Mon (emblem)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Mon (紋), also called monshō (紋章), mondokoro (紋所), and kamon (家紋), are Japanese emblems used to decorate and identify an individual, a family, or (more recently) an institution, municipality or business entity. While mon is an encompassing term that may refer to any such device, kamon and mondokoro refer specifically to emblems that are used to identify a family. An authoritative mon reference compiles Japan's 241 general categories of mon based on structural resemblance (a single mon may belong to multiple categories), with 5,116 distinct individual mon. However, it is well acknowledged that there are a number of lost or obscure mon.[1][2] Among mon, the mon officially used by the family is called jōmon (定紋). Over time, new mon have been created, such as kaemon (替紋), which is unofficially created by an individual, and onnamon (女紋), which is created by a woman after marriage by modifying part of her original family's mon, so that by 2023 there will be a total of 20,000 to 25,000 mon.[3]

The devices are similar to the badges and coats of arms in European heraldic tradition, which likewise are used to identify individuals and families. Mon are often referred to as crests in Western literature, the crest being a European heraldic device similar to the mon in function. Japanese mon influenced Louis Vuitton's monogram designs through Japonisme in Europe in the late 1800s.[4][5][6]

History

[edit]

Mon originated in the mid-Heian period (c. 900–1000) as a way to identify individuals and families among the nobility. They had a pecking order, and when gissha (牛車, bullock cart) passed each other on the road, the one with the lower status had to give way, and the mon was painted on the gissha. The Heiji Monogatari Emaki, an emakimono (絵巻物, picture scroll) depicting the Heiji rebellion, shows mon painted on gissha. Gradually, the nobility began to use mon on their own costumes, and the samurai class that emerged in the late Heian period and came to power in the Kamakura period (1185–1333) also began to use mon.[3][7] By the 12th century, sources give a clear indication that heraldry had been implemented as a distinguishing feature, especially for use in battle. It is seen on flags, tents, and equipment. On the battlefield, mon served as army standards, even though this usage was not universal and uniquely designed army standards were just as common as mon-based standards (cf. sashimono, uma-jirushi).

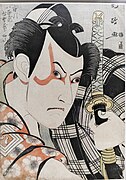

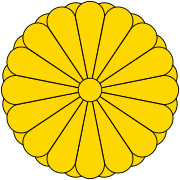

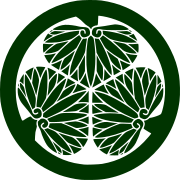

Gradually, mon spread to the lower classes, and in the Muromachi period (1336–1573), merchants painted emblems on their shop signs, which became mon. In the Edo period (1603–1867), kabuki actors used mon, and the general public was allowed to choose and use their favorite mon. By the Genroku period (1680–1709) in the early Edo period, the use of mon was fully established among the general public. However, the use of the chrysanthemum mon used by the imperial family and the hollyhock mon used by the Tokugawa clan (Tokugawa shogunate) was prohibited.[3][7] Mon were also adapted by various organizations, such as merchant and artisan guilds, temples and shrines, theater troupes and even criminal gangs. In an illiterate society, they served as useful symbols for recognition.

-

The mon on the right sleeve of the kimono of Kabuki actor Ichikawa Yaozo III, dressed as Umeōmaru. The kanji 八, meaning 'eight', is written within the triple square. Ukiyo-e (woodblock print) by Utagawa Kunimasa, 1796.

-

The Imperial Seal of Japan—a stylized chrysanthemum blossom

Japanese traditional formal attire generally displays the mon of the wearer. Commoners without mon often used those of their patron or the organization they belonged to. In cases when none of those were available, they sometimes used one of the few mon which were seen as "vulgar", or invented or adapted whatever mon they wished, passing it on to their descendants. It was not uncommon for shops, and therefore shop-owners, to develop mon to identify themselves.

Occasionally, patron clans granted the use of their mon to their retainers as a reward. Similar to the granting of the patron's surnames, this was considered a very high honor. Alternatively, the patron clan may have added elements of its mon to that of its retainer, or chosen an entirely different mon for them.

Design

[edit]

Mon motifs can be broadly classified into five categories: animals, plants, nature, buildings and vehicles, and tools and patterns, each with its own meaning. The most common animal motifs are the crane and the turtle, which, according to tradition, were symbols of longevity and were used to wish the family a long and prosperous life. Plant mon were symbols of wealth and elegance, so they were often used to wish for the improvement of the family's social status and economic power, and motifs such as wisteria and paulownia were often used. Mon depicting buildings, vehicles, or tools often indicated occupation or status. For example, a mon with a torii gate indicated a family associated with Shinto, a mon with a gissha wheel indicated nobility, and a mon with a crowbar indicated a family associated with construction. The mon of nature was a symbol of respect for nature and prayers for a good harvest, and motifs such as the moon, mountains, and thunder were used.[3][7]

The most commonly used mon motifs are wisteria, paulownia, hawk feathers, flowering quince, and creeping woodsorrel, which are called the godaimon (五大紋, five major mon). However, according to a dictionary of mon published by Shogakukan, oak is listed instead of paulownia.[3] There are more than 150 types of wisteria mon, and their use by the Fujiwara clan led to their popularization.[8]

Similar to the blazon in European heraldry, mon are also named by the content of the design, even though there is no set rule for such names. Unlike in European heraldry, however, this "blazon" is not prescriptive—the depiction of a mon does not follow the name—instead the names only serve to describe the mon. The pictorial depictions of the mon are not formalized and small variations of what is supposed to be the same mon can sometimes be seen, but the designs are for the most part standardized through time and tradition.

The degree of variation tolerated differ from mon to mon as well. For example, the paulownia crest with 5-7-5 leaves is reserved for the prime minister, whereas paulownia with fewer leaves could be used by anyone. The imperial chrysanthemum also specifies 16 petals, whereas chrysanthemum with fewer petals are used by other lesser imperial family members.

Japanese heraldry does not have a cadency or quartering system, but it is not uncommon for cadet branches of a family to choose a slightly different mon from the senior branch. Each princely family (shinnōke), for example, uses a modified chrysanthemum crest as their mon. Mon holders may also combine their mon with that of their patron, benefactor or spouse, sometimes creating increasingly complicated designs.

Mon are essentially monochrome; the color does not constitute part of the design and they may be drawn in any color.

Modern usage

[edit]

Virtually all modern Japanese families have a mon, but unlike before the Meiji Restoration when rigid social divisions existed, mon play a more specialized role in everyday life. On occasions when the use of a mon is required, one can try to look up their families in the temple registries of their ancestral hometown or consult one of the many genealogical publications available. Many websites also offer mon lookup services. Professional wedding planners, undertakers and other "ritual masters" may also offer guidance on finding the proper mon.

Mon are seen widely on stores and shops engaged in traditional crafts and specialties. They are favored by sushi restaurants, which often incorporate a mon into their logos. Mon designs can even be seen on the ceramic roof tiles of older houses. Mon designs frequently decorate senbei, sake, tofu and other packaging for food products to lend them an air of elegance, refinement and tradition. The paulownia mon appears on the obverse side of the 500 yen coin.

Items symbolizing family crafts, arts or professions were often chosen as a mon; likewise, mon were, and still are, also passed down a lineage of artists. Geisha typically wear the mon of their okiya (geisha house) on their clothing when working; individual geisha districts, known as hanamachi, also have their own distinctive mon, such as the plover crest (chidori) of Ponto-chō in Kyoto.

A woman may still wear her maiden mon if she wishes and pass it on to her daughters; she does not have to adopt her husband's or father's mon. Flowers, trees, plants and birds are also common elements of mon designs.[9]

Mon also add formality to a kimono. A kimono may have one, three or five mon. The mon themselves can be either formal or informal, depending on the formality of the kimono, with formality ranging from the most formal 'full sun' (hinata) crests to the least formal 'shadow' (kage) crests. Very formal kimono display more mon, frequently in a manner that makes them more conspicuous; the most formal kimono display mon on both sides of the chest, on the back of each sleeve, and in the middle of the back. On the armor of a warrior, it might be found on the kabuto (helmet), on the do (breast plate), and on flags and various other places. Mon also adorned coffers, tents, fans and other items of importance.

As in the past, modern mon are not regulated by law, with the exception of the Imperial Chrysanthemum, which doubles as the national emblem, and the paulownia, which is the mon of the office of prime minister and also serves as the emblem of the cabinet and government (see national seals of Japan for further information). Some local governments and associations may use a mon as their logo or trademark, thus enjoying its traditional protection, but otherwise mon are not recognized by law. One of the best known examples of a mon serving as a corporate logo is that of Mitsubishi, a name meaning 'three lozenges' (occasionally translated as 'three buffalo nuts'), which are represented as rhombuses.[10] Another example of corporate use is the logo for the famous soy sauce maker Kikkoman, which uses the family mon of the founder,[11] and finally, the logo of music instrument/equipment and motorcycle builder Yamaha, which shows three tuning forks interlocked into the shape of a capital 'Y' in reference to both their name and the origin of the company.[12]

In Western heraldry

[edit]Japanese mon are sometimes used as charges or crests in Western heraldry. They are blazoned in traditional heraldic style rather than in the Japanese style. Examples include the swastika with arrows used by Japanese ambassador Hasekura Tsunenaga, the Canadian-granted arms of the Japanese-Canadian politician David Tsubouchi,[13] and Akihito's arms as a Knight of the Garter.[14]

-

The swastika with arrows used by the 17th-century Japanese ambassador Hasekura Tsunenaga

Gallery of representative kamon by theme

[edit]Animal motif

[edit]-

Crane crest of Mori clan (similar to Japan Airlines)

-

Triple crane crest

-

Flowers in a turtle's shell

-

Maruni chigai takanoha, the crossing pair of hawk feathers in circle

-

Mythical three-legged crow yatagarasu

-

Quintuple chidori bird crest

-

Kotobuki ebi lobster emblem

Floral motif

[edit]-

Sagari fuji (Wisteria)

-

Daki myōga (Japanese ginger)

-

Sumikirikakuni hanakaku

-

Tachi omodaka or upright threeleaf arrowhead (sagittaria trifolia)

-

Triple pine tree (maruni hidari sangaimatsu) of the Hira clan, member of Taira clan (Heike)

-

Mitsugumi tachibana (triple mandarin orange)

-

Sparrows and bamboo (take ni suzume) of the Date clan

Nature motifs

[edit]-

Yatsuashi hiashi mon of the Kikuchi clan (eight sun-rays)

-

Kuyō mon, representing the sun, moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and two imaginary stars

-

Tsuki ni hoshi (moon and star)

-

Kokumochiji-nuki Hidari-mitsudomoe (thunderbolt)

Tool and pattern motif

[edit]-

6 coin crest of Sanada clan

-

Tang dynasty-style hand fan crest

-

Gion mamori shield motif. The motif is an amulet distributed by Yasaka Shrine to worship Gozu Tennō.

-

Nakagawake kurusu (the cross of Nakagawa clan). The official mon of the Nakagawa clan is the oak, but this is another mon. It is hypothesized that it is patterned after the Christian cross.

-

Three cooking pot hooks

-

Maruni sumitate yotsumei, circle and four eyelets on the edge of the Uda Genji

-

Yamabishi, the crest of the Yamaguchi-gumi yakuza clan. The motif is based on the kanji for yama (山, mountain).

Building and vehicle motifs

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ 日本の家紋大全 梧桐書院 ISBN 434003102X

- ^ Some 6939 mon are listed here Archived 2016-10-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d e ""Kamon": Japan's Family Crests". nippon.com. 10 February 2023. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "News By Louis Vuitton: EXHIBITION IN TOKYO: INSPIRATIONAL JAPAN". Louis Vuitton. 13 December 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Orient Express: A Journey Through Tokyo with Louis Vuitton's Travel Exhibition". Tatler. 16 May 2016. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Japan and Louis Vuitton – The "Volez, Voguez, Voyagez – Louis Vuitton" Exhibition". Waseda University. 14 July 2016. Archived from the original on 17 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ a b c 家紋: 庶民の家にまで普及した紋章 (in Japanese). nippon.com. 10 January 2023. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ 藤紋(ふじ)について (in Japanese). Kamon no iroha. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Nakano, Mas. "Family Crests - Mon". Japan-Society.org. Japan Society of San Diego and Tijuana. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ "The Mitsubishi Mark" Archived 2019-05-06 at the Wayback Machine. Mitsubishi.com. 2008. Accessed 10 August 2008.

- ^ "My family's kamon and history". Archived from the original on 2012-12-14. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ "Yamaha's logo". Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2014-11-19.

- ^ "David Hiroshi Tsubouchi, Public Register of Arms, Flags, and Badges of Canada". Archived from the original on 2022-03-12. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ Coat of arms of Heisi Tenno Archived 2018-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, numericana

![Nakagawake kurusu (the cross of Nakagawa clan [ja]). The official mon of the Nakagawa clan is the oak, but this is another mon. It is hypothesized that it is patterned after the Christian cross.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e3/Japense_crest_Nakagawake_kurusu.svg/120px-Japense_crest_Nakagawake_kurusu.svg.png)