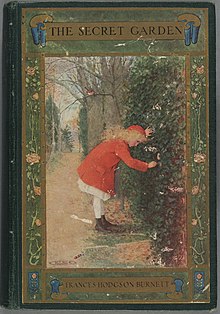

The Secret Garden

Front cover of the US edition | |

| Author | Frances Hodgson Burnett |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | M. L. Kirk (US) Charles Robinson (UK)[1] |

| Genre | Children's novel |

| Publisher | Frederick A. Stokes (US) William Heinemann (UK)[2] |

Publication date | 1911 (UK[2] & US[1]) |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 375 (UK[2] & US[3]) |

| LC Class | PZ7.B934 Se 1911[3] |

| Text | The Secret Garden at Wikisource |

The Secret Garden is a children's novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett first published in book form in 1911, after serialisation in The American Magazine (November 1910 – August 1911). Set in England, it is seen as a classic of English children's literature. The American edition was published by the Frederick A. Stokes Company with illustrations by Maria Louise Kirk (signed as M. L. Kirk) and the British edition by Heinemann with illustrations by Charles Heath Robinson.[1][4]

Several stage and film adaptations have been made of The Secret Garden.

Plot summary

[edit]

At the turn of the 20th century, Mary Lennox is a neglected and unloved 10-year-old girl, born in British India to wealthy British parents who never wanted her and made an effort to ignore her. She is cared for primarily by native servants, who spoil her and allow her to have free rein. After a cholera epidemic kills Mary's parents, the few surviving servants flee the house without Mary.

She is discovered by British soldiers who place her in the temporary care of an English clergyman, whose children taunt her by calling her "Mistress Mary, quite contrary". She is soon sent to England to live with her uncle, Archibald Craven, whom her father's sister Lilias married. He lives on the Yorkshire Moors in a large English country house, Misselthwaite Manor. When escorted to Misselthwaite by the housekeeper Mrs. Medlock, she discovers Lilias Craven is dead and that Mr. Craven is a hunchback.

At first, Mary is as angry and contrary as she was before she was sent there. She dislikes her new home, the people living in it and, most of all, the bleak moor on which it sits. Over time, she becomes more spirited and less cantankerous and befriends her maid, Martha Sowerby, who tells Mary about Lilias Craven, who would spend hours in a private walled garden growing roses. Lilias Craven died after an accident in the garden ten years previously, and the devastated Archibald locked the garden and buried the key.

Mary becomes interested in finding the secret hidden garden herself, and her ill manners begin to soften as a result. Soon, she comes to enjoy the company of Martha, the gardener Ben Weatherstaff, and a friendly robin redbreast. Her health and attitude improve with the bracing Yorkshire air, and she grows stronger as she explores the estate gardens. Mary wonders about the secret garden and about mysterious cries that echo through the house at night.

As Mary explores the gardens, the robin draws her attention to an area of disturbed soil. Here, Mary finds the key to the locked garden, and eventually discovers the door to the garden. She asks Martha for garden tools, which Martha sends with Dickon, her 12-year-old brother, who spends most of his time out on the moors. Mary and Dickon take a liking to each other, as Dickon has a kind way with animals and a good nature. Eager to absorb his gardening knowledge, Mary tells him about the secret garden.

One night, Mary hears the cries once more and decides to follow them through the house. She is startled to find a boy of her age named Colin, who lives in a hidden bedroom. She soon discovers that they are cousins—Colin being the son of Archibald Craven—and that he suffers from fevers and an unspecified spinal condition which precludes him from walking and causes him to be confined to bed. He, like Mary, has grown very spoiled, with servants obeying his every whim in order to prevent the frightening hysterical temper tantrums into which Colin occasionally flies. Mary visits him every day that week, distracting him from his troubles and despondency with stories of the moor, Dickon and his animals, and the secret garden. Mary eventually confides to Colin that she has access to the secret garden, and he asks to see it. Colin is put into his wheelchair and brought outside into the secret garden. It is the first time he has been outdoors for several years. With Mary and Dickon's help and encouragement, and absorbing the beneficial effects of the growing garden, he begins to open up to the world around him and finds renewed hope for his future.

While in the garden, the children look up to see Ben Weatherstaff looking over the wall on a ladder. Startled to find the children in the secret garden, he admits that he believed Colin to be "a cripple." Angry at being called "crippled," Colin rises shakily from his chair and finds that he can stand on his legs, albeit they are weak from long disuse. Mary and Dickon spend almost every day in the garden with Colin, and continue to encourage him to grow stronger and attempt walking. Together, the children and Ben conspire to keep Colin's recovering health a secret from the other staff to surprise his father, who is travelling abroad.

While his son's health improves, Archibald experiences a coinciding increase in spirits, culminating in a dream where his late wife calls to him from inside the garden. When he receives a letter from Mrs. Sowerby, who advises him to come back to Misselthwaite, he takes the opportunity to finally return home. He walks the outer garden wall in his wife's memory, and hears voices inside. He finds the door unlocked and is shocked to see the garden in full bloom and his son restored to health, having just won a race against Mary. The children tell him the entire story, explaining the restoration of both the garden and Colin. Archibald and Colin then walk back to the manor together, observed by the stunned and incredulous servants.

Themes

[edit]In his analysis of the narrative structures of "the traditional novel for girls", Perry Nodelman highlights Mary Lennox as a departure from the narrative pattern of the "spontaneous and ebullient" orphan girl who changes her new home and family for the better, since those qualities appear later on in the narrative. The revival of the family and the home in these novels, according to Nodelman, "is carried to the extreme in The Secret Garden," in which the garden's restoration and the arrival of spring parallel the emergence of human characters from the home, "almost as if they had been hibernating".[5] Joe Sutliff Sanders examines Mary and The Secret Garden within the context of the Victorian and Edwardian cultural debate over affective discipline, which was echoed in contemporary books about orphan girls. He suggests that The Secret Garden was interested in showing the benefits of affective discipline for men and boys, namely Colin who learns from Mary, understood as "the novel's representative of girlhood" and how to wield his "masculine privilege".[6]

The titular garden has been the subject of much scholarly discussion. Phyllis Bixler Koppes writes that The Secret Garden makes use of the fairy tale, the exemplum, and the pastoral literary genres, which lends the novel a deeper "thematic development and symbolic resonance" than Burnett's earlier children's novels which only used elements from the first two traditions.[7] She describes the garden as "the central georgic trope, the unifying symbol of rebirth in Burnett's novel".[8] Madelon S. Gohlke understands the titular garden as "both the scene of a tragedy, resulting in the near destruction of a family", as well as the site of its regeneration and restoration.[9]

Alexandra Valint suggests that most of the novel's depictions of disability coincide with the stereotypical view of people with disabilities as unhappy, helpless, and less independent than people without disabilities. Colin's use of a wheelchair would have been understood by Edwardian readers as a marker of both disability and social status.[10]

Elizabeth Lennox Keyser writes that The Secret Garden is ambivalent about sex roles: while Mary restores the garden and saves the family, her role in the story is overshadowed at the conclusion of the novel by the return of Colin and his father, which may be seen as a defense of patriarchal authority.[11] Danielle E. Price notes that the novel deals with "the thorny issues of sex, class, and imperialism".[12] She writes how Mary's development in the novel parallels "the steps of nineteenth-century garden theorists in their plans for the perfect garden", with Mary ultimately turning into "a girl who, like the ideal garden, can provide both beauty and comfort, and who can cultivate her male cousin, the young patriarch-in-training".[12]

In his examination of The Secret Garden within the context of postcolonialism, Jerry Phillips writes that the novel "is not so much a discourse on the end of empire as an embryonic commentary on the possibility of blowback".[13]

Background

[edit]

At the time Burnett began working on The Secret Garden, she had already established a literary reputation as a writer of children's fiction and social realist adult fiction.[14] She had started writing children's fiction in the 1880s, with her most notable book at the time being her sentimental novel Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886).[15] Little Lord Fauntleroy was a "literary sensation" in both the United States and Europe, and sold hundreds of thousands of copies.[14] Prior to The Secret Garden, she had also written another notable work of children's fiction, A Little Princess (1905), which had begun as a story published in the American children's magazine St. Nicholas Magazine in 1887 and was later adapted as a play in 1902.[16]

Little is known about the literary development and conception of The Secret Garden.[17] Biographers and other scholars have been able to glean the details of Burnett's process and thoughts on her other books through her letters to family members; during the time she was working on The Secret Garden, however, she was living near to them and thus did not need to send them letters.[17] Burnett started the novel in spring 1909, as she was making plans for the garden at her home in Plandome on Long Island.[18] In an October 1910 letter to William Heinemann, her publisher in England, she described the story, whose working title was Mistress Mary, as "an innocent thriller of a story" that she considered "one of [her] best finds".[19] Biographer Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina offers several explanations as to why there is so little surviving information on the book's development. Firstly, Burnett's health faltered after moving to her home in Plandome, and her social excursions became limited as a result. Secondly, her existing notes about The Secret Garden, along with a portrait of her and some photographs, were donated by her son Vivian after her death to a lower Manhattan public school serving the deaf in remembrance of her visit there years previously, but all the items soon vanished from the archive of the school. Lastly, a few weeks before the novel's publication, her brother-in-law died in a collision with a trolley, an event that likely darkened the novel's publication.[20]

Burnett's story My Robin, however, offers a glimpse of the creation of The Secret Garden.[21] In it, she addresses a reader's question on the literary origins of the robin that appears in The Secret Garden, whom the reader felt "could not have been a mere creature of fantasy".[22] Burnett reminisces on her friendship with the real-life English robin, whom she described as "a person—not a mere bird" and who often kept her company in the rose garden where she would often write, when she lived at Maytham Hall.[22] Recounting the first time she tried to communicate with the bird via "low, soft, little sounds", she writes that she "knew—years later—that this is what Mistress Mary thought when she bent down in the Long Walk and 'tried to make robin sounds'".[23]

Maytham Hall in Kent, England, where Burnett lived for a number of years during her marriage, is often cited as the inspiration for the book's setting.[24] Biographer Ann Thwaite writes that while the rose garden at Mayham Hall may have been "crucial" to the novel's development, Maytham Hall and Misselthwaite Manor are physically very different.[24] Thwaite suggests that, for the setting of The Secret Garden, Burnett may have been inspired by the moors of Emily Brontë's 1847 novel Wuthering Heights, given that Burnett only went once to Yorkshire, to Fryston Hall.[25] She writes that Burnett may have also taken inspiration from Charlotte Brontë's 1847 novel Jane Eyre, noting parallels between the two narratives: both of them, for example, feature orphans sent to "mysterious mansions", whose master is largely absent.[26] Burnett herself was aware of the similarities, remarking in a letter that Ella Hepworth Dixon had described it as a children's version of Jane Eyre.[19]

Scholar Gretchen V. Rector has examined the author's manuscript of The Secret Garden, which she describes as "the only record of the novel's development".[27] Eighty of the first hundred pages of the manuscript are written in black ink, while the rest and subsequent revisions were made in pencil; the spelling and punctuation tend to follow the American standard. Chapter headings were included prior to the novel's serialization and are not present in the manuscript, with chapters in it delineated by numbers only.[28] The pagination of the manuscript was likely done by a second person: it goes from 1 to 234, only to restart at the nineteenth chapter.[28] From the title page, Rector surmises that the novel's first title was Mary, Mary quite Contrary, later changed to its working title of Mistress Mary.[27] Mary herself is originally nine in the manuscript, only to be aged up a year in a revision, perhaps to highlight the "convergent paths" of Mary, Colin, and the garden itself; however, this revision was not reflected in either the British or the American first editions of the novel, or in later editions.[29] Susan Sowerby is initially introduced to the readers as a deceased character, with her daughter Martha perhaps intended to fill her role in the story; Burnett, however, changed her mind about Susan Sowerby, writing her as a living character a few pages later and crossing out the announcement of her death.[30] Additionally, Dickon in the manuscript was physically disabled and used crutches to move around, perhaps drawing on Burnett's recollections of her first husband, Dr. Swan Burnett, and his physical disability. Burnett later removed references to Dickon's disability.[31]

Publication history

[edit]The Secret Garden may be one of the first instances of a story for children first appearing in a magazine with an adult readership,[32] an occasion of which Burnett herself was aware at the time.[19] The Secret Garden was first published in ten issues (November 1910 – August 1911) of The American Magazine, with illustrations by J. Scott Williams.[33] It was first published in book form in August 1911 by the Frederick A. Stokes Company in New York;[34] it was also published that year by William Heinemann in London, illustrated by Charles Robinson. Its copyright expired in the US in 1986,[35] and in most other parts of the world in 1995, placing the book in the public domain. As a result, several abridged and unabridged editions were published in the late 1980s and early 1990s, such as a full-colour illustrated edition from David R. Godine, Publisher in 1989.

Inga Moore's abridged edition of 2008, illustrated by her, is arranged so that a line of the text also serves as a caption to a picture.

Public reception

[edit]Upon its publication in novel format, The Secret Garden garnered largely warm reviews from literary critics,[36][37] and sold well, with a second printing announced within a month after the novel's release.[38] In general, it was seen as an enjoyable novel, and was reviewed within the context of Burnett's previous works, including Little Lord Fauntleroy.[39] It sold well during the 1911 Christmas season, becoming a bestseller in the fiction category, and placing on critical "best of" lists, including that of the Literary Digest and The New York Times.[40] Its literary debut in a magazine for adults led the public to understand it as adult fiction; the book was marketed accordingly, "with some overlap in the juvenile market", which affected its reception by the public.[41] Of this time, scholar Anne Lundin writes that "The Secret Garden struggled to assert its own identity as a different kind of story that spoke to both the romanticism and modernism of a new century".[41] Burnett regarded The Secret Garden as her favorite novel, although she considered one of her novels for adults, In Connection with the DeWilloughby Claim, to be her Great American Novel.[42]

Tracing the book's revival from almost complete eclipse at the time of Burnett's death in 1924, Lundin notes that the author's obituary notices all remarked on Little Lord Fauntleroy and passed over The Secret Garden in silence.[43] Burnett's literary reputation waned over the following decades, possibly as a result of biases towards books that garner a female audience.[44] Despite being largely overlooked by literary critics and librarians,[45] The Secret Garden enjoyed a considerable following among its readers.[36] It continued to rank well on readers' polls for favorite stories. In 1927, it placed in the top fifteen favorite books of female Youth Companion readers, and in the 1960s, the readers of The New York Times ranked The Secret Garden as one of the best children's books. Surveys of adult readers in the 1970s and 1980s show that the novel was a frequent childhood favorite, especially for women.[46]

Burnett's literary reputation underwent a critical resurgence in the 1950s. Marghanita Laski's Mrs Ewing, Mrs Molesworth and Mrs Hodgson Burnett (1951) described The Secret Garden, A Little Princess, and Little Lord Fauntleroy as the best of Burnett's children's books; Laski considered The Secret Garden to be the best of the three, with a capacity to reach thoughtful and self-reflective children.[44] Other British literary critics and historians began to take note of the novel, including Roger Lancelyn Green and John Rowe Townsend.[47] Thwaite's biography about Burnett, Waiting for the Party (1974), highlighted The Secret Garden for its depiction of unpleasant children that she felt was much closer to contemporary ideas about how children behave.[48] At the time that Thwaite's biography was published, children's literature was becoming a field of greater scholarly interest, and as a result, The Secret Garden began to garner more scholarly analysis.[49] The Secret Garden became accepted as part of the scholarly canon of children's literature in the 1980s.[49]

In the twentieth-first century, The Secret Garden continues to be well regarded among readers. In 2003 it ranked No. 51 in The Big Read, a survey of the British public by the BBC to identify the "Nation's Best-loved Novel" (not just children's novel).[50] Based on a 2007 online poll, the U.S. National Education Association listed it as one of "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children".[51][52] In 2012, it was ranked No. 15 among all-time children's novels in a survey published by School Library Journal, a monthly with a primarily US audience.[53] A Little Princess was ranked number 56 and Little Lord Fauntleroy did not make the Top 100.[53] Jeffrey Masson considers The Secret Garden "one of the greatest books ever written for children".[54] In an oblique compliment, Barbara Sleigh has her title character reading The Secret Garden on the train at the beginning of her children's novel Jessamy and Roald Dahl, in his children's book Matilda, has his title character say that she liked The Secret Garden best of all the children's books in the library.[55]

Adaptations

[edit]Film

[edit]

The first motion picture version was made in 1918[56] by the Famous Players–Lasky Corporation, with 14-year-old Lila Lee as Mary and Paul Willis as Dickon. The film is believed lost.

In 1949, MGM filmed the second adaptation, which starred Margaret O'Brien as Mary, Dean Stockwell as Colin and Brian Roper as Dickon. This version was mainly black-and-white, but with all of the sequences set in the garden filmed in Technicolor. Noel Streatfeild's 1948 novel The Painted Garden was inspired by the making of this film.

American Zoetrope's 1993 production was directed by Agnieszka Holland with a screenplay by Caroline Thompson and starred Kate Maberly as Mary, Heydon Prowse as Colin, Andrew Knott as Dickon, John Lynch as Lord Craven and Dame Maggie Smith as Mrs Medlock. The executive producer was Francis Ford Coppola.

A 2017 production by Dogwood Motion Picture Company is available on the BYUtv Network. A science fiction adaptation in the Victorian style, it was filmed, directed and written for the screen by Owen Smith.

The 2020 film version from Heyday Films and StudioCanal is directed by Marc Munden with a screenplay by Jack Thorne.[57]

Television

[edit]Dorothea Brooking adapted the book for BBC television on several occasions;in 1952, 1960 and 1975.[58][59]

Hallmark Hall of Fame filmed a TV movie adaptation of the novel in 1987, which starred Gennie James as Mary, Barret Oliver as Dickon and Jadrien Steele as Colin. Billie Whitelaw appeared as Mrs Medlock and Derek Jacobi played the role of Archibald Craven, with Alison Doody appearing in flashbacks and visions as Lilias; Colin Firth made a brief appearance as the adult Colin Craven. The story was changed slightly. Colin's father, instead of being Mary's uncle, was now an old friend of Mary's father, allowing Colin and Mary to begin a relationship as adults by the film's end. It was filmed at Highclere Castle, which later became known as the filming location for Downton Abbey. It aired on 30 November. In 2001, Hallmark produced a sequel entitled Back to the Secret Garden.

A 1994 animated adaptation as an ABC Weekend Special starred Honor Blackman as Mrs Medlock, Derek Jacobi as Archibald Craven, Glynis Johns as Darjeeling, Victor Spinetti as Dr. Craven, Anndi McAfee as Mary Lennox, Joe Baker as Ben Weatherstaff, Felix Bell as Dickon Sowerby, Naomi Bell as Martha Sowerby, Richard Stuart as Colin Craven and Frank Welker as Robin. This version was produced by Mike Young Productions and DiC Entertainment, and was released on video in 1995 by ABC Video and distributed by Paramount Home Entertainment.[60][61]

In Japan, NHK produced an anime adaptation of the novel in 1991–1992 entitled Anime Himitsu no Hanazono (アニメ ひみつの花園). Miina Tominaga contributed the voice of Mary, while Mayumi Tanaka voiced Colin. The 39-episode TV series was directed by Tameo Kohanawa and written by Kaoru Umeno. This anime is sometimes mistakenly assumed to be related to the popular dorama series Himitsu no Hanazono. It is unavailable in English language, but has been dubbed into several other languages including: Arabic, Spanish, Italian, Polish and Tagalog.

Theatre

[edit]Stage adaptations of the book include a Theatre for Young Audiences version written in 1991 by Pamela Sterling of Arizona State University. This won an American Alliance for Theater and Education "Distinguished New Play" award and is listed in ASSITEH/USA's International Bibliography of Outstanding Plays for Young Audiences.[62]

Multiple musical adaptations have been made. In 1986, there was The Secret Garden: A New Musical with music by Sharon Burgett and Susan Beckwith-Smith, lyrics by Sharon Burgett, Diana Matterson, Susan Beckwith-Smith, Chandler Warren, Will Holt, and book by Alfred Shaughnessy.[63] Another version was released in 1987 with the book and lyrics by Diana Morgan.[64] Thomas W. Olson wrote a version for the Children's Theatre Company in 1988; the play includes music by Hiram Titus, but is not a musical.[65] However, the most well-known and successful musical adaptation is the 1991 Broadway musical with music by Lucy Simon and book and lyrics by Marsha Norman. The production was nominated for seven Tony Awards, winning Best Book of a Musical and Best Featured Actress in a Musical for Daisy Eagan as Mary, then eleven years old.

In 2013, an opera by the American composer Nolan Gasser, which had been commissioned by the San Francisco Opera, was first performed at the Zellerbach Hall at the University of California, Berkeley.

A stage play by Jessica Swale adapted from the novel was performed at Grosvenor Park Open Air Theatre in Chester in 2014.[66]

In 2020, the Scottish family theatre company Red Bridge Arts produced a retelling of the story set in modern-day Scotland, adapted by Rosalind Sydney.[67]

In 2024, Regent's Park Open Air Theatre produced a retelling of the story, adapted by Anna Himali Howard and Holly Robinson.[68]

Radio

[edit]In 1997, Focus On The Family Radio Theatre produced an adaptation in which Joan Plowright narrated as the older Mary Lennox. The cast included Ron Moody as Ben Weatherstaff.[69]

Book forms and sequels

[edit]In 2021, two versions of the story, adapted into graphic novels, were released. The first, released on June 15, was The Secret Garden: A Graphic Novel, with story by Mariah Marsden and illustrations by Hanna Luechtefeld.[70] The second, released on October 19, was a modern retelling by Ivy Noelle Weir, The Secret Garden on 81st Street, following the same vein as the author's previous Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy.[71] A Japanese-language adaptation of the novel was written by Chihiro Kurihara and illustrated by You Shiina and was released in October 2012 through Tsubasa Bunko.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c The Secret Garden title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ a b c "British Library Item details". primocat.bl.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ a b The Secret Garden (first edition). Library of Congress Online Catalog. LCCN Permalink (lccn.loc.gov). Retrieved 24 March 2017. The catalog record reports 4 leaves of plates, 4 color illustrations (uncredited).

- ^ WorldCat library records:

OCLC 1289609, OCLC 317817635 (US); OCLC 8746090 (UK).

Retrieved 24 March 2017. - ^ Nodelman, Perry (1979). "Progressive Utopia: Or; How to Grow Up Without Growing Up". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 1: 146–154. doi:10.1353/chq.1979.0006. S2CID 143452307 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ Sanders 2011, p. 99.

- ^ Koppes 1978, p. 191.

- ^ Koppes 1978, p. 203.

- ^ Gohlke 1980, p. 895.

- ^ Valint 2016, pp. 262–3, 266.

- ^ Keyser 1983, p. 12.

- ^ a b Price 2001, p. 4.

- ^ Phillips 1993, p. 169.

- ^ a b Horne & Sanders 2011, p. xv.

- ^ Bixler 1996, p. 4.

- ^ Bixler 1996, p. 5.

- ^ a b Gerzina 2004, p. 261.

- ^ Thwaite 1974, pp. 219–220.

- ^ a b c Gerzina 2004, p. 262.

- ^ Gerzina 2004, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Gerzina 2004, p. 266.

- ^ a b Burnett 2007, p. 261.

- ^ Burnett 2007, p. 263.

- ^ a b Thwaite 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Thwaite 2006, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Thwaite 1974, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Rector 2006, p. 189.

- ^ a b Rector 2006, p. 187.

- ^ Rector 2006, p. 190.

- ^ Rector 2006, p. 191.

- ^ Rector 2006, pp. 194.

- ^ Gerzina 2007, p. xxxviii.

- ^ "The American Magazine, November 1910". FictionMags Index. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "New York Literary Notes". The New York Times. 16 July 1911. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Lundin 2006, p. 287.

- ^ a b Thwaite 1974, p. 220.

- ^ Bixler 1996, p. 13.

- ^ Lundin 2006, p. 155.

- ^ Lundin 2006, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Lundin 2006, p. 281.

- ^ a b Lundin 2006, p. 279.

- ^ Gerzina 2004, p. 265.

- ^ A. Lundin, Constructing the Canon of Children's Literature: Beyond Library Walls, 133 ff.

- ^ a b Bixler 1996, p. 14.

- ^ Lundin 2006, p. 283.

- ^ Bixler 1996, p. 10.

- ^ Lundin 2006, p. 285.

- ^ Bixler 1996, p. 16.

- ^ a b Bixler 1996, p. 17.

- ^ "BBC – The Big Read". BBC. April 2003, Retrieved 18 October 2012

- ^ National Education Association (2007). "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children". Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "National Education Association's "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children"". List Challenges. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

The following list was compiled from an online survey in 2007. Parents and teachers will find it useful in selecting quality literature for children. —NEA

- ^ a b Bird, Elizabeth (7 July 2012). "Top 100 Chapter Book Poll Results". A Fuse #8 Production. Blog. School Library Journal (blog.schoollibraryjournal.com). Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Masson, Jeffrey Moussaieff (1980). The Oceanic Feeling: The Origins of Religious Sentiment in Ancient India. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel. ISBN 90-277-1050-3.

- ^ Barbara Sleigh: Jessamy (London: Collins, 1967), p. 7 and Roald Dahl: Matilda (London: Jonathan Cape, 1988) (see this extract from Matilda).

- ^ "Lila Lee Is At Present Holidaying In East". The Calgary Albertan. 7 December 1918. p. 15.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (20 January 2018). "Marc Munden To Helm The Secret Garden For David Heyman & Studiocanal". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Barnes, Edward (3 May 1999). "Dorothea Brooking". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Obituary: Dorothea Brooking". The Independent. 5 April 1999. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ ABC Weekend Specials: The Secret Garden (TV episode 1994) at IMDb

- ^ Lynne Heffley (4 November 1994). "TV Review: Animated 'Garden' Wilts on ABC". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "The Secret Garden". Dramatic Publishing. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ The Secret Garden - A New Musical (1994, CD), retrieved 1 December 2021

- ^ The secret garden: a musical, England: [publisher not identified]: Distributed by Dress Circle, 1993, OCLC 29463845, retrieved 16 December 2021

- ^ "The Secret Garden".

- ^ "The Secret Garden". Grosvenor Park Open Air Theatre. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Fisher, Mark (16 February 2020). "The Secret Garden review – grunts and gags in lush retelling". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ "The Secret Garden".

- ^ "Timeless Classics". 31 July 2024.

- ^ The Secret Garden: A Graphic Novel. Andrews McMeel Publishing. 15 June 2021. ISBN 978-1-5248-6964-9.

- ^ Weir, Ivy Noelle (19 October 2021). The Secret Garden on 81st Street: A Modern Graphic Retelling of The Secret Garden. Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-0-316-45968-6.

References

[edit]- Bixler, Phyllis (1996). The Secret Garden: Nature's Magic. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 9780805788150.

- Burnett, Frances Hodgson (2007). "My Robin". In Gretchen Gerzina (ed.). The Annotated Secret Garden. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06029-4.

- Gerzina, Gretchen Holbrook (2004). Frances Hodgson Burnett: The Unexpected Life of the Author of The Secret Garden. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813533827.

- Gerzina, Gretchen, ed. (2007). "Introduction". The Annotated Secret Garden. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06029-4.

- Gohlke, Madelon S. (1980). "Re-Reading the Secret Garden". College English. 41 (8): 894–902. doi:10.2307/376057. JSTOR 376057.

- Horne, Jackie C.; Sanders, Joe Sutliff (2011). "Introduction". Frances Hodgson Burnett's The Secret Garden: A Children's Classic at 100. Children's Literature Association and The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810881877.

- Keyser, Elizabeth Lennox (1983). ""Quite Contrary": Frances Hodgson Burnett's The Secret Garden". Children's Literature. 11. Johns Hopkins University Press: 1–13. doi:10.1353/chl.0.0636.

- Koppes, Phyllis Bixler (1978). "Tradition and the Individual Talent of Frances Hodgson Burnett: A Generic Analysis of Little Lord Fauntleroy, A Little Princess, and The Secret Garden". Children's Literature. 7. Johns Hopkins University Press: 191–207. doi:10.1353/chl.0.0131.

- Lundin, Anne (2006). "The Critical and Commercial Reception of The Secret Garden, 1911-2004". In Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina (ed.). The Secret Garden: Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Contexts, Burnett in the Press, Criticism. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393926354.

- Phillips, Jerry (1993). "The Mem Sahib, the Worthy, the Rajah and His Minions: Some Reflections on the Class Politics of The Secret Garden". The Lion and the Unicorn. 17 (2). Johns Hopkins University Press: 168–194. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0133. S2CID 144237117.

- Price, Danielle E. (2001). "Cultivating Mary: The Victorian Secret Garden". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 26 (1): 4–14. doi:10.1353/chq.0.1658.

- Rector, Gretchen (2006). "The Manuscript of The Secret Garden". In Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina (ed.). The Secret Garden: Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Contexts, Burnett in the Press, Criticism. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393926354.

- Sanders, Joe Sutliff (2011). Disciplining Girls: Understanding the Origins of the Classic Orphan Girl Story. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Thwaite, Ann (1974). Waiting for the Party: The Life of Frances Hodgson Burnett 1849-1924. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Thwaite, Ann (2006). "A Biographer Looks Back". In Angelica Shirley Carpenter (ed.). In the Garden: Essays in Honor of Frances Hodgson Burnett. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5288-4.

- Valint, Alexandra (2016). ""Wheel Me Over There!": Disability and Colin's Wheelchair in The Secret Garden". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 41 (3). Johns Hopkins University Press: 263–280. doi:10.1353/chq.2016.0032.

External links

[edit]- The Secret Garden at Standard Ebooks

- The Secret Garden at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML illustrated)

The Secret Garden public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Secret Garden public domain audiobook at LibriVox- The Secret Garden, available at Internet Archive. New York: F. A. Stokes, 1911 (colour scanned book)

- The Secret Garden From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- The Secret Garden as it appeared in The American Magazine via the Hathi Trust

- 1911 American novels

- 1911 British novels

- 1911 children's books

- American children's novels

- American novels adapted into films

- American novels adapted into plays

- British children's novels

- British novels adapted into films

- British novels adapted into plays

- Disability literature

- Novels by Frances Hodgson Burnett

- Novels first published in serial form

- American novels adapted into television shows

- Works originally published in The American Magazine

- Novels about orphans

- Novels set in Yorkshire

- Children's books set in Yorkshire

- Heinemann (publisher) books

- ABC Weekend Special

- British novels adapted into television shows

- Novels adapted into operas

- Frederick A. Stokes Company books

- Novels about disability