Anarky

| Anarky | |

|---|---|

Promotional art for Anarky, vol. 2, #1 (May 1999) by Norm Breyfogle. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

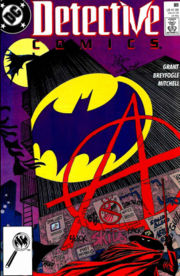

| First appearance | Detective Comics #608 (November 1989) |

| Created by | Alan Grant (writer) Norm Breyfogle (artist) |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Lonnie Machin |

| Species | Human |

| Partnerships | Legs |

| Notable aliases | Moneyspider |

| Abilities |

|

Anarky is an anti hero appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. Co-created by Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle, he first appeared in Detective Comics #608 (November 1989), as an adversary of Batman. Anarky is introduced as Lonnie Machin, a child prodigy with knowledge of radical philosophy and driven to overthrow governments to improve social conditions. Stories revolving around Anarky often focus on political and philosophical themes. The character, who is named after the philosophy of anarchism, primarily espouses anti-statism and attacks capitalism; however, multiple social issues have been addressed through the character, including environmentalism, antimilitarism, economic inequality, and political corruption. Inspired by multiple sources, early stories featuring the character often included homages to political and philosophical texts, and referenced anarchist philosophers and theorists. The inspiration for the creation of the character and its early development was based in Grant's personal interest in anti-authoritarian philosophy and politics.[1] However, when Grant himself transitioned to the philosophy of Neo-Tech developed by Frank R. Wallace, he shifted the focus of Anarky from a vehicle for social anarchism and then libertarian socialism, with an emphasis on wealth redistribution and critique of Capitalism, to themes of individualism and personal reflections on the nature of consciousness.[2]

Originally intended to only be used in the debut story in which he appeared, Grant decided to continue using Anarky as a sporadically recurring character throughout the early 1990s, following positive reception by readers and Dennis O'Neil.[3] The character experienced a brief surge in media exposure during the late 1990s when Breyfogle convinced Grant to produce a limited series based on the character. The 1997 spin-off series, Anarky, was received with positive reviews and sales, and later declared by Grant to be among his "career highlights".[4] Batman: Anarky, a trade paperback collection of stories featuring the character, soon followed. This popular acclaim culminated, however, in a financially and critically unsuccessful ongoing solo series. The 1999 Anarky series, for which even Grant has expressed his distaste, was quickly canceled after eight issues.[1][5]

Following the cancellation of the Anarky series, and Grant's departure from DC Comics, Anarky experienced a prolonged period of absence from DC publications, despite professional and fan interest in his return.[6][7] This period of obscurity lasted approximately nine years, with three brief interruptions for minor cameo appearances in 2000, 2001, and 2005. In 2008, Anarky reappeared in an issue of Robin authored by Fabian Nicieza, with the intention of ending this period of obscurity.[8][9][10] The storyline drastically altered the character's presentation, prompting a series of responses by Nicieza to concerned readers.[11][12] Anarky became a recurring character in issues of Red Robin, authored by Nicieza, until the series was cancelled in 2011 in the aftermath of The New 52.[13] A new Anarky was introduced into the New 52 continuity in October 2013, in an issue of Green Lantern Corps, which itself was a tie-in to the "Batman: Zero Year" storyline.[14] Yet more characters have been authored as using the Anarky alias in the New 52 continuity via the pages of Detective Comics[15][16] and Earth 2: Society.[17]

From 2013, Anarky began to be featured more heavily in media adaptations of DC Comics properties, across multiple platforms.[18] In July, a revamped version of Anarky was debuted as the primary antagonist in Beware the Batman, a Batman animated series produced by Warner Bros. Animation.[19][20] In October, the character made his video game debut in Batman: Arkham Origins, as a villain who threatens government and corporate institutions with destruction.[21] Anarky made his live action debut in the Arrowverse television series Arrow in the fourth and fifth seasons, portrayed by Alexander Calvert, once again as a villain.[22]

Publication history

[edit]Creation and debut

[edit]

Originally inspired by his personal political leanings, Alan Grant entertained the idea of interjecting anarchist philosophy into Batman comic books. In an attempt to emulate the success of Chopper, a rebellious youth in Judge Dredd, he conceptualized a character as a 12-year-old anarchist vigilante, who readers would sympathize with despite his harsh methods;[24] additionally, in the wake of the death of Jason Todd, Grant hoped that Anarky could be used as the new Robin.[25] Creating the character without any consultation from his partner, illustrator Norm Breyfogle,[26] his only instructions to Breyfogle were that Anarky be designed as a cross between V and the black spy from Mad magazine's Spy vs. Spy.[3] The character was also intended to wear a costume that disguised his youth, and so was fitted with a crude "head extender" that elongated his neck, creating a jarring appearance. This was in fact intended as a ruse on the part of writer Alan Grant to disguise the character's true identity, and to confuse the reader into believing Anarky to be an adult.[27] While both of these design elements have since been dropped, more enduring aspects of the character have been his golden face mask, "priestly" hat, and his golden cane.[28]

The first Anarky story, "Anarky in Gotham City, Part 1: Letters to the Editor", appeared in Detective Comics #608, in November 1989. Lonnie Machin is introduced as "Anarky" as early as his first appearance in Detective Comics #608, withholding his origin story for a later point. He is established as an uncommonly philosophical and intelligent 12-year-old.[29] Lonnie Machin made his debut as "Anarky" by responding to complaints in the newspaper by attacking the offending sources, such as the owner of a factory whose byproduct waste is polluting local river water.[29] Anarky and Batman ultimately come to blows, and during their brief fight, Batman deduces that Anarky is actually a young child. During this first confrontation, Anarky is aided by a band of homeless men, including Legs, a homeless cripple who becomes loyal to him and would assist him in later appearances. After being caught, Lonnie is locked away in a juvenile detention center.[30]

Anarky series

[edit]"Anarky, not having any super powers, doesn't have what it takes to bring the fans in month after month. He's the sort of character you can get away with using in an annual once a year plus his own miniseries once a year and maybe as a guest star every couple of years, but he's not capable, he's not strong enough to hold his own monthly title. Very few characters are when it comes down to it".

—Alan Grant, 2007.[1]

Following the comic book industry crash of 1996, Norm Breyfogle sought new employment at DC Comics. Darren Vincenzo, then an editorial assistant at the company, suggested multiple projects which Breyfogle could take part in. Among his suggestions was an Anarky limited series, to be written by Grant or another specified author. Following encouragement from Breyfogle, Grant agreed to participate in the project.[31] The four-issue limited series, Anarky, was published in May 1997. Entitled "Metamorphosis", the story maintained the character's anti-authoritarian sentiments, but was instead based on Neo-Tech, a philosophy based on Objectivism, developed by Frank R. Wallace.[2]

Well received by critics and financially successful, Grant has referred to the limited series as one of his favorite projects, and ranked it among his "career highlights".[4] With its success, Vincenzo suggested continuing the book as an ongoing series to Breyfogle and Grant. Although Grant was concerned that such a series would not be viable, he agreed to write it at Breyfogle's insistence, as the illustrator was still struggling for employment.[31] Building on the increasing exposure of the series, a trade paperback featuring the character titled Batman: Anarky was published. However, Grant's doubts concerning the ongoing series's prospects eventually proved correct. The second series was panned by critics, failed to catch on among readers, and was canceled after eight issues, but Grant has noted that it was popular in Latin American countries, supposing this was due to a history of political repression in the region.[3][32]

Absence from DC publications

[edit]"We don't have any conclusive evidence, but Alan and I can't help but feel that Anarky's philosophy grated on somebody's nerves; somebody got a look at it and didn't like it [...] So I've generally gotten the impression that Anarky was nixed because of its philosophy. Especially in this age of post 9/11, Anarky would be a challenge to established authority. He's very anti-establishment, that's why he's named Anarky!"

—Norm Breyfogle, 2003.[6]

After the financial failure of Anarky vol. 2, the character entered a period of absence from DC publications that lasted several years. Norm Breyfogle attempted to continue using the character in other comics during this time. When his efforts were rejected, he came to suspect the character's prolonged absence was due in part to censorship.[6] Since the cancellation of the Anarky series, Grant has disassociated himself from the direction of the character, simply stating, "you have to let these things go."[5]

In 2005, James Peaty succeeded in temporarily returning Anarky to publication, writing Green Arrow #51, Anarky in the USA. Although the front cover of the issue advertised the comic as the "return" of the character, Anarky failed to make any further appearances.[33] This was despite comments by Peaty that he had further plans to write stories for the character.[34]

Anarky retained interest among a cult fan base during this obscure period.[31] During a panel at WonderCon 2006, multiple requests were made by the audience for Anarky to appear in DC Comics’ limited series, 52. In response, editors and writers of 52 indicated Anarky would be included in the series, but the series concluded without Anarky making an appearance, and with no explanation given by anyone involved in the production of the series for the failed appearance.[I]

Return as "Moneyspider"

[edit]"I took 2 characters who had not been seen in 10 years and told a story with them that sets up the potential for more stories to be told using those characters. I call that a good day at the office."

—Fabian Nicieza, 2009.[12]

Anarky reappeared in the December issue of Robin, #181.[8] With the publication of Robin #181, "Search For a Hero, Part 5: Pushing Buttons, Pulling Strings", on December 17, 2008, it was revealed that Lonnie Machin's role as Anarky had been supplanted by another Batman villain, Ulysses Armstrong. Fabian Nicieza, author of the issue and storyline in which Anarky appeared, depicted the character as being held hostage by Armstrong, "paralyzed and catatonic",[11] encased in an iron lung, and connected to computers through his brain. This final feature allowed the character to connect to the internet and communicate with others via a speech synthesizer.[35] Nicieza's decision to give Machin's mantle as Anarky to another character was due to his desire to establish him as a nemesis for Tim Drake, while respecting the original characterization of Anarky, who Nicieza recognized as neither immature, nor a villain. Regardless, Nicieza did desire to use Machin and properly return the character to publication, and so favored presenting Ulysses H. Armstrong as Anarky, and Lonnie Machin as Moneyspider, a reference to a secondary name briefly used by Grant for Anarky in storyline published in 1990.[II]

The reactions to Robin #181 included negative commentary from political commentator and scholar, Roderick Long,[36] and Alan Grant himself.[37] Among fans who interacted with Nicieza in a forum discussion, some responses were also negative, prompting responses from Nicieza in his own defense.[11][12]

With the conclusion of Robin, Nicieza began authoring the 2009 Azrael series, leaving any future use of Anarky or Moneyspider to author Christopher Yost, who would pick up the Robin character in a new Red Robin series. In the ensuing months, Yost only made one brief reference to Anarky, without directly involving the character in a story plot.[38] In April 2010, Nicieza replaced Yost as the author of Red Robin, and Nicieza was quick to note his interest in using Anarky and Moneyspider in future issues of the series.[39] Nicieza reintroduced Ulysses Armstrong and Lonnie Machin within his first storyline, beginning in Red Robin #16, "The Hit List", in December 2010.[40] Nicieza then proceeded to regularly use Lonnie as a cast member of the ongoing Red Robin series, until its cancellation in October 2011. The series was concluded as a result of The New 52, a revamp and relaunch by DC Comics of its entire line of ongoing monthly superhero books, in which all of its existing titles were cancelled. 52 new series debuted in September 2011 with new #1 issues to replace the cancelled titles.[13]

The New 52

[edit]While Anarky was "rising in profile in other media" by mid-2013, the character had yet to be reintroduced to the status quo of the Post-New 52 DC Universe.[41] This changed on August 12, when DC Comics announced that Anarky would be reintroduced in Green Lantern Corps #25, "Powers That Be", on November 13. The issue was a tie-in to the "Batman: Zero Year" crossover event, authored by Van Jensen and co-plotted by Robert Venditti.[42]

In the lead up to the publication date, at a panel event at the New York Comic Con, Jensen was asked by a fan holding a "plush Anarky doll" what the character's role would be in the story. Jensen explained that Anarky "would have a very big hand" in the story, and further explained, "you can understand what he's doing even if you don't agree with what he's doing".[43] Jensen had also indicated that his version of Anarky would be a "fresh take that also honors his legacy".[44] The story featured a character study of John Stewart, narrating Stewart's final mission as a young Marine in the midst of a Gotham City power blackout and citywide evacuation, mere days before a major storm is to hit the city. Anarky is depicted as rallying a group of followers and evacuees to occupy a sports stadium, on the basis that the area the stadium was built upon was gentrified at the expense of the local community and should be returned to them.[14] The storyline brought two particular additions to the revamped version of Anarky; the first being that this new version of Anarky is portrayed as an African American; the second being to preserve the character's anonymity, as Anarky escapes custody at the end of the story without an identity behind the mask being revealed.[45]

Another version of Anarky debuted in the post-New 52 Detective Comics series, written by Francis Manapul and Brian Buccellato.[15][16] This character is not the same Anarky that appeared in "Batman: Zero Year", but rather a corrupt politician named Sam Young who used the Anarky persona to exact revenge on the Mad Hatter for murdering his sister.[46]

A female version of Anarky from the alternate reality of Earth-Two was introduced in Earth 2: Society's 2015 story line, "Godhood", by Daniel H. Wilson. Prior to the fictional events of the series, this Anarky detonated a bomb in the city of Neotropolis that resulted in a public riot. She disappears before Superman and Power Girl can apprehend her. In the series, she is portrayed as a hacker that is allied with such characters as Doctor Impossible, the Hourman, and Johnny Sorrow.[17]

DC Rebirth

[edit]Teased as a "very unlikely ally",[47] Anarky appears for the first time in DC Rebirth in May 2017. Revealed in Detective Comics #957 (May 2016), a redesigned Anarky offers to help Spoiler in her new quest against vigilantism in Gotham.[48] In 2018 the character was featured in the one-shot issue Red Hood vs. Anarky, here pitted against the former Robin Jason Todd. Writer Tim Seeley expressed that he decided to pair up the Red Hood and Anarky because he feels that they were similar characters: "To me, what made that [pairing] interesting is that Red Hood is the bad seed of the family, to some degree. And I can play that against Anarky, who in some ways, could be a fallen member of the Bat family. The way that James [Tynion] played Anarky in Detective Comics is he shared a lot of the same goals and motivations with the [Gotham Knights] team, but he's also a guy who has a tendency to run afoul of Batman's beliefs".[49]

Characterization

[edit]

Anarky has undergone several shifts in his characterization over the course of the character's existence. These were largely decided upon by Alan Grant, who between the creation of Anarky to the end of the 1999 Anarky series, was largely the sole author of the character. After the departure of Grant and Breyfogle from DC Comics, Anarky's characterization fell to various authors who utilized him thereafter.

Description and motivations

[edit]Lonnie Machin is introduced as a twelve-year-old school boy. An only child, he shares his physical traits of light skin and red hair with both of his parents, Mike and Roxanne Machin, a middle-class family living in Gotham City.[29] The character's age was continuously adjusted over the course of several years; stated to be fourteen during "The Anarky Ultimatum" in Robin Annual #1,[50] it is reestablished as fifteen during the events of the Anarky limited series,[51] and adjusted as 16 the following year during the ongoing series.[52]

Grant laconically described Lonnie Machin as "a serious-beyond-his-years teenager who wants to set the world to rights".[53] As the character was based on a theme of ideas, he had initially been given no personal, tragic past, a common motivator in superhero fiction. This was intended to contrast with Batman, who fought crime due to personal tragedy, while Anarky would do so in the name of ideals and beliefs.[24] As the character was further developed, he was also intended to contrast with common teenage superheroes. Referring to the tradition established by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby of saddling teenagers with personal problems, Grant purposely gave Anarky none, nor did he develop a girlfriend or social life for the character. As Grant wrote for the Batman: Anarky introduction, this was intended to convey the idea that Anarky was single-minded in his goals.[24] In one of the earliest explorations of Lonnie Machin's back story in "The Anarky Ultimatum", Grant described Lonnie as a voracious reader, but also of being isolated from peers his own age during his childhood.[50] This was elaborated upon years later in the "Anarky" storyline, which described Lonnie as having lost a childhood friend living in an impoverished nation, the latter suffering the loss of his family due to civil war and strife before disappearing entirely. The resulting shock of discovering at such a young age that the world was in turmoil precipitated Lonnie Machin's rapid maturation and eventual radicalization.[54]

Heroic and villainous themes

[edit]Anarky's introduction during the late 1980s was part of a larger shift among supervillains in the Batman franchise of the time. While many naive and goofy villains of previous eras were abandoned, and more iconic villains made more violent to cater to tastes of a maturing readership, some were introduced to challenge readers to "question the whole bad/good guy divide". Falling into "the stereotype anarchist bomb-toting image", Anarky's design was countered by his principled stances to create an odd contrast.[55] In a review of the Anarky miniseries, Anarky was dubbed an "anti-villain", as opposed to "antihero", due to his highly principled philosophy, which runs counter to most villains: "In the age of the anti-hero, it only makes sense to have the occasional anti-villain as well. But unlike sociopathic vigilante anti-heroes like the Punisher, an anti-villain like Anarky provides some interesting food for thought. Sure, he breaks the law, but what he really wants is to save the world ... and maybe he's right".[56]

Breyfogle's characterization of Anarky has shifted on occasion, with him at times referring to Anarky as a villain, and at other times as a hero. In his 1998 introductory essay composed for Batman: Anarky, Breyfogle characterized Anarky as not being a villain, but rather a "misunderstood hero", and continued that "he's a philosophical action hero, an Aristotle in tights, rising above mere 'crime-fighter' status into the realm of incisive social commentary".[28] A year later, Breyfogle conceded that Anarky was "technically" a villain, but insisted "I don't consider him a villain ..."[27] Breyfogle later reconsidered the character in more ambiguous terms for a 2005 interview: "Anarky isn't a villain, he's his own character. He's definitely not a superhero, although it depends on who you talk to".[57]

"Anarky's world clashes as much with the traditional world of superheroes as it does with the world of crime. So the interplay between him and Green Lantern and him and Superman is not the usual kind of hero interplay".

—Alan Grant, 1998.[58]

Grant has been more direct in his description of Anarky's virtuous attributes: "In my eyes, Anarky's a hero. Anarky's the hero I want to be if I was smart enough and physically fit enough". Acknowledging that Anarky's moral perspective was guided by his own, Grant expressed that the conflict between Anarky and other heroes is a result of their political divisions: "In my eyes, he's a hero, but to others, they see him as a villain. That is because most people might gripe about the political situation, or various aspects of the political situation, and wouldn't advocate the total overthrow of the system under which we live. Anarky certainly does that, and more".[58]

In creating stories involving Anarky, other writers have played off this anti-heroic and anti-villainous tension. James Peaty made the heroic and political comparisons between Lonnie Machin and Oliver Queen the central theme of his 2005 Green Arrow story, "Anarky in the USA": "Anarky comes to find Ollie because of his reputation and is quite disappointed in Ollie's reaction towards him. However, as the story unfolds, Ollie has to re-assess his initial reaction to Anarky and his own much vaunted 'radical' credentials". [34] With his controversial revival of the character in 2008, Fabian Nicieza chose to portray the mantle of Anarky as being possessed by a villain other than Lonnie Machin on the grounds that Lonnie was too heroic to act out the part of a black hat: "Since Lonnie is too smart to be immature and NOT a 'villain', I wanted Anarky, but it couldn't be Lonnie without compromising who he is as a character".[11]

"So, one of the reasons I really like Anarky is he's a kind of classic anti-villain, right? Like, he's trying to do the right thing; he believes he's doing the right thing; from Batman's perspective he's not; but from a dramatic perspective, if you look at him, there's a really good argument to be made for what he does and why he does it".

—Eric Holmes, 2013.[59]

In the character's 2013 video game debut in Batman: Arkham Origins, creative director Eric Holmes dubbed Anarky a "classic anti-villain".[59] A "social activist" who wishes to "liberate and free people", Anarky views himself as a hero akin to Batman and offers an alliance with him, but his approach is rebuked on the basis that their methods are nothing alike.[60] Nonetheless, he attracts a following among the city's downtrodden and particularly the homeless, whom he protects from the hostility of police officers.[41] This "special relationship" between the homeless who look up to a villain, who in turn acts as their protector against police who prey upon them, was intended to present an area of grey morality for the player to consider.[59]

On two occasions Grant nearly went against Dennis O'Neil's early wish that Anarky not kill opponents. These events include his appearance during the Batman: Knightfall saga, in which Grant briefly portrayed Anarky as preparing to kill both the Scarecrow and Batman-Azrael.[61] Grant also implied Anarky was a lethal figure in "The Last Batman Story", part of Armageddon 2001 crossover event. In the story, a time traveler shows Batman a possible future in the (relatively) not-too-distant year of 2001. An aged Batman is framed and sentenced to death for murder, but Anarky, now an adult, sympathizes with the fallen hero and breaks into the prison in an attempt to rescue Batman. The latter resists his help, on the basis that Anarky has killed others in the past, and the two never reconciled their differences.[62]

Grant later expressed relief that he had not fully committed to portraying Anarky as a potential murderer, as he felt "Anarky would have compromised his own beliefs if he had taken the route of the criminal-killer".[24] Anarky was given a non-lethal approach in The Batman Adventures #31, "Anarky", written by Alan Grant, who acted as a guest author for the issue. Anarky takes business elites hostage and places them on public trial, broadcast from a pirate television show. He charges these men with such crimes as the creation of land mines that kill or cripple thousands, funding Third World dictators, polluting the air with toxic chemicals, and profiting from wage slavery, and threatens each man with a bomb if the public should find them guilty. When the explosions take place, it is revealed that the bombs are fake, and the public trials were only intended to expose the men and raise public awareness. One bomb explosion carried a specific message. It unfurled a banner that denounced lethal weapons.[63]

Contradicting Anarky's non-lethal portrayal, entries for the character in Who's Who in the DC Universe,[64] The DC Comics Encyclopedia,[65] and The Supervillain Book,[66] have falsely referred to Anarky as having killed criminals in early appearances. Norm Breyfogle was also under the false impression that Anarky had killed for several years, having failed to realize the original script for Anarky's debut storyline had been rewritten. Grant eventually explained the situation to Breyfogle in 2006, during a joint interview.[1] Despite this regular equivocation of Anarky with murder and villainy in DC Comics character guides, the company made efforts to describe the character in heroic terms in promoting the 1999 Anarky series. During this time, DC Comics described Anarky as an "anti-establishment loose cannon trying to do good as a hero to the disenfranchised".[67]

Political and philosophical themes

[edit]"(Anarky is) a philosophical action hero, an Aristotle in tights, rising above mere "crime-fighter" status into the realm of incisive social commentary. In fact, Anarky exists primarily to challenge the status quo of hierarchical power, and he may be the first mainstream comics hero of his type to do it consistently and with such rational intelligence".

—Norm Breyfogle, 1998.[28]

In the initial years following Anarky's creation, Grant rarely incorporated the character into Batman stories, being reserved for stories in which the author wished to make a philosophical point.[24] Originally, Grant created Anarky as an anarchist with socialist and populist leanings. In this early incarnation, Anarky was designed as an avatar for Grant's personal meditations on political philosophy, and specifically for his burgeoning sympathy for anarchism.[1]

Within the books, the nature of the character's political opinions were often expressed through the character's rhetoric, and by heavy use of the circle-A as a character gimmick. The character's tools often incorporate the circle-A motif into them. In his earliest incarnation, he would also use red spray-paint to leave the circle-A as a calling card at crime scenes.[29] The circle-A has also been used to decorate the character's base of operations, either as graffiti or suspended from wall tapestries.[35][50][68]

In some instances, Anarky's political behavior would stand as the only political element of the story,[50][69] while in other instances, entire stories would be framed to create a political parable. In Batman: Shadow of the Bat Annual #2, an Elseworlds story entitled "The Tyrant", Grant made dictatorship and the corrupting influence of power the primary theme. Batman (under the influence of Jonathan Crane) uses his resources to usurp power in the city of Gotham and institute a police state in which he exercises hegemonic control over the city's population. Anarky becomes a resistance leader, undermining the centers of Batman's power and ultimately overthrowing Bruce Wayne's tyranny.[70] The story ends with a quote by Mikhail Bakunin: "(For reasons of the state) black becomes white and white becomes black, the horrible becomes humane and the most dastardly felonies and atrocious crimes become meritorious acts".[71] During the early years of the character's development, virtually no writers other than Grant used Anarky in DC publications. In the singular portrayal by an author other than Grant during this period, writer Kevin Dooley used Anarky in an issue of Green Arrow, producing an explicitly anti-firearm themed story. Throughout the narrative, dialogue between Anarky and Green Arrow conveys the need for direct action, as Anarky attempts to persuade Oliver Queen to sympathize with militant, economic sabotage in pursuit of social justice.[72]

Literary cues illustrated into scenes were occasionally used whenever Anarky was a featured character in a comic. During the Anarky limited series, fluttering newspapers were used to bear headlines alluding to social problems.[73][74] Occasionally, the titles of books found in Anarky's room would express the character's philosophical, political, or generally esoteric agenda. In both Detective Comics #620 and Batman: Shadow of the Bat #40, a copy of V for Vendetta can be seen on Lonnie Machin's bookshelf as homage.[69][75] Other books in his room at different times have included Apostles of Revolution by Max Nomad, The Anarchists by James Joll, books labeled "Proudhon" and "Bakunin", and an issue of Black Flag.[75] Non-anarchist material included books labeled "Plato", "Aristotle", and "Swedenborg",[69] and a copy of Synergetics, by Buckminster Fuller.[76] The character also made references to Universe by Scudder Klyce, an extremely rare book.[30][54] When asked if he was concerned readers would be unable to follow some of the more obscure literary references, Grant explained that he hadn't expected many to do so, but reported encountering some who had, and that one particular reader of the 1999 Anarky series had carried out an ongoing correspondence with him on the topic as of 2005.[3]

"Although I haven't read them in chronological order I would think it would be quite easy to see the parallel between Anarky's thought processes and my own thought processes".

—Alan Grant, 1997.[2]

Over the course of several years, Grant's political opinions shifted from social anarchism to libertarian socialism and then to precepts associated with Objectivism. Grant later speculated that this transformation would be detectable within stories he'd written. By 1997, Grant's philosophy settled on Neo-Tech, which was developed by Frank R. Wallace, and when given the opportunity to write an Anarky miniseries, he decided to redesign the character accordingly. Grant laid out his reasoning in an interview just before the first issue's publication: "I felt he was the perfect character" to express Neo-Tech philosophy, because he's human, he has no special powers, the only power he's got is the power of his own rational consciousness".[2] This new characterization was continued in the 1999 Anarky ongoing series.

The limited and ongoing series were both heavily influenced by Neo-Tech, despite the term never appearing in a single issue. New emphasis was placed on previously unexplored themes, such as the depiction of Anarky as an atheist and a rationalist.[77] Grant also expressed a desire to use the comic as a vehicle for his thoughts concerning the mind and consciousness,[5] and made bicameral mentality a major theme of both series.[78] While this trend led the character away from the philosophies he had espoused previously, the primary theme of the character remained anti-statism. In one issue of the 1999 series, a character asked what the nature of Anarky's politics were. The response was that Anarky was neither right-wing, nor left-wing, and that he "transcends the political divide".[79] Grant has specified that he categorized Anarky politically as an anarchist who "tried to put anarchist values into action".[80] Norm Breyfogle also stated in 1999 that the character represented anarchist philosophy,[27] but said in 2003 that he believed the Neo-Tech influence allowed Anarky to be classified as an Objectivist.[6]

Skills, abilities, and resources

[edit]"The audaciousness of a non-super-powered teenager functioning as a highly effective adult without a mentor is pretty iconoclastic in a genre where it sometimes appears 'it's all been done before'".

—Norm Breyfogle, 1998.[28]

Grant developed Anarky as a gadgeteer—a character who relies on inventions and gadgets to compensate for a lack of superpowers—and as a child prodigy. In early incarnations he was portrayed as highly intelligent, but inexperienced. Lacking in many skills, he survived largely by his ingenuity. In accordance with this, he would occasionally quote the maxim, "the essence of anarchy is surprise".[30] By 1991 a profile of the character, following the introduction of Anarky's skills as a hacker in the "Rite of Passage" storyline of Detective Comics #620, described that "Lonnie's inventive genius is equaled only by his computer wizardry".[64]

Anarky's abilities were increased during the character's two eponymous series, being portrayed as having enormous talents in both engineering and computer technology, as well as prodigiously developing skills in martial arts. This was indicated in several comics published just before the Anarky miniseries, and later elaborated upon within the series itself.

Early skills and equipment

[edit]Described as physically frail in comparison to the adults he opposes, the character often utilizes cunning, improvisation, and intelligence as tools for victory. During the Knightfall saga, the character states: "The essence of anarchy is surprise – spontaneous action ... even when it does require a little planning!"[81]

Early descriptions of the character's gadgets focused on low-tech, improvised tools and munitions, such as flare guns,[61] swing lines,[50] throwing stars,[82] small spherical shelled explosives with burning fuses (mimicking round mortar bombs stereotypically associated with 19th-century anarchists),[29] gas-bombs,[29] smoke bombs,[50] and his primary weapon, a powerful electric stun baton shaped as a golden cane.[29]

As a wanted criminal, Anarky's methods and goals were described as leaving him with little logistical support amongst the heroic community, or the public at large, relegating him to underground operation. When in need of assistance, he would call on the help of the homeless community in Gotham who had supported him since his first appearance.[30]

Anarky was described as having developed skills as a computer hacker to steal enormous sums of money from various corporations in his second appearance, part of the "Rite of Passage" storyline in Detective Comics #620.[83] This addition to the character's skill set made him the second major hacker in the DC Universe, being preceded by Barbara Gordon's debut as Oracle,[84] and was quickly adapted by 1992 to allow the character to gain information on other heroes and villains from police computer networks.[50]

Anarky series ability upgrades

[edit]According to Alan Grant, the urgency with which Anarky views his cause has necessitated that the character forsake any social life, and increase his abilities drastically over the years. In his introduction of Batman: Anarky: "The kid's whole life is dedicated to self-improvement, with the sole aim of destroying the parasitic elites who he considers feast off ordinary folks".[24] A review of the first issue of the 1999 series described Anarky as akin to a "Batman Jr." The reviewer continued that "[Grant] writes Lonnie like a teenager who is head and shoulders above the rest of the population, but still a kid".[85]

In 1995, Grant used the two part "Anarky" storyline in Batman: Shadow of the Bat to alter the character's status quo in several ways that would reach their fruition in the first Anarky series. To accomplish this feat, several plot devices were used to increase Lonnie's abilities. To justify the character's financial independence, Anarky was described as using the internet to earn money through his online bookstore, Anarco, which he used as a front company to propagate his philosophy. A second front organization, The Anarkist Foundation, was also developed to offer grants to radical causes he supports.[86] A Biofeedback Learning Enhancer was employed to increase Lonnie's abilities. The cybernetic device was described as being capable of amplifying brain functions by a multiple of ten.[86] Anarky was also described as having begun to train in martial arts, following the character's time in juvenile hall.[87]

The 1997 Anarky limited series saw the earlier plot devices of the preceding "Anarky" storyline become narrative justifications for drastically upgraded skill sets. Anarky's earlier brain augmentation was now described as having "fused" the hemispheres of his brain, in a reference to bicameral mentality. Meanwhile, the character's business enterprises were said to have gained him millions of dollars in the dot-com bubble. The character's combat abilities were described as having progressed remarkably, and to have included training in multiple styles which he "integrated" into a hybrid fighting style.[88][89] Even the character's primary stun baton weapon was enhanced, with a grappling hook incorporated into the walking stick itself to allow dual functionality.[89]

With this enhanced intelligence and financial assets, the 1999 ongoing series narrates that Anarky went on to create an on-board AI computer, MAX (Multi-Augmented X-Program);[52] a crude but fully functioning teleportation device capable of summoning a boom tube,[90] and secretly excavated an underground base below the Washington Monument.[52] Portrayed as an atheist by Grant, Anarky espoused the belief that "science is magic explained", and was shown to use scientific analysis to explain and manipulate esoteric forces of magic and energy.[91] Anarky's skill in software cracking was further increased to allow him to tap into Batman's supercomputer,[89] and the Justice League Watchtower.[52]

This evolution in Anarky's abilities was criticized as having overpowered the character in a Fanzing review of the Anarky ongoing series. The rapid development was seen as preventing the suspension of disbelief in the young character's adventures, which was said to have contributed to the failure of the series.[92] This view stood in contrast with that of Breyfogle, who considered Anarky's heightened skill set to be a complementary feature, and contended that Anarky's advanced abilities lent uniqueness to the character. Breyfogle wrote: "Anarky's singularity is due partly to his being, at his age, nearly as competent as Batman".[28]

Abilities as Moneyspider

[edit]In Fabian Niciza's stories for Red Robin, Lonnie Machin's abilities as Moneyspider were revamped, with the character taking on the persona of an "electronic ghost".[11] Comatose, Moneyspider was free to act through his mind via connections to the internet, and interacted with others via text messaging and a speech synthesizer. In this condition, he acts to "create an international web that will [access] the ins and outs of criminal and corporate operations".[93] Within virtual reality, the character's augmented intelligence was described as a "fused bicameral mind", able to maintain a presence online at all times, while another part of his mind separately interacted with others offline.[94]

Costume

[edit]Designs by Norm Breyfogle

[edit]

Anarky's costume has undergone several phases in design, the first two of which were created by Norm Breyfogle, in accordance with Grant's suggestions. The original costume was composed of a large, flowing red robe, over a matching red jumpsuit. A red, wide brimmed hat baring the circle-A insignia; a golden, metallic face mask; and red hood, completed the outfit. The folds of the robe concealed various weapons and gadgets.[29] Breyfogle later expressed that the color scheme chosen held symbolic purpose. The red robes "represented the blood of all the innocents sacrificed in war". The gold cane, face mask, and circle-A symbol represented purity and spirituality. The connection to spirituality was also emphasized through the hat and loose fabric, which mimicked that of a priest. Breyfogle believed the loose clothes "[went] better with a wide-brimmed hat. It's more of a colloquial style of clothing ..." However, observers have noted that Breyfogle's Christian upbringing may have also inspired the "priestly analogy".[27]

"[Anarky's fake head] was unique and provided a drawing challenge in that the reader should later say, 'So that's why Anarky looked so awkward!' Such awkwardness, in fact, was one reason I eliminated the fake head in the miniseries ...

—Norm Breyfogle, 1998.[28]

This costume was also designed to disguise Anarky's height, and so included a "head extender" under his hood, which elongated his neck. This design was also intended to create a subtle awkwardness that the reader would subconsciously suspect as being fake, until the reveal at the end of Anarky's first appearance. Despite the revelation of this false head, which would no longer serve its intended purpose at misdirecting the reader, the head extender was included in several return appearances, while at irregular times other artists drew the character without the extender.[V] This discontinuity in the character's design ended when Breyfogle finally eliminated this aspect of the character during the 1997 limited series, expressing that the character's height growth had ended its usefulness.[28] In reality, Breyfogle's decision was also as a result of the difficulty the design presented, being "awkward [to draw] in action situations".[27]

"... as an antihero, Anarky doesn't have to be beholden to one fashion statement".

—Vera H-C Chan, 1999.[27]

Anarky's second costume was used during the 1999 ongoing Anarky series. It retained the red jumpsuit, gold mask, and hat, but excised the character's red robes. New additions to the costume included a red cape, a utility belt modeled after Batman's utility belt, and a single, large circle-A across the chest, akin to Superman's iconic "S" shield. The golden mask was also redesigned as a reflective, but flexible material that wrapped around Anarky's head, allowing for the display of facial movement and emotion. This had previously been impossible, as the first mask was made of inflexible metal. Being a relatively new creation, Breyfogle encountered no editorial resistance in the new character design: "Because [Anarky] doesn't have 50 years of merchandising behind him, I can change his costume whenever I want ..."[27] Within the Anarky series, secondary costumes were displayed in Anarky's base of operations. Each was slightly altered in design, but followed the same basic theme of color, jumpsuit, cloak, and hat. These were designed for use in various situations, but only one, a "universal battle suit", was used during the brief series.[52] These suits were also intended to be seen in the unpublished ninth issue of the series.[95]

Post-Breyfogle designs

[edit]| External image | |

|---|---|

In 2005, James Peaty's Green Arrow story, "Anarky in the USA", featured a return to some of the costume elements used prior to the Anarky series. Drawn by Eric Battle, the circle-A chest icon was removed in favor of a loose fabric jumpsuit completed with a flowing cape. The flexible mask was replaced with the previous, unmoving metallic mask, but illustrated with a new reflective quality. This design element was used at times to reflect the face of someone Anarky looked at, creating a mirroring of a person's emotions upon Anarky's own mask.[33] This same effect was later reused in two issues of Red Robin.[97][98] For the usurpation of the "Anarky" mantle by Ulysses Armstrong, Freddie Williams II illustrated a new costume design for Armstrong that featured several different design elements. While retaining the primary colors of gold and red, the traditional hat was replaced with a hood, and a new three-piece cuirass with shoulder guards and leather belt was added. The mask was also altered from an expressionless visage to a menacing grimace.[35] This design was later re-illustrated by Marcus To in the Red Robin series, but with a new color scheme in which red was replaced with black.[40]

Alternative media designs

[edit]| External media | |

|---|---|

| Images | |

| Video | |

In attempting to present the character as a figurative mirror to Batman, the costume worn by Anarky in Beware the Batman was radically redesigned as entirely white, in contrast to Batman's black Batsuit. It consists of a tightly worn jumpsuit, cape, hood, flexible mask with white-eye lenses, and a utility belt. Upon the chest is a small, stylized circle-A in black.[20] The design was negatively compared by reviewers to the longstanding design for Moon Knight, a Marvel Comics superhero.[102][103][104]

The costume redesign for Anarky in Batman: Arkham Origins, while stylized, attempted to thematically highlight the character's anarchist sentiments by updating his appearance utilizing black bloc iconography.[21] Donning a red puffer flight jacket, hoodie and cargo pants, the character sported gold accents decorating his black belt, backpack and combat boots, and completed this with an orange bandana wrapped below his neck. His metallic mask was replaced with a white theatrical stage mask, evocative of the Guy Fawkes mask made popular among protesters by V for Vendetta and Anonymous.[105] The jacket is itself emblazoned with a painted circle-A. The creative director of the game, Eric Holmes, commented that "he looks like a street protester in our game and there's no accident to that".[106] This design was later used as model for a DC Collectibles figure, released as part of a series based on villains featured in the game.[101]

Reception

[edit]Impact on creators

[edit]"A large part of our relationship, especially when we got into doing Anarky, became a friendly philosophical debate over politics and conspiracy theory; mysticism versus scientism and all this other stuff. We came to really enjoy those debates, even when they (rarely) got a little heated".

—Norm Breyfogle, 2006.[107]

In the years that followed the creation of Anarky, both Norm Breyfogle and Alan Grant experienced changes in their personal and professional lives which they attributed to that collaboration. Each man acknowledged the primary impact of the character to have been on their mutual friendship and intellectual understanding. In particular, their time developing the Anarky series led to a working relationship centered on esoteric debate, discussion, and mutual respect.[5][6][107][108][109]

Over time, Anarky emerged as each man's favorite character, with Grant wishing he could emulate the character,[5][26][110] and remarking that "Anarky in Gotham City" was the most personal story he had ever written, and the foremost among his three favorite stories he had ever written for the Batman mythos.[111] Of Breyfogle, Grant complimented that the former "draws Anarky as if he loves the character".[58] While Breyfogle acknowledged that Anarky was his favorite of the creations they collaborated on,[28] he felt that his own appreciation was not as great as Grant's, commenting that Anarky was "Alan's baby".[109]

With the cancellation of the Anarky series, and the eventual departure of each artist from DC Comics—first by Grant, followed by Breyfogle—their mutual career paths split, and Anarky entered into a period of obscurity. During this period, Breyfogle came to suspect that the treatment each man, and Anarky, had received from their former employer was suspect.[6] While acknowledging that he lacked evidence, he held a "nagging feeling" that he and Grant had each been "blacklisted" from DC Comics as a result of the controversial views expressed in the Anarky series' second volume.[108]

While professing that Anarky was the character for whom he was proudest, and that the character's narratives were among his best achievements for the amount of reaction they generated among readers, the character was also a source of some regret for Grant. Reflecting on his early secret plan to transform Lonnie Machin into a new Robin, Grant has stated that though he came to appreciate the character of Tim Drake, he occasionally experiences "twinges of regret that Anarky wasn't chosen as the new sidekick for comics' greatest hero".[111] Grant has also stated that he attempted to distance himself from the direction of Anarky following his termination from DC Comics, and actively tried to avoid learning about the fate of Anarky and other characters he had come to care about. He often found himself disappointed to see how some characters were used or, as he felt, were mismanaged.[32][37] Grant later joked on his disillusion in the handling of Anarky, "if you create something that's close to your heart and you don't own it, 'Oh woe is me!'"[1] In 2011, DC Comics initiated a special DC Retroactive series of comics, exploring different periods in the publication history of popular characters. Both Grant and Breyfogle were invited to participate, and collaborated to reproduce a story in the style of their classic Batman: Shadow of the Bat series. Grant chose to author a story featuring the Ventriloquist. However, he had been tempted to author a story featuring Anarky, only reconsidering the idea on the basis that his disassociation from the character had left him unfamiliar with what had become of Anarky's canonical status at the time.[112]

As Anarky was created while Grant and Breyfogle were operating under "work-for-hire" rules, DC Comics owns all rights to the Anarky character. Following the cancellation of the Anarky series, both men attempted to buy the rights to Anarky from the company, but their offer was declined.[3][5]

Readership reaction

[edit]"My character Anarky - a 15-year-old vigilante kid - tried to put anarchist values into action. He's immensely popular - or, at least, he was - in countries like Mexico, Peru, Chile, and Argentina, where comic fans were able to empathize with his ethos a lot more than Americans did".

—Alan Grant, 2013.[80]

When an interviewer commented that Anarky was popular among fans in 2003, in the midst of the character's period of obscurity, Norm Breyfogle offered a caveat: "Well, in certain segments of the comic book industry, I suppose". Breyfogle continued: "It has some diehard fans. But, DC doesn't seem to want to do anything with him. Maybe it's because of his anti-authoritarian philosophy, a very touchy subject in today's world".[31]

The sense that Anarky is appreciated by certain fans is one shared by Alan Grant, who noted that the character's stories routinely generated more reader mail than any other he wrote.[111] Commenting on the popularity of the Anarky series, Grant acknowledged the failure of the series, but pointed out that it was very popular among some readers: "It wasn't terribly popular in the States, although I received quite a few letters (especially from philosophy students) saying the comic had changed their entire mindset. But Anarky was very popular in South America, where people have had a long and painful taste of totalitarianism, in a way the US is just entering".[3]

Sales of the Anarky limited series were high enough to green light an ongoing series,[67] with Breyfogle commenting, "[it] did well enough so that DC is willing to listen to Alan's idea for a sequel if we wanted to pitch them".[113] Despite the sales, Grant was still concerned the character lacked enough support among fans to sustain an ongoing series.[31] While the ongoing series did find an audience amongst Latin American nations - Mexico and Argentina in particular - it failed in the United States, where Alan Grant has lamented that the comic was doomed to eventual cancellation, as DC Comics "[doesn't] take foreign sales into consideration when counting their cash".[5]

Acknowledging the failure of the ongoing Anarky series, Grant has conceded that its themes, in particular his interest in exploring esoteric concepts such as philosophy of mind, likely resulted in "plummeting" sales.[5] Breyfogle claimed the difficulty of combining escapist entertainment with social commentary as his explanation for the series' failure. Breyfogle wrote at the time: "Anarky is a hybrid of the mainstream and the not-quite-so-mainstream. This title may have experienced exactly what every 'half-breed' suffers: rejection by both groups with which it claims identity".[114] Besides the themes, commentators have also found the escalation of Anarky's skills and special heroics as a source of criticism among readers. One critic for Fanzing, an online newsletter produced by comic book fans and professisonals, wrote: "I liked the original concept behind Anarky: a teenage geek who reads The Will to Power one too many times and decides to go out and fix the world. But the minute he wound up getting $100 million in a Swiss Bank account, owning a building, impressing Darksied [sic], getting a Boom Tube and was shown as being able to outsmart Batman, outhack Oracle and generally be invincible, I lost all interest I had in the character".[92]

In 2014, Comic Book Resources held an informal poll which asked readers to vote for the best characters within the Batman franchise, in celebration of the 75th anniversary of the 1939 creation of "the Caped Crusader". Anarky was placed at No. 31 among the best villains, coming nearly 25 years after the character's own creation.[115]

Political analysis and relevance

[edit]"Anarky is a direct contrast to Batman – he is an active agent of change while Batman is simply a reactive agent, reinforcing the status quo (as all corporate superheroes do) ... "

—Greg Burgas, 2006.[116]

The philosophical nature of the character has invited political critiques, and resulted in comparisons drawn against the political and philosophical views of other fictional characters. Of the various positive analyses drawn from Anarky, two points which are continuously touched upon by critics are that Anarky is among the most unusual of Batman's rogue gallery, and that his challenge to the ideologies of superheroes is his best feature.

The authors of "I'm Not Fooled By That Cheap Disguise", a 1991 essay deconstructing the Batman mythos, refer to Anarky as a challenge to Batman's social and political world view, and to the political position indirectly endorsed by the themes of a Batman adventure. As the Batman mythos is centered on themes of retribution and the protection of property rights, the invitation to readers to identify with Batman's vigilantism is an invitation to adopt political authoritarianism. The authors summarize that position as "the inviolability of property relations and the justification of their defense by any means necessary (short of death)". The authors commented that Anarky "potentially redefines crime" and invites the reader to identify with a new political position in favor of the disenfranchised, which Batman "can not utterly condemn". The authors also said that the creation of Anarky and dialogue by other characters represented a shift towards "self-conscious awareness of the Batman's hegemonic function, questioning the most central component of the Batman's identity—the nature of crime and his relation to it". However, the authors remained skeptical of Anarky's commercial nature, pointing out Anarky could be "incorporated as another marketing technique [...] The contradictions of capitalism would thus permit the commodification of criticisms as long as they resulted in profits".[117]

With the publication in 2005 of an issue of Green Arrow in which Anarky guest-starred, writer James Peaty juxtaposed Anarky's radical philosophy with the liberal progressive beliefs of Green Arrow: "Everyone always goes on about what a radical Ollie is and I wanted to show that maybe that isn't the case ... especially as Ollie's radical credentials are pretty antiquated ... Anarky as a character—and as a broader idea—is much more radical than Ollie".[34]

Greg Burgas, of Comic Book Resources, critiqued Anarky as "one of the more interesting characters of the past fifteen or twenty years [...] because of what he wants to accomplish...", comparing the nature of Anarky as a change agent against Batman: "He is able to show how ineffective Batman is against the real problems of society, and although Batman stops his spree, we find ourselves sympathizing much more with Anarky than with the representative of the status quo".[116]

Anarky's appearance in Batman: Arkham Origins included a speech delivered at the conclusion of the character's story arch. The player is given the opportunity to observe Anarky after he has been defeated, and watch as the teenager enters a monologue in which he laments the downfall of society, tries to reconcile his admiration for Batman, and ultimately denounces the Caped Crusader as a false hero. Nick Dinicola of PopMatters, in comparing the game to its predecessor, Batman: Arkham City, asserted that the narrative of Origins consistently challenged Batman's ideological reasons for acting as he does, whereas City uncritically took his motivations as a given: "Anarky's wonderful speech takes Batman to task for the contradictions in his symbolism. Considering that Batman is very explicitly a symbol of fear, Anarky is equating the rise of Batman with the downfall of society". Dinicola was also of the opinion that the willingness to use characters like Anarky to scrutinize Batman's heroism, rather than simply assert it, allowed the game to ultimately prove and uphold Batman as a heroic figure in a way City could not. To Dinicola, this validated the act of challenging a superhero's traditional interpretation in service to the story.[118]

In Batman and Philosophy, an analysis of various philosophies which intersect with the Batman mythos, Anarky's critique of the state is compared favorably to that of Friedrich Nietzsche: "The Nietzschean state constitutes a 'new idol', one that is no less repressive than its predecessors, as it defines good and evil for, and hangs a 'sword and a hundred appetites' over, the faithful. No Batman villain sees this as clearly as Anarky ..." However, Anarky's behavior was also interpreted as an attempt to impose an even more restrictive order, with examples presented from Batman: Anarky, in which Lonnie Machin lectures fellow juvenile detainees in "Tomorrow Belongs to Us", explains his motivations in a self-righteous farewell letter to his parents in "Anarky", and creates a fantasy dystopia in a distorted reflection of his desired society in "Metamorphosis": "His [Anarky's] search for an organizing principle that is less repressive than the state fails". This is sharply compared with Batman, described as moderating his impulses towards social control.[119] Dialogue from Detective Comics is employed, in which Batman compares himself to Anarky and denies the latter legitimacy: "The fact is, no man can be allowed to set himself up as judge, jury and executioner".[29]

Far less favorable views of Anarky have also been offered. Newsarama contributor George Marston was especially scathing of the character's politics and costume, placing Anarky at No.8 on a list of the "Top 10 Worst Batman villains of all time". Deriding the character as a "living embodiment of an Avril Lavigne t-shirt", he pointed out the pointlessness of being inspired to super heroics by radical philosophy, and the contradictory nature of fighting crime as an anarchist. He concluded by referring to the Anarky series as proof that "bad decisions are timeless".[120] Similarly, Cracked contributor Henrik Magnusson listed Anarky's debut at No.3 on a list of "5 Disastrous Attempts at Political Commentary in Comic Books". Magnusson's scorn focused on Anarky's speeches, which he derided as "pedantic" and laden with "pseudo-philosophical catchphrases". Referring to the original identity of Lonnie Machin as a "naive pre-teen", Magnusson considered this fine satire of "base-level philosophy" and teen rebellion. On the other hand, the understanding that Grant had intended Anarky to be a vehicle for his personal views, and that the "Anarky in Gotham City" narrative describes Batman as sympathetic to his goals, if not his methods, upset Magnusson.[121]

"I think Anarky's age is right now. He looks like a street protester. He looks like Anonymous. He's like one of these guys who wants to go out there and change the world to what he believes is the better, and I think of all the Batman enemies, and one of the reasons I'm most excited about Anarky, is he feels relevant today".

—Eric Holmes, 2013.[105]

Several global events of the early 2010s included the rise of hacktivist groups such as Anonymous and LulzSec; large scale protest movements, including the Arab Spring, Occupy movement, and Quebec student protests; the crypto-anarchist activity on the part of Defense Distributed and Cody Wilson; and the various information leaks to WikiLeaks by Chelsea Manning, the Stratfor email leak by Anonymous and Jeremy Hammond, and the global surveillance disclosures by Edward Snowden. The rapid succession of these events led some media commentators to insist that Anarky's relevance as a character had dramatically increased, and recommended that the character receive a higher profile in media.[45][116][122][123][124][125] This sentiment led the creative team that developed Batman: Arkham Origins to include Anarky in the game. Describing Anarky's anti-government and anti-corporate agenda, Holmes acknowledged the relevance of anarchism in the contemporary protest movements of the time as a factor in the choice to include the character in the game, and to update his appearance to that of a street protester with a gang resembling a social movement.[21] Holmes stressed in one interview: "In the real world, this is Anarky's moment. Right now. Today".[21] Even as early as 2005, James Peaty recommended that Anarky should be included in more publications in the midst of the ongoing War on Terror, stating "Anarky is a terrorist! How can that not be interesting in the modern climate?"[34]

Anarchist critique

[edit]"[Anarky] does represent the anarchist philosophy His whole point of existing is rolled up in his name. It's a philosophy of responsibility and freedom from the hierarchical power". [sic]

—Norm Breyfogle, 1999.[27]

Critics have commented on the character's depiction as an anarchist since his first appearance. According to Alan Grant, anarchists with whom he associated were angered by his creation of the character, seeing it as an act of recuperation for commercial gain.[110] Neither Grant nor Breyfogle could fully agree with this criticism. As Grant put it, "I thought I was doing them a favour you know?"[1]

In the years following the Anarky publications of the late 1990s, more receptive critiques have been offered. In assessing the presentation of anarchist philosophy in fiction, Mark Leier, the director for the Centre for Labour Studies from Simon Fraser University, cited Anarky as an example of the favorable treatment anarchist philosophy has occasionally received in mainstream comic books. Leier took particular note of quotations derived from the dialogue in "Anarky in Gotham City" story, in which Batman speaks positively of Anarky's intentions.[126] Following the cancellation of the ongoing series, Roderick T. Long, an anarchist/libertarian political commentator and Senior Scholar at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, praised Anarky as "an impressive voice for liberty in today's comics".[127] Margaret Killjoy's examination of anarchist fiction, Mythmakers & Lawbreakers, afforded Alan Grant and Anarky brief mention. Explaining the relationship Grant had with anarchism, Killjoy reviewed the characters' early incarnations as "quite wonderful".[128]

Greg Burgas, in reviewing the career of Alan Grant, specifically cited Anarky's anarchist philosophy as one of the character's most empathetic traits. Lamenting the obscurity of the character, Burgas wished Anarky and anarchism would be presented more often: "... anarchy as a concept is often dismissed, but it's worth looking at simply because it is so radical and untenable yet noble".[116]

Media

[edit]As a lesser known character in the DC Universe, Anarky has a smaller library of associated comic books and significant story lines than more popular DC Comics characters. Between 1989 and 1996, Anarky was primarily written by Alan Grant in Batman-related comics, received a guest appearance in a single issue of Green Arrow[72] by Kevin Dooley, and was given an entry in Who's Who in the DC Universe.[64]

In the late 1990s, Anarky entered a brief period of minor prominence; first with the publication of the first Anarky volume in 1997; followed in 1998 with the Batman: Anarky collection; and in 1999, with featured appearances in both DCU Heroes Secret Files and Origins #1,[129][130][131] and the second Anarky series. After the cancellation of the ongoing series, Anarky lapsed into obscurity lasting approximately nine years. This ambiguous condition was not complete, as Anarky was sporadically used during this time. These appearances include marginal cameos in issues of Young Justice,[132][133] Wonder Woman,[134] and Green Arrow.[33]

Lesser known among the cast of characters in the DC universe, Anarky went unused for adaptations to other media platforms throughout much of the character's existence. In 2013 the character was chosen to recur in Beware the Batman, an animated series on Cartoon Network, voiced by Wallace Langham.[135] Anarky debuted in the third episode, "Tests", and appeared in seven total episodes of the series before its cancellation.[20] Later that year, Anarky was also included in the Batman video game, Batman: Arkham Origins, voiced by Matthew Mercer,[136] and Scribblenauts Unmasked: A DC Comics Adventure.[137] Lonnie Machin made his live action debut in 2016, during the fourth season of Arrow, in a villainous adaptation portrayed by Alexander Calvert.[22][138]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]I. ^ 52 was promoted as a comic that would attempt to incorporate as many DC Comics characters as possible. In a Q&A session hosted by Newsarama.com, 52 editor Michael Siglain answered a series of questions regarding which characters fans wanted to see in the series. Question No.19 asked: "We were told Anarky would be playing a part in 52. Could you please tell us when we can expect his appearances?" Siglain's simple response to readers was, "check back in the late 40s".[139] Speculation centered on the prospect of Anarky appearing in issue No.48 of the series, as the solicited cover illustration was released to the public several weeks before the issues' publication. On the cover, the circle-A could be seen as a minor element in the background. In a review for "Week 48", Major Spoilers considered the absence of Anarky a drawback: "It's too bad we didn't see the return of Anarky as hinted by this week's cover".[140] Pop culture critic, Douglas Wolk, wrote: "I guess this issue's cover is the closest we're going to get to Anarky after all (and by proxy as close as we're going to get to the Haunted Tank). Too bad".[141]

II. ^ The 1990 Detective Comics #620 story, "Rite of Passage Part 3: Make Me a Hero", chronicles Tim Drake's first solo detective case, as he pursues an online investigation against an advanced grey hat computer hacker. The unknown hacker, operating under the alias "Moneyspider", has stolen millions of dollars from Western corporations, including Wayne Enterprises, outmaneuvering Batman's own data security in the process. He is revealed by Drake to be Lonnie Machin by the end of the issue.[83] This functioned as the antecedent for Fabian Nicieza's reintroduction of Machin under the name "Moneyspider" in 2008.

III. ^ As a result of the increased renown the character gained from this appearance, speculation that Anarky would reappear in the Batman: Arkham franchise simmered in the lead-up to the release of Batman: Arkham Knight, with commentators predicting that the enigmatic "Arkham Knight" character would be revealed to be Anarky in adult form.[142][143]

IV. ^ In warning readers to avoid spoiling potential surprises for their experience in playing Batman: Arkham Origins, Eric Holmes specifically referenced the Wikipedia article on the character as a resource to avoid: "You know what? If you want to enjoy the game, don't bother reading up on him, because there are a few surprises about him which will turn up in the game, and if you go read Wikipedia or something like that, it'll rob you a little bit on some of the stuff in the game, because there are some surprises about Anarky".[144]

V. ^ Following Anarky's debut in "Anarky in Gotham City", the character's design incorporated the head extender in Robin Annual #1 (1992),[50] Green Arrow #89 (August 1994),[72] and The Batman Adventures #31 (April 1995).[63] The head extender was not included in Batman: Shadow of the Bat #18 (October 1993),[81] and The Batman Chronicles #1 (summer 1995).[145]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Best, Daniel (January 6, 2007). "Alan Grant & Norm Breyfogle". Adelaide Comics and Books. ACAB Publishing. Archived from the original on April 27, 2007. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Kraft, Gary S. (April 8, 1997). "Holy Penis Collapsor Batman! DC Publishes The First Zonpower Comic Book!?!?!". GoComics.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 1998.

- ^ a b c d e f Berridge, Edward (January 12, 2005). "Alan Grant". 2000 AD Review. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ a b Redington, James (September 20, 2005). "The Panel: Why Work In Comics?". Silverbulletcomics.com. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cooling, William (July 21, 2004). "Getting The 411: Alan Grant". 411Mania.com. Archived from the original on November 13, 2005. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Best, Daniel (2003). "Norm Breyfogle @ Adelaide Comics and Books". Adelaide Comics and Books. ACAB Publishing. Archived from the original on January 31, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ "NYCC: DCU — Better Than Ever Panel". newsarama.com. Newsarama.com, LLC. Archived from the original on May 24, 2006. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

Referring to all the requests for Anarky appearing in 52 that were made two weeks ago at WonderCon, Didio said that since that San Francisco show, the writers have come up with a way to include the character in the story.

- ^ a b "ROBIN No.181". dccomics.com. Warner Bros. September 15, 2008. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ^ "ROBIN No.182". dccomics.com. Warner Bros. October 15, 2008. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ^ Brady, Matt (September 15, 2008). "January Sees 'Faces of Evil' at DC — Dan DiDio Spills". newsarama.com. Imaginova Corp. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Nicieza, Fabian (December 20, 2008). "Fabian Nicieza Q&A Thread for Robin". The Comic Bloc. Comic Bloc. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved December 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c Nicieza, Fabian (June 8, 2009). "How Do Comic Writers Feel..." The Comic Bloc. Comic Bloc. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ^ a b Hyde, David (August 17, 2011). "Super Hero Fans Expected to Line-Up Early as DC Entertainment Launches New Era of Comic Books". The Source. DC Comics.

- ^ a b Jensen, Van, Robert Venditti (w), Drujiniu, Victor, Ivan Fernandez, Allan Jefferson, Bernard Chang (p), Castro, Juan, Rob Lean (i), Conroy, Chris (ed). "Powers That Be" Green Lantern Corps, vol. 1, no. 25 (November 13, 2013). New York, NY: DC Comics.

- ^ a b Rogers, Vaneta (August 7, 2014). "MANAPUL, BUCCELLATO Bring 'ANARKY' to DETECTIVE COMICS". Newsarama. Newsarama.com. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Francis Manapul, Brian Buccellato (w), Francis Manapul (p), Francis Manapul (i). "Anarky Part 1" Detective Comics, vol. 2, no. 37 (February 2015). DC Comics.

- ^ a b Wilson, Daniel H. (w), Borges, Alison, Jimenez, Jorge (a), Sanchez, Alejandro; Blond (col). "Godhood" Earth 2: Society, no. 6 (November 18, 2015). DC Comics.

- ^ Williams, Mike (October 25, 2013). "Batman: Who's Who in Arkham Origins". Usgamer.net. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ Keith Veronese (July 19, 2012). "Bruce Wayne goes back to his detective roots, in Beware the Batman". io9. Gawker Media. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c Collura, Scott (July 29, 2013). "Bruce sees if Tatsu has what it takes". IGN.com. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ^ a b c d O'Dwyer, Danny; Holmes, Eric (2013). Batman: Arkham Origins - E3 2013 Stage Demo. Gamespot (video podcast). Youtube. 8:59 minutes in. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Tyrrel, Brandin (July 11, 2015). "Comic Con 2015: Anarky, Mr. Terrific Coming to CW's Arrow". IGN. ign.com. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ^ Breyfogle, Norm. "Norm's favorites". Normbreyfogle.com. Archived from the original on March 28, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Grant, Alan (1999). "Intro by Alan Grant". Batman: Anarky. New York, NY: DC Comics. pp. 3–4. ISBN 1-56389-437-8.

- ^ Grunenwald, Joe (November 29, 2018). "The Lives and Death of Jason Todd: An Oral History of The Second Robin and A DEATH IN THE FAMILY". ComicsBeat.com. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Klaehn, Jeffery (March 14, 2009). "Alan Grant on Batman and Beyond". Graphicnovelreporter.com. Midlothian, VA: The Book Report, Inc. Archived from the original on June 1, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i H-C Chan, Vera (April 9, 1999). "Comic Un-Conventions". Contra Costa Times. Walnut Creek, CA: MediaNews Group. p. TO26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Breyfogle, Norm (1999). "Intro by Norm Breyfogle". Batman: Anarky. New York, NY: DC Comics. pp. 5–6. ISBN 1-56389-437-8. Archived from the original on December 18, 2006. Retrieved February 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Alan Grant (w), Norm Breyfogle (p), Steve Mitchell (i). "Anarky in Gotham City, Part 1: Letters to the Editor" Detective Comics, no. 608 (November 1989). DC Comics.

- ^ a b c d Alan Grant (w), Norm Breyfogle (p), Steve Mitchell (i). "Anarky in Gotham City, Part 2: Facts About Bats" Detective Comics, no. 609 (December 1989). DC Comics.

- ^ a b c d e Carey, Edward (October 10, 2006). "Catching Up With Norm Breyfogle and Chuck Satterlee". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ a b Luiz, Lucio (March 7, 2005). "Lobo Brasil interview: Alan Grant". Lobobrasil.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c James Peaty (w), Eric Battle (p), Jack Purcell (i). "Anarky in the USA" Green Arrow, vol. 3, no. 51 (July 31, 2005). DC Comics.

- ^ a b c d M. Contino, Jennifer (June 7, 2005). "James Peaty Pens Green Arrow". Comicon.com Pulse. Diamond International Galleries. Archived from the original on October 21, 2007. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- ^ a b c Fabian Nicieza (w), Freddy Williams II (a), Guy Major (col), John J. Hill (let). "Search For a Hero, Part 5: Pushing Buttons, Pulling Strings" Robin, vol. 2, no. 181 (December 17, 2008). DC Comics.

- ^ Long, Roderick (January 15, 2009). "Evil Reigns at DC". Austro-Athenian Empire. Aaeblog.com. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ a b Forrest, Adam (February 12, 2009). "Superheroes — made in Scotland". Bigissuescotland.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ Yost, Christopher (w), Bachs, Ramon (p), Major, Guy (i), Major, Guy (col), Cipriano, Sal (let). "The Grail, Part Three of Four" Red Robin, no. 3, p. 14/1 (October 2009). DC Comics.

- ^ Renaud, Jeffrey (April 1, 2010). "Nicieza Returns to Tim Drake in "Red Robin"". comicbookresources.com. Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on April 5, 2010. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

... I'll be bringing back characters I'd percolated in my previous run, villains like Lynx, Scarab, Anarky and Moneyspider.

- ^ a b Nicieza, Fabian (w), Williams II, Freddy (a), McCarthy, Ray (i), Major, Guy (col), Cipriano, Sal (let), Ryan, Sean (ed). "The Hit List, Part Four: The Best Laid Plans" Red Robin, no. 16 (December 2010). DC Comics.

- ^ a b Ching, Albert (October 1, 2013). "Players Guide a Young Batman's Long Christmas in "Arkham Origins"". Comicbookresources.com. Comic Book Resources. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ "DC Comics' FULL November 2013 Solicitations". Newsarama. August 12, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ Ching, Albert (October 13, 2013). "NYCC: Green Lantern - "Lights Out" Panel". Comicbookresources.com. Comic Book Resources. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ Sailer, Peter (October 13, 2013). "Green Lantern: Lights Out – The Spoilerific Panel Recap". Bleedingcool.com. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Asburry, Andrew (November 14, 2013). "Green Lantern Corps #25 review". Batman News. Batman-news.com. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Francis Manapul, Brian Buccellato (w), Francis Manapul (p), Francis Manapul (i). "Anarky Conclusion" Detective Comics, vol. 2, no. 40 (May 2015). DC Comics.