Muhammad in Islam

Rasul Allah Muhammad | |

|---|---|

مُحَمَّد | |

| |

| Prophet of Islam | |

| Title | Khatam al-Nabiyyin ('Seal of the Prophets') |

| Personal | |

| Born | c. 570 CE[1] |

| Died | Monday, 12 Rabi' al-Awwal 11 AH (8 June 632 CE) |

| Resting place | Green Dome, Prophet's Mosque, Medina |

| Religion | Islam |

| Spouse | See Muhammad's wives |

| Children | See Muhammad's children |

| Parents |

|

| Notable work(s) | Constitution of Medina |

| Other names | See Names and titles of Muhammad |

| Relatives | See Family tree of Muhammad, Ahl al-Bayt ("Family of the House") |

| Arabic name | |

| Personal (Ism) | Muḥammad مُحَمَّد |

| Patronymic (Nasab) | Ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib ibn Hāshim ibn ʿAbd Manāf ibn Quṣayy ibn Kilāb ٱبْن عَبْد ٱللَّٰه بْن عَبْد ٱلْمُطَّلِب بْن هَاشِم بْن عَبْد مَنَاف بْن قُصَيّ بْن كِلَاب |

| Teknonymic (Kunya) | Abū al-Qāsim أَبُو ٱلْقَاسِم |

| Epithet (Laqab) | Khātam al-Nabiyyīn ('Seal of the Prophets') خَاتَم ٱلنَّبِيِّين |

| Muslim leader | |

| Successor | See Succession to Muhammad |

Part of a series on Islam Islamic prophets |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

In Islam, Muḥammad (Arabic: مُحَمَّد) is venerated as the Seal of the Prophets and earthly manifestation of primordial divine light (Nūr), who transmitted the eternal word of God (Qur'ān) from the angel Gabriel (Jabrāʾīl) to humans and jinn.[2] Muslims believe that the Quran, the central religious text of Islam, was revealed to Muhammad by God, and that Muhammad was sent to guide people to Islam, which is believed not to be a separate religion, but the unaltered original faith of mankind (fiṭrah), and believed to have been shared by previous prophets including Adam, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus.[3][4][5][6] The religious, social, and political tenets that Muhammad established with the Quran became the foundation of Islam and the Muslim world.[7]

According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad received his first revelation at age 40 in a cave called Hira in Mecca,[8] whereupon he started to preach the oneness of God in order to stamp out idolatry of pre-Islamic Arabia.[9][10] This led to opposition by the Meccans, with Abu Lahab and Abu Jahl as the most famous enemies of Muhammad in Islamic tradition. This led to persecution of Muhammad and his Muslim followers who fled to Medina, an event known as the Hijrah,[11][12] until Muhammad returned to fight the idolaters of Mecca, culminating in the semi-legendary Battle of Badr, conceived in Islamic tradition not only to be a battle between the Muslims and pre-Islamic polytheists, but also between the angels on Muhammad's side against the jinn and false deities siding with the Meccans. After victory, Muhammad is believed to have cleansed Arabia from polytheism and advised his followers to renounce idolatry for the sake of the unity of God.

As manifestation of God's guidance and example of renouncing idolatry, Muhammad is understood as an exemplary role-model in regards of virtue, spirituality, and moral excellence.[13] His spirituality is considered to be expressed by his journey through the seven heavens (Mi'raj). His behaviour and advice became known as the Sunnah, which forms the practical application of Muhammad's teachings. Even after his (earthly) death, Muhammad is believed to continue to exist in his primordial form and thus Muslims are expected to be able to form a personal bond with the prophet. Furthermore, Muhammad is venerated by several titles and names. As an act of respect and a form of greetings, Muslims follow the name of Muhammad by the Arabic benediction "sallallahu 'alayhi wa sallam", ("Peace be upon him"),[14] sometimes abbreviated as "SAW" or "PBUH". Muslims often refer to Muhammad as "Prophet Muhammad", or just "The Prophet" or "The Messenger", and regard him as the greatest of all Prophets.[3][15][16][17]

In the Quran

Muhammad is mentioned by name four times in the Quran.[18] The Quran reveals little about Muhammad's early life or other biographic details, but it talks about his prophetic mission, his moral excellence, and theological issues regarding Muhammad. According to the Quran, Muhammad is the last in a chain of prophets sent by God (33:40). Throughout the Quran, Muhammad is referred to as "Messenger", "Messenger of God", and "Prophet". Other terms are used, including "Warner", "bearer of glad tidings", and the "one who invites people to a Single God" (Q 12:108, and 33:45-46). The Quran asserts that Muhammad was a man who possessed the highest moral excellence, and that God made him a good example or a "goodly model" for Muslims to follow (Q 68:4, and 33:21). In several verses, the Quran explains Muhammad's relation to humanity. According to the Quran, God sent Muhammad with truth (God's message to humanity), and as a blessing to the whole world (Q 39:33, and 21:107).

According to Islamic tradition, Surah 96:1 refers to the command of the angel to Muhammad to recite the Quran.[19] Surah 17:1 is believed to be a reference to Muhammad's journey, which tradition elaborates extensively upon, meeting angels and previous prophets in heaven.[19] Surah 9:40 is seen as a reference to Muhammad and a companion (whom Sunni scholars identify with Abu Bakr) hiding from their Meccan persecutors in a cave.[20] Surah 61:6 is believed to remind the audience of the foretelling of Muhammad by Jesus.[19] This verse was also used by early Arab Muslims to claim legitimacy for their new faith in the existing religious traditions.[21]

Names and titles of praise

Muhammad is often referenced with these titles of praise or epithet:

- an-Nabi, 'the Prophet'

- ar-Rasul, 'the Messenger'

- al-Habeeb, 'the beloved'

- al-Muṣṭafa, 'the chosen one' (Quran 22:75);[22]

- al-Amin, 'the trustworthy' (Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:52:237)

- as-Sadiq, 'the honest'(Quran 33:22)

- al-Haq, 'the truthful' (Quran 10:08)

- ar-Rauf, 'the kind' (Quran 9:128)

- ‘alā khuluq ‘aẓīm (Arabic: عَلَى خُلُق عِظِيْم), 'on an exalted standard of character' (Quran 68:4)

- al-Insan al-Kamil, 'the perfect man'[23]

- Uswah Ḥasan (Arabic: أُسْوَة حَسَن), 'good example' (Quran 33:21)

- al-Khatim an-Nabiyin, 'the seal of the prophets' (Quran 33:40)

- ar-Rahmatul lil 'alameen, 'mercy of all the worlds' (Quran 21:107)

- as-Shaheed, 'the witness' (Quran 33:45)

- al-Mubashir, 'the bearer of good tidings' (Quran 11:2)

- an-Nathir, 'the warner' (Quran 11:2)

- al-Mudhakkir, 'the reminder' (Quran 88:21)

- ad-Da'i, 'the one who calls [unto God]' (Quran 12:108)

- al-Bashir, 'the announcer' (Quran 2:119)

- an-Noor, 'the light personified' (Quran 05:15)

- as-Siraj-un-Munir, 'the light-giving lamp' (Quran 33:46)

- al-Kareem, 'the noble' (Quran 69:40)

- an-Nimatullah, 'the divine favour' (Quran 16:83)

- al-Muzzammil, 'the wrapped' (Quran 73:01)

- al-Muddathir, 'the shrouded' (Quran 74:01)

- al-'Aqib, 'the last [prophet]' (Sahih Muslim, 4:1859, Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:56:732)

- al-Mutawakkil, 'the one who puts his trust [in God]' (Quran 9:129)

- al-Kutham, 'the generous one’

- al-Mahi, 'the eraser [of disbelief]' (Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:56:732)

- al-Muqaffi, 'the one who followed [all other prophets]'

- an-Nabiyyu at-Tawbah, 'the prophet of penitence’

- al-Fatih, 'the opener'

- al-Hashir, 'the gatherer (the first to be resurrected) on the day of judgement' (Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:56:732)

- as-Shafe'e, 'the intercessor' (Sahih al-Bukhari, 9:93:601, Quran 3:159, Quran 4:64, Quran 60:12)

- al-Mushaffaun, 'the one whose intercession shall be granted' (Quran 19:87, Quran 20:109).

He also has these names:

- Abu'l-Qasim, "father of Qasim";

- Ahmad, "the Praised one" (Quran 61:06);

- Hamid, "praiser";

- Mahmood, "praiseworthy";

- 'Abd-Allah, "servant of God" (Quran 25:1).

Overview

In Muslim tradition, Muhammad is depicted with otherworldly features, such as being physically illuminated. As reported by Bukhari, whenever Muhammad entered darkness, light was shining around him like moonlight.[24] Muhammad is further described as having a radiant face.[25] As such, Muhammad is believed to reflect God's names of "mercy" and "guidance", as opposed to Satan (Iblīs), who reflects "wrath" and "pride".[26][27]

Though according to tradition, Muhammad has said that he is just an ordinary human, several miracles are said to have been performed by him.[28] To the Quran statement, as a reminder of Muhammad's human nature "I am only a human being like you", Muslims responded: "True, but like a ruby among stones.", pointing at the outward resemblance of Muhammad to an ordinary human but inwardly carrying the Divine Light.[29]

In post-Quranic times, some Muslims view Muhammad merely as a warner of God's judgement and not a miracle worker.[30] According to one account of Muhammad, the Quran is the only miracle Muhammad has been bestowed with.[30]

Final prophet

Muhammad is regarded as the final messenger and prophet by all the main branches of Islam who was sent by God to guide humanity to the right way (Quran 7:157).[3][31][32][33][34] The Quran uses the designation Khatam an-Nabiyyin (Surah 33:40) (Arabic:خاتم النبين), which is translated as Seal of the Prophets. The title is generally regarded by Muslims as meaning that Muhammad is the last in the series of prophets beginning with Adam.[35][36][37] Believing Muhammad is the last prophet is a fundamental belief,[38][39] shared by both Sunni and Shi'i theology.[40][41]

Although Muhammad is considered to be the last prophet sent, he is supposed to be the first prophet to be created.[42] In Sunni Islam, it is attributed to Al-Tirmidhi, that when Muhammad was asked, when his prophethood started, he answered: "When Adam was between the spirit and the body".[43] A more popular but less authenticated version states "when Adam was between water and mud."[44] As recorded by Ibn Sa'd, Qatada ibn Di'ama quoted Muhammad: "I was the first human in creation and I am the last one on resurrection".[45]

According to a Shia tradition, not only Muhammad, but also Ali preceded the creation of Adam. Accordingly, after the angels prostrated themselves before Adam, God ordered Adam to look at the Throne of God. Then he saw the radiant body of Muhammad and his family.[46] When Adam was in heaven, he read the Shahada inscribed on the throne of God, which also mentioned Ali in Shia tradition.[46]

Muslim philosophy and rationalism

Islamic philosophy (Falsafa) attempts to offer scientific explanations for prophecies.[47] Such philosophical theories may also have been used to legitimize Muhammad as a lawgiver and a statesman.[47] Muhammad was identified by some Islamic scholars with the Platonic logos, due to the belief in his pre-existence.[48]

Integrating translations of Aristotelian philosophy into early Islamic philosophy, al-Farabi accepted the existence of various celestial intellects. Already in early Neo-Platonic commentaries on Aristotle, these intellects have been compared to light.[49] Al-Fabari depicted the passive intellect of the individual human as receiving universal concepts from the celestial active intellect.[50] Only when the individual intellect is in conjunction with the active intellect, it is able to receive the thoughts of the active intellect in its own mental capacities. A distinction is made between prophecy and revelation, the latter being passed down directly to the imaginative faculties of the individual.[51] He explained Muhammad's prophetic abilities through this epistemilogical model,[52] which was adopted and elaborated on by later Muslim scholars, such as Avicenna, al-Ghazali, and ibn Arabi.[53]

The Sufi tradition of ibn Arabi expanded upon the idea of Muhammad's pre-existence, combined with rationalistic theory. Qunawi identifies Muhammad with the pen (Qalam), which was ordered by God to write down everything what will exist and happen.[54] Despite some resemblance of the Christian doctrine of the pre-existence of Christ, Islam always depicts Muhammad as a created being and never as part or a person within God.[55]

Morality and Sunnah

Muslims believe that Muhammad was the possessor of moral virtues at the highest level, and was a man of moral excellence.[13][32] He represented the 'prototype of human perfection' and was the best among God's creations.[13][56] Consequently, to the Muslims, his life and character are an excellent example to be emulated both at social and spiritual levels.[32][56] The virtues that characterize him are modesty and humility, forgiveness and generosity, honesty, justice, patience, and self-denial.[13] Muslim biographers of Muhammad in their books have shed much light on the moral character of Muhammad. In addition, there is a genre of biography that approaches his life by focusing on his moral qualities rather than discussing the external affairs of his life.[13][32] These scholars note he maintained honesty and justice in his deeds.[57]

For more than thirteen hundred years, Muslims have modeled their lives after their prophet Muhammad. They awaken every morning as he awakened; they eat as he ate; they wash as he washed; and they behave even in the minutest acts of daily life as he behaved.

— S. A. Nigosian

In Muslim legal and religious thought, Muhammad, inspired by God to act wisely and in accordance with his will, provides an example that complements God's revelation as expressed in the Quran; and his actions and sayings – known as Sunnah – are a model for Muslim conduct.[58] The Sunnah can be defined as "the actions, decisions, and practices that Muhammad approved, allowed, or condoned".[59] It also includes Muhammad's confirmation to someone's particular action or manner (during Muhammad's lifetime) which, when communicated to Muhammad, was generally approved by him.[60] The Sunnah, as recorded in the Hadith literature, encompasses everyday activities related to men's domestic, social, economic, and political life.[59] It addresses a broad array of activities and Islamic beliefs ranging from the simple practices, like the proper way of entering a mosque and private cleanliness, to questions involving the love between God and humans.[61] The Sunnah of Muhammad serves as a model for Muslims to shape their lives in that standard. The Quran tells the believers to offer prayer, fast, perform pilgrimage, and pay Zakat, but it was Muhammad who practically taught the believers how to perform all these.[61]

Biography

Muhammad's biography is stored in Al-Sīra al-Nabawiyya (prophetic biography). One of the earliest written prophetic biographies is attributed to ibn ʾIsḥāq, which has been lost; only a more recent version edited by ibn Hishām has survived.[62] However, elements from ibn ʾIsḥāq's biography survive in other works, such as al-Ṭabarī's history of the prophets.[62] Muhammad is often described in both supernatural and worldly terms. While early biographies present him as a pre-eternal human soul with miraculous powers and sinlessness, he remains humanly imitable in his love and devotion, which would become the sunnah for his followers.[63]

Since the 19th century, Muhammad's biographies have become increasingly intertwined with non-Muslim accounts of Muhammad,[64] thus blurring the distinction between the prophetic Muhammad from Islamic tradition and the humanized Muhammad in non-Muslim depiction.[65] Accordingly, pre-modern Islamic accounts revolve around Muhammad's function as a prophet and his miraculous ascent to heaven, while many modern Islamic biographers reconstruct his life as an ideal statesman or social reformer.[66] A particular importance of Muhammad's role as a military leader began with the writings of Ahmet Refik Altınay.[67] The shortage of hagiographical accounts in the modern age led to a general acceptance of the depiction of Muhammad's history by non-Muslim scholars as well.[67]

Early years

Muhammad, the son of 'Abdullah ibn 'Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim and his wife Aminah, was born in approximately 570 CE[1][n 1] in the city of Mecca in the Arabian Peninsula. He was a member of the family of Banu Hashim, a respected branch of the prestigious and influential Quraysh tribe. It is generally said that 'Abd al-Muttalib named the child "Muhammad" (Arabic: مُحَمَّد).[68]

Birth

According to Sufis, Muhammad is not only considered as the historical figure Muhammad, but also the earthly manifestation of the cosmic Muhammad, predating the creation of the Earth or Adam.[69][70] The motifs of Barakah and Nūr are frequently invoked to describe Muhammad's birth as a miraculous event.[71] According to the Sīra of Ibn Isḥāq, a light was transferred from Muhammad's father to his mother at the time of his conception.[71][72] During pregnancy, a light radiated from the belly of Muhammad's mother.[72] Ibn Hischām's Sīra refers to a vision experienced by Muhammad's mother. An unknown being came to her announcing Muhammad:

"You have conceived the master of this community; when he falls to the earth, say "I commend him to the protection of the One from the evil of every envier" then name him Muhammad."

The tradition that Muhammad's soul pre-dates his birth has been justified by the Quranic statement that "God created the spirits before the bodies".[73] Others, such as Sahl al-Tustari, believed that the Quranic Verse of Light alludes to Muhammad's pre-existence, comparing it to the Light of Muhammad.[74][75] Some later reformative theologians, such as al-Ghazali (Asharite) and Ibn Taymiyyah (proto-Salafi) rejected that Muhammad existed before birth and that only the idea of Muhammad has existed prior to his physical conception.[76][77]

Childhood

Muhammad was orphaned when young. Some months before the birth of Muhammad, his father died near Medina on a mercantile expedition to Syria.[78][79][80] When Muhammad was six, he accompanied his mother Amina on her visit to Medina, probably to visit her late husband's tomb. While returning to Mecca, Amina died at a desolate place called Abwa, about half-way to Mecca, and was buried there. Muhammad was now taken in by his paternal grandfather Abd al-Muttalib, who himself died when Muhammad was eight, leaving him in the care of his uncle Abu Talib. In Islamic tradition, Muhammad's being orphaned at an early age has been seen as a part of divine plan to enable him to "develop early the qualities of self-reliance, reflection, and steadfastness".[81] Muslim scholar Muhammad Ali sees the tale of Muhammad as a spiritual parallel to the life of Moses, considering many aspects of their lives to be shared.[82]

According to Arab custom, after his birth, infant Muhammad was sent to Banu Sa'ad clan, a neighboring Bedouin tribe, so that he could acquire the pure speech and free manners of the desert.[83] There, Muhammad spent the first five years of his life with his foster-mother Halima. Islamic tradition holds that during this period, God sent two angels who opened his chest, took out the heart, and removed a blood-clot from it. It was then washed with Zamzam water. In Islamic tradition, this incident means that God purified his prophet and protected him from sin.[84][85]

Around the age of twelve, Muhammad accompanied his uncle Abu Talib in a mercantile journey to Syria, and gained experience in commercial enterprise.[86] On this journey Muhammad is said to have been recognized by a Christian monk, Bahira, who prophesied about Muhammad's future as a prophet of God.[10][87]

Around the age of 25, Muhammad was employed as the caretaker of the mercantile activities of Khadijah, a Qurayshi lady.

Social welfare

Between 580 CE and 590 CE, Mecca experienced a bloody feud between Quraysh and Bani Hawazin that lasted for four years, before a truce was reached. After the truce, an alliance named Hilf al-Fudul (The Pact of the Virtuous)[88] was formed to check further violence and injustice; and to stand on the side of the oppressed, an oath was taken by the descendants of Hashim and the kindred families, where Muhammad was also a member.[86]

Islamic tradition credits Muhammad with settling a dispute peacefully, regarding setting the sacred Black Stone on the wall of Kaaba, where the clan leaders could not decide on which clan should have the honor of doing that. The Black Stone was removed to facilitate the rebuilding of Kaaba because of its dilapidated condition. The disagreement grew tense, and bloodshed became likely. The clan leaders agreed to wait for the next man to come through the gate of Kaaba and ask him to choose. The 35-year-old Muhammad entered through that gate first, asked for a mantle which he spread on the ground, and placed the stone at its center. Muhammad had the clans' leaders lift a corner of it until the mantle reached the appropriate height, and then himself placed the stone on the proper place. Thus, an ensuing bloodshed was averted by the wisdom of Muhammad.[89]

Prophethood

When Muhammad was 40 years old,[90] he began to receive his first revelations in 610 CE. The first revealed verses were the first five verses of Surah al-Alaq that the archangel Gabriel (Jabrāʾīl) brought from God to Muhammad in the Cave of Hira in Mount Hira.[91][92][93]

While he was contemplating in the Cave of Hira,[94] Gabriel appeared before him and commanded him to "read", upon which Muhammad replied, as he is considered illiterate in Islamic tradition:[95] 'I am unable to read'. Thereupon the angel caught hold of him and pressed him heavily. This is said to have been repeated three times until Muhammad recited the revealed part of the Quran.[96] This happened two more times after which the angel commanded Muhammad to recite the following verses:[91][92]

Read, ˹O Prophet,˺ in the Name of your Lord Who created—

created humans from a clinging clot.

Read! And your Lord is the Most Generous,

Who taught by the pen—

taught humanity what they knew not.

These revelations are believed to have entered Muhammad's heart (Qalb) in form of visions and sounds, which he then transcripted into words, known as the verbatim of God.[97][98][99] These were later written down and collected and came to be known as Quran, the central religious text of Islam.[100][101][102][103]

During the first three years of his ministry, Muhammad preached Islam privately, mainly among his near relatives and close acquaintances. The first to believe him was his wife Khadijah, who was followed by Ali, his cousin, and Zayd ibn Harithah. Among the early converts were Abu Bakr, Uthman ibn Affan, Hamza ibn Abdul Muttalib, Sa'ad ibn Abi Waqqas, Abdullah ibn Masud, Arqam, Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, Ammar ibn Yasir and Bilal ibn Rabah.[104]

Opposition and persecution

Muhammad's early teachings invited vehement opposition from the wealthy and leading clans of Mecca who feared the loss not only of their ancestral paganism but also of the lucrative pilgrimage business.[105] At first, the opposition was confined to ridicule and sarcasm which proved insufficient to arrest Muhammad's faith from flourishing, and soon they resorted to active persecution.[106] These included verbal attack, ostracism, unsuccessful boycott, and physical persecution.[105][107] Alarmed by mounting persecution on the newly converts, Muhammad in 615 CE directed some of his followers to migrate to neighboring Abyssinia (present day Ethiopia), a land ruled by king Aṣḥama ibn Abjar, famous for his justice and intelligence.[108] Accordingly, eleven men and four women made their flight, and were followed by more in later time.[108][109]

Back in Mecca, Muhammad was gaining new followers, including figures like Umar ibn Al-Khattāb. Muhammad's position was greatly strengthened by their acceptance of Islam, and the Quraysh became much perturbed. Upset by the fear of losing the leading position, the merchants and clan-leaders tried to come to an agreement with Muhammad. They offered Muhammad the prospect of higher social status and advantageous marriage proposal in exchange for forsaking his preaching. Muhammad rejected both offers, asserting his nomination as a messenger by God.[110][111]

Last years in Mecca

The death of his uncle Abu Talib left Muhammad unprotected, and exposed him to some mischief of Quraysh, which he endured with great steadfastness. An uncle and a bitter enemy of Muhammad, Abu Lahab succeeded Abu Talib as clan chief, and soon withdrew the clan's protection from Muhammad.[112] Around this time, Muhammad visited Ta'if, a city some sixty kilometers east of Mecca, to preach Islam, but met with severe hostility from its inhabitants who pelted him with stones causing bleeding. It is said that God sent angels of the mountain to Muhammad who asked Muhammad's permission to crush the people of Ta'if in between the mountains, but Muhammad said 'No'.[113][114] At the pilgrimage season of 620, Muhammad met six men of Khazraj tribe from Yathrib (later named Medina), propounded to them the doctrines of Islam, and recited portions of Quran.[112][115] Impressed by this, the six embraced Islam,[10] and at the Pilgrimage of 621, five of them brought seven others with them. These twelve informed Muhammad of the beginning of gradual development of Islam in Medina, and took a formal pledge of allegiance at Muhammad's hand, promising to accept him as a prophet, to worship none but one God, and to renounce certain sins like theft, adultery, murder and the like. This is known as the "First Pledge of al-Aqaba".[116][117] At their request, Muhammad sent with them Mus‘ab ibn 'Umair, who is said to successfully convince his audience to embrace Islam according to Muslim biographies.[118]

The next year, at the pilgrimage of June 622, a delegation of around 75 converted Muslims of Aws and Khazraj tribes from Yathrib came. They invited him to come to Medina as an arbitrator to reconcile the hostile tribes.[11] This is known as the "Second Pledge of al-'Aqabah",[116][119] and was a 'politico-religious' success that paved the way for his and his followers' emigration to Medina.[120] Following the pledges, Muhammad ordered his followers to migrate to Yathrib in small groups, and within a short period, most of the Muslims of Mecca migrated there.[121]

Emigration to Medina

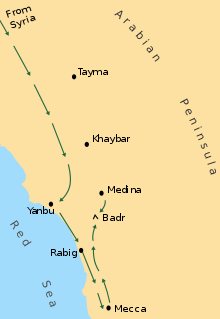

Because of assassination attempts from the Quraysh, and prospect of success in Yathrib, a city 320 km (200 mi) north of Mecca, Muhammad emigrated there in 622.[122] According to Muslim tradition, after receiving divine direction to depart Mecca, Muhammad began taking preparation and informed Abu Bakr of his plan. On the night of his departure, Muhammad's house was besieged by men of the Quraysh who planned to kill him in the morning. At the time, Muhammad possessed various properties of the Quraysh given to him in trust; so he handed them over to 'Ali and directed him to return them to their owners. It is said that when Muhammad emerged from his house, he recited the ninth verse of surah Ya-Sin of the Quran and threw a handful of dust at the direction of the besiegers, rendering the besiegers unable to see him.[123] After eight days' journey, Muhammad entered the outskirts of Medina on 28 June 622,[124] but did not enter the city directly. He stopped at a place called Quba some miles from the main city, and established a mosque there. On 2 July 622, he entered the city.[124] Yathrib was soon renamed Madinat an-Nabi (Arabic: مَدينةالنّبي 'City of the Prophet'), but an-Nabi was soon dropped, so its name is "Medina", meaning 'the city'.[125]

In Medina

In Medina, Muhammad's first focus was on the construction of a mosque, which, when completed, was of an austere nature.[126] Apart from being the center of prayer service, the mosque also served as a headquarters of administrative activities. Adjacent to the mosque was built the quarters for Muhammad's family. As there was no definite arrangement for calling people to prayer, Bilal ibn Ribah was appointed to call people in a loud voice at each prayer time, a system later replaced by Adhan believed to be informed to Abdullah ibn Zayd in his dream, and liked and introduced by Muhammad.

In order to establish peaceful coexistence among this heterogeneous population, Muhammad invited the leading personalities of all the communities to reach a formal agreement which would provide a harmony among the communities and security to the city of Medina, and finally drew up the Constitution of Medina, also known as the Medina Charter, which formed "a kind of alliance or federation" among the prevailing communities.[122] It specified the mutual rights and obligations of the Muslims and Jews of Medina, and prohibited any alliance with the outside enemies. It also declared that any dispute would be referred to Muhammad for settlement.[127]

Battles

Battle of Badr

In the year 622, Muhammad and around 100 followers fled from Mecca to Medina, due to violent persecution. It is here, when Muslims are for the first time permitted by the Quran to fight against their pagan Meccan adversaries:

"Permission [to fight] is given to those who are attacked, because they are oppressed and verily God is powerful in His support; those who have been expelled from their homes without right, only because they say our Lord is God (Allah)."(22:39-40)[128]

These ghazi raids escalated into a war in 624 between Muslims and Meccan pagans, known as the Battle of Badr.[129] This is also considered to be the first time Muhammad used a weapon.[130] The battle is described with supernatural images. In Islamic tradition, the battle is not only between the human Muslims and the human pagans, but also between the angels on the behalf of the Muslims and the pagan deities (jinn) siding with their worshippers.[129] The Muslims receiving heavenly support is also alluded in the Quran (8:9).[131]

Before the battle, Iblis (Satan) appeared to the pagan Meccans in form of a man called Suraqa and incites them, including Abu Lahab[132][133] and Abu Jahl,[134] to wage war against Muhammad, promising them to support them.[135] In Shia sources, the visitor is explicitly called Shaiṭān (the Devil).[135] However, Iblis ultimately abandons the pagan Meccans before the fight begins when he recognizes that God and the angels are fighting on Muhammad's side,[135] alluded in the Quran by stating that the devil proclaims that he "fears God" ('akhafu 'llah), which can mean both, that he is reverencing or frightened about God (the latter one the preferred translation).[136] Islamic tradition holds that, as reported in Suyuti's al-Ḥabā’ik fī akhbār almalā’ik, angels were never killed except during the Battle of Badr.[137]

The intervention of the angels at the battle and the victory of the Muslims despite being outnumbered against the pagan Meccans is often considered a miraculous event in Muslim tradition.[138] After the battle, Muhammad receives the Sword Zulfiqar from the archangel Gabriel.[130]

Treason, attacks, and siege

The Quraysh soon led an army of 3,000 men and fought the Muslim force, consisting of 700 men, in the Battle of Uhud. The predicament of Muslims at this battle has been seen by Islamic scholars as a result of disobedience of the command of Muhammad: Muslims realized that they could not succeed unless guided by him.[139]

After the Battle of Uhud, Tulayha ibn Khuwaylid, chief of Banu Asad, and Sufyan ibn Khalid, chief of Banu Lahyan, tried to march against Medina but were rendered unsuccessful. Ten Muslims, recruited by some local tribes to learn the tenets of Islam, were treacherously murdered: eight of them being killed at a place called Raji, and the remaining two being taken to Mecca as captives and killed by Quraysh.[10][140] About the same time, a group of seventy Muslims, sent to propagate Islam to the people of Nejd, was put to a massacre by Amir ibn al-Tufayl's Banu Amir and other tribes. Only two of them escaped, returned to Medina, and informed Muhammad of the incidents.

Around 5 AH (627 CE), a large combined force of at least 10,000 men from Quraysh, Ghatafan, Banu Asad, and other pagan tribes known as the confederacy was formed to attack the Muslims mainly at the instigation and efforts of Jewish leader Huyayy ibn Akhtab and it marched towards Medina. The trench dug by the Muslims and the adverse weather foiled their siege of Medina, and the confederacy left with heavy losses. The Quran says that God dispersed the disbelievers and thwarted their plans (33:5). The Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza, who were allied with Muhammad before the Battle of the Trench, were charged with treason and besieged by the Muslims commanded by Muhammad.[141] After Banu Qurayza agreed to accept whatever decision Sa'ad ibn Mua'dh would take about them, Sa'ad pronounced that the male members be executed and the women and children be considered as war captives.[142][143]

Around 6 AH (628 CE) the nascent Islamic state was somewhat consolidated when Muhammad left Medina to perform pilgrimage at Mecca, but was intercepted en route by the Quraysh who ended up in a treaty with the Muslims known as the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah.[144]

Diplomacy

Around the end of 6 AH and the beginning of 7 AH (628 CE), Muhammad sent letters to various heads of state asking them to accept Islam and to worship only one God.[145] Among them were Heraclius, the emperor of Byzantium; Khosrau II, the emperor of Persia; the Negus of Ethiopia; Muqawqis, the ruler of Egypt; Harith Gassani, the governor of Syria; and Munzir ibn Sawa, the ruler of Bahrain. In 6 AH, Khalid ibn al-Walid accepted Islam who later was to play a decisive role in the expansion of Islamic empire. In 7 AH, the Jewish leaders of Khaybar – a place some 200 miles from Medina – started instigating the Jewish and Ghatafan tribes against Medina.[10][146] When negotiation failed, Muhammad ordered the blockade of the Khaybar forts, and its inhabitants surrendered after some days. The lands of Khaybar came under Muslim control. Muhammad however granted the Jewish request to retain the lands under their control.[10] In 629 CE (7 AH), in accordance with the terms of the Hudaybiyyah treaty, Muhammad and the Muslims performed their lesser pilgrimage (Umrah) to Mecca and left the city after three days.[147]

Conquest of Mecca

In 629 CE, the Banu Bakr tribe, an ally of Quraysh, attacked the Muslims' ally tribe Banu Khuza'a, and killed several of them.[148] The Quraysh openly helped Banu Bakr in their attack, which in return, violated the terms of the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah. Of the three options now advanced by Muhammad, they decided to cancel the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah.[149] Muhammad started taking preparation for Mecca campaign. On 29 November 629 (6th of Ramadan, 8 AH),[150] Muhammad set out with 10,000 companions, and stopped at a nearby place from Mecca called Marr-uz-Zahran. When Meccan leader Abu Sufyan came to gather intelligence, he was detected and arrested by the guards. Umar ibn al-Khattab wanted the execution of Abu Sufyan for his past offenses, but Muhammad spared his life after he converted to Islam. On 11 December 629 (18th of Ramadan, 8 AH), he entered Mecca almost unresisted, and declared a general amnesty for all those who had committed offences against Islam and himself.

After the Mecca conquest and the victory at the Battle of Hunayn, the supremacy of the Muslims was somewhat established throughout the Arabian peninsula.[151] Various tribes started to send their representatives to express their loyalty to Muhammad. In the year 9 AH (630 CE), Zakat—which is the obligatory charity in Islam—was introduced and was accepted by most of the people. A few tribes initially refused to pay it, but gradually accepted.

In October 630 CE, upon receiving news that the Byzantine was gathering a large army at the Syrian area to attack Medina, and because of reports of hostility adopted against Muslims,[152] Muhammad arranged his Muslim army, and came out to face them. On the way, they reached a place called Hijr where remnants of the ruined Thamud nation were scattered. Muhammad warned them of the sandstorm typical to the place, and forbade them not to use the well waters there.[10] By the time they reached Tabuk, they got the news of Byzantine's retreat, or according to some sources, they came to know that the news of Byzantine gathering was wrong.[153] Muhammad signed treaties with the bordering tribes who agreed to pay tribute in exchange of getting security. It is said that as these tribes were at the border area between Syria (then under Byzantine control) and Arabia (then under Muslim control), signing treaties with them ensured the security of the whole area. Some months after the return from Tabuk, Muhammad's infant son Ibrahim died which eventually coincided with a sun eclipse. When people said that the eclipse had occurred to mourn Ibrahim's death, Muhammad said: "the sun and the moon are from among the signs of God. The eclipses occur neither for the death nor for the birth of any man".[154] After the Tabuk expedition, the Banu Thaqif tribe of Taif sent their representative team to Muhammad to inform their intention of accepting Islam on condition that they be allowed to retain their Lat idol with them and that they be exempted from prayers. Given that these conditions were inconsistent with Islamic principles, Muhammad rejected their demands and said "There is no good in a religion in which prayer is ruled out".[155][156] After Banu Thaqif tribe of Taif accepted Islam, many other tribes of Hejaz followed them and declared their allegiance to Islam.[157]

Final days

Farewell Pilgrimage

In 631 CE, during the Hajj season, Muhammad appointed Abu Bakr to lead 300 Muslims to the pilgrimage in Mecca. As per old custom, many pagans from other parts of Arabia came to Mecca to perform pilgrimage in pre-Islamic manner. Ali, at the direction of Muhammad, delivered a sermon stipulating the new rites of Hajj and abrogating the pagan rites. He especially declared that no unbeliever, pagan, and naked man would be allowed to circumambulate the Kaaba from the next year. After this declaration was made, a vast number of people of Bahrain, Yemen, and Yamama, who included both the pagans and the People of the Book, gradually embraced Islam. Next year, in 632 CE, Muhammad performed hajj and taught Muslims first-hand the various rites of Hajj.[32] On the 9th of Dhu al-Hijjah, from Mount Arafat, he delivered his Farewell Sermon in which he abolished old blood feuds and disputes based on the former tribal system, repudiated racial discrimination, and advised people to "be good to women". According to Sunni tafsir, the following Quranic verse was delivered during this event: "Today I have perfected your religion, and completed my favours for you and chosen Islam as a religion for you" (Q 5:3).[158]

Death

It is narrated in Sahih al-Bukhari that at the time of death, Muhammad was dipping his hands in water and was wiping his face with them saying "There is no god but God; indeed death has its pangs."[159] He died on June 8, 632, in Medina, at the age of 62 or 63, in the house of his wife Aisha.[160][161] The Sīra states that Muhammad, like all the other prophets, was given the choice to live or to die.[64] At the time of Muhammad's death, a visitor (identified with Azrael) approached him, whereupon he asked him to come back in an hour, so he has time to take leave from his wives and daughters.[162]

For many Muslims of the Medieval period (and many today), Muhammad is not imagined to be inactive after his death. Though not elaborating in detail on Muhammad's whereabouts until Judgement Day, early hadiths indicate that Muhammad was considered to have a continued existence and accessibility.[163] At least in the 11th century, it is attested that Muslims consider Muhammad to be still alive.[163] Abu Mansur al-Baghdadi writes that Muhammad came back to life after his death and continues to participate in his community, takes pleasure in their good deeds and is saddened by their sins.[163] Many blessings and greetings incorporated in daily phrases and rituals, such as the five obligatory prayers, reinforce the individuals' personal connection with Muhammad.[164]

Veneration

Muhammad is highly venerated by the Muslims,[165] and is sometimes considered by them to be the greatest of all the prophets.[3][15][16]

In speaking, Muslims attach the title "Prophet" to Muhammad's name, and always follow it with the greeting sallallahu 'alayhi wa sallam (صَلّى الله عليه وسلّم, "Peace be upon him"),[14] sometimes in written form abbreviated ﷺ.

Muslims do not worship Muhammad as worship in Islam is only for God.[16][166][167]

Qindīl

Over the year of the Islamic calendar, Muslims observe, with an exception to the Wahhabis,[168] five holidays dedicated to important events in Muhammad's life.[169] At these days, Muslims celebrate by meeting to read from the Quran, tell stories about Muhammad, and offer free food.[169]

On Mevlid Qindīl Muslims celebrate the birthday of Muhammad as his arrival from primeval times on earth.[69] The practise reaches back to the early stages of Islam, but was declared an official holiday by the Ottomans in 1588.[170]

Laylat al-Raghaib marks the beginning of the three holy months (Rajab, Sha'ban and leading to Ramadan) in the Islamic calendar.[171] According to Islamic legends, at the night of reghaib, the angels gather around the Kaaba and request forgiveness from God for those who fast on Raghaib.[172]

At Miʿrāj-Qindīl (also spelled as Meraj-ul-Alam), Muslims commemorate Muhammad's ascension to heaven on the 27th of Rajab. Niṣf šaʿbān is observed at the 15th of Sha'ban. Laylat al-Qadr (also known as Kadir Gecesi) is observed at the end of Ramadan/Ramazan, and considered to be the Night when Muhammad received his first revelation.[173]

Sakal-ı Şerif

Sakal-ı Şerif refers to hair believed to be from the beard or hair of Prophet Muhammad. They are usually kept in museums, mosques, and homes, across Muslim countries.[174][175]

According to Muslim beliefs, the companions (ṣaḥāba) of Muhammad took some of Prophet's hair before it fell to the ground when he shaved his beard and kept it, as it is believed to emanate Barakah.[175][176]

Intercession

Muslims see Muhammad as primary intercessor and believe that he will intercede on behalf of the believers on Last Judgment day.[177] This non-Qur'anic vision of Muhammad's eschatological role appears for the first time in the inscriptions of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, completed in 72 AH (691–692 CE).[178] Sunni hadith collections emphasize Muhammad's role of interceding for his community or even humanity at large on Judgement Day.[179]

Muhammad's tomb in Medina is considered a holy place for Muslims and is visited by most pilgrims who go to Mecca for Hajj.[180][181] Since it is mentioned in a hadith of Muhammad, it is believed that his grave provides the visitor with blessings:[182]

"He who visits my grave will be entitled to my intercession" and in a different version "I will intercede for those who have visited me or my tomb."[183][184][185]

Based on a hadith by Tirmidhi, ibn Arabi explains in al-Futuhat that Muhammad intercedes first for the angels, then for (other) prophets, then for the saints, then the believers, animals, plants, and inanimate objects last.[186]

Night Journey and Ascension

The ’Isrā’ wal-Miʿrāj refers to Muhammad's "Night Journey" and "Ascension through the seven heavens" in Islamic tradition. Many sources consider these two events to have happened in the same night. There is a disagreement if this refers to physical or spiritual events, or both.[187] While the Quran only refers briefly to this event in Surah 17 Al-Isra,[188] later sources, including the ḥadīth corpus,[189] expand on this event.

Later Sunni tradition generally agrees that Muhammad's Ascension was physical. Ash'arite scholar al-Taftāzāni (1322–1390) writes "it is established by so well-known a tradition that he who denies it is an innovator (mubtādi)." and rejects the idea of a purely spiritual ascension as an idea of the philosophers (muʿtazilī).[190]

In modern age, Muhammad's Ascension is celebrated as Miʿrāj Qindīl throughout the Muslim world.[191][192]

Ibn Abbas' oral versions

In the first two centuries of the Islamic calendar, the vast majority of fragments of Muhammad's Night Journeys have been transmitted orally.[194] It is only in the eight and ninth centuries CE that oral tradition began to be written down. Many elements of the story are attributed to ibn ʿAbbās, respected by both Sunni and Shia scholars.[195] The ibn ʿAbbās version was popular right up until the middle periods of Islamic history, and transmitted to the royal courts from Castille in al-Andalus, Zabid in Yemen, and Tabriz in Persia. The ibn ʿAbbās versions are not to be understood as a unified narrative, but a corpus of variant texts with common aspects, often featuring otherworldly elements.[193] Later versions vary in other details regarding both the Ascension as well as the Night Journey, often omitting supernatural events. One hypothesis is that the ibn ʿAbbās narrative was suspected to be Shia propaganda at some point in early Islam, however, this is merely conjectural[196] and does not diminish its popularity later onwards in both Sunni and Shia circles.

Ibn ʾIsḥāq's writings

The earliest compounded account on the Miʿrāj is found in the famous biography of Muhammad written by ibn ʾIsḥāq's Biography of the Prophet (Sīrah).[196][197] While this narrative is rather fragmentary and a summary, later Muslim authorities, provide further details around this basic outline.[197] The story is mostly known only through the recension of ibn Hishām, until the discovery of ibn ʾIsḥāq's recension by Yunus ibn Bukayr.[196] Both versions are preceded by a reference to Surah 27:7, the question why God did not send an angel to accompany Muhammad, suggesting that the author holds the Night Journey to be a response to Muhammad's opponents.[198] Both sources agree that by the time the Journey happened, "Islam had already spread in Mecca and all their tribes."[198] Another anecdote they have in common is a reference to a report to Aisha, that the Night Journey only happened in spirit (rūḥ), but Muhammad's body would have never left. Although these recensions support that Muhammad travelled only spiritually, the later Sunni scholarly consensus is that Muhammad was lifted up physically, indicating a disagreement on the nature of Muhammad's Night Journey in the first century of the Muslim community.[198]

According to ibn Hishām's recension, Muhammad slept next to the Kaaba, when he was woken up by the archangel (muqarrab) Gabriel (Jibrāʾīl). Then he was guided to the sacred enclosure, where he met the mystical animal Buraq. Mounting this creature, he is carried, accompanied by Gabriel, to Jerusalem, where he met the Prophets Abraham, Moses, and Jesus, whereupon leading them in prayer. Ibn ʾIsḥāq's account on Muhammad's journey ends here. However, when Muhammad returned to Mecca, he is quoted as saying:

"after the completion of my business in Jerusalem a ladder was brought to me finer than any I have ever seen. It is to this the dying man looks when carried to the place."[197]

The narrative further states that Muhammad climbed up the ladder through the heavens until he reaches God's presence, where he receives the five-daily prayers.[197] Each heaven is guarded by an angel at the gate. It is only by Gabriel's permission he can enter.[197] In the different heavens, he further meets preceding prophets, including Abraham, Joseph, Moses, John the Baptist, and Jesus.[189] During this Night Journey, God instructed Muhammad to the five-time daily prayers (Ṣalāh) for the believers.[199][189]

Ibn Bukayr's account revolves much more around Muhammad's stay in Jerusalem and performing the prayers with the other prophets. The ascension to the heavens is almost entirely neglected.[200] However, the text quickly refers to Muhammad visiting hell, heaven, receiving the obligatory prayers, and choosing from different cups of liquid, indicating that the author was aware of more extensive material regarding the Night Journey, but chose to omit them.[200] The absence of extensive details about Muhammad's travel through the heavens, while receiving the five obligatory prayers in Jerusalem instead, might be an indication that these two stories were originally thought to be separate events, but unified into one Night Journey by ibn ʾIsḥāq.[200]

Ibn Sa'd's Ascension and Night Journey stories

Ibn Sa'd, a contemporary of ibn Hishām, narrates these two Journeys as separate events, even assigning them to two different dates.[202] He understands the Ascension (Miʿrāj) to precede the Night Journey to Jerusalem (’Isrā’).[203] According to ibn Sa'd's account, Muhammad was woken up by the pair of angels Gabriel and Michael (Mīkhāʾīl), telling him to "come away for what you asked of God", preceded by the quote "the Prophet used to ask his Lord to show him paradise and hellfire."[203] This version lacks elements added in other versions unifying the Ascension with the Night Journey, such as meeting the angels and the prophets in the heavens, no opening of Muhammad's chest mentioned in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, and no dialogue with God or that the obligatory prayers might have originally been fifty.[204]

According to ibn Sa'd, the Night Journey (to Jerusalem) happens six months later.[203] Like in the accounts of ibn Hishām's and ibn Bukayr, and unlike the al-Kutub al-Sitta, ibn Sa'd offers the names of those anecdotes he uses.[204] Many of them are associated with the Ahl al-Bayt, who confirm that Muhammad has gone missing, and they went out to look after him, indicating that the Night Journey to Jerusalem was a physical one.[205] Given that there is no mention of Aisha's account that the Journey was spiritual journey, despite claiming to include her in his sources, suggested that the debate of the corporeality of Muhammad's journey, might have a political undertone, a disagreement between Sunni and Shia sources.[205]

Splitting of the Moon

Surah 54:1-2 refers in Islamic tradition to Muhammad splitting the Moon in view of the Quraysh.[206][207] Historically speaking, the event probably refers to a lunar eclipse as they happened between 610 and 622 in Mecca and was considered a sign of God, linked to an apocalyptic event.[208]

Those who down-played the miraculous works of Muhammad regarded the event as a form of lunar eclipse. Abd al-Razzaq al-San'ani said that, based on Ikrima ibn Amr, there was a lunar eclipse observed by the non-Islamic Arabs of that time, which Muhammad interpreted as a sign of God to remember the transience of creation.[209]

Other Islamic tradition credits Muhammad with the miracle of the splitting of the Moon. Already beginning in early post-Quranic tradition, Muqatil ibn Sulayman begins his commentary on the Moon passage with an overview of impending Judgement Day.[210]

Sulayman describes that Muhammad's opponents asked him to display a miracle as a proof of his prophethood. Muhammad is said to have split the Moon into two halves as a proof, whereupon his adversaries proclaimed that this was just an enchantment, and the Moon was united again.[210] In this version, the splitting of the Moon does not occur by accident but on demand.[210] The same account is recorded by Anas ibn Malik who adds Abd Allah ibn Mas'ud as an eyewitness of the split Moon, eventually also being accepted in the canonical hadith compilations.[211]

Animals

According to Islamic interpretation of Surah 9:40, Muhammad and his close friend, usually identified with Abu Bakr,[212] were persecuted by the Quraish on their way to Medina. When they hid themselves in a cave of Mount Thawr, a spider wove a net across the entrance and a dove built a nest, making the persecutors think no one had entered the cave for a long time, saving the prophet and his companion.[213][214] This story led to sanction Muslims from killing a spider in the wider Islamic tradition.[215] In Sufi thought, the event of the web was understood to be a manifestation of the universal web veiling the unbelievers from the divine light, symbolized in Muhammad.[213]

Although not reported in a canonical written corpus,[216] and thus also doubted by some Muslims,[183] many Muslims believe Muhammad had a favorite cat called Muezza (or Muʿizza; Arabic: معزة).[217][218] Muhammad threatened people who hurt or abuse cats with hell.[219] Cats are generally evaluated positively in Muslim society and believed to be ritually pure.[220]

Visual representation

Although Islam only explicitly condemns depicting the divinity, the prohibition was sometimes expanded to prophets and saints and among Arab Sunnism, to any living creature.[221] Thomas Walker Arnold argues that visual representations of Muhammad are rare and if given, usually with his face veiled.[222] He argues that both the Sunni schools of law and the Shia jurisprudence alike prohibit the figurative depiction of Muhammad,[223] and that occurrence of Muhammadin Arabic and Ottoman Turkish arts, flourishing during the Ilkhanate (1256–1353), Timurid (1370–1506), and Safavid (1501–1722) periods, are due to a secular attitude of the time and a religious deviance.

In contrast, Barbara Brend argues that the absence of depictions of Muhammad are best explained by an overthrow of the Arab ruling dynasties by the Turks.[224] In contrast to Arnold's proposition, figurative arts in the 14th-17th flourished among religious zealots who attempted to implement sharīʿah-law, thus, cannot be considered secular or religiously deviants.[225] Prior to the Turkic rulers, figurative arts were boasted by Arabic speaking caliphats of Baghdad, Cairo, and Cordova, as well and enjoyed prestige among both orthodox Sunni circles as well as Shia Muslims.[226]

In artistic depictions, Muhammad's face is often blurred out by light or veiled in Islamic paintings, even when he is depicted, since Muhammad is described as having a face of radiant like light.[24]

See also

- Children of Muhammad

- List of biographies of Muhammad

- Islamic mythology

- Muhammad and the Bible

- Muhammad in the Quran

- Relics of Muhammad

- Stories of The Prophets

Notes

- ^ Opinions about the exact date of Muhammad's birth slightly vary. Shibli Nomani and Philip Khuri Hitti fixed the date to be 571 CE. But August 20, 570 CE is generally accepted. See Muir, vol. ii, pp. 13–14 for further information.

References

- ^ a b * Conrad, Lawrence I. (1987). "Abraha and Muhammad: some observations apropos of chronology and literary topoi in the early Arabic historical tradition1". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 50 (2): 225–40. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00049016. S2CID 162350288.

- Sherrard Beaumont Burnaby (1901). Elements of the Jewish and Muhammadan calendars: with rules and tables and explanatory notes on the Julian and Gregorian calendars. G. Bell. p. 465.

- Hamidullah, Muhammad (February 1969). "The Nasi', the Hijrah Calendar and the Need of Preparing a New Concordance for the Hijrah and Gregorian Eras: Why the Existing Western Concordances are Not to be Relied Upon" (PDF). The Islamic Review & Arab Affairs: 6–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2012.

- ^ Theuma, Edmund. "Qur'anic exegesis: Muhammad & the Jinn." (1996).

- ^ a b c d Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-19-511233-7.

- ^ Esposito (2002b), pp. 4–5.

- ^ Peters, F.E. (2003). Islam: A Guide for Jews and Christians. Princeton University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-691-11553-5.

- ^ Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 12. ISBN 978-0-19-511234-4.

- ^ "Muhammad (prophet)". Microsoft® Student 2008 [DVD] (Encarta Encyclopedia). Redmond, WA: Microsoft Corporation. 2007.

- ^ "The Quran | World Civilization". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2024-06-28.

- ^ Muir, William (1861). Life of Mahomet. Vol. 2. London: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shibli Nomani. Sirat-un-Nabi. Vol 1 Lahore.

- ^ a b Hitti, Philip Khuri (1946). History of the Arabs. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 116.

- ^ "Muhammad". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2013. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Matt Stefon, ed. (2010). Islamic Beliefs and Practices. New York City: Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-61530-060-0.

- ^ a b Matt Stefon (2010). Islamic Beliefs and Practices, p. 18

- ^ a b Morgan, Garry R (2012). Understanding World Religions in 15 Minutes a Day. Baker Books. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4412-5988-2. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Mead, Jean (2008). Why Is Muhammad Important to Muslims. Evans Brothers. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-237-53409-7. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Riedling, Ann Marlow (2014). Is Your God My God. WestBow Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4908-4038-3. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Norman Calder, Jawid Mojaddedi, Andew Rippin “Classical Islam A sourcebook of religious literature” Routledge Tayor & Francis Group 2003 p. 16

- ^ a b c Brannon, Wheeler. "Prophets in the Quran: An introduction to the Quran and Muslim exegesis." A&C Black (2002).

- ^ Brend, Barbara. "Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzād of Herāt (1465–1535). By Michael Barry. p. 308. Paris, Flammarion, 2004." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 17.1 (2007): 308.

- ^ Virani, Shafique N. (2011). "Taqiyya and Identity in a South Asian Community". The Journal of Asian Studies. 70 (1): 99–139. doi:10.1017/S0021911810002974. ISSN 0021-9118. S2CID 143431047. p. 128.

- ^ Khalidi, T. (2009). Images of Muhammad: Narratives of the Prophet in Islam Across the Centuries. USA: Doubleday. p. 209

- ^ Ibn al-'Arabi, Muhyi al-Din (1164–1240), The 'perfect human' and the Muhammadan reality Archived 2011-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Gruber, Christiane. "Between logos (Kalima) and light (Nūr): representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic painting." Muqarnas, Volume 26. Brill, 2009. 229-262.

- ^ Gruber, Christiane. "Between logos (Kalima) and light (Nūr): representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic painting." Muqarnas, Volume 26. Brill, 2009.

- ^ Rustom, Mohammed. "Devil’s advocate: ʿAyn al-Quḍāt’s defence of Iblis in context." Studia Islamica 115.1 (2020): 87

- ^ Korangy, Alireza, Hanadi Al-Samman, and Michael Beard, eds. The beloved in Middle Eastern literatures: The culture of love and languishing. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017. p. 90-96

- ^ A.J. Wensinck, Muʿd̲j̲iza, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ Schimmel, A. (2014). And Muhammad Is His Messenger: The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety. USA: University of North Carolina Press. chapter 7

- ^ a b Brockopp, Jonathan E., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 46

- ^ Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-253-21627-4.

- ^ a b c d e Juan E. Campo, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Facts on File. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1 https://books.google.com/books?id=OZbyz_Hr-eIC&pg=PA494. Archived from the original on 2015-09-30.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Clark, Malcolm (2003). Islam for Dummies. Indiana: Wiley Publishing Inc. p. 100. ISBN 9781118053966. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- ^ "Muhammad". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Esposito, John L., ed. (2003). "Khatam al-Nabiyyin". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 171.

Khatam al-Nabiyyin: Seal of the prophets. Phrase occurs in Quran 33:40, referring to Muhammad, and is regarded by Muslims as meaning that he is the last of the series of prophets that began with Adam.

- ^ Mir, Mustansir (1987). "Seal of the Prophets, The". Dictionary of Qur'ānic Terms and Concepts. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 171.

Muḥammad is called "the seal of the prophets" in 33:40. The expression means that Muḥammad is the final prophet, and that the institution of prophecy after him is "sealed."

- ^ Hughes, Thomas Patrick (1885). "K͟HĀTIMU 'N-NABĪYĪN". A Dictionary of Islam: Being a Cyclopædia of the Doctrines, Rites, Ceremonies, and Customs, Together with the Technical and Theological Terms, of the Muhammadan Religion. London: W. H. Allen. p. 270. Archived from the original on 2015-10-04.

K͟HĀTIMU 'N-NABĪYĪN (خاتم النبيين). "The seal of the Prophets." A title assumed by Muhammad in the Qur'ān. Surah xxxiii. 40: "He is the Apostle of God and the 'seal of the Prophets'." By which is meant, that he is the last of the Prophets.

- ^ Coeli Fitzpatrick; Adam Hani Walker, eds. (2014). "Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God [2 volumes]". Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God. ABC-CLIO. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-61069-178-9. Archived from the original on 2016-04-27.

- ^ Bogle, Emory C. (1998). Islam: Origin and Belief. University of Texas Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-292-70862-4. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Goldziher, Ignác (1981). "Sects". Introduction to Islamic Theology and Law. Translated by Andras and Ruth Hamori from the German Vorlesungen über den Islam (1910). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 220–21. ISBN 0691100993. Archived from the original on 2015-10-05.

Sunnī and Shī'ī theology alike understood it to mean that Muhammad ended the series of Prophets, that he had accomplished for all eternity what his predecessors had prepared, that he was God's last messenger delivering God's last message to mankind.

- ^ Martin, Richard C., ed. (2004). "'Ali". Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Vol. 1. New York: Macmillan. p. 37.

- ^ Marion Holmes Katz The Birth of The Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam Routledge 2007 ISBN 978-1-135-98394-9 page 13

- ^ Marion Holmes Katz The Birth of The Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam Routledge 2007 ISBN 978-1-135-98394-9 page 13

- ^ G. Widengren Historia Religionum, Volume 2 Religions of the Present, Band 2 Brill 1971 ISBN 978-9-004-02598-1 page 177

- ^ Goldziher, Ignaz. "Neuplatonische und gnostische Elemente im Ḥadῑṯ." (1909): 317-344.

- ^ a b M.J. Kister Adam: A Study of Some Legends in Tafsir and Hadit Literature Approaches to the History of the Interpretation of The Qur'an, Oxford 1988 p. 129

- ^ a b Brockopp, Jonathan E., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 169

- ^ Sufism: love & wisdom Jean-Louis Michon, Roger Gaetani 2006 ISBN 0-941532-75-5 p. 242

- ^ Brockopp, Jonathan E., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 159-161

- ^ Brockopp, Jonathan E., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 163

- ^ Brockopp, Jonathan E., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 166

- ^ Brockopp, Jonathan E., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 163-169

- ^ Brockopp, Jonathan E., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 173-178

- ^ Rustom, Mohammed. "The cosmology of the Muhammadan Reality." Ishrāq: Islamic Philosophy Yearbook 4 (2013): 540-5.

- ^ Rom Landau The Philosophy of Ibn 'Arabi Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-1-135-02969-2

- ^ a b Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-253-21627-4.

- ^ Khadduri, Majid (1984). The Islamic Conception of Justice. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8018-6974-7.

- ^ "Sunnah." In The Islamic World: Past and Present. Ed. John L. Esposito. Oxford Islamic Studies Online. 22-Apr-2013. "Sunnah - Oxford Islamic Studies Online". Archived from the original on 2014-04-19. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ a b Nigosian (2004), p. 80

- ^ Muhammad Taqi Usmani (2004). The Authority of Sunnah. p. 6. Archived from the original on 2015-10-22.

- ^ a b Stefon, Islamic Beliefs and Practices, p. 59

- ^ a b Shoemaker, Stephen J. The Death of a Prophet: The End of Muhammad's Life and the Beginnings of Islam. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. p. 75

- ^ Khalidi, T. (2009). Images of Muhammad: Narratives of the Prophet in Islam Across the Centuries. USA: Doubleday. p. 18

- ^ a b Raven, W. (2011). Biography of the Prophet. In K. Fleet, G. Krämer, D. Matringe, J. Nawas and D. J. Stewart (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Islam Three Online. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23716

- ^ Ali, Kecia. The lives of Muhammad. Harvard University Press, 2014. p. 461

- ^ Ali, Kecia. The lives of Muhammad. Harvard University Press, 2014. p. 465

- ^ a b Hagen, Gottfried. "The imagined and the historical Muhammad." (2009): 97-111.

- ^ Sell, Edward (1913). The Life of Muhammad (PDF). Madras. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Josiane Cauquelin, Paul Lim, Birgit Mayer-Koenig Asian Values: Encounter with Diversity Routledge 2014 ISBN 978-1-136-84125-5

- ^ Brockopp, Jonathan E., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 141

- ^ a b Katz, M. H. (2017). Birthday of the Prophet. In K. Fleet, G. Krämer, D. Matringe, J. Nawas and D. J. Stewart (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Islam Three Online. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_24018

- ^ a b Katz, M. H. (2007). The Birth of The Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam. Vereinigtes Königreich: Taylor & Francis. p. 13

- ^ Katz, M. H. (2007). The Birth of The Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam. Vereinigtes Königreich: Taylor & Francis. p. 15

- ^ Brockopp, Jonathan E., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 127

- ^ Katz, M. H. (2007). The Birth of The Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam. Vereinigtes Königreich: Taylor & Francis. p. 14

- ^ Marion Holmes Katz The Birth of The Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam Routledge 2007 ISBN 978-1-135-98394-9 page 14

- ^ Rubin, U., “Nūr Muḥammadī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 4 December 2023 doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_5985 First published online: 2012 First print edition: ISBN 9789004161214, 1960-2007

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- ^ Article "AL-SHĀM" by C.E. Bosworth, Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume 9 (1997), page 261.

- ^ Kamal S. Salibi (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. I.B.Tauris. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-1-86064-912-7. Archived from the original on 2016-05-16.

To the Arabs, this same territory, which the Romans considered Arabian, formed part of what they called Bilad al-Sham, which was their own name for Syria. From the classical perspective however Syria, including Palestine, formed no more than the western fringes of what was reckoned to be Arabia between the first line of cities and the coast. Since there is no clear dividing line between what are called today the Syrian and Arabian deserts, which actually form one stretch of arid tableland, the classical concept of what actually constituted Syria had more to its credit geographically than the vaguer Arab concept of Syria as Bilad al-Sham. Under the Romans, there was actually a province of Syria, with its capital at Antioch, which carried the name of the territory. Otherwise, down the centuries, Syria like Arabia and Mesopotamia was no more than a geographic expression. In Islamic times, the Arab geographers used the name arabicized as Suriyah, to denote one special region of Bilad al-Sham, which was the middle section of the valley of the Orontes river, in the vicinity of the towns of Homs and Hama. They also noted that it was an old name for the whole of Bilad al-Sham which had gone out of use. As a geographic expression, however, the name Syria survived in its original classical sense in Byzantine and Western European usage, and also in the Syriac literature of some of the Eastern Christian churches, from which it occasionally found its way into Christian Arabic usage. It was only in the nineteenth century that the use of the name was revived in its modern Arabic form, frequently as Suriyya rather than the older Suriyah, to denote the whole of Bilad al-Sham: first of all in the Christian Arabic literature of the period, and under the influence of Western Europe. By the end of that century it had already replaced the name of Bilad al-Sham even in Muslim Arabic usage.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- ^ Ali, Muhammad (2011). Introduction to the Study of The Holy Qur'an. Ahmadiyya Anjuman Ishaat Islam Lahore USA. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-934271-21-6. Archived from the original on 2015-10-29.

- ^ Muir, William (1861). Life of Mahomet. Vol. 2. London: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. xvii-xviii. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ^ Stefon, Islamic Beliefs and Practices, pp. 22–23

- ^ Al Mubarakpuri, Safi ur Rahman (2002). Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum (The Sealed Nectar). Darussalam. p. 74. ISBN 978-9960-899-55-8. Archived from the original on 2015-10-31.

- ^ a b Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- ^ Sell (1913), p. 12

- ^ Ramadan, Tariq (2007). In the Footsteps of the Prophet: Lessons from the Life of Muhammad. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-530880-8.

- ^ Stefon, Islamic Beliefs and Practices, p. 24

- ^ Wheeler, Historical Dictionary of Prophets in Islam and Judaism, "Noah"

- ^ a b Brown, Daniel (2003). A New Introduction to Islam. Blackwell Publishing Professional. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-631-21604-9.

- ^ a b Sell, Edward (1913). The Life of Muhammad. Madras: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 29.

- ^ Bennett, Clinton (1998). In Search of Muhammad. London: Cassell. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-304-70401-9.

- ^ Bogle, Emory C. (1998). Islam: Origin and Belief. Texas University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-292-70862-4.

- ^ Campo (2009), p. 494

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon. "Prophets in the Quran." Prophets in the Quran (2002): 1-400.

- ^ Brockopp, Jonathan E., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 178

- ^ Donner, Fred M. Muhammad and the Believers. Harvard University Press, 2010. p. 40-41

- ^ "Muhammad and the Quran". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Juan E. Campo, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Facts on File. pp. 570–573. ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1 https://books.google.com/books?id=OZbyz_Hr-eIC&pg=PA570.

The Quran is the sacred scripture of Islam. Muslims believe it contains the infallible word of God as revealed to Muhammad the Prophet in the Arabic language during the latter part of his life, between the years 610 and 632… (p. 570). Quran was revealed piecemeal during Muhammad's life, between 610 C.E. and 632 C.E., and that it was collected into a physical book (mushaf) only after his death. Early commentaries and Islamic historical sources support this understanding of the Quran's early development, although they are unclear in other respects. They report that the third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656) ordered a committee headed by Zayd ibn Thabit (d. ca. 655), Muhammad's scribe, to establish a single authoritative recension of the Quran… (p. 572-3).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Oliver Leaman, ed. (2006). The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 520. ISBN 9-78-0-415-32639-1 https://books.google.com/books?id=isDgI0-0Ip4C&pg=PA520.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Matt Stefon, ed. (2010). Islamic Beliefs and Practices. New York City: Britannica Educational Publishing. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-1-61530-060-0.

- ^ Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 65–68. ISBN 978-0-253-21627-4.

- ^ Donner, Fred M. Muhammad and the Believers. Harvard University Press, 2010. p. 41

- ^ a b Juan E. Campo, ed. (2009). "Muhammad". Encyclopedia of Islam. Facts on File. p. 493. ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1.

- ^ Hitti, Philip Khuri (1946). History of the Arabs. Macmillan and Co. pp. 113–4.

- ^ Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- ^ a b Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- ^ Hitti, Philip Khuri (1946). History of the Arabs. Macmillan and Co. p. 114.

- ^ Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- ^ a b Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan A.C. (2011). Muhammad: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-955928-2. Archived from the original on 2017-02-16.

- ^ Al-Mubarakpuri (2002). The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet. Darussalam. p. 165. ISBN 978-9960-899-55-8.

- ^ Sell, Edward (1913). The Life of Muhammad. Madras: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 70.

- ^ a b Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- ^ Sell, Edward (1913). The Life of Muhammad. Madras: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 71.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 70–1. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- ^ Sell, Edward (1913). The Life of Muhammad. Madras: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 76.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

Accordingly, within a very short period, despite the opposition of the Quraysh, most of the Muslims in Mecca managed to migrate to Yathrib.

- ^ a b Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S., Lambton; Lewis, Bernard, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- ^ "Ya-Seen Ninth Verse". Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b Shaikh, Fazlur Rehman (2001). Chronology of Prophetic Events. London: Ta-Ha. pp. 51–52.

- ^

- Shamsi, F. A. (1984). "The date of hijrah". Islamic Studies. 23 (3). Islamabad: Islamic Research Institute, International Islamic University: 189–224. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20847270.

- Shamsi, F. A. (1984). "The date of hijrah". Islamic Studies. 23 (4). Islamabad: Islamic Research Institute, International Islamic University: 289–323. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20847277.

- ^ Armstrong (2002), p. 14

- ^ Campo (2009), Muhammad, Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 493

- ^ Halverson, Jeffry R., et al. "The Battle of Badr." Master Narratives of Islamist Extremism (2011): 49-56.

- ^ a b Halverson, Jeffry R., et al. "The Battle of Badr." Master Narratives of Islamist Extremism (2011): 50.

- ^ a b Zwemer, M. Samuel. Studies In Popular Islam. London, 1939. p. 27

- ^ Müller, Mathias. "Signs of the Merciful." Journal of Religion and Violence 7.2 (2019): 91-127.

- ^ Muhammad Shafi Usmani (1986). Tafsir Maariful Quran. Vol. 4. Lahore. p. 163.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Al-Mubarakpuri (2002). The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet. Darussalam. p. 253. ISBN 978-9960-899-55-8.

- ^ Watt, W. Montgomery (1956). Muhammad at Medina. Oxford University Press. p. 11.

- ^ a b c Rubin, Uri. "Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam." (1979): 46.

- ^ YOUNG, M. J. L. (1966). "THE TREATMENT OF THE PRINCIPLE OF EVIL IN THE QUR'ĀN". Islamic Studies. 5 (3): 275–281. JSTOR 20832847. Retrieved November 7, 2021. p. 280

- ^ Burge, Stephen Russell. "Angels in Islam: a commentary with selected translations of Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī’s Al-Ḥabā’ik fī akhbār almalā’ik (The Arrangement of the Traditions about Angels)." (2010). p. 414

- ^ Halverson, Jeffry R., et al. "The Battle of Badr." Master Narratives of Islamist Extremism (2011): 49.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- ^ Al Mubarakpuri (2002). "Ar-Raji Mobilization". The Sealed Nectar. Darussalam. ISBN 9789960899558. Archived from the original on 2013-05-27.

- ^ Peterson, Muhammad: the prophet of God, p. 125-127.

- ^ Brown, A New Introduction to Islam, p. 81.

- ^ Lings, Martin (1987). Muhammad: His Life Based on Earliest Sources. Inner Traditions International Limited. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-89281-170-0.

- ^ Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-253-21627-4.

- ^ Lings, Martin (1987). Muhammad: His Life Based on Earliest Sources. Inner Traditions International Limited. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-89281-170-0.

- ^ Muhammad Zafrullah Khan (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 225. ISBN 9780710006103. Archived from the original on 2015-10-25.

- ^ Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-253-21627-4.

- ^ Khan, Majid Ali (1998), p. 274