Mourning

Mourning is the expression[2] of an experience that is the consequence of an event in life involving loss,[3] causing grief.[2] It typically occurs as a result of someone's death, often (but not always) someone who was loved,[3] although loss from death is not exclusively the cause of all experience of grief.[4]

The word is used to describe a complex of behaviors in which the bereaved participate or are expected to participate, the expression of which varies by culture.[2] Wearing black clothes is one practice followed in many countries, though other forms of dress are seen.[5] Those most affected by the loss of a loved one often observe a period of mourning, marked by withdrawal from social events and quiet, respectful behavior in some cultures, though in others mourning is a collective experience.[6] People may follow religious traditions for such occasions.[6]

Mourning may apply to the death of, or anniversary of the death of, an important individual such as a local leader, monarch, religious figure, or member of family. State mourning may occur on such an occasion. In recent years, some traditions have given way to less strict practices, though many customs and traditions continue to be followed.[7]

Death can be a release for the mourner, in the case of the death of an abusive or tyrannical person, or when death terminates the long, painful illness of a loved one. However, this release may add remorse and guilt for the mourner.

Stages of grief

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

Mourning is a personal and collective response which can vary depending on feelings and contexts. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross's theory of grief describes five separate periods of experience in the psychological and emotional processing of death. These stages do not necessarily follow each other, and each period is not inevitable.[8][9] The theory was originally posited to describe the experiences of those confronted with their imminent deaths, but has since been adopted to understand the experiences of bereaved loved ones.[10] The theory has faced criticism for being overly prescriptive and lacking evidence.[11][12]

- Shock, denial: A phase characterized by the refusal of the griever to accept news of a loved ones death or terminal illness. Typically a shorter period which exists as a defense mechanism in the case of a distressing situation.[12]

- Anger: This phase is characterized by a sense of outrage due to the loss, accompanied by guilt in some cases. The anger response typically involves blaming other for the loss, potentially including higher powers.[12]

- Bargaining: This phase sees a person engage in internal or external bargaining and negotiation.[12]

- Depression: The depression phase can be the longest phase of the mourning process, characterized by great sadness, questioning, and distress. An allowance of the pain from which the first three stages may be defense mechanisms.[12] Mourners in this phase sometimes feel that they will never complete their mourning. They have experienced a wide range of emotions and their sorrow is great.

- Acceptance: The last stage of mourning, where the bereaved gets better. The reality of the loss is much more understood and accepted. The bereaved can still feel sadness, but has regained full functioning and has also reorganized life adjusting to the loss.

The five stages can be understood in terms of both psychological and social responses.

- Psychological: When someone close to a person dies, the person enters a period of sorrow and questioning, or even nervous breakdown. There are three stages in the grieving process, encompassing the denial, depression and acceptance phases of Kübler-Ross' five step model.[10]

- Social: The feelings and mental state of the mourner affect their ability to maintain or enter into relationships with others, including professional, personal and sexual relationships.[13] After the customs of burying or cremating the deceased, many cultures follow a number of socially-prescribed traditions that may affect the clothing a person wears and what activities they can partake in.[5] These traditions are generally determined by the degree of kinship to and the social importance of the deceased.

There are various other models for understanding grief. Examples of these include: the Bowlby and Parkes' Four Phases of Grief, Worden's Four Basic Tasks In Adapting To Loss, Wolfelt's Companioning Approach to Grieving, Neimeyer's Narrative and Constructivist Model, the Stroebe and Schut model and the Okun and Nowinski model[12][14]

Social customs and dress

[edit]Africa

[edit]Ethiopia

[edit]In Ethiopia, an Edir (variants eddir and idir in the Oromo language) is a traditional community organization whose members assist each other during the mourning process.[15][16] Members make monthly financial contributions forming the Edir's fund. They are entitled to receive a certain sum of money from this fund to help cover funeral and other expenses associated with deaths.[16] Additionally, Edir members comfort the mourners: female members take turns doing housework, such as preparing food for the mourning family, while male members usually take the responsibility to arrange the funeral and erect a temporary tent to shelter guests who come to visit the mourning family.[16] Edir members will stay with the mourning family and comfort them for a week or more, during which time the family is never alone.[16]

Nigeria

[edit]In Nigeria, there is a cultural belief that a recent widow is impure. During the mourning period, which lasts from 3 months to a year, several traditions are enforced for the purpose of purification, including confinement, complete shaving of the widow and her children, and a ban on any hygiene practices- including hand-washing, wearing clean clothes or sitting off the floor when eating.[17] The extended family of the husband also take all the widow's property. These practices are criticized for the health risks and emotional damage to the widow.[17]

Asia

[edit]East Asia

[edit]White is the traditional color of mourning in Chinese culture, with white clothes and hats formerly having been associated with death.[18] In imperial China, Confucian mourning obligations required even the emperor to retire from public affairs upon the death of a parent. The traditional period of mourning was nominally 3 years, but usually 25–27 lunar months in practice, and even shorter in the case of necessary officers; the emperor, for example, typically remained in seclusion for just 27 days.

The Japanese term for mourning dress is mofuku (喪服), referring to either primarily black Western-style formal wear or to black kimono and traditional clothing worn at funerals and Buddhist memorial services. Other colors, particularly reds and bright shades, are considered inappropriate for mourning dress. If wearing Western clothes, women may wear a single strand of white pearls. Japanese-style mourning dress for women consists of a five-crested plain black silk kimono, a black obi and black accessories worn over white undergarments, black zōri and white tabi. Men's mourning dress consists of clothing worn on extremely formal occasions: a plain black silk five-crested kimono and black and white, or gray and white, striped hakama trousers over white undergarments, a black crested haori jacket with a white closure, white or black zōri and white tabi. It is customary for Japanese-style mourning dress to be worn only by the immediate family and very close friends of the deceased; other attendees wear Western-style mourning dress or subdued Western or Japanese formal clothes.

Southeast Asia

[edit]In Thailand, people wear black when attending a funeral. Black is considered the mourning color, although historically it was white. Widows may wear purple when mourning the death of their spouse.[19]

In the Philippines, mourning customs vary and are influenced by Chinese and folk Catholic beliefs. The immediate family traditionally wear black, with white as a popular alternative.[20] Others may wear subdued colors when paying respects, with red universally considered taboo and bad luck when worn within 9–40 days of a death as the color is reserved for happier occasions. Those who wear uniforms are allowed to wear a black armband above the left elbow, as do male mourners in barong tagalog. The bereaved, should they wear other clothes, attach a small scrap of black ribbon or a black plastic pin on the left breast, which is disposed of after mourning. Flowers are an important symbol in Filipino funerals.[20] Consuming chicken during the wake and funeral is believed to bring more death to the bereaved, who are also forbidden from seeing visitors off. Counting nine days from moment of death, a novena of Masses or other prayers, known as the pasiyám (from the word for "nine"), is performed; the actual funeral and burial may take place within this period or after. The spirit of the dead is believed to roam the earth until the 40th day after death, when it is said to cross into the afterlife, echoing the 40 days between Christ's Resurrection and Ascension into Heaven. The immediate family on this day have another Mass said followed by a small feast, and do so again on the first death anniversary. This is the Babáng-luksâ, which is the commonly accepted endpoint of official mourning.

West Asia

[edit]In the Assyrian tradition, just after a person passes away, the mourning family host guests in an open house style. Only bitter coffee and tea are served, showcasing the sorrowful state of the family. On the funeral day, a memorial mass is held in the church. At the graveyard, the people gather and burn incense around the grave as clergy chant hymns in the Syriac language. The closest female relatives traditionally bewail or lament in a public display of grief as the casket descends. A few others may sing a dirge or a sentimental threnody. During all these occasions, everyone is expected to dress completely in black. Following the burial, everyone returns to the church hall for afternoon lunch and eulogy. At the hall, the closest relatives sit on a long table facing the guests as many people walk by and offer their condolences. On the third day, mourners customarily visit the grave site with a pastor to burn incense, symbolizing Jesus' triumph over death on the third day. This is also done 40 days after the funeral (representing Jesus ascending to heaven), and one year later to conclude the mourning period. Mourners wear only black until the 40 day mark and typically do not dance or celebrate any major events for one year.[21][22]

Europe

[edit]Continental Europe

[edit]

The custom of wearing unadorned black clothing for mourning dates back at least to the Roman Empire, when the toga pulla, made of dark-colored wool, was worn during mourning.[23]

Through the Middle Ages and Renaissance, distinctive mourning was worn for general as well as personal loss; after the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of Huguenots in France, Elizabeth I of England and her court are said to have dressed in full mourning to receive the French Ambassador.

Widows and other women in mourning wore distinctive black caps and veils, generally in a conservative version of any current fashion.

In areas of Russia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Greece, Albania, Mexico, Portugal, and Spain, widows wear black for the rest of their lives. The immediate family members of the deceased wear black for an extended time. Since the 1870s, mourning practices for some cultures, even those who have emigrated to the United States, are to wear black for at least two years, though lifelong black for widows remains in some parts of Europe.[dubious – discuss]

In Belgium, the Court went in public mourning after publication in the Moniteur Belge. In 1924, the court went in mourning after the death of Marie-Adélaïde, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg, for 10 days, the duke of Montpensier for five days, and a full month for the death of Princess Louise of Belgium.

White mourning

[edit]

The color of deepest mourning among medieval European queens was white. In 1393, Parisians were treated to the unusual spectacle of a royal funeral carried out in white, for Leo V, King of Armenia, who died in exile.[24] This royal tradition survived in Spain until the end of the 15th century. In 1934, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands reintroduced white mourning after the death of her husband Prince Henry. It has since remained a tradition in the Dutch royal family.

In 2004, the four daughters of Queen Juliana of the Netherlands all wore white to their mother's funeral. In 1993, the Spanish-born Queen Fabiola introduced it in Belgium for the funeral of her husband, King Baudouin. The custom for the queens of France to wear deuil blanc ("white mourning") was the origin of the white wardrobe created in 1938 by Norman Hartnell for Queen Elizabeth (later known as the Queen Mother). She was required to join her husband King George VI on a state visit to France even while mourning her mother.

United Kingdom

[edit]In the present, no special dress or behavior is obligatory for those in mourning in the general population of the United Kingdom, although ethnic groups and religious faiths have specific rituals, and black is typically worn at funerals. Traditionally, however, strict social rules were observed.

Georgian and Victorian eras

[edit]

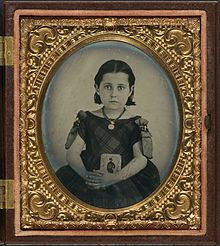

By the 19th century, mourning behavior in England had developed into a complex set of rules, particularly among the upper classes. For women, the customs involved wearing heavy, concealing black clothing, and the use of heavy veils of black crêpe. The entire ensemble was colloquially known as "widow's weeds" (from the Old English wǣd, meaning "garment"), and would comprise either newly-created clothing, or overdyed clothing which the mourner already owned. Up until the later 18th century, the clothes of the deceased, unless they were considerably poor, were still listed in the inventories of the dead, as clothing constituted a relatively high expense.[25] Mourning attire could feature "weepers"—conventional markers of grief such as white cuffs or cuff adornments, black hat-bands, or long black crêpe veils.[26]

Special caps and bonnets, usually in black or other dark colours, went with these ensembles; mourning jewellery, often made of jet, was also worn, and became highly popular in the Victorian era. Jewellery was also occasionally using the hair of the deceased. The wealthy would wear cameos or lockets designed to hold a lock of the deceased's hair or some similar relic.

Social norms could prescribe that widows wore special clothes to indicate that they were in mourning for up to four years after the death, although a widow could choose to wear such attire for a longer period of time, even for the rest of her life. To change one's clothing too early was considered disrespectful to the deceased, and, if the widow was still young and attractive, suggestive of potential sexual promiscuity. Those subject to the rules were slowly allowed to re-introduce conventional clothing at specific times; such stages were known by such terms as "full mourning", "half mourning", and similar descriptions. For half mourning, muted colours such as lilac, grey and lavender could be introduced.[27]

Friends, acquaintances, and employees wore mourning to a greater or lesser degree depending on their relationship to the deceased. Mourning was worn for six months after the death of a sibling.[citation needed] Parents would wear mourning for a child for "as long as they [felt] so disposed".[need quotation to verify] A widow was supposed to wear mourning for two years, and was not supposed to "enter society" for 12 months. No lady or gentleman in mourning was supposed to attend social events while in deep mourning. In general, servants wore black armbands following a death in the household. However, amongst polite company, the wearing of a simple black armband was seen as appropriate only for military men, or for others compelled to wear uniform in the course of their duties—a black armband instead of proper mourning clothes was seen as a degradation of proper etiquette, and to be avoided.[28] In general, men were expected to wear mourning suits (not to be confused with morning suits) of black frock coats with matching trousers and waistcoats. In the later interbellum period (between World War I and World War II), as the frock coat became increasingly rare, the mourning suit consisted of a black morning coat with black trousers and waistcoat, essentially a black version of the morning suit worn to weddings and other occasions, which would normally include coloured waistcoats and striped or checked trousers.

Formal mourning customs culminated during the reign of Queen Victoria (r. 1837–1901), whose long and conspicuous grief over the 1861 death of her husband, Prince Albert, heavily influenced society. Although clothing fashions began to be more functional and less restrictive in the succeeding Edwardian era (1901-1910), appropriate dress for men and women—including that for the period of mourning—was still strictly prescribed and rigidly adhered to. In 2014, The Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibition of women's mourning attire from the 19th century, entitled Death Becomes Her: A Century of Mourning Attire.[29]

The customs were not universally supported, with Charles Voysey writing in 1873 "that it adds needlessly to the gloom and dejection of really afflicted relatives must be apparent to all who have ever taken part in these miserable rites".[30]

The rules gradually relaxed over time, and it became acceptable practice for both sexes to dress in dark colours for up to a year after a death in the family. By the late 20th century, this no longer applied, and women in cities had widely adopted black as a fashionable colour.

North America

[edit]United States

[edit]

Mourning generally followed English forms into the 20th century. Black dress is still considered proper etiquette for attendance at funerals, but extended periods of wearing black dress are no longer expected. However, attendance at social functions such as weddings when a family is in deep mourning is frowned upon.[citation needed] Men who share their father's given name and use a suffix such as "Junior" retain the suffix at least until the father's funeral is complete.[citation needed]

In the antebellum South, with social mores that imitated those of England, mourning was just as strictly observed by the upper classes.

In the 19th century, mourning could be quite expensive, as it required a whole new set of clothes and accessories or, at the very least, overdyeing existing garments and taking them out of daily use. For a poorer family, this was a strain on resources.[31][full citation needed]

At the end of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Dorothy explains to Glinda that she must return home because her aunt and uncle cannot afford to go into mourning for her because it was too expensive.[32]

A late 20th and early 21st century North American mourning phenomenon is the rear window memorial decal. This is a large vinyl window-cling decal memorializing a deceased loved one, prominently displayed in the rear windows of cars and trucks belonging to close family members and sometimes friends. It often contains birth and death dates, although some contain sentimental phrases or designs as well.[33]

The Pacific

[edit]Tonga

[edit]In Tonga, family members of deceased persons wear black for an extended time, with large plain Taʻovala. Often, black bunting is hung from homes and buildings. In the case of the death of royalty, the entire country adopts mourning dress and black and purple bunting is displayed from most buildings.

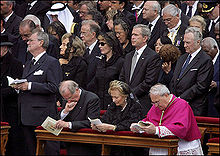

State and official mourning

[edit]

States usually declare a period of "official mourning" after the death of a head of state. in the case of a monarchy, court mourning refers to mourning during a set period following the death of a public figure or member of a royal family. The protocols for mourning vary, but typically include the lowering or posting half-mast of flags on public buildings. In contrast, the Royal Standard of the United Kingdom is not flown at half-mast upon the death of a head of state, as there is always a monarch on the throne.

The degree and duration of public mourning is generally decreed by a protocol officer. It was not unusual for the British court to declare that all citizens should wear full mourning for a specified period after the death of the monarch or that the members of the court should wear full- or half-mourning for an extended time. On the death of Queen Victoria (22 January 1901), the Canada Gazette published an "extra" edition announcing that court mourning would continue until 24 January 1902. It directed the public to wear deep mourning until 6 March 1901 and half-mourning until 17 April 1901. As they had done in earlier years for Queen Victoria, her son King Edward VII, his wife Queen Alexandra and the Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, the royal family went into mourning on the death of Prince Philip in April 2021.[34] The black-and-white costumes designed by Cecil Beaton for the Royal Ascot sequence in My Fair Lady were inspired by the "Black Ascot" of 1910, when the court was in mourning for Edward VII.

The principle of continuity of the State, however, is also respected in mourning, and is reflected in the French saying "Le Roi est mort, vive le Roi!" ("The king is dead, long live the king!"). Regardless of the formalities of mourning, the power of state is handed on, typically immediately if the succession is uncontested. A short interruption of work in the civil service, however, may result from one or more days of closing the offices, especially on the day of the state funeral.

In January 2006, on the death of Jaber Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, the emir of Kuwait, a mourning period of 40 days was declared. In Tonga, the official mourning lasts for a year; the heir is crowned after this period has passed.

Religions and customs

[edit]Confucianism

[edit]There are five grades of mourning obligations in the Confucian Code. A person is expected to honor most of those descended from their great-great-grandfather, and most of their wives. The death of a person's father and mother would merit 27 months of mourning; the death of a person's grandfather on the male side, as well as their grandfather's wife, would be grade two, or necessitate 12 months of mourning. A paternal uncle is grade three, at nine months, with grade four is reserved for one's father's first cousin, maternal grandparents, siblings and sister's children (five months). First cousins once removed, second cousins and the parents of a man's wife's are considered grade five (three months).[35]

Buddhism

[edit]In Buddhism, mourning is an opportunity to practice the core principles of impermanence, non-attachment, and compassion. While Buddhists feel the pain of loss like anyone else, their practices encourage letting go, finding peace, and expressing compassion for both the deceased and themselves. The perspective of rebirth and samsara also brings comfort, as it views death as a transition rather than an end.[citation needed]

Christianity

[edit]Eastern Christianity

[edit]

Orthodox Christians usually hold the funeral either the day after death or on the third day, and always during the daytime. In traditional Orthodox communities, the body of the departed would be washed and prepared for burial by family or friends, and then placed in the coffin in the home. A house in mourning would be recognizable by the lid of the coffin, with a cross on it, and often adorned with flowers, set on the porch by the front door.

Special prayers are held on the third, seventh or ninth (number varies in different national churches), and 40th days after death; the third, sixth and ninth or twelfth month;[36] and annually thereafter in a memorial service,[citation needed] for up to three generations. Kolyva is ceremoniously used to honor the dead.

Sometimes men in mourning will not shave for the 40 days.[citation needed] In Greece and other Orthodox countries, it is not uncommon for widows to remain in mourning dress for the rest of their lives.

When an Orthodox bishop dies, a successor is not elected until after the 40 days of mourning are completed, during which period his diocese is said to be "widowed".

The 40th day has great significance in Orthodox religion, considered the period during which soul of deceased wanders on earth. On the 40th day, the ascension of the deceased's soul occurs, and is the most important day in mourning period, when special prayers are held on the grave site of deceased.

As in the Roman Catholic rites, there can be symbolic mourning. During Holy Week, some temples in the Church of Cyprus draw black curtains across the icons.[37] The services of Good Friday and Holy Saturday morning are patterned in part on the Orthodox Christian burial service, and funeral lamentations.

Western Christianity

[edit]

European social forms are, in general, forms of Christian religious expression transferred to the greater community.

In the Roman Catholic Church, the Mass of Paul VI adopted in 1969 allows several options for the liturgical color used in Masses for the Dead. Before this, black was the ordinary color for funeral Masses except for white in the case of small children; the revised use makes other options available, with black as the intended norm. According to the General Instruction of the Roman Missal (§346d-e), black vestments are to be used at Offices and Masses for the Dead; an indult was given for some countries to use violet or white vestments, and in places those colours have largely supplanted black.

Christian churches often go into symbolic mourning during the period of Lent to commemorate the sacrificial death of Jesus. Customs vary among denominations and include temporarily covering or removing statuary, icons and paintings, and use of special liturgical colours, such as violet/purple, during Lent and Holy Week.

In more formal congregations, parishioners also dress according to specific forms during Holy Week, particularly on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday, when it is common to wear black or sombre dress or the liturgical colour of purple.

Special prayers are held on the third, seventh, and 30th days after death;[38] Prayers are held on the third day, because Jesus rose again after three days in the sepulchre (1 Corinthians 15:4).[39] Prayers are held on the seventh day, because Joseph mourned his father Jacob seven days (Genesis 50:10)[40] and in Book of Sirach is written that "seven days the dead are mourned" (Ecclesiasticus 22:13).[41] Prayers are held on the thirtieth day, because Aaron (Numbers 20:30)[42] and Moses (Deuteronomy 34:8)[43] were mourned thirty days.

Hinduism

[edit]Death is not seen as the final "end" in Hinduism, but is seen as a turning point in the seemingly endless journey of the indestructible "atman", or soul, through innumerable bodies of animals and people. Hence, Hinduism prohibits excessive mourning or lamentation upon death, as this can hinder the passage of the departed soul towards its journey ahead: "As mourners will not help the dead in this world, therefore (the relatives) should not weep, but perform the obsequies to the best of their power."[44]

Hindu mourning is described in dharma shastras.[45][46] It begins immediately after the cremation of the body and ends on the morning of the thirteenth day. Traditionally, the body is cremated within 24 hours after death; however, cremations are not held after sunset or before sunrise. Immediately after the death, an oil lamp is lit near the deceased, and this lamp is kept burning for three days.

Hinduism associates death with ritual impurity for the immediate blood family of the deceased, hence during these mourning days, the immediate family must not perform any religious ceremonies (except funerals), must not visit temples or other sacred places, must not serve the sages (holy men), must not give alms, must not read or recite from the sacred scriptures, nor can they attend social functions such as marriages and parties. The family of the deceased is not expected to serve any visiting guests food or drink. It is customary that the visiting guests do not eat or drink in the house where the death has occurred. The family in mourning are required to bathe twice a day, eat a single simple vegetarian meal, and try to cope with their loss.

On the day on which the death has occurred, the family do not cook; hence usually close family and friends will provide food for the mourning family. White clothing (the color of purity) is the color of mourning, and many will wear white during the mourning period.

The male members of the family do not cut their hair or shave, and the female members of the family do not wash their hair until the 10th day after the death. If the deceased was young and unmarried, the "Narayan Bali" is performed by the Pandits. The Mantras of "Bhairon Paath" are recited. This ritual is performed through the person who has given the Mukhagni (Ritual of giving fire to the dead body).

On the morning of the 13th day, a Śrāddha ceremony is performed. The main ceremony involves a fire sacrifice, in which offerings are given to the ancestors and to gods, to ensure the deceased has a peaceful afterlife. Pind Sammelan is performed to ensure the involvement of the departed soul with that of God. Typically after the ceremony, the family cleans and washes all the idols in the family shrine; and flowers, fruits, water and purified food are offered to the gods. Then, the family is ready to break the period of mourning and return to daily life.

Islam

[edit]

In Shi'a Islam, examples of mourning practices are held annually in the month of Muharram, the first month of Islamic Lunar calendar. This mourning is held in the commemoration of Imam Al Husayn ibn Ali, who was killed along with his 72 companions by Yazid bin Muawiyah. Shi'a Muslims wear black clothes and take out processions on road to mourn on the tragedy at Karbala. Shi'a Muslims also mourn the death of Fatima (one of Muhammad's daughters) and the Shi'a Imams.

Mourning is observed in Islam by increased devotion, receiving visitors and condolences, and avoiding decorative clothing and jewelry. Loved ones and relatives are to observe a three-day mourning period.[47] Widows observe an extended mourning period (Iddah), four months and ten days long,[48] in accordance with the Qur'an 2:234. During this time, she is not to remarry, move from her home, or wear decorative clothing or jewelry.

Grief at the death of a beloved person is normal, and weeping for the dead is allowed in Islam.[49] What is prohibited is to express grief by wailing ("bewailing" refers to mourning in a loud voice), shrieking, tearing hair or clothes, breaking things, scratching faces, or uttering phrases that make a Muslim lose faith.[50]

Directives for widows

[edit]The Qur'an prohibits widows from engaging themselves for four lunar months and ten days after the death of their husbands. According to Qur'an:

As for those of you who die and leave widows behind, let them observe a waiting period of four months and ten days. When they have reached the end of this period, then you are not accountable for what they decide for themselves in a reasonable manner. And Allah is All-Aware of what you do. There is no blame on you for subtly showing interest in ˹divorced or widowed˺ women or for hiding ˹the intention˺ in your hearts. Allah knows that you are considering them ˹for marriage˺. But do not make a secret commitment with them—you can only show interest in them appropriately. Do not commit to the bond of marriage until the waiting period expires. Know that Allah is aware of what is in your hearts, so beware of Him. And know that Allah is All-Forgiving, Most Forbearing.

Islamic scholars consider this directive a balance between mourning a husband's death and protection of the widow from censure that she became interested in remarrying too soon after her husband's death.[51] This is also to ascertain whether or not she is pregnant.[52]

Judaism

[edit]

Judaism looks upon mourning as a process by which the stricken can re-enter into society, and so provides a series of customs that make this process gradual. The first stage, observed as all the stages are by immediate relatives (parents, spouse, siblings and children) is the Shiva (literally meaning "seven"), which consists of the first seven days after the funeral. The second stage is the Shloshim (thirty), referring to the thirty days following the death. The period of mourning after the death of a parent lasts one year. Each stage places lighter demands and restrictions than the previous one in order to reintegrate the bereaved into normal life.

The most known and central stage is Shiva, which is a Jewish mourning practice in which people adjust their behavior as an expression of their bereavement for the week immediately after the burial. In the West, typically, mirrors are covered and a small tear is made in an item of clothing to indicate a lack of interest in personal vanity. The bereaved dress simply and sit on the floor, short stools or boxes rather than chairs when receiving the condolences of visitors. In some cases relatives or friends take care of the bereaved's house chores, as cooking and cleaning. English speakers use the expression "to sit shiva".

During the Shloshim, the mourners are no longer expected to sit on the floor or be taken care of (cooking/cleaning). However, some customs still apply. There is a prohibition on getting married or attending any sort of celebrations and men refrain from shaving or cutting their hair.

Restrictions during the year of mourning include not wearing new clothes, not listening to music and not attending celebrations. In addition, the sons of the deceased recite the Kaddish prayer for the first eleven months of the year during prayer services where there is a quorum of 10 men. The Kaddish prayer is then recited annually on the date of death, usually called the yahrzeit. The date is according to the Hebrew calendar. In addition to saying the Kaddish in the synagogue, a 24-hour memorial candle is lit in the home of the person saying the Kaddish.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Loés, João (22 February 2013). "A volta de Dom Pedro I". istoe.com.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Robben, Antonius C. G. M. (4 February 2009). Robben, Antonius C. G. M. (ed.). Death, Mourning, and Burial A Cross-Cultural Reader (Ebook). Wiley. p. 7. ISBN 9781405137508. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

In Death, Mourning, and Burial, an indispensable introduction to the anthropology of death, readers will find a rich selection of some of the finest ethnographic work on this fascinating topic...

- ^ a b Brennan, Michael (14 January 2009). Mourning and Disaster Finding Meaning in the Mourning for Hillsborough and Diana (Ebook). Cambridge Scholars Publications (published 2008). p. 2. ISBN 9781443803793. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

The Hillsborough stadium disaster of 15 April 1989 and the death of Princess Diana on 31 August 1997 sparked expressivist scenes of public mourning hitherto unseen within the context of British society...

- ^ Hugstad, Kristi (July 26, 2017). "Grieving Losses Other Than Death". www.huffpost.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "Mourning | Grief, Rituals & Traditions | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-08-19. Retrieved 2024-09-07.

- ^ a b Wilson, John Frederick (2023-01-25). "Death and dying: how different cultures deal with grief and mourning". The Conversation. Retrieved 2024-09-07.

- ^ Rusu, Mihai Stelian (2020-01-01). "Nations in black: charting the national thanatopolitics of mourning across European countries". European Societies. 22 (1): 122–148. doi:10.1080/14616696.2019.1616795. ISSN 1461-6696.

- ^ "Understanding the Five Stages of Grief". Cruse Bereavement Care. February 12, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "growing-around-grief". www.cruse.org.uk (Cruse Bereavement Care). Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth (1970). On Death and Dying. Collier Books/Macmillan Publishing Co.

- ^ McCoyd, Judith L. M. (January 2023). "Forget the "Five Stages": Ask the Five Questions of Grief". Social Work (Jan2023) – via EBSCO.

- ^ a b c d e f Tyrrell, Patrick; Harberger, Seneca; Schoo, Caroline; Siddiqui, Waquar (2024), "Kubler-Ross Stages of Dying and Subsequent Models of Grief", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29939662, retrieved 2024-09-07

- ^ McCoy, Berly (20 December 2021). "How your brain copes with grief, and why it takes time to heal". NPR. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ Schut, H; Stroebe, MS; van den Bout, J; Terheggen, M (2011). "Beyond the five stages of grief". Harvard Mental Health Letter. 28 (6).

- ^ Wokineh Kelbessa (2001). "Traditional Oromo Attitudes towards the Environment: An Argument for Environmentally Sound Development" (PDF). Social Science Research Report Series (19): 89. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d Mark Banga; Maggie Banga (2012-03-02). "Mourning and healing". Comboni Lay Missionaries. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ a b Edemikpong, H. (n.d.). Widowhood rites: Nigeria Women’s Collective Fights a dehumanizing tradition. EBSCO. https://research.ebsco.com/c/iperyp/viewer/pdf/w4msr6xfgv

- ^ "Psychology of Color: Does a specific color indicate a specific emotion? By Steve Hullfish | July 19, 2012". Archived from the original on March 4, 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ Knos, T. "Colors of Mourning". mysendoff.com. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ a b Sunnexdesk (2014-11-12). "Life, death and love: Filipino funeral customs and practices". SunStar Publishing Inc. Retrieved 2024-09-07.

- ^ Troop, Sarah (22 Jul 2014). "The Hungry Mourner". Modern Loss.

- ^ Benjamin, Yoab. "Assyrian Rituals of Life-Cycle Events". www.aina.org. Retrieved 2024-09-24.

- ^ "Toga pulla | clothing | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-11-06.

- ^ Johan Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages (1919, 1924:41).

- ^ Rothstein, Natalie (1990). Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century In The Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 23.

- ^ "weeper". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "English Funeral and mourning clothing". England: The Other Within: Analysing the English Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum. Oxford University. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ The Universal Cyclopædia, W. Ralston Balch, Griffith Farran Okeden & Welsh, London, c. 1887

- ^ "Death Becomes Her: A Century of Mourning Attire". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- ^ Voysey, Charles (31 March 1873). The Custom of Wearing Mourning. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ See Taylor, Jupp and Litten.

- ^ L. Frank Baum, Michael Patrick Hearn (1973). The Annotated Wizard of Oz. C. N. Potter. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-517-50086-6.

- ^ Engel, Allison (December 11, 2005). "In the Rear Window, Tributes to the Dead". New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Holt, Bethan (15 April 2021). "The fascinating history of royal family mourning dress codes". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia B. (1993). The Inner Quarters. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-520-08156-7.

- ^ "Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain – Funerals & Memorials". Thyateira.org.uk. Retrieved 2014-04-17.

- ^ Clark, V. (2000) Why Angels Fall: A Journey Through Orthodox Europe from Byzantium to Kosovo (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan)

- ^ Skg, Admin. "Почему католики отмечают 7 дней и 30 дней после смерти человека?". sib-catholic.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ "Vulgate - Douay-Rheims - Knox Bible side by side". catholicbible.online. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ "Vulgate - Douay-Rheims - Knox Bible side by side". catholicbible.online. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ "Vulgate - Douay-Rheims - Knox Bible side by side". catholicbible.online. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ "Vulgate - Douay-Rheims - Knox Bible side by side". catholicbible.online. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ "Vulgate - Douay-Rheims - Knox Bible side by side". catholicbible.online. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ Viṣṇu smṛti 20.30

- ^ Viṣṇu smṛti 20.30–40

- ^ Āpastamba dharma sūtra 2.6.15.6–9

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari 1279

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari 1280

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari 1304

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari 1306

- ^ Islahi(1986), pp. 546

- ^ Saleem, Shehzad (March 2004). "The Social Directives of Islam: Distinctive Aspects of Ghamidi's Interpretation". Renaissance Islamic Journal. Lahore: Al-Mawrid. Archived from the original on 2007-04-03.

Bibliography

[edit]- The Canada Gazette

- Clothing of Ancient Rome

- Charles Spencer, Cecil Beaton: Stage and Film Designs, London: Academy Editions, 1975. (no ISBN)

- Karen Rae Mehaffey, The After-Life: Mourning Rituals and the Mid-Victorians, Lasar Writers Publishing, 1993. (no ISBN)

- Silver, Catherine B. (2007). "Womb Envy: Loss and Grief of the Maternal Body". Psychoanalytic Review. 94 (3): 409–430. doi:10.1521/prev.2007.94.3.409. PMID 17581094. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- "Grief vs. Mourning: What's the Difference?". www.therecoveryvillage.com. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

External links

[edit]- The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning By Maurice Lamm

- To Those Who Mourn a Christian view by Max Heindel