Content moderation

On websites that allow users to create content, content moderation is the process of detecting contributions that are irrelevant, obscene, illegal, harmful, or insulting, in contrast to useful or informative contributions, frequently for censorship or suppression of opposing viewpoints. The purpose of content moderation is to remove or apply a warning label to problematic content or allow users to block and filter content themselves.[1]

Various types of Internet sites permit user-generated content such as posts, comments, videos including Internet forums, blogs, and news sites powered by scripts such as phpBB, a Wiki, or PHP-Nuke etc. Depending on the site's content and intended audience, the site's administrators will decide what kinds of user comments are appropriate, then delegate the responsibility of sifting through comments to lesser moderators. Most often, they will attempt to eliminate trolling, spamming, or flaming, although this varies widely from site to site.

Major platforms use a combination of algorithmic tools, user reporting and human review.[1] Social media sites may also employ content moderators to manually flag or remove content flagged for hate speech or other objectionable content. Other content issues include revenge porn, graphic content, child abuse material and propaganda.[1] Some websites must also make their content hospitable to advertisements.[1]

In the United States, content moderation is governed by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, and has seen several cases concerning the issue make it to the United States Supreme Court, such as the current Moody v. NetChoice, LLC.

Supervisor moderation

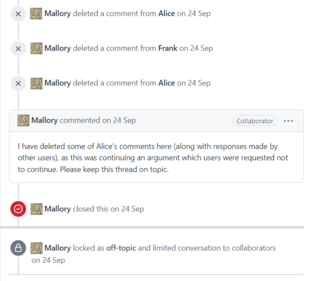

[edit]Also known as unilateral moderation, this kind of moderation system is often seen on Internet forums. A group of people are chosen by the site's administrators (usually on a long-term basis) to act as delegates, enforcing the community rules on their behalf. These moderators are given special privileges to delete or edit others' contributions and/or exclude people based on their e-mail address or IP address, and generally attempt to remove negative contributions throughout the community.[2]

Commercial content moderation

[edit]Commercial Content Moderation is a term coined by Sarah T. Roberts to describe the practice of "monitoring and vetting user-generated content (UGC) for social media platforms of all types, in order to ensure that the content complies with legal and regulatory exigencies, site/community guidelines, user agreements, and that it falls within norms of taste and acceptability for that site and its cultural context."[3]

Industrial composition

[edit]The content moderation industry is estimated to be worth US$9 billion. While no official numbers are provided, there are an estimates 10,000 content moderators for TikTok; 15,000 for Facebook and 1,500 for Twitter as of 2022.[4]

The global value chain of content moderation typically includes social media platforms, large MNE firms and the content moderation suppliers. The social media platforms (e.g Facebook, Google) are largely based in the United States, Europe and China. The MNEs (e.g Accenture, Foiwe) are usually headquartered in the global north or India while suppliers of content moderation are largely located in global southern countries like India and the Philippines.[5]: 79–81

While at one time this work may have been done by volunteers within the online community, for commercial websites this is largely achieved through outsourcing the task to specialized companies, often in low-wage areas such as India and the Philippines. Outsourcing of content moderation jobs grew as a result of the social media boom. With the overwhelming growth of users and UGC, companies needed many more employees to moderate the content. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, tech companies began to outsource jobs to foreign countries that had an educated workforce but were willing to work for cheap.[6]

Working conditions

[edit]Employees work by viewing, assessing and deleting disturbing content.[7] Wired reported in 2014, they may suffer psychological damage[8][9][10][2][11] In 2017, the Guardian reported secondary trauma may arise, with symptoms similar to PTSD.[12] Some large companies such as Facebook offer psychological support[12] and increasingly rely on the use of artificial intelligence to sort out the most graphic and inappropriate content, but critics claim that it is insufficient.[13] In 2019, NPR called it a job hazard.[14] Non-disclosure agreements are the norm when content moderators are hired. This makes moderators more hesitant to speak up about working conditions or organize.[4]

Psychological hazards including stress and post-traumatic stress disorder, combined with the precarity of algorithmic management and low wages make content moderation extremely challenging.[15]: 123 The number of tasks completed, for example labeling content as copyright violation, deleting a post containing hate-speech or reviewing graphic content are quantified for performance and quality assurance.[4]

In February 2019, an investigative report by The Verge described poor working conditions at Cognizant's office in Phoenix, Arizona.[16] Cognizant employees tasked with content moderation for Facebook developed mental health issues, including post-traumatic stress disorder, as a result of exposure to graphic violence, hate speech, and conspiracy theories in the videos they were instructed to evaluate.[16][17] Moderators at the Phoenix office reported drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and sexual intercourse in the workplace, and feared retaliation from terminated workers who threatened to harm them.[16][18] In response, a Cognizant representative stated the company would examine the issues in the report.[16]

The Verge published a follow-up investigation of Cognizant's Tampa, Florida, office in June 2019.[19][20] Employees in the Tampa location described working conditions that were worse than the conditions in the Phoenix office.[19][21][22]

Moderators were required to sign non-disclosure agreements with Cognizant to obtain the job, although three former workers broke the agreements to provide information to The Verge.[19][23] In the Tampa office, workers reported inadequate mental health resources.[19][24] As a result of exposure to videos depicting graphic violence, animal abuse, and child sexual abuse, some employees developed psychological trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder.[19][25] In response to negative coverage related to its content moderation contracts, a Facebook director indicated that Facebook is in the process of developing a "global resiliency team" that would assist its contractors.[19]

Facebook had increased the number of content moderators from 4,500 to 7,500 in 2017 due to legal requirements and other controversies. In Germany, Facebook was responsible for removing hate speech within 24 hours of when it was posted.[26] In late 2018, Facebook created an oversight board or an internal "Supreme Court" to decide what content remains and what content is removed.[14]

According to Frances Haugen, the number of Facebook employees responsible for content moderation was much smaller as of 2021.[27]

Social media site Twitter has a suspension policy. Between August 2015 and December 2017, it suspended over 1.2 million accounts for terrorist content to reduce the number of followers and amount of content associated with the Islamic State.[28] Following the acquisition of Twitter by Elon Musk in October 2022, content rules have been weakened across the platform in an attempt to prioritize free speech.[29] However, the effects of this campaign have been called into question.[30][31]

Distributed moderation

[edit]User moderation

[edit]User moderation allows any user to moderate any other user's contributions. Billions of people are currently making decisions on what to share, forward or give visibility to on a daily basis.[32] On a large site with a sufficiently large active population, this usually works well, since relatively small numbers of troublemakers are screened out by the votes of the rest of the community.

User moderation can also be characterized by reactive moderation. This type of moderation depends on users of a platform or site to report content that is inappropriate and breaches community standards. In this process, when users are faced with an image or video they deem unfit, they can click the report button. The complaint is filed and queued for moderators to look at.[33]

Unionization

[edit]150 content moderators, who contracted for Meta, ByteDance and OpenAI gathered in Nairobi, Kenya to launch the first African Content Moderators Union on 1 May 2023. This union was launched 4 years after Daniel Motaung was fired and retaliated against for organizing a union at Sama, which contracts for Facebook.[34]

See also

[edit]- Like button

- Meta-moderation system

- Moody v. NetChoice, LLC

- Recommender system

- Trust metric

- We Had to Remove This Post

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Grygiel, Jennifer; Brown, Nina (June 2019). "Are social media companies motivated to be good corporate citizens? Examination of the connection between corporate social responsibility and social media safety". Telecommunications Policy. 43 (5): 2, 3. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2018.12.003. S2CID 158295433. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Invisible Data Janitors Mop Up Top Websites - Al Jazeera America". aljazeera.com.

- ^ "Behind the Screen: Commercial Content Moderation (CCM)". Sarah T. Roberts | The Illusion of Volition. 2012-06-20. Retrieved 2017-02-03.

- ^ a b c Wamai, Jacqueline Wambui; Kalume, Maureen Chadi; Gachuki, Monicah; Mukami, Agnes (2023). "A new social contract for the social media platforms: prioritizing rights and working conditions for content creators and moderators | International Labour Organization". International Journal of Labour Research. 12 (1–2). International Labour Organization. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ Ahmad, Sana; Krzywdzinski, Martin (2022), Graham, Mark; Ferrari, Fabian (eds.), "Moderating in Obscurity: How Indian Content Moderators Work in Global Content Moderation Value Chains", Digital Work in the Planetary Market, MIT Press, pp. 77–95, ISBN 978-0-262-36982-4, retrieved 2024-07-22

- ^ Elliott, Vittoria; Parmar, Tekendra (22 July 2020). ""The darkness and despair of people will get to you"". rest of world.

- ^ Stone, Brad (July 18, 2010). "Concern for Those Who Screen the Web for Barbarity". The New York Times.

- ^ Adrian Chen (23 October 2014). "The Laborers Who Keep Dick Pics and Beheadings Out of Your Facebook Feed". WIRED. Archived from the original on 2015-09-13.

- ^ "The Internet's Invisible Sin-Eaters". The Awl. Archived from the original on 2015-09-08.

- ^ "Professor uncovers the Internet's hidden labour force". Western News. March 19, 2014.

- ^ "Should Facebook Block Offensive Videos Before They Post?". WIRED. 26 August 2015.

- ^ a b Olivia Solon (2017-05-04). "Facebook is hiring moderators. But is the job too gruesome to handle?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ Olivia Solon (2017-05-25). "Underpaid and overburdened: the life of a Facebook moderator". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ a b Gross, Terry. "For Facebook Content Moderators, Traumatizing Material Is A Job Hazard". NPR.org.

- ^ Gillespie, Tarleton (2018). Custodians of the internet: platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media (PDF). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-23502-9.

- ^ a b c d Newton, Casey (25 February 2019). "The secret lives of Facebook moderators in America". The Verge. Archived from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (25 February 2019). "Facebook content reviewers are coping with PTSD symptoms by having sex and doing drugs at work, report says". CNBC. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Silverstein, Jason (25 February 2019). "Facebook vows to improve content reviewing after moderators say they suffered PTSD". CBS News. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Newton, Casey (19 June 2019). "Three Facebook moderators break their NDAs to expose a company in crisis". The Verge. Archived from the original on 12 September 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Bridge, Mark (20 June 2019). "Facebook worker who died of heart attack was under 'unworldly' pressure". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Carbone, Christopher (20 June 2019). "Facebook moderator dies after viewing horrific videos, others share disturbing incidents: report". Fox News. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ Eadicicco, Lisa (19 June 2019). "A Facebook content moderator died after suffering heart attack on the job". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on 30 November 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (19 June 2019). "Facebook content moderators break NDAs to expose shocking working conditions involving gruesome videos and feces smeared on walls". CNBC. Archived from the original on 19 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Johnson, O’Ryan (19 June 2019). "Cognizant Getting $200M From Facebook To Moderate Violent Content Amid Allegations Of 'Filthy' Work Conditions: Report". CRN. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Bufkin, Ellie (19 June 2019). "Report reveals desperate working conditions of Facebook moderators — including death". Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Artificial intelligence will create new kinds of work". The Economist. Retrieved 2017-09-02.

- ^ Böhmermann, Jan (2021-12-10). Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen talks about the Facebook Papers. de:ZDF Magazin Royale.

- ^ Gartenstein-Ross, Daveed; Koduvayur, Varsha (26 May 2022). "Texas's New Social Media Law Will Create a Haven for Global Extremists". foreignpolicy.com. Foreign Policy. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ "Elon Musk on X: "@essagar Suspending the Twitter account of a major news organization for publishing a truthful story was obviously incredibly inappropriate"". Twitter. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ^ Burel, Grégoire; Alani, Harith; Farrell, Tracie (2022-05-12). "Elon Musk could roll back social media moderation – just as we're learning how it can stop misinformation". The Conversation. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ^ Fung, Brian (June 2, 2023). "Twitter loses its top content moderation official at a key moment". CNN News.

- ^ Hartmann, Ivar A. (April 2020). "A new framework for online content moderation". Computer Law & Security Review. 36: 3. doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2019.105376. S2CID 209063940. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Grimes-Viort, Blaise (December 7, 2010). "6 types of content moderation you need to know about". Social Media Today.

- ^ Perrigo, Billy (2023-05-01). "150 AI Workers Vote to Unionize at Nairobi Meeting". Time. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

Further reading

[edit]- Sarah T. Roberts (2019). Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300235883.

- Alhoori, Hamed; Alvarez, Omar; Furuta, Richard; Muñiz, Miguel; Urbina, Eduardo (2009), "Supporting the Creation of Scholarly Bibliographies by Communities through Online Reputation Based Social Collaboration", Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries, vol. 5714, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 180–191, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-04346-8_19, ISBN 978-3-642-04345-1, retrieved 2024-07-24

External links

[edit]- Data Workers' Inquiry a collaboration between Weizenbaum Institute, Technische Universität Berlin and DAIR

- Cliff Lampe and Paul Resnick : Slash (dot) and burn: distributed moderation in a large online conversation space Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems table of contents, Vienna, Austria 2005, 543–550.