Militia (England)

The English Militia was the principal military reserve force of the Kingdom of England. Militia units were repeatedly raised in England from the Anglo-Saxon period onwards for internal security duties and to defend against external invasions. One of the first militia units in England were the fyrd, which were raised from freemen to defend the estate of their local Shire's lord or accompany the housecarls on offensive expeditions. During the Middle Ages, English militia units continued to be raised for service in various conflicts such as the Wars of Scottish Independence, the Hundred Years' War and the Wars of the Roses. Militia troops continued to see service in Tudor and Stuart periods, most prominently in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Following the Acts of Union 1707, the English Militia was transformed into the British Militia.

Origins

[edit]

The origins of military obligation in England pre-date the establishment of the English state in the 10th century, and can be traced to the 'common burdens' of the Anglo-Saxon period, among which was service in the fyrd, or army. There is evidence that such an obligation existed in the Kingdom of Kent by the end of the 7th century, Mercia in the 8th century and Wessex in the 9th century, and the Burghal Hidage of 911–919 indicates that over 27,000 men could have been raised in the defence of 30 West Saxon boroughs. In the late 10th century, areas began to be divided into 'hundreds' as units for the fyrd. The obligation to serve was placed on landholders, and the Domesday Book indicates that individuals were expected to serve for approximately 60 days.[1]

The Norman conquest of England in 1066 brought with it a feudal system which also contained an element of military obligation in the form of the feudal host. This system supplemented rather than replaced the fyrd, which continued to be deployed until at least the beginning of the 12th century. The Assize of Arms of 1181 combined the two systems by dividing the free population into four categories according to wealth and prescribing the weapons each was to maintain. The first category corresponded to the feudal host, the next two corresponded to the old fyrd and the last to a general levy. The Statute of Winchester in 1285 introduced two more non-feudal categories to impose a general military obligation on all able-bodied males, including non-free, between the ages of 15 and 60, and updated the prescribed weaponry in the light of developments in warfare at the time.[2][3]

Because it was not practical to call out every man, King Edward I introduced a system whereby local gentry were authorised to conduct commissions of array to select those who would actually be called for military service.[4][5] During the reign of King Edward III, feudal service was recognised as increasingly obsolete, and the feudal host was formally called out in full for the last time in 1327. During the Hundred Years' War, the king raised armies for service in France by indenture, which contracted magnates, under their obligation as subjects rather than feudal tenants, to supply a certain number of men for a specific amount of time in return for a set fee. Those forces allocated for the defence of England, however, were raised on the basis of the general obligation[6]

Sixteenth century

[edit]In 1511, King Henry VIII signalled the elevation of the national obligation as the sole means of raising armies from the citizenry. He ordered the commissioners of array be responsible not just for the raising of levies, but also for ensuring that they were suitably equipped according to the Statute of Winchester. He also restricted landowners to raising forces only from their own tenants or others for whom, by the tenure of office, they were responsible. By these means Henry instituted a quasi-feudal system, whereby he looked to the nobility to raise forces, but expected them to do so within the constraints of the shire levies, and the last use of indenture to raise an army came in 1512.[7]

Italian ambassadors reckoned that England had 150,000 armed men in 1519 and 100,000 in 1544 and 1551 available through their militia, while a French ambassador in 1570 reported that 120,000 were ready to serve. This was reasonably close to the truth as 183,000 militiamen were mustered in 37 counties in 1575, and in the officials returns of 1588 more than 132,000 were expected to be fielded in England and Wales. They were intended to comprise part of the armies raised to combat the Spanish invasion. There were expected to be a total of 92,000 men mustered in the south of England (including 5,300 cavalry). Their poor state of readiness and obsolete nature of the weapons they used (mainly bills and longbows) prompted the creation of the more elite Trained Bands, who numbered 50,000 in 1588 (comprising about a third of the militia). This was only a partial solution however. By 1591 official records show 102,000 men on the rolls, of whom 42,000 are fully trained and furnished, plus 54,000 armed but not sufficiently trained and 6,000 neither armed nor trained. In 1588 the Trained Bands primary weapons were 42% firearms, 26% pikes, 18% longbows, and 16% bills.[8]

A 1522 survey had revealed a significant lapse in the obligation to maintain arms and train in their use, and from 1535 commissioners of muster held tri-annual inspections.[9] In the mid-16th century Lords Lieutenant began to be appointed, a great improvement in local authority, and an increasingly efficient machinery for enforcing the obligations of the citizenry to be ready for war resulted in 1558 the Militia Act, which ended the quasi-feudal system and implemented a more efficient, unified national militia system.[10][11] In an attempt to remove the statutory limitations and allow the lieutenants to increase their demands on the militia, the act was repealed in 1604. This, however, succeeded only in removing the statutory basis for the militia itself. Although the militia continued to exist, it fell into neglect as attempts to introduce new legislation to regulate it failed.[12]

English Civil War and the development of a standing army

[edit]

The beginning of the English Civil War was marked by a struggle between King Charles I and Parliament for control of the militia.[13] The indecisive Battle of Edgehill in 1642, the first pitched battle of the war, revealed the weakness of the amateur military system, and both sides struggled with barely trained, poorly-equipped, ill-disciplined and badly led armies.[14] While the Royalists persisted with the amateur tradition, the Parliamentarians developed the New Model Army, a small but disciplined, well-equipped and trained army led by officers selected according to ability rather than birth. The New Model Army defeated the Royalist army at the Battle of Naseby in 1645, effectively ending the First English Civil War in victory for the Parliamentarians.[15]

Following the execution of King Charles I, the establishment of the Commonwealth of England and the subsequent Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell, the New Model Army became politicised, and by the time of Cromwell's death in 1658, martial law and the Rule of the Major-Generals had renewed the traditional mistrust of standing armies.[16] On the restoration of King Charles II to the throne in 1660, the New Model Army was disbanded. Despite the concerns of Parliament about expense and the threat to the power it had only recently won from the Crown, it still proved necessary to maintain a small standing force in England, for the protection of the new king and to garrison coastal forts. A new army was therefore established in 1660, comprising two regiments born in the civil war; one raised in 1656 as Charles's bodyguard while he was in exile during the Interregnum, the other raised in 1650 as part of the New Model Army. Several conspiracies uncovered towards the end of 1660 convinced Parliament of the need for two more regiments – again, one raised in exile during the Interregnum, the other originally a New Model Army regiment – and the army was officially established by royal warrant on 26 January 1661.[17][a]

In the midst of the English Civil War there was some debate as to whether the militia should be a supplement or an alternative to a standing army, and a series of ordinances were passed in attempts to replace the repealed 1558 act. These reflected the ongoing struggle for control of the militia until, in the early 1660s, new legislation established the militia under the control, through the lieutenancy, of the gentry. The legislation made it a counter to the standing army, the main bulwark against disorder and the guarantee of the political settlement.[20]

Militia and the army

[edit]The army – which, by the time of King James II's accession in 1685, comprised seven regiments of foot and four mounted regiments – was officially part of the royal household and had no basis in law; both king and Parliament were careful to refer to the regiments as 'guards', based on their role as bodyguards to the king, and it was still intended that the militia would provide the country's main force in the event of war.[21] However, it was the army, already made more palatable to Parliament by acts of civilian service in support of the common good, that defeated the Monmouth Rebellion in 1685, the militia having proved too slow to mobilise.[22] Following the rebellion, King James II was able to expand the army with 16 new regiments, paid for by money misappropriated from funds voted by Parliament for the militia.[23] The Glorious Revolution of 1688 brought the Dutch King William III to the throne, and with him came interests in continental Europe. It was the defence of these interests that would lead, by the time of the Battle of Blenheim in 1704, to the establishment of the army as an accepted state body and a military leader in Europe.[24] The status of the army as a state institution under parliamentary control and subject to national law was normalised in 1689 by the Bill of Rights and the annually passed Mutiny Acts.[25]

Failure in the Monmouth Rebellion and controversy over the mis-use of funds had an adverse effect on the militia. Although it continued to be called out, for example in the Second Anglo-Dutch War, in the aftermath of the Battle of Beachy Head and in the face of the Jacobite risings, the militia entered a period of decline.[26] In some areas it received at best only 12 days of annual training, and in others it had not been mustered in a generation. It was regarded as so ineffective that against the Jacobite rising of 1745 it would prove more expedient to raise an ad hoc force of volunteers than to rely on the militia.[27]

Militia in the English Empire

[edit]

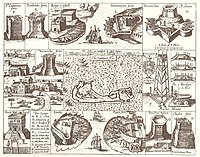

Successful English settlement of North America, where little support could be provided by regular forces, began to take place in 1607, in the face of Spain's determination to prevent England establishing a foothold in territory it claimed for itself. The settlers also had to contend with frequently hostile native populations. It was immediately necessary to raise militia amongst the settlers. The militia in Jamestown saw constant action against the Powhatan Federation and other native polities. In the Virginia Company's other outpost, Bermuda, settled officially in 1612 (unofficially in 1609), the construction of defensive works was placed before all other priorities. A Spanish attack in 1614 was repulsed by two shots fired from the incomplete Castle Islands Fortifications manned by Bermudian Militiamen. In the nineteenth century, Fortress Bermuda would become Britain's Gibraltar of the West, heavily fortified by a Regular Army garrison to protect the Royal Navy's headquarters and dockyard in the Western Atlantic. In the 17th century, however, Bermuda's defence was left entirely in the hands of the Militia. In addition to requiring all male civilians to train and serve in the militia of their Parish, the Bermudian Militia included a standing body of trained artillerymen to garrison the numerous fortifications which ringed New London (St. George's). This standing body was created by recruiting volunteers, and by sentencing criminals to serve as punishment. The Bermudian militiamen were called out on numerous occasions of war, and, on one notable occasion, to quell rioting privateers. In 1710, four years after Spanish and French forces seized the Turks Islands from Bermudian salt producers in 1706, they were expelled by Bermudian privateers. Although the Bermudian force operated under a Letter of Marque, its members, as with all military age Bermudian males, were members of the militia. By this time, the 1707 Acts of Union had made Bermudian and other English militiamen British.

Political issues

[edit]Up until the Glorious Revolution in 1688, the Crown and Parliament were in strong disagreement. The English Civil War left a rather unusual military legacy. Both Whigs and Tories distrusted the creation of a large standing army not under civilian control. The former feared that it would be used as an instrument of royal tyranny. The latter had memories of the New Model Army and the anti-monarchical social and political revolution that it brought about. Consequently, both preferred a small standing army under civilian control for defensive deterrence and to prosecute foreign wars, a large navy as the first line of national defence, and a militia composed of their neighbours as additional defence and to preserve domestic order.

Consequently, the English Bill of Rights (1689) declared, amongst other things: "that the raising or keeping a standing army within the kingdom in time of peace, unless it be with consent of Parliament, is against law..." and "that the subjects which are Protestants may have arms for their defense suitable to their conditions and as allowed by law." This implies that they are fitted to serve in the militia, which was intended to serve as a counterweight to the standing army and preserve civil liberties against the use of the army by a tyrannical monarch or government.

The Crown still (in the British constitution) controls the use of the army. This ensures that officers and enlisted men swear an oath to a politically neutral head of state, and not to a politician. While the funding of the standing army subsists on annual financial votes by parliament, the Mutiny Act is also renewed on an annual basis by parliament[citation needed]. If it lapses, the legal basis for enforcing discipline disappears, and soldiers lose their legal indemnity for acts committed under orders[citation needed].

Eighteenth century and the Acts of Union

[edit]In 1707, the Acts of Union united the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland. The Scottish navy was incorporated into the Royal Navy. The Scottish military (as opposed to naval) forces merged with the English, with pre-existing regular Scottish regiments maintaining their identities, though command of the new British Army was from England. The Militia of England and Wales continued to be enacted separately from the Militia of Scotland (see Militia (Great Britain) and, for the period following 1801, Militia (United Kingdom)).

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The two regiments raised in exile were the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards, which later became the Grenadier Guards,[18] and the King's Regiment of Horse Guards, later the Life Guards. The two New Model Army regiments were the Lord General's Regiment of Foot Guards, later the Coldstream Guards, and the King's Regiment of Horse, later the Royal Horse Guards which in turn became the Blues and Royals.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ Beckett pp. 9–10

- ^ Beckett pp. 10–11

- ^ Goring pp. 5–6

- ^ Beckett p. 12

- ^ Goring pp. 6–7

- ^ Goring pp. 3–5

- ^ Goring pp. 14–17

- ^ Ian Heath. "Armies of the Sixteenth Century: The Armies of England, Ireland, the United Provinces, and the Spanish Netherlands 1487–1609." Foundry Books, 1997. Pages 33 and 37.

- ^ Beckett p. 18

- ^ Goring pp. 279–280

- ^ Beckett pp. 20–21

- ^ Beckett pp. 33–34

- ^ Beckett p. 39

- ^ Mallinson pp. 14–17

- ^ Mallinson pp.17–20

- ^ Mallinson p. 23

- ^ Mallinson pp. 29–30. In addition to the four guards regiments, the newly established army comprised some 28 garrisons.

- ^ "History – British Army Website". The British Army. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Mallinson p. 30

- ^ Beckett pp. 46–50

- ^ Mallinson pp. 29–32

- ^ Mallinson pp. 33–35. The army had proved itself useful in the Great Fire of London, in assisting magistrates to put down riots, in the apprehension of highwaymen, and in the building and repair of roads and bridges.

- ^ Mallinson p. 35. King James II added nine new regiments of foot, five of horse and two of dragoons to the army's establishment.

- ^ Mallinson pp. 39–42 & 65

- ^ Mallinson p. 40. The legislation made it illegal to maintain a standing army without the consent of Parliament, which also controlled the army's funding, while giving the Crown prerogative to govern and control the army.

- ^ Beckett pp. 53–56

- ^ Beckett pp. 58–59

Bibliography

[edit]- Beckett, Ian Frederick William (2011). Britain's Part-Time Soldiers: The Amateur Military Tradition: 1558–1945. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9781848843950.

- Goring, J. J. (1955). The Military Obligations of the English People, 1511-1558 (PhD). Queen Mary University of London.

- Hodgkins, Alexander James (2013). Rebellion and Warfare in the Tudor State: Military Organisation, Weaponry, and Field Tactics in Mid-Sixteenth Century England (PhD). The University of Leeds.

- Mallinson, Allan (2009). The Making of the British Army: From the English Civil War to the War on Terror. London: Bantam Press. ISBN 9780593051085.