Mount Graham red squirrel

| Mount Graham red squirrel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Sciuridae |

| Genus: | Tamiasciurus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | T. f. grahamensis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Tamiasciurus fremonti grahamensis (J. A. Allen, 1894)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Mount Graham red squirrel (Tamiasciurus fremonti grahamensis) is an endangered subspecies of the southwestern red squirrel (Tamiasciurus fremonti)[5] native to the Pinaleño Mountains of Arizona. It is smaller than most other subspecies of red squirrel, and also does not have the white-fringed tail that is common to the species. Its diet consists mainly of mixed seeds, conifer cones and air-dried fungi. It exhibits similar behavior to other squirrels in its species.

Description

[edit]Physical

[edit]The Mount Graham red squirrel is a generally tiny squirrel weighing on average around 8 ounces (230 g) and measuring about 8 inches (20 cm) in length.[2] The subspecies also has a 6-inch (15 cm) tail.[2] Unlike most other squirrels in its species, the squirrels do not have a white-fringed tail.[2] Both females and males share similar markings and features and are typically grayish brown in color with rusty yellow or orange markings on their backside.[2] During the winter season, the squirrels' ears are tufted with fur, and during the summer a black lateral line is observed on the squirrel.[2][6] The skull of the subspecies is rounded and its teeth are low-crowned.[6]

Behavior

[edit]Mount Graham red squirrels behave in a manner similar to most other subspecies of American red squirrel. They are diurnal and do not hibernate during the winter months, but instead carry out activities in the mid-day sun.[7] Mount Graham squirrels usually eat a diet of mixed seeds, conifer cones and air-dried fungi.[8]

Habitat

[edit]Historically, the Mount Graham red squirrel inhabited about 11,750 acres (47.6 km2) of spruce-fir, mixed-conifer and ecotone zone habitats that were generally at higher elevations throughout the Pinaleño Mountains.[8] Recent data shows that it occurs more frequently at the ecotone zone than the other habitats.[8] When choosing a potential nesting site, the squirrels typically pick a cool, moist area with an abundance of food sources.[8] Drought, forest fires, and insect infestation have been responsible for a decrease of the squirrel in the spruce-fir habitat.[8]

Conservation

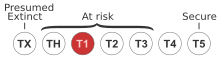

[edit]The Mount Graham subspecies was believed to be extinct in the 1950s, but was "rediscovered" in the 1970s.[9] After its rediscovery, it was suggested for threatened or endangered species status under the Endangered Species Act in 1982.[10] On May 21, 1986, the subspecies was officially recommended to become an endangered species,[11] and effective June 3, 1987, was listed as endangered.[2][3] The Mount Graham International Observatory was controversial when it was built in the squirrel's habitat; the observatory has been required to monitor the community near the observatory to determine if its construction is having any negative effects on the population.[9] Habitat loss is also occurring at high levels for a variety of natural and anthropogenic reasons.[9] In 1988, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service designated most of this area as a refuge, and access to the area is granted only with a special permit.[9] A lightning strike on June 7, 2017, started a wildfire that could have led to the extinction of this subspecies.[12]

In September 2019, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agreed to consider if the squirrel needed further protection. They were petitioned under a procedure of the Endangered Species Act by a group that contends it is necessary to remove the observatory and other private structures.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mount Graham red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus grahamensis)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ a b Shull, Alisa M. (3 June 1987). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Determination of Endangered Status for the Mount Graham Red Squirrel". Federal Register. 52 (106): 20994–20999. 52 FR 20994

- ^ Allen, J.A. (1894). "Descriptions of Five New North American Mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 6: 347–350. Retrieved 6 September 2024 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- ^ "Explore the Database". www.mammaldiversity.org. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ^ a b Fitzpatrick, Lesley; Genice Froehlich; Terry Johnson; Randall Smith; Barry Spicer (May 3, 1993). "Mount Graham red squirrel" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ^ "The Natural History of the Mount Graham Red Squirrel". The University of Arizona. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Mount Graham Red Squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus grahamensis) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Field Office Phoenix, Arizona. January 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d "The Mt. Graham Red Squirrel Research Program Project History". The University of Arizona. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ^ "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Vertebrate Wildlife for Listing as Endangered or Threatened Species" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. December 30, 1982. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ^ Shull, Alisa M. (21 May 1986). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Proposed Determination of Endangered Status and Critical Habitat for the Mount Graham Red Squirrel". Federal Register. 51 (98): 18630–18634. 51 FR 18630

- ^ Albeck-Ripka, Livia (October 25, 2017). "For an Endangered Animal, a Fire or Hurricane Can Mean the End". New York Times.

- ^ "US officials to consider protections for endangered Arizona squirrel". KTAR News. September 5, 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-09-10. Retrieved September 8, 2019.