Cleansing of the Temple

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

In all four canonical gospels of the Christian New Testament, the cleansing of the Temple narrative tells of Jesus expelling the merchants and the money changers from the Temple. The scene is a common motif in Christian art.

In this account, Jesus and his disciples travel to Jerusalem for Passover, where Jesus expels the merchants and consumers from the temple, accusing them of turning it into "a den of thieves" (in the Synoptic Gospels) and "a house of trade" (in the Gospel of John) through their commercial activities.

The narrative occurs near the end of the Synoptic Gospels (at Matthew 21:12–17,[1] Mark 11:15–19,[2] and Luke 19:45–48)[3] and near the start of the Gospel of John (at John 2:13–16).[4] Some scholars believe that these refer to two separate incidents, given that the Gospel of John also includes more than one Passover.[5]

Description

[edit]

In the narrative, Jesus is stated to have visited the Temple in Jerusalem, where the courtyard was described as being filled with livestock, merchants, and the tables of the money changers, who changed the standard Greek and Roman money for Jewish and Tyrian shekels.[6] Jerusalem was packed with Jews who had come for Passover, perhaps numbering 300,000 to 400,000 pilgrims.[7][8]

And when he had made a scourge of small cords, he drove them all out of the temple, and the sheep, and the oxen; and poured out the changers' money, and overthrew the tables; And said unto them that sold doves, Take these things hence; make not my Father's house a house of merchandise.

— John 2:15–16, King James Version[9]

And Jesus went into the temple of God, and cast out all them that sold and bought in the temple, and overthrew the tables of the money changers, and the seats of them that sold doves, And said unto them, It is written, My house shall be called the house of prayer; but ye have made it a den of thieves.

— Matthew 21:12–13, King James Version[10]

In Mark 12:40[11] and Luke 20:47,[12] Jesus accuses the Temple authorities of thieving and, in this instance, names poor widows as their victims, going on to provide evidence of this in Mark 12:42[13] and Luke 21:2.[14] Dove sellers were selling doves to be sacrificed by the poor, specifically by women, who could not afford grander sacrifices. According to Mark 11:16,[15] Jesus then put an embargo on people carrying any merchandise through the Temple, a sanction which would have disrupted all commerce.[5][16] This occurred in the outermost court, the Court of the Gentiles, which was where the buying and selling of animals took place.[17]

Matthew 21:14–16[18] says the Temple leaders questioned Jesus, asking whether he was aware that the children were shouting "Hosanna to the Son of David". Jesus responded by saying, "From the lips of children and infants you have ordained praise." This phrase incorporates a phrase from the Psalm 8:2,[19] "from the lips of children and infants," believed by followers to be an admission of divinity by Jesus.[5][16]

Chronology

[edit]There are debates about when the cleansing of the Temple occurred and whether there were two separate events. Thomas Aquinas and Augustine agree that Jesus performed a similar act twice, with the less severe denunciations of the Johannine account (merchants, sellers) occurring early in Jesus's public ministry and the more severe denunciations of the synoptic accounts (thieves, robbers) occurring just before, and indeed expediting, the events of the crucifixion.[citation needed]

Claims about the Temple cleansing episode in the Gospel of John can be combined with non-biblical historical sources to obtain an estimate of when it occurred. John 2:13 states that Jesus went to the Temple in Jerusalem around the start of his ministry and John 2:20 states that Jesus was told: "Forty and six years was this temple in building, and you want to raise it up in three days?"[20][21]

In the Antiquities of the Jews, first-century historian Flavius Josephus wrote that (Ant 15.380) the temple reconstruction was started by Herod the Great in the 18th year of his reign 22 BC, two years before Augustus arrived in Syria in 20 BC to return the son of Phraates IV and receive in return the spoils and standards of three Roman legions (Ant 15.354).[21][22][23][24] Temple expansion and reconstruction was ongoing, and it was in constant reconstruction until it was destroyed in 70 AD by the Romans.[25] Given that it had taken 46 years of construction to that point, the Temple visit in the Gospel of John has been estimated at any time between 24–29 AD. It is possible that the complex was only a few years completed when the future Emperor Titus destroyed the Temple in 70 AD.[20][21][26][27][28]

Analysis

[edit]

Professor David Landry of the University of St. Thomas suggests that "the importance of the episode is signaled by the fact that within a week of this incident, Jesus is dead. Matthew, Mark, and Luke agree that this is the event that functioned as the 'trigger' for Jesus' death."[29]

Butler University professor James F. McGrath explains that the animal sales were related to selling animals for use in the animal sacrifices in the Temple. He also explains that the money changers in the temple existed to convert the many currencies in use into the accepted currency for paying the Temple taxes.[30] E. P. Sanders and Bart Ehrman say that Greek and Roman currency was converted to Jewish and Tyrian money.[6][31]

A common interpretation is that Jesus was reacting to the practice of money changers routinely cheating the people, but Marvin L. Krier Mich observes that a good deal of money was stored at the temple, where it could be loaned by the wealthy to the poor who were in danger of losing their land to debt. The Temple establishment therefore co-operated with the aristocracy in the exploitation of the poor. One of the first acts of the First Jewish-Roman War was the burning of the debt records in the archives.[32]

Pope Francis sees the Cleansing of the Temple not as a violent act but more of a prophetic demonstration.[33] In addition to writing and speaking messages from God, Israelite or Jewish nevi'im ('spokespersons', 'prophets') often acted out prophetic actions in their life.[34]

According to D.A. Carson, the fact that Jesus was not arrested by the Temple guards was due to the fact that the crowd supported Jesus's actions.[35] Maurice Casey agrees with this view, stating that the Temple's authorities were probably afraid that sending guards against Jesus and his disciples would cause a revolt and a carnage, while Roman soldiers in the Antonia Fortress did not feel the need to act for a minor disturbance such as this; however, Jesus's actions probably prompted the authorities' decision to have Jesus arrested some days later and later had him crucified by Roman prefect Pontius Pilate.[36]

Some scholars such as those in the Jesus Seminar as expressed in the book The Acts of Jesus (1998) and others question the historicity of the incident as expressed in the Gospels in light of the fact of the vastness of the temple complex. In The Acts of Jesus, the Jesus Seminar scholars assert the area of the temple complex is equivalent to "thirty-four football fields". In that book, those in Jesus Seminar further assert that during the great festivals such as Passover, there would be "thousands of pilgrims" in that area. Those in the Jesus Seminar do feel Jesus "performed some anti-temple act and spoke some word against the temple".[37]

John Dominic Crossan argues that Jesus was not attempting to cleanse the Temple of any corruption. Instead, it was a radical protest against the institution of animal sacrifice, which gave people a false sense of transactional forgiveness compared to repentance. He believes these views aligned with John the Baptist and Jeremiah.[38][39]

Interpretation of John 2:15

[edit]In 2012, Andy Alexis-Baker, clinical associate professor of theology at Loyola University Chicago, gave the history of the interpretation of the Johannine passage since Antiquity:[40]

- Origen (3rd century) is the first to comment on the passage: he denies historicity and interprets it as metaphorical, where the Temple is the soul of a person freed from earthly things thanks to Jesus. On the contrary, John Chrysostom (v. 391) defended the historical authenticity of this passage, but if he considered that Jesus had used the whip against the merchants in addition to the other beasts, he specified that it was to show his divinity and that Jesus was not to be imitated.

- Theodore of Mopsuestia (in 381) – who answered, during the First Council of Constantinople, to the bishop Rabbula, accused of striking his clerics and to justify himself by the purification of the Temple – and Cosmas Indicopleustes (v. 550) supported that the event is non-violent and historical: Jesus whips sheep and bulls, but speaks only to merchants and only overturns their tables.

- Augustine of Hippo (in 387) referred to cleansing of the temple to justify rebuking others for their sinful behavior writing, "Stop those whom you can, restrain whom you can, frighten whom you can, allure gently whom you can, do not, however, rest silent."[41]

- Pope Gregory VII (in 1075), quoting Pope Gregory I, relies on this passage to justify his policy against simoniacal clergy, comparing them to merchants. Other medieval Catholic figures will do the same, such as Bernard of Clairvaux, who justified the Crusades by claiming that fighting the "pagans" with the same zeal that Jesus displayed against the merchants was a way to salvation.

- During the Protestant Reformation, John Calvin (in 1554), in line with Augustine of Hippo and the Gregories, defended himself by using (among other things) the purification of the temple, when he was accused of having helped to burn alive Michael Servetus, a theologian who disputed the idea of the Holy Trinity.

- Andy Alexis-Baker indicates that, while the majority of English-speaking Bibles include humans, sheep and cattle in the whipping, the original text is more complex and, after grammatical analysis, concludes that the text does not describe a violent act of Jesus against the merchants.[40]

According to later sources

[edit]Toledot Yeshu

[edit]There are a number of later narratives of the incident that are generally regarded as legendary or polemical by scholars. One example is the Toledot Yeshu, a parody gospel probably first written about 1,000 years after Christ, but possibly dependent on second-century Jewish-Christian gospel[42] and not oral traditions that might go back all the way to the formation of the canonical narratives themselves.[43] The Toledot Yeshu claims that Yeshu had entered the Temple with 310 of his followers. That Christ's followers had indeed entered the Temple, and in fact the Holy of Holies,[44] is also claimed by Epiphanius, who further claimed that James wore the breastplate of the high priest and the high priestly diadem on his head and actually entered the Holy of Holies,[45] and that John the Beloved had become a sacrificing priest who wore the mitre,[46] which was the headdress of the high priest.

Yeshu is likewise portrayed as robbing the shem hamephorash, the 'secret name of god' from the Holy of Holies, in the Toledot Yeshu.[47]

In art

[edit]The cleansing of the Temple is a commonly depicted event in the Life of Christ, under various titles.

El Greco painted several versions:

- Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple (El Greco, London)

- Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple (El Greco, Madrid)

- Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple (El Greco, Minneapolis)

- Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple (El Greco, New York)

- Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple (El Greco, Washington)

Gallery

[edit]-

Cleansing of the Temple. Unknown artist

-

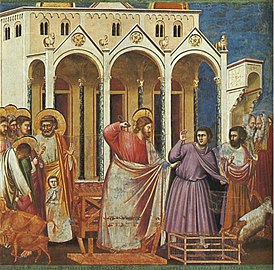

Casting out the money changers by Giotto

-

Christ driving the money changers from the temple by Jan Sanders van Hemessen

-

Christ Expelling the Money-Changers from the Temple by Nicolas Colombel

-

Christ Cleansing the Temple by Bernardino Mei

-

Expulsion of the merchants from the temple by Andrei Mironov

-

Jesus (top left) lashes out at money changers with a whip. Rembrandt (1626).

-

Cleansing of the Temple by Enrique Simonet

See also

[edit]- Christian views on poverty and wealth – Different opinions that Christians have held about material riches

- Gessius Florus

- Gospel harmony

- Ministry of Jesus

Notes

[edit]- ^ Matthew 21:12–17

- ^ Mark 11:15–19

- ^ Luke 19:45–48

- ^ John 2:13–16

- ^ a b c "The Temple Cleansing (13–25)". pp. 49–51. In Burge, Gary M (2005). "Gospel of John". In Evans, Craig A. (ed.). The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: John's Gospel, Hebrews-Revelation. David C Cook. pp. 37–163. ISBN 978-0-7814-4228-2.

- ^ a b Sanders 1995, p. [page needed].

- ^ Sanders 1995, p. 249.

- ^ Funk 1998.

- ^ John 2:15–16

- ^ Matthew 21:12–13

- ^ Mark 12:40

- ^ Luke 20:47

- ^ Mark 12:42

- ^ Luke 21:2

- ^ Mark 11:16

- ^ a b The Fourth Gospel And the Quest for Jesus by Paul N. Anderson 2006 ISBN 0-567-04394-0 page 158

- ^ Nyland, Jan (2016). The Lexham Bible Dictionary (PDF). Lexham Press.

- ^ Matthew 21:14–16

- ^ Psalm 8:2

- ^ a b Paul L. Maier "The Date of the Nativity and Chronology of Jesus" in Chronos, Kairos, Christos: Nativity and Chronological Studies by Jerry Vardaman, Edwin M. Yamauchi 1989 ISBN 0-931464-50-1 pages 113–129

- ^ a b c Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible 2000 Amsterdam University Press ISBN 90-5356-503-5 page 249

- ^ Köstenberger, Kellum & Quarles 2009, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Evans, Craig A. (2008). Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-415-97569-8.

- ^ As stated by Köstenberger, Kellum & Quarles 2009, p. 114, there is some uncertainty about how Josephus referred to and computed dates, hence various scholars arrive at slightly different dates for the exact date of the start of the Temple construction, varying by a few years in their final estimation of the date of the Temple visit.

- ^ Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, page 246 states that Temple construction never completed, and that the Temple was in constant reconstruction until it was destroyed in 70 AD/CE by the Romans, and states that the 46 years should refers to the actual number of year from the start of the construction.

- ^ Anderson, Paul N. (2006). The Fourth Gospel and the Quest for Jesus: Modern Foundations Reconsidered. T & T Clark. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-567-04394-8.

- ^ Knoblet, Jerry (2005). Herod the Great. University Press of America. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-7618-3087-0.

- ^ "Interlocking between John and the Synoptics". pp. 77–79. In Blomberg, Craig L (2001). "The historical reliability of John: Rushing in where angels fear to tread?". In Fortna, Robert Tomson; Thatcher, Tom (eds.). Jesus in Johannine Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 71–82. ISBN 978-0-664-22219-2.

- ^ Landry, David (October 2009). "God in the Details: The Cleansing of the Temple in Four Jesus Films". Journal of Religion & Film. 13 (2). doi:10.32873/uno.dc.jrf.13.02.05.

- ^ McGrath, James F. "Jesus and the Money Changers". Bible Odyssey.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. Jesus, Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (And Why We Don't Know About Them), HarperCollins, 2009. ISBN 978-0-06-117393-6[page needed]

- ^ Mich, Marvin L. Krier. The Challenge and Spirituality of Catholic Social Teaching, Chapter 6, Orbis Books, 2011, ISBN 978-1-57075-945-1[page needed]

- ^ Pope Francis. "Angelus Address: Jesus Cleanses the Temple of Jerusalem". Zenit, March 4, 2018. Translated from the Italian by Virginia M. Forrester.

- ^ Lockyer, Herbert. All the Parables of the Bible, Zondervan, 1988. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-310-28111-5

- ^ Dansby, Jonathan. THE NEW TEMPLE: AN EXEGESIS OF JOHN 2:12–22 (Report).[page needed][unreliable source?]

- ^ Casey, P. M. (1997). "Culture and Historicity: The Cleansing of the Temple". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 59 (2): 306–332. JSTOR 43722943.

- ^ Funk 1998, p. 121, 231, 338, 373.

- ^ Crossan, John Dominic (1999). The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant. HarperCollins Religious US. ISBN 978-0-06-061629-8.[page needed]

- ^ Crossan, John Dominic (2010). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. HarperCollins Religious US. ISBN 978-0-06-180035-1.[page needed]

- ^ a b Alexis-Baker, Andy (2012). "Violence, Nonviolence and the Temple Incident in John 2:13-15". Biblical Interpretation. 20 (1–2): 73–96. doi:10.1163/156851511X595549.

- ^ of Hippo, Augustine (1886). "Tractate 10 (John 2:12-21)". A Select library of the Nicene and post-Nicene fathers of the Christian church. Vol. 7. New York: The Christian literature Co.

- ^ Price, Robert (2003) The Incredible Shrinking Son of Man, p. 40.

- ^ Alexander, P. 'Jesus and his Mother in the Jewish Anti-Gospel (the Toledot Yeshu)', in eds. C. Clivaz et al., Infancy Gospels, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck GmbH & Co. KG, 2011, pp. 588–616.

- ^ Goldstein, Morris. Jesus in the Jewish Tradition. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1950, p. 152.

- ^ Bauckham, The Testimony of the Beloved Disciple, p. 45.

- ^ Eisenman, Robert, Maccabees, Zadokites, Christians, and Qumran: A New Hypothesis of Qumran Origins. Nashville, TN: Grave Distractions Publications, 2013, p. 10.

- ^ Zindler, Frank R. The Jesus the Jews Never Knew. Cranford, NJ: American Atheist Press, 2003, pp. 318–319, 428–431.

References

[edit]- Brown, Raymond E. An Introduction to the New Testament, Doubleday (1997) ISBN 0-385-24767-2

- Brown, Raymond E. The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, Prentice Hall (1990) ISBN 0-13-614934-0

- Funk, Robert W. (1998). The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. with the Jesus Seminar. HarperSanFrancisco.

- Miller, Robert J. The Complete Gospels, Polebridge Press (1994), ISBN 0-06-065587-9

- Myers, Ched. Binding the Strong Man: A political reading of Mark's story of Jesus. Orbis (1988) ISBN 0-88344-620-0

- Köstenberger, Andreas J.; Kellum, Leonard Scott; Quarles, Charles Leland (2009). The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3.

- Sanders, E. (1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-192822-7.