December 2003. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Fédération Internationale de Football Association, ed. (18 December 2015). "Japan Aiming High" (PDF). The FIFA Weekly. No. 50. pp. 8–9. OCLC 862248672. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ "FIFA Council approves key organisational elements of the FIFA World Cup" (Press release). FIFA. 27 October 2017. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup UAE 2018: Statistical-kit" (PDF). 10 December 2018. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2021.

- ^ a b "FIFA Club World Championship TOYOTA Cup Japan 2005 trophy to be unveiled at Official Draw on 30 July in Tokyo". FIFA. 21 July 2005. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Al Ittihad – Sao Paulo FC". FIFA. 15 December 2005. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Conquistas" [Conquests]. São Paulo Futebol Clube (in Portuguese). Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Sao Paulo FC – Liverpool FC". FIFA. 18 December 2005. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Inter take title and a place in Japan". FIFA. 17 August 2006. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Al Ahly Sporting Club – Sport Clube Internacional". FIFA. 13 December 2006. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Inter, o melhor do mundo" [Inter, the best in the world]. Sport Club Internacional (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Sport Clube Internacional – FC Barcelona". FIFA. 17 December 2006. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Milan set up Boca showdown". FIFA. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup 2007". Associazione Calcio Milan (in Italian). Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Dominant Milan rule the world". FIFA. 16 December 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "United hit five in thriller". FIFA. 18 December 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Trophy Room". Manchester United Football Club. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Red Devils rule in Japan". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 21 December 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Unanimous support for 6+5, FIFA Club World Cup hosts revealed". FIFA. 27 May 2008. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Barça reign supreme". FIFA. 27 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Exceptional Barça reach final". FIFA. 16 December 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Palmarès" [Trophies]. Futbol Club Barcelona (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Barça belatedly rule the world". FIFA. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Liceras, Ángel (19 December 2012). "Recordando la temporada perfecta" [Remembering a perfect season]. Marca (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Barcelona beat Estudiantes to win the Club World Cup. BBC Sport. 19 December 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "The year in pictures". FIFA. Archived from the original on 31 December 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Inter stunned as Mazembe reach final". FIFA. 14 December 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Seongnam sunk as Inter stroll". FIFA. 15 December 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Palmares: Primo Mondiale per Club FIFA – 2010/11" [Trophies: First FIFA Club World Cup – 2010/11]. Football Club Internazionale Milano S.p.A. (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2 January 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Internazionale on top of the world". FIFA. 18 December 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Blatter reveals double boost for Japan". FIFA. 23 May 2011. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Adriano at the double as Barça cruise". FIFA. 15 December 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Santos humbled by brilliant Barcelona". FIFA. 18 December 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Lionel Messi". FIFA. Archived from the original on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "The Corinthian Invasion of Japan". FIFA. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 16 December 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Corinthians halt European domination". FIFA. 17 December 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Corinthians edge Al-Ahly to reach final". FIFA. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Guerrero the hero as Corinthians crowned". FIFA. 16 December 2012. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Hughes, Ian (13 December 2013). "Raja revel in historic victory". BBC. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Bayern Munich manager Pep Guardiola targets more silverware after Club World Cup victory". The Daily Telegraph. London. 22 December 2013. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ "Real Madrid beat San Lorenzo to take Club World Cup crown". ESPN. 22 December 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Madrid see off spirited Kashima in electric extra time final". FIFA. 18 December 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ “UAE to host Fifa Club World Cup in 2017 and 2018”. The National. Retrieved 29 January 2020

- ^ “UAE confirmed as hosts for FIFA Club World Cup in 2017 and 2018”. Arabian Business. Retrieved 29 January 2020

- ^ McAuley, John (18 December 2018). "Fifa Club World Cup: Al Ain beat River Plate on penalties to reach historic final". The National. Abu Dhabi. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Man United retrospectively declared 1999 world club champions by FIFA". ESPN FC. October 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "Agenda of meeting no. 10 of the FIFA Council" (PDF). FIFA. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

Appointment of hosts for the FIFA Club World Cups 2019 and 2020

[dead link] - ^ "FIFA Council appoints Qatar as host of the FIFA Club World Cup in 2019 and 2020" (Press release). Zurich: FIFA. 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ "Directivo de CONMEBOL confirma que mundial de clubes será en Japón hasta 2021". Récord. Mexico City. 24 May 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Firmino winner seals Club World Cup win". BBC. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "Bayern beat Tigres in Club World Cup final to earn sixth trophy in nine months". The Guardian. 11 February 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "Chelsea win Club World Cup: Kai Havertz winner sees off Palmeiras after extra time". BBC Sport. 12 February 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ "FIFA boss suggests 32-team Club World Cup in 2019". CBC Sports. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Associated Press. 18 November 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "FIFA considering 24-team Club World Cup to be played in summer". ESPN. Associated Press. 31 October 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "FIFA Council votes for the introduction of a revamped FIFA Club World Cup". FIFA. 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Homewood, Brian (13 April 2017). "Soccer: Qualifying for new Club World Cup would take place over four seasons". Sports News. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ Conway, Richard (23 April 2018). "Fifa set to meet over $25bn offer to launch two tournaments". BBC Sport. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ a b c Olley, James (16 December 2022). "FIFA to launch new Club World Cup format with 32 teams in 2025". ESPN. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ "Bureau of the FIFA Council decisions concerning impact of COVID-19". FIFA. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Club World Cup: Fifa to stage 32-team tournament from June 2025 – president Gianni Infantino". BBC Sport. 16 December 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Jackson, Kieran (16 December 2022). "Fifa to expand Club World Cup to 32 teams from 2025". The Independent. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ "United States to host expanded 32-team Club World Cup in 2025". ESPN. Associated Press. 23 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup 2025: Dates, format and qualifiers". FIFA. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ "FIFA accused of prioritising own interests after revealing Club World Cup plans". OneFootball. 17 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ Ames, Nick (17 December 2023). "Liverpool miss out on 2025 Club World Cup spot and potential £50m windfall". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Details of New-look Club World Cup Emerge and Not Everyone Likes It". Front Office Sports. 17 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Championship Brazil 2000". FIFA. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Pontes, Ricardo (29 May 2007). "FIFA Club World Championship 2000". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "World Club Championship axed". BBC Sport. 18 May 2001. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ "FIFA revamps Club World Championship". 20 February 2004. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Championship Toyota Cup Japan 2005". FIFA. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Nakanishi, Masanori "Komabano"; de Arruda, Marcelo Leme (30 April 2006). "FIFA Club World Championship 2005". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup Japan 2006". FIFA. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Nakanishi, Masanori "Komabano"; de Arruda, Marcelo Leme (10 May 2007). "FIFA Club World Championship 2006". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup Japan 2007". FIFA. Archived from the original on 11 March 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ de Arruda, Marcelo Leme (28 May 2008). "FIFA Club World Championship 2007". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup Japan 2008". FIFA. Archived from the original on 24 May 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Nakanishi, Masanori "Komabano"; de Arruda, Marcelo Leme (21 May 2009). "FIFA Club World Championship 2008". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup UAE 2009". FIFA. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ de Arruda, Marcelo Leme (14 May 2010). "FIFA Club World Championship 2009". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Club Estudiantes de La Plata – FC Barcelona". FIFA. 19 December 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup UAE 2010". FIFA. Archived from the original on 4 July 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ de Arruda, Marcelo Leme (17 July 2012). "FIFA Club World Championship 2010". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup Japan 2011". FIFA. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ de Arruda, Marcelo Leme (17 July 2012). "FIFA Club World Championship 2011". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Al-Sadd take third on penalties". FIFA. 18 December 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup Japan 2012". FIFA. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ de Arruda, Marcelo Leme (10 January 2013). "FIFA Club World Championship 2012". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup Morocco 2013". FIFA. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ de Arruda, Marcelo Leme (23 December 2013). "FIFA Club World Championship 2013". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup Morocco 2014". FIFA. Archived from the original on 8 August 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ de Arruda, Marcelo Leme (23 December 2014). "FIFA Club World Championship 2014". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "Auckland City claim historic bronze". FIFA. 20 December 2014. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup Japan 2015". FIFA. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ King, Ian; Stokkermans, Karel (20 December 2015). "FIFA Club World Cup 2015". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup Japan 2016". FIFA. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ Stokkermans, Karel (18 December 2016). "FIFA Club World Cup 2016". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ "Club América – Atlético Nacional". FIFA. 18 December 2016. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ "Real Madrid – Kashima Antlers". FIFA. 18 December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ King, Ian (22 December 2018). "FIFA Club World Cup 2017". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ King, Ian (3 January 2019). "FIFA Club World Cup 2018". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ Poole, Harry (21 December 2019). "Flamengo 0–1 Liverpool: Roberto Firmino's extra-time strike delivers first Club World Cup". BBC Sport. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Begley, Emlyn (11 February 2021). "Fifa Club World Cup final: Bayern Munich beat Tigres to become world champions". BBC Sport. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ "Chelsea win Club World Cup: Kai Havertz winner sees off Palmeiras after extra time". BBC Sport. 12 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ "Real Madrid 5–3 Al-Hilal: Vinicius & Federico Valverde score in Club World Cup final win". BBC Sport. 11 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Blitz, Sam (22 December 2023). "Man City 4–0 Fluminense: Rodri injury sours Club World Cup triumph as Pep Guardiola wins 14th trophy as City boss". Sky Sports. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Al-Ahly beat Urawa Red Diamonds 4–2 to finish third in Club World Cup". Reuters. 22 December 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Regulations for the FIFA Club World Cup 2022" (PDF). FIFA. 23 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d "2012 FIFA Club World Cup – Regulations" (PDF). FIFA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ a b "New Silver Trophy for Club World Champions". FIFA. 3 January 2000. Retrieved 6 March 2013.[dead link]

- ^ a b c "FIFA awards" (PDF). FIFA. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Sawaya & Moroni". Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Championship Cup". Sawaya & Moroni. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Innovative FIFA Club World Cup Trophy unveiled ahead of new tournament in 2025". FIFA. 14 November 2024. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Regulations – FIFA Club World Cup Morocco 2013" (PDF). FIFA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FIFA awards special 'Club World Champion' badge to AC Milan". FIFA. 2 February 2008. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

At a ceremony today at the Home of FIFA in Zurich, FIFA General Secretary Jerome Valcke officially presented a badge to AC Milan's CEO Adriano Galliani to honour their club's victory at the 2007 FIFA Club World Cup. This new badge will also be provided to the winning club of all future editions of the competition.

- ^ "Bayern join elite group of badge-winners". FIFA. 17 December 2012. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Corinthians join elite group of badge-wearers". FIFA. 17 December 2012. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "28 Million Dollars in Prize Money on Offer". FIFA. 3 January 2000. Retrieved 6 March 2013.[dead link]

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup: Statistical Kit" (PDF). FIFA. 5 December 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Organising committee approves tournament format with reintroduction of match for fifth place". FIFA. 12 March 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2008.

- ^ "TOYOTA END CLUB WORLD CUP SPONSORSHIP". footballchannel.asia. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ "Alibaba E-Auto signs as Presenting Partner of the FIFA Club World Cup". FIFA. 9 December 2015. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015.

- ^ Charlton, Bobby (28 December 1999). "Um desafio fascinante" [A fascinating challenge]. Jornal do Brasil (in Portuguese). p. 54. Retrieved 6 March 2013.[failed verification]

- ^ Summerscales, Robert (11 February 2023). "Real Madrid Crowned FIFA Club World Cup Champions Again As Toni Kroos Makes History". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "Club World Cup – All-time Topscorers". WorldFootball.net. 11 February 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ "Club World Cup – All-time appearances". WorldFootball.net. 11 February 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Club World Cup – All-time league table". WorldFootball.net. 11 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "Bebe Rexha to Illuminate FIFA Club World Cup Saudi Arabia 2023™ with Official Song – "It's On"". FIFA. 9 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Staunton, Peter (12 December 2014). "Why does the Club World Cup still struggle for relevance?". Goal. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ Vickery, Tim (13 December 2010). "World Club Cup deserves respect". BBC. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ "Ignored in Europe, Club World Cup finds adulation in S.America". Times of Oman. 14 December 2015. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Vickery, Tim (15 December 2008). "The prestige of the Club World Cup". BBC. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ Vickery, Tim (15 December 2017). "Balance that no longer exists; in today's globalised market the best players South Americans are representing the European champions teams". ESPN.

- ^ Vickery, Tim (22 December 2018). "River Plate's third-place win doesn't hide that South American football continues to lose ground". ESPN. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ "Club World Cup: Liverpool boss Jurgen Klopp is 'wrong person' to address Qatar issues". BBC. 17 December 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Caballero, Miguel (11 December 2015). "Mundial de Clubes, ¿la antítesis de un Mundial de Selecciones?" (in Spanish). Goal. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Masnou, Albert (18 December 2015). "El ridículo premio por ganar el Mundial de clubes". Sport (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Jones, Rory (27 January 2023). "Saran secures Fifa Club World Cup broadcast rights in 16 countries". SportsPro. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Casimiro anuncia que vai transmitir Mundial de Clubes; veja detalhes". uol. 13 January 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Fifa Club World Cup returns to Globo in Brazil". SportBusiness. 2 February 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Sim, Josh (25 January 2023). "Club World Cup broadcast rights nabbed by Canal+ and Sky Italia". SportsPro. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ Bickerton, Jake (1 February 2023). "LiveScore picks up free-to-air FIFA Club World Cup rights in Ireland". Broadcast. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ "FOX Sports Presents FIFA Club World Cup Morocco 2022™ Broadcast Schedule". Fox Sports. 30 January 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

Further reading

- Augustyn, Adam (2011). The Britannica Guide to Soccer. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-61530-581-0.

- Darby, Paul (2002). Africa, Football and Fifa: Politics, Colonialism and Resistance (Sport in the Global Society). Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 0-7146-8029-X.

- Dunmore, Tom (2011). Historical Dictionary of Soccer. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7188-5.

- Fortin, François (2003). Sports: The Complete Visual Reference. Firefly Books. ISBN 1-55297-807-9.

- Goldblatt, David (2008). The Ball Is Round: A Global History of Soccer. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-59448-296-0.

- Jozsa, Frank (2009). Global Sports: Cultures, Markets and Organizations. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-283-569-7.