Monitor National Marine Sanctuary

| Monitor National Marine Sanctuary | |

|---|---|

Monitor National Marine Sanctuary | |

| |

| Location | Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, United States |

| Coordinates | 35°00′07″N 75°24′23″W / 35.00195°N 75.40633°W[1] |

| Area | .785 square nautical miles (2.69 km2) |

| Established | February 5, 1975 |

| Governing body | NOAA National Ocean Service |

| monitor | |

Monitor National Marine Sanctuary is the site of the wreck of the USS Monitor, one of the most famous shipwrecks in U.S. history. It was designated as the country's first national marine sanctuary on February 5, 1975,[2] and is one of only two of the seventeen[3] national marine sanctuaries created to protect a cultural resource rather than a natural resource. The sanctuary comprises a column of water 1 nautical mile (1.2 mi; 1.9 km) in diameter extending from the ocean’s surface to the seabed around the wreck of the American Civil War ironclad warship, which lies 16 nautical miles (18 mi; 30 km) south-southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Average water depth in the sanctuary is 230 feet (70 m). Since it sank in 1862, Monitor has become an artificial reef attracting numerous fish species, including amberjack, black sea bass, oyster toadfish, and great barracuda.

USS Monitor

[edit]

Monitor was the prototype for a class of American Civil War ironclad, turreted] warships — known as monitors — that significantly altered both naval technology and marine architecture in the nineteenth century. Designed by the Swedish engineer John Ericsson, the vessel contained all of the emerging innovations that revolutionized warfare at sea. Monitor was constructed in a mere 110 days.[4]

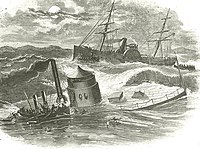

While the design of Monitor was well suited for river combat, her low freeboard and heavy turret made her highly unseaworthy in rough waters. This feature probably led to the early loss of Monitor, which foundered during a heavy storm. Swamped by high waves while under tow by the sidewheel paddle steamer USS Rhode Island, she sank on December 31, 1862, in the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Hatteras. Sixteen of her 62 crewmen were lost in the storm.

Discovery of wreck

[edit]

In 1973, the wreck of Monitor was located on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean by an interdisciplinary team of scientists from Duke University’s Marine Laboratory.[5] The discovery was preceded by extensive historical research and the selection of probable areas where Monitor sank. The search team located what they believed to be the wreck ofMonitor using side-scan sonar and remotely operated cameras. In 1974, the United States Navy and the National Geographic Society launched a second expedition that confirmed the identity of Monitor and produced detailed photographic documentation of the wreck site. The next year, on February 5, 1975, the site was designated as the nation’s first national marine sanctuary.[5] In 1986, Monitor was designated a National Historic Landmark.[citation needed]

Preservation

[edit]

Initial dives in the 1970s and later research expeditions in the early 1990s have indicated that Monitor’s iron hull, having been inundated with salt water for about 130 years, was deteriorating at an accelerated rate. In 1998, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) developed a plan to recover significant "iconic" sections of the wreck for conservation and public display. Additionally, NOAA developed a plan to help stabilize the wreck to reduce or stop further deterioration.[5][6]

The warship's propeller was raised to the surface in 1998. On July 16, 2001, divers from the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary and U.S. Navy divers brought the 30-metric-ton (30-long-ton; 33-short-ton) steam engine to the surface . Due to the depth of the wreck, the divers used surface-supplied diving techniques while breathing heliox.[7] In 2002, after 41 days of work, the revolutionary revolving gun turret was recovered by NOAA and a team of U.S. Navy divers. Before removing the turret, divers discovered the remains of two trapped crew members. The remains of these sailors were transported to the Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command at Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii, for identification.[citation needed]

Many artifacts from Monitor, including her turret, propeller, anchor, stam engine, delicate glass bottles, lumps of coal, wood paneling, a leather book cover, and even walnut halves, have been conserved and are on display at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News, Virginia. Once conservation is complete, artifacts become available for exhibition and study. While the majority of the Monitor artifacts remain at The Mariners’ Museum, other facilities including the Richmond National Battlefield Park in Virginia, the Civil War Naval Museum in Columbus, Georgia, Nauticus in Norfolk, Virginia, and the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras, North Carolina, also display artifacts from the ship.

The wreck of Monitor is one of only three accessible monitor wrecks in the world, the others being the Royal Australian Navy breastwork monitor HMVS Cerberus, which lies at a depth of 10 feet (3 m) in Half Moon Bay on the coast of Victoria, Australia, and the Royal Norwegian Navy KNM Thor, which lies at about 25 feet (8 m) off Verdens Ende in Vestfold county, Norway.

References

[edit]- ^ "Ship Stats". NOAA.

- ^ "Sanctuary Designations & Expansions". NOAA. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ "Sanctuary Map | Monitor National Marine Sanctuary". monitor.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- ^ Yoch, Michael. "NPR - Radio Expeditions: Monitor National Marine Sanctuary". www.npr.org. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Dinsmore, David A; Broadwater, John D (1999). "1998 NOAA Research Expedition to the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary". In Hamilton RW; Pence DF; Kesling DE (eds.). Assessment and Feasibility of Technical Diving Operations for Scientific Exploration. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ^ Administration, US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric. "National Marine Sanctuaries". sanctuaries.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Southerland DG, Davidson DL (2002-10-29). "Electronic diving data collection during Monitor expedition 2001". Oceans 2002. Vol. 2. pp. 908–912. doi:10.1109/OCEANS.2002.1192089. ISBN 978-0-7803-7534-5. S2CID 107060334. Retrieved 2011-01-08.