Copyright Term Extension Act

| |

| Long title | To amend the provisions of title 17, United States Code, with respect to the duration of copyright, and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | CTEA |

| Nicknames | Copyright Term Extension Act, Mickey Mouse Protection Act, Sonny Bono Act |

| Enacted by | the 105th United States Congress |

| Effective | October 27, 1998 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub. L. 105–298 (text) (PDF) |

| Statutes at Large | 112 Stat. 2827 |

| Codification | |

| Acts amended | Copyright Act of 1976 |

| Titles amended | 17 (Copyrights) |

| U.S.C. sections amended | 17 U.S.C. §§ 108, 203(a)(2), 301(c), 302, 303, 304(c)(2) |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

| Eldred v. Ashcroft | |

The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act – also known as the Copyright Term Extension Act, Sonny Bono Act, or (derisively) the Mickey Mouse Protection Act[1] – extended copyright terms in the United States in 1998. It is one of several acts extending the terms of copyright.[2]

Following the Copyright Act of 1976, copyright would last for the life of the author plus 50 years (or the last surviving author), or 75 years from publication or 100 years after creation, whichever is shorter for a work of corporate authorship (works made for hire) and anonymous and pseudonymous works. The 1976 Act also increased the renewal term for works copyrighted before 1978 that had not already entered the public domain from 28 years to 47 years, giving a total term of 75 years.[3]

The 1998 Act extended these terms to life of the author plus 70 years and for works of corporate authorship to 95 years from publication or 120 years after creation, whichever end is earlier.[4] For works published before January 1, 1978, the 1998 act extended the renewal term from 47 years to 67 years, granting a total of 95 years.

This law effectively froze the advancement date of the public domain in the United States for works covered by the older fixed term copyright rules. Under this Act, works made in 1923 or afterwards that were still protected by copyright in 1998 would not enter the public domain until January 1, 2019, or later. Mickey Mouse specifically, having first appeared in 1928 in Steamboat Willie, entered the public domain in 2024[5] with other works following later in accordance with the product's date. Unlike copyright extension legislation in the European Union, the Sonny Bono Act did not revive copyrights that had already expired, and therefore is not retroactive in that sense. The Act did extend the terms of protection set for works that were already copyrighted and were created before it took effect, so it is retroactive in that sense. However, works created before January 1, 1978, but not published or registered for copyright until recently, are addressed in a special section (17 U.S.C. § 303) and may remain protected until the end of 2047. The Act became Pub. L. 105–298 (text) (PDF) on October 27, 1998.

Background

[edit]Prior to the passage of the 1976 Copyright Act, Congress passed nine incremental extensions between 1962 and 1974 for works that were in their renewal term whose copyright began between September 19, 1906, and December 31, 1918.[a] In the Eldred v. Ashcroft decision, the Supreme Court noted that these extensions "were all temporary placeholders subsumed into the systemic changes effected by the 1976 Act."[6] As a result, these works entered the public domain on January 1, following the end of the 75th calendar year after their publication.

Under the international Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works of 1886, the signatory countries are required to provide copyright protection for a minimum term of the life of the author plus fifty years. Additionally, they are permitted to provide for a longer term of protection. The Berne Convention did not come into force for the United States until it was ratified on March 1, 1989, but the U.S. had previously provided for the minimum copyright term the convention required in the Copyright Act of 1976.

After the United States' accession to the Berne convention, a number of copyright owners successfully lobbied the U.S. Congress for another extension of the term of copyright, to provide for the same term of protection that exists in Europe. Since the 1993 Directive on harmonising the term of copyright protection, member states of the European Union implemented protection for a term of the author's life plus seventy years.

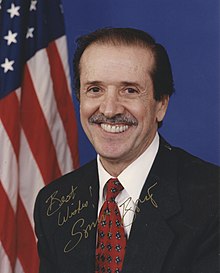

The act was named in memory of the late Congressman Sonny Bono, who died nine months before the act became law: he had previously been one of twelve sponsors of a similar bill.

House members sympathetic to restaurant and bar owners, who were upset over ASCAP and BMI licensing practices, almost derailed the Act. As a result, the bill was amended to include the Fairness in Music Licensing Act, which exempted smaller establishments from needing a public performance license to play music.[7]

Both houses of the United States Congress passed the act as Public Law 105-298 with a voice vote.[8][9] President Bill Clinton signed the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 on October 27, 1998.[10]

As a result of extensions, including the 1976 and 1998 extensions, a small number of renewed works, within a span of 40 years, entered the public domain:

| Works of | Protected by | Copyright expired on |

|---|---|---|

| 1905 | 1909 Copyright Act | By the end of 1961[11] |

| 1907 | 1976 Copyright Act | January 1, 1983 |

| 1921 | 1976 Copyright Act | January 1, 1997[11] |

| 1922 | 1976 Copyright Act | January 1, 1998 |

| 1923 | Copyright Term Extension Act | January 1, 2019 |

From 2019 onwards, works published in a given year enter the public domain at the end of the 95th calendar year after publication. For example, works published in 1928 entered the public domain on January 1, 2024.

Political climate

[edit]Senate Report 104-315

[edit]

The Senate Report[12] gave the official reasons for passing copyright extension laws and was originally written in the context of the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1995.[13]

The purpose of the bill is to ensure adequate copyright protection for American works in foreign nations and the continued economic benefits of a healthy surplus balance of trade in the exploitation of copyrighted works. The bill accomplishes these goals by extending the current U.S. copyright term for an additional 21 years. Such an extension will provide significant trade benefits by substantially harmonizing U.S. copyright law to that of the European Union while ensuring fair compensation for American creators who deserve to benefit fully from the exploitation of their works. Moreover, by stimulating the creation of new works and providing enhanced economic incentives to preserve existing works, such an extension will enhance the long-term volume, vitality and accessibility of the public domain.

The authors of the report believed that extending copyright protection would help the United States by providing more protection for their works in foreign countries and by giving more incentive to digitize and preserve works since there was an exclusive right in them. The report also included minority opinions by Herb Kohl and Hank Brown, who believed that the term extensions were a financial windfall to current owners of copyrighted material at the expense of the public's use of the material.

Support

[edit]

Since 1990, The Walt Disney Company had lobbied for copyright extension.[14][15] The legislation delayed the entry into the public domain of the earliest Mickey Mouse cartoons, leading detractors to the nickname "The Mickey Mouse Protection Act".[1]

In addition to Disney, California congresswoman Mary Bono (Sonny Bono's widow and Congressional successor), and the estate of composer George Gershwin supported the act. Mary Bono, speaking on the floor of the United States House of Representatives, said:

Actually, Sonny wanted the term of copyright protection to last forever. I am informed by staff that such a change would violate the Constitution. ... As you know, there is also [then-MPAA president] Jack Valenti's proposal for term to last forever less one day. Perhaps the Committee may look at that next Congress.[16]

Other parties that lobbied in favor of the Bono Act were Time Warner, Universal, Viacom, ASCAP, the major professional sports leagues (NFL, NBA, NHL, MLB), and the family of slain singer Selena Quintanilla-Pérez.[14][15]

Proponents of the Bono Act argue that it is necessary given that the life expectancy of humans has risen dramatically since Congress passed the original Copyright Act of 1790,[17] that a difference in copyright terms between the United States and Europe would negatively affect the international operations of the entertainment industry,[17][18] and that some works would be created under a longer copyright that would never be created under the existing copyright. They also claim that copyrighted works are an important source of income to the US[18][19] and that media such as VHS, DVD, cable and satellite have increased the value and commercial life of movies and television series.[18]

Proponents contend that Congress has the power to pass whatever copyright term it wants because the language "To promote the progress of science and useful arts" in the United States Constitution is not a substantive limitation on the powers of Congress, leaving the sole restriction that copyrights must only last for "limited times". However, in what respect the granted time must be limited has never been determined, thus arguably even an absurdly long, yet finite, duration would still be a valid limited time according to the letter of the Constitution as long as Congress was ostensibly setting this limit to promote the progress of science and useful arts. This was one of the arguments that prevailed in the Eldred v. Ashcroft case, when the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the CTEA. It is also pointed out by proponents that the extension did not prevent all works from going in the public domain. They note that the 1976 Copyright Act established that unpublished works created before 1978 would still begin entering the public domain January 1, 2003 (Known author: life of the author plus 70 years; anonymous/pseudoanonymous/unknown author/works-for-hire: 120 years from creation), and that the provision remained unaffected by the 1998 extension.[20] They also claim that Congress has actually increased the scope of the public domain since, for the first time, unpublished works will enter the public domain.[20]

Proponents believe that copyright encourages progress in the arts. With an extension of copyright, future artists have to create something original, rather than reuse old work. However, had the act been in place in the 1960s, it is unlikely that Andy Warhol would have been able to sell or even exhibit any of his work, since it all incorporated previously copyrighted material. Proponents contend that it is more important to encourage all creators to make new works instead of just copyright holders.[20]

Proponents say that copyright better preserves intellectual property like movies, music and television shows.[19][20] One example given is the case of the classic film It's a Wonderful Life.[19] Before Republic Pictures and Spelling Entertainment (who owned the motion picture rights to the short story and the music even after the film itself became public domain) began to assert their rights to the film, various local TV stations and cable networks broadcast the film endlessly. As New York Times reporter Bill Carter put it: "the film's currency was being devalued."[21]

Many different versions of the film were made and most if not all were in horrible condition.[22] After underlying rights to the film were enforced, it was given a high quality restoration that was hailed by critics. In addition, proponents note that once a work falls into the public domain there is no guarantee that the work will be more widely available or cheaper. Suggesting that quality copies of public domain works are not widely available, they argue that one reason for a lack of availability may be due to publishers' reluctance to publish a work that is in the public domain for fear that they will not be able to recoup their investment or earn enough profit.[19]

Proponents reject the idea that only works in the public domain can provide artistic inspiration. They note that opponents fail to take into account that copyright applies only to expressions of ideas and not the ideas themselves.[20] Thus artists are free to get ideas from copyrighted works as long as they do not infringe. Borrowing ideas and such are common in film, TV and music even with copyrighted works (see scènes à faire, idea-expression divide and stock character). Works such as parody benefit from fair use.

Proponents also question the idea that extended copyright is "corporate welfare". They state that many opponents also have a stake in the case, claiming that those arguing against copyright term extension are mostly businesses that depend on distributing films and videos that have lost their copyright.[19]

One argument against the CTEA is focused on the First Amendment. In Harper & Row v. Nation Enterprises, however, the court explained how a copyright "respects and adequately safeguards the freedom of speech protected by the First Amendment."[23] In following this approach, courts have held that copyrights are "categorically immune from challenges under the First Amendment."[23]

Opposition

[edit]Critics of the CTEA argue that it was never the original intention for copyright protection to be extended in the United States. Attorney Jenny L. Dixon mentions that "the United States has always viewed copyright primarily as a vehicle for achieving social benefit based on the belief that encouragement of individual effort by personal gain is the best way to advance the public welfare;"[24] however, "the U.S. does not consider copyright as a 'natural right.'"[24] Dixon continues that with increased extensions on copyright protections, authors receive the benefits, while the public have more difficulty accessing these works, weakening public domain.[24] One such extension Dixon mentions is the protection of a copyrighted work for the author's life followed by two generations, which opponents argue that there is no legislation nor intention for this copyright protection.[24] "These constitutionally-grounded arguments 'for limitations on proprietary rights' are being rejected time and time again."[24]

Dennis S. Karjala, a law professor, led an effort to try to prevent the CTEA from being passed. He testified before the Committees on the Judiciary arguing "that extending the term of copyright protection would impose substantial costs on the United States general public without supplying any public benefit. The extension bills represent a fundamental departure from the United States philosophy that intellectual property legislation serve a public purpose."[25]

An editorial in The New York Times argued against the copyright extension on February 21, 1998. The article stated "When Senator Hatch laments that George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue will soon 'fall into the public domain,' he makes the public domain sound like a dark abyss where songs go, never to be heard again. In fact, when a work enters the public domain it means the public can afford to use it freely, to give it new currency."[26]

Opponents of the Bono Act consider the legislation to be corporate welfare and have tried (but failed) to have it declared unconstitutional in the process Eldred v. Ashcroft, claiming that such an act is not "necessary and proper" to accomplishing the Constitution's stated purpose of "promot[ing] the progress of science and useful arts".[27][28] They argue that most works bring most of the profits during the first few years and are pushed off the market by the publishers thereafter. Thus there is little economic incentive in extending the terms of copyrights except for the few owners of franchises that are wildly successful, such as Disney. They also point out that the Tenth Amendment can be construed as placing limits on the powers that Congress can gain from a treaty. More directly, they see two successive terms of approximately 20 years each (the Copyright Act of 1976 and the Bono Act) as the beginning of a "slippery slope" toward a perpetual copyright term that nullifies the intended effect and violates the spirit of the "for limited times" language of the United States Constitution, Article I, section 8, clause 8.[29]

Some opponents have questioned the proponents' life expectancy argument, making the comparison between the growth of copyright terms and the term of patents in relation to the growth of life expectancies. Life expectancies have risen from about 35 years in 1800[30] to 77.6 years in 2002.[31] While copyright terms have increased threefold, from only 28 years total (under the Copyright Act of 1790), life expectancies have roughly doubled. Moreover, life expectancy statistics are skewed due to historically high infant mortality rates. Correcting for infant mortality, life expectancy has only increased by fifteen years between 1850 and 2000.[32] In addition, copyright terms have increased significantly since the 1790 act, but patent terms have not been extended in parallel, with 20-year terms of protection remaining the (presumably under the laws) adequate compensation for innovation in a technical field.[33] Seventeen prominent economists and libertarians, including Nobel Prize laureates (George Akerlof, Kenneth Arrow, James Buchanan, Ronald Coase, and Milton Friedman), submitted an amicus brief opposing the bill when it was challenged in court. They argued that the discounted present value of the extension was only a 1% increase for newly created works, while the increase in transaction costs created by extending the terms of old works would be very large and without any marginal benefit.[34] According to Lawrence Lessig, when asked to sign the brief, Friedman had originally insisted that it include "the word 'no-brainer' in it somewhere," but still agreed to sign it even though his condition was not met.[35]

Another argument against the CTEA is focused on the First Amendment "because of the prospective and retrospective application of the CTEA."[23] The plaintiffs in Eldred v. Reno believed that "the CTEA failed to sustain the intermediate level of scrutiny test afforded by the First Amendment because the government did not have an 'important' interest to justify withholding speech."[23]

Opponents also argue that the Act encourages "offshore production," in which derivative works could be created outside the United States in areas where copyright would have expired, but US law would prohibit these works from being shown to US residents. For example, a cartoon of Mickey Mouse playing with a computer could be legally created in Russia, but the cartoon would be refused admission for importation by US Customs due to infringing US copyrights.[36]

Opponents identify another possible harm from copyright extension: loss of productive value of private collections of copyrighted works. A person who collected copyrighted works that would soon "go out of copyright", intending to re-release them on copyright expiration, lost the use of their capital expenditures for an additional 20 years when the Bono Act passed. This is part of the underlying argument in Eldred v. Ashcroft.[37] The Bono Act is thus perceived to add an instability to commerce and investment, areas which have a better legal theoretical basis than intellectual property, whose theory is of quite recent development and is often criticized as being a corporate chimera. Conceivably, if one had made such an investment and then produced a derivative work (or perhaps even re-released the work in ipse), he could counter a suit made by the copyright holder by declaring that Congress had unconstitutionally made, ex post facto, a restriction on the previously unrestricted.

Howard Besser questioned the proponents' argument that "new works would not be created", which implies that the goal of copyright is to make the creation of new works possible. However, the Framers of the United States Constitution evidently thought that unnecessary, instead restricting the goal of copyright to merely "promot[ing] the progress of science and useful arts". In fact, some works created under time-limited copyright would not be created under perpetual copyright because the creator of a distantly derivative work does not have the money and resources to find the owner of copyright in the original work and purchase a license, or the individual or privately held owner of copyright in the original work might refuse to license a use at any price (though a refusal to license may trigger a fair use safety valve). Thus they argue that a rich, continually replenished, public domain is necessary for continued artistic creation.[38]

March 25, 1998, House debate

[edit]The House debated the Copyright Term Extension Act (House Resolution 390) on March 25, 1998.[39] The term extension was almost completely supported, with only the mild criticism by Jim Sensenbrenner (Wisconsin) of "H.R. 2589 provides a very generous windfall to the entertainment industry by extending the term of copyright for an additional 20 years."[40] He suggested that it could be balanced by adding provisions from the Fairness in Music Licensing Act (H.R. 789). Lloyd Doggett (Texas) called the 'Fairness in Music Licensing Act' the 'Music Theft Act' and claimed that it was a mechanism to "steal the intellectual property of thousands of small businesspeople who are song writers in this land."[41] The majority of subsequent debate was over Sensenbrenner's House Amendment 532[42] to the CTEA. This amendment was over details of allowing music from radio and television broadcasts in small businesses to be played without licensing fees. An amendment to Sensenbrenner's amendment was proposed by Bill McCollum.[43] The key differences between Sensenbrenner's proposal and McCollum's amendment were 1) local arbitration versus court lawsuits in rate disagreements, 2) all retail businesses versus only restaurants and bars, 3) 3500 square feet of general public area versus 3,500 square feet (330 m2) of gross area, 4) which music licensing societies it applied to (all versus ASCAP and BMI), and 5) freedom from vicarious liability for landlords and others leasing space versus no such provision.[44] After debate (and the first verse of American Pie[45]) the McCollum Amendment was rejected by a vote of 259 to 150[46] and the Sensenbrenner amendment was passed by 297 to 112.[47] The Copyright Term Extension Act H.R. 2589 was passed.[48]

The term extension was supported for two key reasons. First, "copyright industries give us [the United States] one of our most significant trade surpluses." Second, the recently enacted legislation in the European Union had extended copyright there for 20 years, and so EU works would be protected for 20 years longer than US works if the US did not enact similar term extensions. Howard Coble also stated that it was good for consumers since "When works are protected by copyright, they attract investors who can exploit the work for profit."[49] The term extension portion was supported by Songwriters Guild of America, National Academy of Songwriters, the Motion Picture Association of America, the Intellectual Property Law Section of the American Bar Association, the Recording Industry Association of America, National Music Publishers Association, the Information Technology Association of America and others.[50]

Challenges

[edit]Legal

[edit]Publishers and librarians, among others, brought a lawsuit, Eldred v. Ashcroft, to obtain an injunction on enforcement of the act. Oral arguments were heard by the U.S. Supreme Court on October 9, 2002. On January 15, 2003, the court held the CTEA constitutional by a 7–2 decision.[51]

In 2003, the plaintiffs in the Eldred case began to shift their effort toward the U.S. Congress in support of a bill called the Public Domain Enhancement Act that would make the provisions of the Bono Act apply only to copyrights that had been registered with the Library of Congress.

In May 2022, Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) introduced a bill that would roll back the copyright term for new works to match to the 1909 Copyright Act, but also applies retroactively to works by a group of large companies specifically designed to target Disney. Sarah Jeong of The Verge criticized the bill for obviously violating international agreements and the Fifth Amendment protections against eminent domain, as an attempt to punish Disney for opposing Florida House Bill 1557, and because it is unlikely to pass in a Congress where Democrats control both houses.[52][53]

Empirical testing

[edit]In 2012, law professors Christopher Buccafusco and Paul J. Heald performed tests of three key justifications of copyright extension, namely: that public domain works will be underutilized and less available, will be oversaturated by poor quality copies, and poor quality derivative works will harm the reputation of the original works. They compared works from the two decades surrounding 1923 made available as audiobooks. They found that copyrighted works were significantly less likely to be available than public domain ones, found no evidence of overexploitation driving down the price of works, and that the quality of the audiobook recordings did not significantly affect the price people were willing to pay for the books in print.[54] Heald's later experiment analyzing a random sample of newly posted works on Amazon.com revealed that public domain works from 1880 were posted at double the rate of copyrighted works from 1980.[55]

See also

[edit]- Anti-copyright

- Copyright

- Copyleft

- Digital Millennium Copyright Act

- Ex post facto law

- Free Culture (2004 book)

- Intellectual property

- List of countries' copyright length

- Motion Picture Association of America

- Public domain

- Rent seeking

- Recording Industry Association of America

- Software copyright

- United States copyright law

- European Union 95 year recording copyright extension proposal

Notes

[edit]- ^ See Pub. L. 87-668, 76 Stat. 555; Pub. L. 89-142, 79 Stat. 581; Pub. L. 90-141, 81 Stat. 464; Pub. L. 90-416, 82 Stat. 397; Pub. L. 91-147, 83 Stat. 360; Pub. L. 91-555, 84 Stat. 1441; Pub. L. 92-170, 85 Stat. 490; Pub. L. 92-566, 86 Stat. 1181; Pub. L. 93-573, Title I, 88 Stat. 1873.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Lawrence Lessig, Copyright's First Amendment, 48 UCLA L. Rev. 1057, 1065 (2001)

- ^ Duration of Copyright – United States Copyright Office

- ^ (www.copyright.gov), U.S. Copyright Office. "U.S. Copyright Office – Certain Unpublished, Unregistered Works Enter Public Domain". www.copyright.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- ^ U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 1: Copyright Basics, pp. 5–6

- ^ "Mickey's Headed to the Public Domain! But Will He Go Quietly? – Office of Copyright". Office of Copyright. October 17, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- ^ "ELDRED ET AL. v. ASHCROFT, ATTORNEY GENERAL" (PDF).

- ^ William Patry, 1 Patry on Copyright § 1:97 (Thomson Reuters/West 2009)

- ^ "Thomas: Status of H.R. 2589". Thomas.loc.gov. Archived from the original on July 5, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "Thomas: Status of S. 505". Thomas.loc.gov. Archived from the original on July 4, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Copyright Office: Annual Report 2002: Litigation". Copyright.gov. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ a b United States Copyright Office (February 2023). "Duration of Copyright" (PDF). Copyright.gov. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ "Senate Report 104-315". Thomas.loc.gov. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "S.483 – Copyright Term Extension Act of 1996". Congress.gov. July 10, 1996. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Greenhouse, Linda (February 20, 2002). "Justices to Review Copyright Extension". The New York Times. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

The 1998 extension was a result of intense lobbying by a group of powerful corporate copyright holders, most visibly Disney, which faced the imminent expiration of copyrights on depictions of its most famous cartoon characters.

- ^ a b Ota, Alan K. (August 10, 1998). "Disney In Washington: The Mouse That Roars". CNN. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ "H9952". Congressional Record. Government Printing Office. October 7, 1998. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ a b "Senator Orrin Hatch's Introduction of The Copyright Term Extension Act of 1997". March 20, 1997. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Senator Dianne Feinstein's Statement before Congress". March 20, 1997. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Excerpts of Bruce A. Lehman's statement before Congress". September 20, 1995. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Scott M. Martin (September 24, 2002). "The Mythology of the Public Domain: Exploring the Myths Behind Attacks on the Duration of Copyright Protection". Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review. 36 (1). Loyola Law Review: 280. ISSN 1533-5860. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ Carter, Bill (December 19, 1994). "The Media Business; Television". The New York Times. pp. D10. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ "See Two Days of Christmas Classics", Toronto Star, December 24, 1999, At E1.

- ^ a b c d Grzelak, Victoria A. (2002). "Mickey Mouse & Sonny Bono Go to Court: The Copyright Term Extension Act and its Effect on Current and Future Rights". Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Dixon, Jenny L. "The Copyright Term Extension Act: Is Life Plus Seventy Too Much". HeinOnline. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ^ Karjala, Dennis. "Opposing Copyright Extension, Legislative Materials (105th Congress), Statement of Copyright and Intellectual Property Law Professors in Opposition to H.R. 604, H.R. 2589, and S.505". Archived from the original on November 16, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ "Keeping Copyright in Balance". The New York Times. February 21, 1998.

- ^ "Brief of Intellectual Property Law Professors as Amici Curie Supporting Petitioners" (PDF). Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ Steelman, Aaron (2008). "Intellectual Property". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). Nozick, Robert (1938–2002). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Cato Institute. pp. 249–250. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n220. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- ^ "Cornell University Law School – United States Constitution". Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "Life Expectancies in 1800s". Answers.com. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "Life Expectancies in 2002". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "Life Expectancy by Age, 1850–2011". InfoPlease. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ "United States Patent and Trademark Office – General Information". Uspto.gov. Archived from the original on February 1, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "Brief of George A. Akerlof, Kenneth J. Arrow, Timothy F. Bresnahan, James M. Buchanan, Ronald H. Coase, Linda R. Cohen, Milton Friedman, Jerry R. Green, Robert W. Hahn, Thomas W. Hazlett, C. Scott Hemphill, Robert E. Litan, Roger G. Noll, Richard Schmalensee, Steven Shavell, Hal R. Varian, and Richard J. Zeckhauser as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ Lawrence Lessig. ""only if the word 'no-brainer' appears in it somewhere": RIP Milton Friedman". Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

No doubt the highpoint of the Eldred v. Ashcroft case was when I learned Friedman would sign our "Economists' Brief": As it was reported to me, when asked, he responded: "Only if the world [sic] 'no brainer' appears in it somewhere." A reasonable man, he signed even though we couldn't fit that word in.

- ^ Macavinta, Courtney. "CNET – Copyright extension law". News.cnet.com. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "Salon.com Technology | Mickey Mouse vs. The People". Archive.salon.com. February 21, 2002. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ Howard Besser, The Erosion of Public Protection: Attacks on the concept of Fair Use Archived September 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Paper delivered at the Town Meeting on Copyright & Fair Use, College Art Association, Toronto, February 1998. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ^ Congressional Record, Volume 144, 1998, H1456–H1483, March 25, 1998

- ^ Congressional Record, Volume 144, 1998, H1459

- ^ Congressional Record, Volume 144, 1998, H1457

- ^ http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.uscongress/legislation.105hamdt532 "Handle Problem Report (Library of Congress)". Hdl.loc.gov. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.uscongress/legislation.105hamdt533 "Handle Problem Report (Library of Congress)". Hdl.loc.gov. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ Congressional Record, Volume 144, 1998, H1470–H1471

- ^ Congressional Record, Volume 144, 1998, H1471

- ^ Congressional Record, Volume 144, 1998, H1482

- ^ Congressional Record, Volume 144, 1998, H1482–H1483

- ^ Congressional Record, Volume 144, 1998, H1483

- ^ Congressional Record, Volume 144, 1998, Coble, North Carolina, H1458

- ^ Congressional Record, Volume 144, 1998, H1463

- ^ Timothy B. Lee (October 25, 2013). "15 years ago, Congress kept Mickey Mouse out of the public domain. Will they do it again?". The Washington Post.

- ^ Lang, Jamie (May 11, 2022). "U.S. Congressman Proposes Bill To Strip Disney Of Long-Held Copyrights". Cartoon Brew. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ Jeong, Sarah (May 10, 2022). "Josh Hawley wants to punish Disney by taking copyright law back to 1909 and that sucks". The Verge.

- ^ Buccafusco, Christopher; Heald, Paul J. (August 15, 2012). "Do Bad Things Happen When Works Enter the Public Domain?: Empirical Tests of Copyright Term Extension". Berkeley Technology Law Journal. SSRN 2130008.

- ^ Heald, Paul J. (July 5, 2013). "How Copyright Keeps Works Disappeared". University of Illinois, Public Law & Legal Theory, Research Paper Series. SSRN 2290181.

External links

[edit]![]() Works related to Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act at Wikisource

Works related to Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act at Wikisource

Summary of copyright protection terms

[edit]Documentation from the United States government

[edit]Views of proponents

[edit]- Copyright Extension.com

- Mythology of the public domain: Exploring the myths behind attacks on the duration of copyright by Scott Martin