Monastery of Saint Pishoy

| |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Deir Abu Bishoy |

| Established | 4th century |

| Dedicated to | Pishoy |

| Diocese | Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Pishoy |

| Important associated figures | Pope Gabriel VIII Pope Macarius III Pope Shenouda III Paul of Tammah |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Coptic |

| Site | |

| Location | Wadi El Natrun |

| Country | |

| Coordinates | 30°19′9″N 30°21′36″E / 30.31917°N 30.36000°E |

| Public access | Yes |

The Monastery of Saint Pishoy (also spelled Bishoy, Pshoi, or Bishoi),[1] also known as Saint Pishoy Monastery,[2] is a Coptic Orthodox monastery in Wadi El Natrun,[3][4] west of the Nile Delta in northern Egypt.[5] It is the largest active monastery in the region and is currently headed by Bishop Anba Agabius.[6] Founded in the late 4th century AD by Saint Pishoy, a disciple of Saint Macarius, the monastery serves as a prominent religious and monastic site.

Spanning approximately two feddans, the monastery contains five churches, including the Church of Saint Pishoy, the largest church in Wadi El Natrun. Additional features include a guesthouse, expansive gardens, a library, an ancient refectory, and the Well of the Martyrs, as well as apartments where monks reside.[7] Pope Shenouda III often visited the monastery for seclusion, sometimes as a form of symbolic protest against various issues.[8]

History

[edit]The Monastery of Saint Pishoy, initially established as a monastic community under Saint Pishoy in the late 4th century AD, is one of the oldest monastic settlements in Wadi El Natrun. Founded contemporaneously with Saint Macarius the Great, the monastery originally comprised a cluster of monks' apartments and a central church built around Saint Pishoy's cave, with no defensive walls.[9]

In 407 AD, the church was destroyed in a raid by Libyan Bedouins, marking the first of several such incursions. Subsequent attacks in 434 and 444 AD caused further destruction,[10] and a fourth Berber raid in the late 6th century severely damaged the church and the fortified tower. Restoration efforts were led by Pope Benjamin I in 645 AD, which included rebuilding both structures.[11]

Another raid occurred in 817 AD, prompting further repairs by Pope Jacob I, while Pope Joseph I returned the relics of Saints Pishoy and Paul of Tammah to the site and oversaw the construction of the main church,[12] which dates back to 840 AD.[13] In 1069 AD, the Berber Luata tribe invaded the monastery, leading to additional reconstruction under Pope Benjamin II in 1319 AD, who was later interred in the main church. The monastery was noted by the historian Al-Maqrizi in the 15th century for its extensive grounds, despite being in a state of disrepair.[14]

During the papacy of Pope Shenouda III, the Monastery of Saint Pishoy underwent renovations. He initiated the restoration of the monks' apartments and repaired the water well where the Berbers had washed their swords after the massacre of the Forty-Nine Martyrs of Scetis. Additionally, Pope Shenouda allocated approximately 300 acres of surrounding desert for land reclamation, established a private papal retreat, and facilitated the introduction of electricity to the monastery.[15]

Notably, the holy oil of chrism (myron) was prepared at the monastery five times during his tenure, specifically in 1981, 1987, 1990, 1995, and 2008. This myron was distributed to Coptic churches both within Egypt and abroad, highlighting the monastery's role in the broader Coptic Orthodox community during his leadership.[16]

About monastery

[edit]

The Monastery of Saint Pishoy, also known as the Beloved of Christ, is the largest monastery in Wadi Natrun by area, covering approximately two feddans and 16 qirats, excluding additional land. The monastery has a quadrilateral shape and is enclosed by surrounding walls.[17] The entrance is located at the western end of the northern wall. Within the monastery complex, several important buildings can be found, notably a fortress situated in the northwest corner.[18]

The Church of Saint Pishoy is located in the southern part of the monastery, accompanied by various annexes, including "the Table" to the west, the altar of Saint Benjamin's Church to the north, the Church of Abu Sakhiron, the Church of Saint George, and a baptistery to the south.[19] The central area features a garden surrounded by several buildings. To the north, there are relatively modern monks' apartments built approximately 60 years ago, topped with a roof structure. The southern side contains apartments dating back to the ninth century that are still in use, while newly constructed apartments are located on the eastern side. The western side overlooks the monks' cemetery, known as "the Taphos." Adjacent to the southern wall, there are older monk apartments covered by vaults.

In the southeastern corner of the monastery are the kitchen, an old mill, and an ancient bakery. To the north, a former second row of apartments has since collapsed and has been replaced by a new guesthouse built by the monastery's head, Father Peter, in 1926. [20]The monastery also houses a library, considered one of the smallest among monasteries. Originally located in the fortress, the library was later moved to a dedicated building on the ground floor of the new guesthouse, and subsequently relocated to a room above the guesthouse adjacent to the northern wall. A larger library was established during the tenure of the current pope in 1989.[21]

Numerous expansions occurred during Pope Shenouda III's tenure, particularly on the southern side behind the ancient wall, where a retreat house for newly ordained priests was constructed, along with a four-story guesthouse. The monastery now features seven gates and towers topped with crosses, as well as a designated residence for the pope, adjacent to a museum store for preserving the monastery's artifacts. The walls, fortress, and Church of Saint Pishoy have been restored under the supervision of the Egyptian Antiquities Authority.[22]

Alqalali

[edit]

The apartment called Alqalali serve as the living quarters for monks and typically consist of two rooms, a bathroom, and a small reception area. The inner room, known as the "Mahbasa", functions as a retreat for the monk to engage in prayer and spiritual contemplation. [23]The windows of both the apartment and the Mahbasa are designed with southern openings to ensure proper ventilation during both winter and summer.

In addition to a few older apartments located near the southern wall of the monastery, modern apartments have been constructed along the northern and eastern walls. The apartments adjacent to the northern wall were built by Father Yohanna Michael, the head of the monastery, in 1934, replacing older apartments that previously occupied the site. Meanwhile, the apartments next to the eastern wall were established by Pope Shenouda III in 1978.[24]

Notably, the older apartments, which each consisted of two rooms, were removed to make way for these modern constructions. [25]Previously, there was a row of apartments in the northern area of the monastery, another row along the southern edge of the enclosed area, and yet another row parallel to the dining area; however, these have since fallen into ruins.[26]

The construction of the monks' apartments(known as Alqalali ) was completed in stages, culminating in 1983. By this time, the layout resembled the letter "U" and comprised two stories, accommodating approximately 60 apartments. This complex also included a communal dining area, an attached kitchen, food storage rooms, and bathrooms.

In addition, another building shaped like the letter "T" was constructed, featuring three floors that house around 45 apartments, each equipped with an attached bathroom. A water tank with a capacity of 89 cubic meters is also present, which includes recovery rooms for individuals requiring special medical care.

In 1980, a building shaped like the letter "I" was completed, consisting of two floors and containing approximately 26 apartments, each with an attached bathroom. Furthermore, in 1988, a three-story building was erected, featuring numerous apartments, all equipped with attached bathrooms.[27]

By 1989, a large wall was completed around these three buildings and the surrounding gardens to maintain the tranquility of the area where the monks worship. In addition to the communal apartments for monks living in community, there are also individual apartments for hermitic monks, each with a small garden. Some of these apartments are situated 2 to 5 kilometers away from the monastery, providing solitude for those seeking a more isolated monastic life.[28]

The table

[edit]

Adjacent to the western end of the main church in the monastery, known as the Church of St. Bishoy, lies the dining hall Known as Al-Ma'eda. This hall is separated from the church by a corridor that runs the length of the church. Its origins can be traced back to the late 11th or early 12th century, suggesting that the corridor is not structurally distinct from the dining hall itself or the building in the northwestern corner of the church, which shares its historical context with the monastery's fort.[29]

The vaulted ceiling of the dining hall's corridor closely resembles that of the first-floor corridor in the fort. Additionally, the semi-spherical domes that cover the ceiling of the dining hall are similar to the domes found over the double row of rooms on the first floor of the fort.[30]

The entrance to the dining hall is located opposite the western door of the Church of St. Bishoy. The hall itself is a long, narrow space measuring 27.5 meters in length and 4.5 meters in width. At the center, there is a stone table with benches on either side for the monks to sit. At the northern end of the dining hall, a square room serves as a kitchen for the dining area.[31]

The fence

[edit]

The original walls of the monastery date back to the 9th century, while most of the current walls were constructed in the 11th century, with various sections restored and rebuilt over time. On the western side of the wall, there is a noticeable lack of reinforcement, and the southern two-thirds of the wall have not undergone restoration efforts.[32]

The average height of the walls is approximately ten meters, with a thickness of about two meters. Constructed from limestone, the walls are covered with a layer of plaster.

The entrance to the monastery leads to a corridor featuring a semi-barrel vault that extends into the interior, passing through the "guardhouse" opposite the interior face of the wall. This structure serves as a complete example of similar buildings that exist in the other three monasteries of Wadi Natrun. The ground floor of this building consists of two rooms, one on each side of the entrance corridor. The western room is topped with a dome that covers most of its ceiling, while the northern end features a semi-cylindrical vault. Additionally, a rectangular room is located above the eastern room.[33]

Fortress

[edit]

The current fortress of the Monastery of Saint Pishoy dates back to the late 11th century, constructed after the Berber raid in 1096 that destroyed the earlier structure. This earlier fortress was reportedly commissioned by the Roman Emperor Xenon in the 5th century after learning that his daughter,[34] Princess Ilaria, had fled his palace to seek refuge there as a nun.[35]

Architecturally, the fortress shares similarities with the fortress of the Monastery of Saint Macarius, albeit with some minor variations. The structure consists of a ground floor and one upper level, suggesting that a second upper floor once existed but has since collapsed. A drawbridge connects the fortress, with one end resting against the northern wall of the first floor and the other end on the roof of the guardhouse, leading to the stairs of an adjacent building. This drawbridge could be raised to secure the monks inside during attacks.[36]

The first floor of the fortress features an entrance corridor, with a hall to the east comprising six units covered by domes supported by piers. This hall contains a sanctuary and three altars; however, the curtain that once separated the sanctuary has been removed and relocated to the northern altar of the Church of Saint Pishoy, and the three altars have been dismantled, ceasing prayers in this area. It is believed that this floor may have originally housed the monastery's library.[37]

The second floor has partially collapsed, leaving only the "Church of Archangel Michael," which continues to host prayers. [38]This church was restored by Pope John XIX in 1935, as indicated by an inscription on its eastern wall.[39]

Churches

[edit]The monastery has five churches, namely: St. Pishoy Church, St. Benjamin II Church, St. Girgis Church, Martyr Abaskhiron Church, and the Angel Michael Church in the monastery's fortress.[40]

St. Pishoy church

[edit]

The main church of the Monastery of Saint Pishoy, recognized as the largest church in Wadi al-Natroun, has no remaining traces of the original structure that likely occupied the site. This current church was reconstructed in the 9th century following the fifth Berber raid on the monastery and incorporates numerous architectural elements from various historical periods. While the main sanctuary dates back to the 6th or 7th century, features such as the high domes, stained glass, plaster decorations, and the nave's design likely originate from the 10th or 11th century. Additional modifications were made at the end of the 11th century and the beginning of the 12th century.[41]

In 1330, during the papacy of Benjamin II, the church underwent repairs due to damage inflicted by termites on the wooden structures. Architecturally, the church is characterized by a long design that adheres to basilica-style elements, comprising a nave, two side aisles, a circular western wing, a transverse choir, and three altars. Over time, it evolved into an irregular quadrilateral structure through the addition of small churches and extensions.

In the late 11th and early 12th centuries, the Church of Abu Sukhairoun was constructed on the southern side of the main church, with its northwestern corner adjacent to the southern wall of the 9th-century structure.[42]

St. Benjamin II church

[edit]

The church, named after Pope Benjamin II (number 82), is also known as the Church of the Mary, mother of Jesus. It is situated adjacent to the Church of Saint Pishoy, specifically at the corner formed by the northern walls of the northern altar and the choir of the main church, alongside the eastern wall of the northern deacon's room.

This church features a half-barrel vault and houses the reliquary of Saint Pishoy. The altar area is distinguished by a dome supported by smaller vaults, and within the altar, there is an altar table that is isolated on three sides, resembling the altars found in the main church.[43]

St. Girgis church

[edit]The church, named after Saint George the Roman, dates back to the 11th or 12th century. Currently, it serves primarily as a storage area and replaced an earlier structure that collapsed at an unknown time.

The eastern end of the church is divided by a wall partition into two altars, each covered by a small dome. Both altars feature a rectangular marble slab situated above the altar table.[44]

Martyr Abaskhiron church

[edit]This church, named after Saint Abascheron the Qalini, was founded in the 9th century. It is currently divided into a nave and a chancel, separated by a wooden partition, and features a single semicircular sanctuary adorned with a simple veil. The body of the church is topped with a semicircular dome, supported by small arches, dating back to the 14th century.[45]

The sanctuary lacks an altar platform, but the altar is covered with a rectangular marble slab. [46]A small door to the north of the sanctuary opens into a narrow corridor with a barrel vault that leads to the baptismal chamber. In the 14th century, when the southern sanctuary of the Church of Saint Bishoy was rebuilt, the northern sanctuary of the Church of Abascheron was demolished. As a result, the semicircular sanctuary was constructed in the location of the chancel, and the eastern sanctuary was converted into a baptismal room.[47]

Angel Michael church

[edit]This church is dedicated to Archangel Michael and is situated on the roof of the monastery's fort. Its structure features a half-barrel vault, creating an open and spacious interior. The church contains a single sanctuary, which is crowned by a low dome supported by small arches. Notably, the sanctuary's veil, dating back to 1782, is 242 years old, adding historical to this sacred space.[48]

-

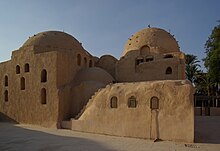

General view of the monastery.

-

Anba Bishoy Cathedral.

-

One of the gates of the cathedral attached to the monastery.

Photos gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The Retreat House at Anba Bishoy Monastery, Wadi al-Natrun. Anba Takla Himanot Abyssinian Church, Alexandria. Archived June 30, 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Somers Clark, Coptic Monuments in the Nile Valley - A Study in Ancient Churches, Translated by: Ibrahim Salama Ibrahim, Egyptian Book Authority, Cairo, 2010: Ibrahim Salama Ibrahim, Egyptian General Book Organization, Cairo, 2010, pp: 292-293.

- ^ Monastery | Monasteries. Church of the Abyssinian Abyssinian priest, Alexandria. Archived July 10, 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Egypt provided the entire Christian world with the foundations and systems of monasticism, says English orientalist. Al-Ahram newspaper, August 14, 2011. Archived May 11, 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ History of the monastery. The official website of the Monastery of the Great Saint Anba Bishoy in Wadi al-Natrun. Archived September 28, 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Pope Shenouda visits the abbot of Anba Bishoy monastery in Al-Salam hospital, Al-Youm Al-Sabea newspaper, June 14, 2011. “Archived copy”. Archived from the original on 2020-03-12. Accessed on 2020-09-16.

- ^ Religious Tourism / Religious Monuments in Beheira. Kenana Online. Archived August 14, 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Pope Shenouda retreats to Anba Bishoy Monastery to protest the “kidnapping” of Christian women. Al-Arabiya. Archived August 01, 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The Great St. Bishoy. Coptic Monasteries Network. Archived February 19, 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Mounir Shoukry, The Monasteries of Wadi al-Natroun, Mar Mina al-Ajabi Society, Alexandria, no date, p: 10.

- ^ Hijaji Ibrahim Mohammed, Introduction to Coptic Defense Architecture, Nahdet al-Sharq Library, Giza, 1984, pp: 106.

- ^ History of the monastery. The official website of the Monastery of the Great Saint Anba Bishoy. Archived September 28, 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Mark Smika, Guide to the Coptic Museum and the Most Important Egyptian Churches and Monasteries, c: 2, Cairo, 1932, p: 89.

- ^ Samuel Tawadros al-Syrian, The Egyptian Monasteries, first edition, 1968, p: 121.

- ^ Nevin Abdel Gawad, The Monasteries of Wadi al-Natroun: An Archaeological and Tourism Study, Egyptian General Book Organization, Cairo, 2007, p: 64.

- ^ Chrismation work. The official website of the Monastery of the Great St. Bishoy. Archived June 24, 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Marcus Simaika, op. cit. 2, p: 89.

- ^ Omar Tosun, Wadi al-Natrun, its monks and monasteries, and a brief history of the patriarchs, Egyptian General Book Organization, Cairo, 2009, p: 191.

- ^ Monastery of the Great Saint Anba Bishoy. Coptic Monasteries Network in Egypt. Archived February 19, 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Omar Tosun, op. cit: 195.

- ^ Anba Samuel and Badie Habib, Ancient Churches and Monasteries of the Sea Face, Cairo and Sinai, Institute of Coptic Studies, Cairo, 1995, pp: 14.

- ^ Samuel Tawadros al-Syrian, op. cit: 76.

- ^ Naim El-Baz, Christ in Egypt - The Journey of the Holy Family, Egyptian General Book Organization, Cairo, 2007, p: 24.

- ^ Samuel Tawadros al-Syrian, op. cit: 128-130.

- ^ Nevin Abdel Gawad, op. cit: 126.

- ^ Anba Bishoy Monastery. Kanshirin Encyclopedia of Churches and Monasteries. Archived March 06, 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ History of the monastery. The official website of the Monastery of the Great Saint Anba Bishoy. Archived September 28, 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Evelyn White, History of the Monasteries of Nitria and Ischia c: 3, translated by: Paula Al-Barmoussi, Cairo, first edition, 1997, p: 146

- ^ Nevin Abdel Gawad, op. cit: 126-127.

- ^ Evelyn White, op. cit: 164.

- ^ Marcus Simaika, op. cit: 2, p: 90.

- ^ Evelyn White, op. cit: 138.

- ^ Nevin Abdel Gawad, op. cit: 257.

- ^ The treasures of Coptic monuments in Egypt's deserts and valleys The history of Christianity in Egypt. Al-Shaab newspaper, July 30, 2011. Archived November 23, 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Omar Tosun, op. cit: 194.

- ^ A.J. Butler, The Ancient Coptic Churches of Egypt c: 1, translated by: Ibrahim Salama Ibrahim, Egyptian General Book Organization, Cairo, 1993, pp. 262.

- ^ Samuel Tawadros al-Syrian, op. cit: 127.

- ^ Anba Bishoy Monastery. Kanshirin Encyclopedia of Churches and Monasteries. Archived March 06, 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Omar Tosun, op. cit: 191.

- ^ Omar Tosun, op. cit: 192.

- ^ A.J. Butler, J. 1, op. cit: 263.

- ^ Evelyn White, op. cit: 142-144.

- ^ A.J. Butler, J. 1, op. cit: 261.

- ^ Nevin Abdel Gawad, op. cit: 136.

- ^ Evelyn White, op. cit. 159.

- ^ Nevin Abdel Gawad, op. cit: 138.

- ^ A.J. Butler, J: 1, op. cit: 262.

- ^ Omar Tosun, op. cit: 193.