Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt

Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Michiel Janszoon van Mierevelt (c. 1610–25) by Willem Jacobsz. Delff | |

| Born | 1 May 1566 |

| Died | 27 June 1641 (aged 75) Delft, Dutch Republic |

| Signature | |

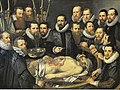

Michiel Janszoon (abbr. Jansz.)[1] van Mierevelt (Dutch pronunciation: [miˈxil ˈjɑnsoːɱ vɑ ˈmiːrəvɛlt, - ˈjɑns fɑ -];[a] also spelled Miereveld or Miereveldt; 1 May 1566 – 27 June 1641) was a Dutch painter and draftsman of the Dutch Golden Age.[2]

Biography

[edit]Van Mierevelt was born and died in Delft, as a son of a goldsmith, who apprenticed him to the copperplate engraver Hieronymus Wierix. He subsequently became a pupil of Willem Willemz and Augusteyn of Delft, until Anthonie van Montfoort (Houbraken calls him Antony Blokland[3]), who had seen and admired two of Mierevelt's early engravings, Christ and the Samaritan and Judith and Holofernes, invited him to enter his school at Utrecht.[4]

He registered as a member of the Guild of St. Luke in The Hague in 1625.[5] Devoting himself first to still lifes, he eventually took up portraiture, in which he achieved such success that the many commissions entrusted to him necessitated the employment of numerous assistants, by whom hundreds of portraits were turned out in factory fashion. Today over 500 paintings are or have been attributed to him.[5] The works that can with certainty be ascribed to his own brush are remarkable for their sincerity, severe drawing and harmonious color, but comparatively few of the two thousand or more portraits that bear his name are wholly his own handiwork. So great was his reputation that he was patronized by royalty in many countries and acquired great wealth. The king of Sweden and the count palatine of Neuburg presented him with golden chains; Albert VII, Archduke of Austria, at whose court he lived in Delft, gave him a pension; and Charles I vainly endeavoured to induce him to visit the English court.[6][7]

Though Mierevelt is chiefly known as a portrait painter, he also executed some mythological pieces of minor importance. Many of his portraits have been reproduced in line by the leading Dutch engravers of his time. He died at Delft.[8]

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has the richest collection of Mierevelt's works, chief of them being the portraits of William, Philip William, Maurice, and Frederick Henry of Orange, and of the count palatine Frederick V. At the Mauritshuis in The Hague are the portraits of four princes of the house of Orange, of Frederick V as king of Bohemia, and of Louise de Coligny as a widow. Other portraits by him are at nearly all the leading continental galleries, notably at Brunswick (3), Gotha (2), Schwerin (3), Munich (2), Paris (Louvre, 3), Dresden (4), Berlin (2), and Darmstadt (3). The town hall of Delft also has numerous examples of his work.[8]

Legacy

[edit]Many of his pupils and assistants rose to fame. The most gifted of them were Paulus Moreelse, Jan Antonisz. van Ravesteyn,[8] Daniel Mijtens, Anthonie Palamedesz., Johan van Nes, and Hendrick Cornelisz. van Vliet.[5] His sons Pieter (1596–1623) and Jan (died 1633), and his son-in-law Jacob Delff,[citation needed] probably painted many of the pictures which go under his name. His portrait was painted by Anthony van Dyck and engraved by Jacob Delff.[8]

- Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt's works

-

Philip William

-

Engraved after Michiel van Miereveld, Ambrogio Spinola, 1623, engraving, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

-

Michiel Jansz van Mierevelt, Portrait of a woman, Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon

-

Portrait of a Woman

-

Portrait of a Young Woman

-

Double Portrait of a Husband and Wife with Tulip, Bulb, and Shells oil on panel painting by Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt, 1609

Notes

[edit]- ^ In isolation, Janszoon and van are pronounced [ˈjɑnsoːn] and [vɑn], respectively.

References

[edit]- ^ "Michiel Janszoon van Mierevelt – Dutch painter". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ Michiel van Mierevelt, Netherlands Institute for Art History. Retrieved on 17 April 2015.

- ^ Michiel Mierevelt biography in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1718) by Arnold Houbraken, courtesy of the Digital library for Dutch literature

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 424.

- ^ a b c RKD entry on Mierevelt

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 424–425.

- ^ Gilman, Peck & Colby 1905, p. 464.

- ^ a b c d Chisholm 1911, p. 425.

Sources

[edit]- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia. Vol. 13 (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. p. 469.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mierevelt, Michiel Jansz van". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 424–425.

External links

[edit]- 73 artworks by or after Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt at the Art UK site

- Works and literature on Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt

- Vermeer and The Delft School, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which contains material on Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt