Pop (U2 album)

| Pop | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 3 March 1997 | |||

| Recorded | 1995–1996 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 60:09 | |||

| Label | Island | |||

| Producer | ||||

| U2 chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Pop | ||||

| ||||

Pop is the ninth studio album by Irish rock band U2. It was produced by Flood, Howie B, and Steve Osborne, and was released on 3 March 1997 on Island Records. The album was a continuation of the band's 1990s musical reinvention, as they incorporated alternative rock, techno, dance, and electronica influences into their sound. Pop employed a variety of production techniques that were relatively new to U2, including sampling, loops, programmed drum machines, and sequencing.

Recording sessions began in 1995 with various record producers, including Nellee Hooper, Flood, Howie B, and Osborne, who were introducing the band to various electronica influences. At the time, drummer Larry Mullen Jr. was inactive due to a back injury, prompting the other band members to take different approaches to songwriting. Upon Mullen's return, the band began re-working much of their material but ultimately struggled to complete songs. After the band allowed manager Paul McGuinness to book their upcoming 1997 PopMart Tour before the record was completed, they felt rushed into delivering it. Even after delaying the album's release date from the 1996 Christmas and holiday season to March 1997, U2 ran out of time in the studio, working up to the last minute to complete songs.

In February 1997, U2 released Pop's techno-heavy lead single, "Discothèque", one of six singles from the album. The record initially received favourable reviews from critics and reached number one in 35 countries, including the United Kingdom and the United States. However, the album's lifetime sales are among the lowest in U2's catalogue, and it received only a single platinum certification by the Recording Industry Association of America.[2] Retrospectively, the album is viewed by some of the music press and public as a disappointment. The finished product was not to U2's liking, and they subsequently re-recorded and remixed many of the songs for single and compilation album releases. The time required to complete Pop cut into the band's rehearsal time for the tour, which affected the quality of initial shows.

Background and writing

[edit]In the first half of the 1990s, U2 underwent a dramatic shift in musical style. The band had experimented with alternative rock and electronic music and the use of samples on their 1991 album, Achtung Baby, and, to a greater extent, on 1993's Zooropa. In 1995, the group's side-projects provided them an opportunity to delve even deeper into these genres. Bassist Adam Clayton and drummer Larry Mullen, Jr. recorded "Theme from Mission: Impossible" in an electronica style. The recording was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Pop Instrumental Performance in 1997 and was an international top-ten hit. In 1995, U2 and Brian Eno recorded an experimental album, Original Soundtracks 1, under the moniker "Passengers". The project included Howie B, Akiko Kobayashi and Luciano Pavarotti, among others.

Bono and the Edge had written a few songs before recording started for Pop in earnest. "If You Wear That Velvet Dress", "Wake Up Dead Man",[3] "Last Night on Earth" and "If God Will Send His Angels" were originally conceived during the Zooropa sessions.[4] "Mofo" and "Staring at the Sun" were also partly written already.[5]

Recording and production

[edit]For the new record, U2 wanted to continue their sonic experimentation from Achtung Baby and Zooropa. To do so, they employed multiple producers to have additional people with whom to share their ideas.[5] Flood was principal producer, having previously worked with the group as engineer for The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby, and co-producer of Zooropa. Mark "Spike" Stent and Howie B were principal engineers. Flood described his job on Pop as a "creative coordinator", saying, "There were some tracks where I didn't necessarily have a major involvement... but ultimately the buck stopped with me. I had the role of the creative supervisor who judged what worked and didn't work."[5] Howie B had previously provided mixing, treatments, and scratching for Original Soundtracks 1. On Pop, he was initially given the role of "DJ and Vibes" before assuming responsibilities as co-producer, engineer, and mixer. One of his main tasks was to introduce the band to sounds and influences within electronica. The band and Howie B regularly went out to dance clubs to experience club music and culture.[5] The overall goal for the record was to create a new sound for the band that was still recognisable as U2.[5]

U2 began work on Pop in mid-1995, collaborating with Nellee Hooper in London, France, and Ireland.[5] In September, the band moved the recording sessions to Hanover Quay in Dublin to a studio the band had just converted from a warehouse.[6] The studio was designed to be more of a rehearsal space more than an actual studio.[6] Flood, Howie B, Steve Osborne, and Marius de Vries joined Hooper and the band there, each of them incorporating their influences and experiences in electronic dance music.[5] Flood described Howie's influence thus: "Howie would be playing all kinds of records to inspire the band and for them to improvise to. That could be anything from a jazz trumpet solo to a super groove funk thing, with no holds barred. We also programmed drum loops, or took things from sample CDs; anything to get the ball rolling. U2 arrive in the studio with very little finished material." These sessions lasted until December 1995, and around 30–40 pieces of music emerged during this period.[5]

Mullen, who had mostly been absent from the sessions to start a family and nurse a worsening back injury, had major surgery on his back in November 1995.[7] Mullen was unable to drum properly during this period, forcing U2 to abandon their usual methods of songwriting as a group but also allowing them to pursue different musical influences.[5] Mullen admits that he was upset that the band entered the studio without him, cognizant that key decisions would be made in the early months of recording.[7] Eno attempted to convince the other band members to wait for Mullen, but as the Edge explains, "The thinking was that we were going to further experiment with the notion of what a band was all about and find new ways to write songs, accepting the influence, and aesthetics of dance music... we thought, 'Let's just start with Howie mixing drum beats and see where that gets us.'"[7] Mullen was back in the studio three weeks after his surgery, but his back prevented him from fully dedicating himself to recording. As he described, "I needed a little more time to recover. But we were struggling with some of the material and for the project to move ahead, I had to put a lot of time in."[8] Sessions ceased temporarily in January 1996 to allow Mullen to rehabilitate.[5]

"It was quite hard for the band to shift from having played to loops of other people to playing to loops of themselves. We felt it was essential to do that, though, because you can get very lazy with samples. They're an easy way to get the ball rolling, but you're always in danger of sounding like some basic samples with the band on top. You're in danger of being dictated to by what's there, rather than saying: 'this is just our springboard'."

Following Mullen's return and the sessions' resumption in February 1996, the production team of Flood, Howie B, and Hooper spent three months attempting to re-work much of the band's material to better incorporate loops and samples with their musical ideas from 1995. This period was a difficult one;[5] Mullen, in particular, had to record drum parts to replace loops that Howie B had sampled without permission.[8] Flood said, "We took what we had and got the band to play to it and work it into their own idiom, while incorporating a dance ethic... The groove-orientated way of making music can be a trap when there's no song; you end up just plowing along on one riff. So you have to try to get the groove and the song, and do it so that it sounds like the band, and do it so that it sounds like something new."

Despite the initial difficulties with sampling, the band and production team eventually became comfortable with it, even sampling Mullen's drumming, the Edge's guitar riffs, Clayton's bass lines, and Bono's vocalisations.[5] Howie B sampled almost anything he could in order to find interesting sounds. He created sequenced patterns of the Edge's guitar playing, which the guitarist, having never done it before, found very interesting. Howie B explained, "Sometimes I would sample, say, a guitar, but it wouldn't come back sounding like a guitar; it might sound more like a pneumatic drill, because I would take the raw sound and filter it, really destroy the guitar sound, and rebuild it into something completely different."[5] Although sequencing was used, mostly on keyboards, guitar loops, and some percussion, it was used sparingly out of fear of becoming overreliant on it.[5]

Nellee Hooper left the sessions in May 1996 due to his commitments to the Romeo + Juliet film score. The recording sessions changed radically in the last few months, which is why Hooper was not credited on the album.[5]

By forcing the band members out of their individual comfort zones, the producers were able to change U2's approach to songwriting and playing their instruments.[5] Mullen, in particular, was forced to do this, as he used samples of other records, sample CDs, or programmed drums while recuperating. Although he eventually reverted to recording his own samples, the experience of using others' changed his approach to recording rhythms.[5][9]

During the recording sessions, U2 allowed manager Paul McGuinness to book their upcoming PopMart Tour before they had completed the album, putting the tour's start date at April 1997.[10] The album was originally planned to be completed and released in time for the 1996 Christmas and holiday season, but the band found themselves struggling to complete songs,[10] necessitating a delay in the album's release date until March 1997. Even with the extended timeframe to complete the album, recording continued up to the last minute.[10] Bono devised and recorded the chorus to "Last Night on Earth" on, coincidentally, the last night of the album's recording and mixing.[10] When Howie B and the Edge took the album to New York City to be mastered, changes and additions to the songs were still being made. During the process, Howie B was adding effects to "Discothèque", while the Edge was recording backing vocals for "The Playboy Mansion". Of the last minute changes, the Edge said, "It's a sign of absolute madness."[10] Flood says, "We had three different mixes of 'Mofo', and during mastering in November '96 in New York, I edited a final version of 'Mofo' from these three mixes. So even during mastering, we were trying to push the song to another level. It was a long process of experimentation; the album didn't actually come together until the last few months."[5]

Ultimately, U2 felt that Pop had not been completed to their satisfaction. The Edge described the finished album as "a compromise project by the end. It was a crazy period trying to mix everything and finish recording and having production meetings about the upcoming tour... If you can't mix something, it generally means there's something wrong with it..."[10] Mullen said, "If we had two or three more months to work, we would have had a very different record. I would like someday to rework those songs and give them the attention and time that they deserve."[10] McGuinness disagrees that the band did not have enough time, saying, "It got an awful lot of time, actually. I think it suffered from too many cooks [in the kitchen]. There were so many people with a hand in that record it wasn't surprising to me that it didn't come through as clearly as it might have done... It was also the first time I started to think that technology was getting out of control."[10] The band ended up re-working and re-recording many songs for the album's singles, as well as for the band's 2002 compilation The Best of 1990-2000.

Composition

[edit]

"I thought 'pop' was a term of abuse, it seemed sort of insulting and lightweight. I didn't realise how cool it was. Because some of the best music does have a lightweight quality, it has a kind of oxygen in it, which is not to say it's emotionally shallow. We've had to get the brightly coloured wrapping paper right, because what's underneath is not so sweet."

—Bono describing the difference between the "surface" of the songs to "what lies beneath".[11]

Pop features tape loops, programming, sequencing, sampling, and heavy, funky dance rhythms.[12] The Edge said in U2's fan magazine Propaganda that, "It's very difficult to pin this record down. It's not got any identity because it's got so many." Bono has said that the album "begins at a party and ends at a funeral", referring to the upbeat and party-like first half of the album and sombre and dark mood of the second half. According to Flood, the production team worked to achieve a "sense of space" on the record's sound by layering all the elements of the arrangements and giving them places in the frequency spectrum where they did not interfere with each other through the continual experimenting and re-working of song arrangements.[5]

Clayton's bass guitar was heavily processed, to the point that it sounded like a keyboard bass (an instrument utilized on "Mofo").[5] The Edge wanted to steer away from the image he had since the 1980s as having an echo-heavy guitar sound. As a result, he was enthusiastic about experimenting with his guitar's sound, hence the distorted guitar sounds on the album, achieved with a variety of effects pedals, synthesisers and knob twiddling. Bono was very determined to avoid the vocal style present on previous (especially 1980s) albums, characterized by pathos, rich timbre, a sometimes theatrical quality and his use of falsetto singing: instead he opted for a rougher, more nervous and less timbre-laden style. The production team made his voice sound more intimate, as up-front and raw as possible. As Flood explained, "You get his emotional involvement with the songs through the lyrics and the way he reacts to the music—without him having to go to 11 all the time... We only used extreme effects on his voice during the recording, for him to get himself into a different place, and then, gradually, we pulled most effects out."[5]

"Edge has been given this tag of having a certain type of sound, which isn't really fair, because on the last two or three albums he's already moved away from it; but people still perceive him as the man with the echoey guitar sound. So he was up for trying out all sorts of ideas, from using cheap pedals and getting the most ridiculous sounds, like in 'Discothèque', to very straight, naked guitar sounds, like in 'The Playboy Mansion'."

—Flood, describing Edge's guitar work on Pop[5]

"Discothèque", the lead single, begins with a distorted acoustic guitar that is passed through a loud amplifier and a filter pedal, along with being processed through an ARP 2600 synthesizer. The song's riff and techno dance rhythm are then introduced. The break in the song's rhythm section features guitar sounds utilizing a "Big Cheese", an effects pedal made by Lovetone.[5] Writer John D. Luerssen noted that the song is "often cited as U2's first experiment with electronica," calling it "a continuation of the experimentation the band had done on Zooropa."[13]

"Do You Feel Loved", which was considered for a single release,[5] runs at a slower pace and features electronic elements. Bono said of the song: "It's quite a question, but there's no question mark on it," as the band took the question mark off the title of the song for fearing it would be perceived as "too heavy."[13]

"Mofo" is the most overtly techno track on the record. Bono's lyrics lament the loss of his mother. There are little guitar and vocal samples that the band played and the production team sampled. They selected the bits that they liked, and then Edge played them back in a keyboard. Pop's producer Flood also put some of guitar work through the ARP 2600 on this track.[5]

"If God Will Send His Angels" is a ballad with Bono pleading for God's help. Like the other singles, the single version is different from the album version. Written on acoustic guitar, D. Leurssen described it as a "techno-tinged ballad".[14] Bono originally thought the song was too soft and asked to "fuck it up," saying "I thought, this is, like, pure. Now drop acid onto that."[14]

"Staring at the Sun" features acoustic guitars and a distorted guitar riff from Edge, and a simple rhythm section from Mullen. The backing track was played to the ARP 2600 running in free time, playing an odd drum-like sequence.

"Last Night on Earth" is anthemic with fuzzy, layered guitars, a funk-inspired bass line, and vocal harmonies during the song's bridge.

"Gone" features a "siren" effect from Edge's guitar, complex krautrock style drums from Mullen and a funk-inspired bass line. This track was also considered for release as a single.[5] Flood applied VCS3 spring reverb and ring modulation in a few places, and used it a lot on the basic rhythm track of this song.

"Miami" has a trip rock style. It begins with a drum loop, with Mullen's hi-hats playing backwards through a very extreme equalization filter. Howie B explained, "The main groove is actually just Larry's hi-hat, but it sounds like a mad engine running or something really crazy – about as far away from a hi-hat as you can imagine... the task in 'Miami' was to make it unlike anything else on the album, and also unlike anything else you'd ever have heard before." Edge also comes in with a frenetic guitar riff and Bono's affected vocal style singing about Miami in metaphors and descriptions of loud, brash Americana. D. Leurssen described it as a "sonic travelogue," while the Edge termed it "creative tourism."[15] In 2005, Q magazine included the song "Miami" in a list of "Ten Terrible Records by Great Artists". However, Andrew Unterberger of Stylus Magazine acknowledged the inclusion of the song in Q's list and said "I’m pretty sure they gave this album some super-glowing review when it was first released, so clearly they’re not to be trusted in the first."[16]

"The Playboy Mansion" starts out with mellow, wah-wah guitar playing from Edge. Along with Mullen's drumming, there are breakbeats and hip-hop beats on the rhythm track, which were recorded as loops by Mullen. Howie described the loops thus; "Larry went off into a side room and made some sample loops of him playing his kit, and gave the loops to me and Flood. It was the same with the guitars; there's a guitar riff which comes in the verse and chorus, which is a sample of Edge playing." Bono's lyrics are a tongue-in-cheek account of pop culture icons.

"If You Wear That Velvet Dress" features a mellow, dark atmosphere. Marius De Vries played keyboards on this track, contributing to the ambient feel. Mullen uses brush stroke style drums for the most part.[17] When news first broke of U2's work in the studio, it was reported the band were recording a trip hop album; writer Niall Stokes believes that "The Playboy Mansion" comes close to the assertion due to Hooper's heavy hand.[18] Flood stated that Hooper "started things off" but did not finish the track due to his time constraints.[18] Bono reworked this song as a lounge-jazz piece for the 2002 Jools Holland album Small World Big Band Volume Two.[19][20]

"Please" features Bono lamenting The Troubles and the Northern Irish peace process, pleading with the powers that be[citation needed] to "get up off their knees". Mullen uses martial-style drumming, similar to "Sunday Bloody Sunday". Flood put guitar work through the ARP 2600 on the song. He explains, "For ages the rhythm track played all the way through the track. It's a fairly tight groove/bass thing, and then we suddenly decided to drop out the rhythm section in the middle and add a load of strings and these weird synthetic sounds at the end of that break." The single releases and live performances of the song were different from the album version, with more prominent guitar playing and a guitar solo to end the song.

"Wake Up Dead Man" began as an upbeat song from the Achtung Baby sessions in 1991. It evolved into a darker composition during the Zooropa sessions, but it was shelved until Pop. One of the band's darkest songs,[21] "Wake Up Dead Man" features Bono pleading with Jesus to return and save mankind,[22] evident in the lyrics "Jesus / Jesus help me / I'm alone in this world / And a fucked-up world it is too". It is also one of only a few U2 songs to include profanity.

Release

[edit]

Pop was originally scheduled for a November 1996 release date, but after the recording sessions went long, the album was delayed until March 1997. This significantly cut into the band's rehearsal time for the upcoming PopMart Tour that they had scheduled in advance, which impacted the quality of the band's initial performances on tour.[23] Though the band settled on the album name Pop, many working names and proposed titles for the album, including Discola, Miami, Mi@mi, Novelty Act, Super City Mania, YOU2 and Godzilla, went as far as having artwork made for them,[24] while the names Pop for Men and Pop Pour Hommes were also considered.[25] Pop was dedicated to Bill Graham, one of the band's earliest fans who died in 1996, famous for suggesting to Paul McGuinness that he become U2's manager.[26] As with Rattle and Hum, it was also dedicated to the band's production manager Anne Louise Kelly whose dedication message, "4UALKXXXX", is hidden on the playing side of the CD where the matrix number is found.

On 26 October 1996, U2 became one of the earliest bands to fall victim to an internet leak when a Hungary-based fansite leaked clips of "Discothèque" and "Wake Up Dead Man", creating a buzz which built quickly on the internet, as radio stations played the snippets as a means to introduce listeners to the album.[27] The clips were traced back to Polygram, where an executive had shared a VHS tape with previews of the tracks to marketing managers worldwide; one writer said that "from there it got into the hands of a label employee's friend."[27]

Promotion

[edit]On 12 February 1997, two weeks before the album was released, the band held a press conference in the lingerie section of a K-Mart department store in New York City to announce details for the PopMart Tour.[28] On 26 April 1997, American television network ABC aired a one-hour prime time special about Pop and the PopMart Tour, titled U2: A Year in Pop. Narrated by actor Dennis Hopper, the documentary featured footage from the Pop recording sessions, as well as live footage from the opening PopMart show in Las Vegas, which took place the night before.[29] The program received poor reception, ranking at 101 out of 107 programs aired that week, according to Nielsen ratings, and became the lowest rated non-political documentary in the history of the ABC network.[30][31] Despite the low ratings, McGuinness appreciated the opportunity for the band to appear on network television in the first place, stating that the small audience for the television special was still a large audience for the band, as it was much larger than any audience that could be obtained by MTV.[32]

Singles

[edit]Pop featured six international singles, the most the band has released for a single album. "Do You Feel Loved" and "Gone" were also considered for release.[5]

The album's first single, "Discothèque", was released on 3 February 1997 and was a huge dance and airplay success in the U.S. and UK. It also reached No. 1 in the singles charts of most of European countries including the United Kingdom, where it was their third No. 1 single. In the United States, "Discothèque" is notable for being U2's only single since 1991 to crack the top ten of the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at #10. However, the song's dance elements and more humorous video (featuring U2 in a discothèque and even imitating The Village People) limited its appeal. This started a backlash against U2 and Pop, limiting sales, as many fans felt that the band had gone a bit too far over-the-top in the self-mocking and "ironic" imagery.[citation needed]

The follow-up single "Staring at the Sun" was released 15 April 1997 and became a Top 40 success in the U.S., but to a lesser extent, peaking at No. 26 on the Billboard Hot 100. "Last Night on Earth" was released as the third single on 14 July 1997, but did not crack the top 40, peaking at #57. "Please", "If God Will Send His Angels", and "Mofo" were subsequently released as singles, but none reached the Top 100.

The Please: Popheart Live EP, featuring four live tracks from the PopMart Tour, was also released in most regions. In the United States, the four live tracks were instead released on the "Please" single, along with the single version of "Please," itself.

Critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Entertainment Weekly | B[34] |

| Jam! Showbiz | |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| The New Zealand Herald | |

| NME | 8/10[38] |

| Orlando Sentinel | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Spin | 9/10[41] |

| The Sydney Morning Herald | |

Pop initially received favourable reviews from critics. Barney Hoskyns of Rolling Stone gave Pop a four-star rating, praising the band's use of technology on the album: "U2 know that technology is ineluctably altering the sonic surface – and, perhaps, even the very meaning – of rock & roll." The review also stated that U2 had "pieced together a record whose rhythms, textures and visceral guitar mayhem make for a thrilling roller-coaster ride" and that the band had "defied the odds and made some of the greatest music of their lives".[40] David Browne of Entertainment Weekly gave the album a B rating, saying: "Despite its glittery launch, the album is neither trashy nor kitschy, nor is it junky-fun dance music. It incorporates bits of the new technology – a high-pitched siren squeal here, a sound-collage splatter there – but it is still very much a U2 album".[34] Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times rated Pop four-stars-out-of-four, judging the album to benefit "from the tension of... competing influences, sometimes leaning more on the electronic currents, elsewhere showcasing the more melodic and accessible songwriting strengths". He praised the group's musical experimentation, saying, "It is such boldness that has enabled U2 to remain at the creative forefront of pop music for more than a decade."[36] James Hunter of Spin rated the record 9/10, writing, "Pop realizes a symphonic transcendence for which the band's earlier stabs like The Unforgettable Fire could only wish." He added, "They are now experts at wringing genuine emotion, and even a few smirks, out of random sounds, letting their roots filter up from below."[41] Bernard Zuel of The Sydney Morning Herald praised the album's understated tracks and the influence of Howie B, and said that the band avoided making the same mistake as rock counterparts of "trying to slap a traditional bottom-end on top of a metronomic beat and calling it dance". He said that despite not being "the future of rock'n'roll", Pop was "a genuine snapshot of its present by a band bright enough to keep exploring, smart enough not to abandon its past and big enough to make it palatable to radio programmers" resistant to dance music.[42]

Other reviews were more critical. Neil Strauss of The New York Times wrote that "From the band's first album, Boy, in 1980, through The Joshua Tree in 1987, U2 sounded inspired. Now it sounds expensive." He further commented that "U2 and techno don't mix any better than U2 and irony do."[43] Parry Gettelman of the Orlando Sentinel rated the album two stars and found the band's attempt to merge rock music with dance rhythms underwhelming, saying, "U2 lacks the zest for experimentation that has helped make electronic music so appealing to music fans weary of formulaic rock".[39] John Sakamoto of Jam! Showbiz said, "Far from an exercise in daring self-indulgence, Pop is too often guilty of a much more serious offence: not going far enough." He added, "as with so many elements of the ephemeral culture it both disparages and celebrates, it ends up being something considerably less than has been advertised."[35] Village Voice critic Robert Christgau rated it a dud, indicating a bad album unworthy of a review.[44]

Commercial performance

[edit]Pop was initially a commercial success, debuting at number one in 27 countries, including the UK and the US. In its first week on sale, the record sold 349,000 copies in the US.[45] In its second week in the US, the album's sales fell 57 per cent, selling 150,000 copies.[45] The record quickly dropped out of the top ten of the Billboard 200 chart.[46] Pop's lifetime sales are among the lowest in U2's catalogue. It was certified RIAA platinum once, the lowest since the band's album October.[2]

PopMart Tour

[edit]

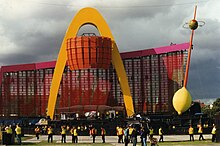

In support of the album, the band launched the PopMart Tour. Consisting of four legs and a total of 93 shows, the tour took the band to stadiums worldwide from April 1997 to March 1998. Much like the band's previous Zoo TV Tour, PopMart was elaborately staged, featured a lavish set, and saw the band embrace an ironic and self-mocking image. The band's performances and the tour's stage design poked fun at the themes of consumerism and embraced pop culture. Along with the reduced rehearsal time that affected initial shows, the tour suffered from technical difficulties and mixed reviews from critics and fans over the tour's extravagance.[47][48][49][50] The PopMart Tour grossed US$171,677,024[51]

Legacy

[edit]Following the PopMart Tour, the band expressed their dissatisfaction with the final product. Between the album's various singles and the band's The Best of 1990–2000 compilation (and disregarding dance remixes),[52] the band re-recorded, remixed, and rearranged "Discothèque", "If God Will Send His Angels", "Staring at the Sun", "Last Night on Earth", "Gone", and "Please". Bono also recorded and issued a drastically different studio version of "If You Wear That Velvet Dress" with Jools Holland. Bono said: "Pop never had the chance to be properly finished. It is really the most expensive demo session in the history of music."[52] Although he reiterated his belief that the album was rushed, the Edge still viewed Pop as a "great record," and said, "I was very proud of it by the end of the tour. We finally figured it out by the time we made the DVD. It was an amazing show that I'm really proud of." In the same interview, Edge also stated: "We started out trying to make a dance-culture record and then realized at the end there are things we can do that no EDM producer or artist can do, so let's try and have it both ways. In that case, we probably went too far in the other direction. We probably needed to allow a bit more of the electronica to survive."[53]

The band took a considerably more conservative, stripped down approach with Pop's follow-up, All That You Can't Leave Behind (2000), along with the Elevation Tour that supported it; All That You Can't Leave Behind featured a "more traditional U2 sound".[52] The few songs from Pop that were performed on the Elevation Tour ("Discothèque", "Gone", "Please", "Staring at the Sun", and "Wake Up Dead Man") were often presented in relatively bare-bones versions. On the Vertigo Tour, songs from Pop were even more rarely played; "Discothèque" was played twice at the beginning of the third leg, while other Pop songs appeared merely as snippets. No Pop songs appeared on the band's U2 360° Tour, though the chorus and guitar riff of "Discotheque" did appear as a regular snippet during the "dance" remix of the song "I'll Go Crazy If I Don't Go Crazy Tonight" late in the tour. U2 did not play a single song from the album on their Innocence + Experience Tour in 2015, although "Mofo" was sampled twice in the earliest tour dates. Pop was the only U2 album that U2 did not play a single song from for the full duration of their tour. "Staring at the Sun" was performed live during U2's 2018 Experience + Innocence Tour, which Andy Greene of Rolling Stone described as "a rare onstage acknowledgment that Pop is a thing that happened."[54] Pop was viewed as U2's "most neglected album" with the band "effectively [disowning] the record by purging its material from setlists."[55][56]

Retrospectively, Pop is viewed in the music press and public as a disappointment. In a 2013 article, Spin was more critical of the album than in the magazine's original review, calling it "U2's nadir period" and a "weirder, bolder, nervier record than its garish exterior would suggest... if you can tune out Bono's mugging, which of course you can't, which was the whole problem. The stupidity of all this subsumed the prescient bravery of it..."[57] Caryn Rose of Vulture said that "A lengthy book could be written about the disaster that was Pop and the subsequent tour."[58] Nonetheless, the album has been praised, including from Elvis Costello who included it in his 2000 list of "500 Albums You Need",[59] and from Hot Press which ranked the album at number 104 on their 2009 list of "The 250 Greatest Irish Albums of All Time".[citation needed] Similarly, in 2003, Slant Magazine included the album in their list "Vital Pop: 50 Essential Pop Albums,"[60] with reviewer Sal Cinquemani saying "the reason why Pop wasn't a bigger hit in the U.S. is a mystery" and said the record was "better (and deeper) than anything on U2's much-ballyhooed 'return' to pop, All That You Can't Leave Behind."[61] Bobby Olivier of Billboard believed that Pop was the band's "last legitimately courageous project," saying that "all we see is a group that chose not to coast."[55] In 2018, BBC included it on its list of "acclaimed albums that nobody listens to any more".[62]

In March 2018, U2 announced that Pop would be reissued and remastered on vinyl alongside Wide Awake in America (1985) and All That You Can't Leave Behind (2000) on 13 April 2018.[63]

Track listing

[edit]All lyrics are written by Bono and the Edge; all music is composed by U2

| No. | Title | Producer | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Discothèque" | Flood | 5:19 |

| 2. | "Do You Feel Loved" |

| 5:07 |

| 3. | "Mofo" | Flood | 5:49 |

| 4. | "If God Will Send His Angels" |

| 5:22 |

| 5. | "Staring at the Sun" |

| 4:36 |

| 6. | "Last Night on Earth" | Flood | 4:45 |

| 7. | "Gone" | Flood | 4:26 |

| 8. | "Miami" |

| 4:52 |

| 9. | "The Playboy Mansion" |

| 4:40 |

| 10. | "If You Wear That Velvet Dress" | Flood | 5:15 |

| 11. | "Please" |

| 5:02 |

| 12. | "Wake Up Dead Man" | Flood | 4:52 |

| Total length: | 60:09 | ||

| No. | Title | Mixed by | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13. | "Holy Joe" (Guilty mix) | Flood | 5:08 |

| Total length: | 65:17 | ||

Notes

- ^[a] – additional production

- The Malaysian edition of Pop has a censored version of "Wake Up Dead Man", omitting the word "fucked (up)" from the song, a rare instance of the band using profanity in their music.

Personnel

[edit]U2

- Bono – lead vocals, guitar

- The Edge – guitar, keyboards, backing vocals

- Adam Clayton – bass guitar

- Larry Mullen Jr. – drums, percussion, programming, drum machine

Production

- Flood – production, keyboards

- Steve Osborne – production, keyboards, engineering, mixing

- Ben Hillier – programming

- Howie B – production, turntables, keyboards, engineering, mixing

- Marius De Vries – keyboards

- Mark "Spike" Stent – engineering, mixing

- Alan Moulder – engineering

- Howie Weinberg – mastering

- Deborah Mannis-Gardner – sample clearance

Design

- Stéphane Sednaoui, Anja Grabert – photography

- Nellee Hooper – photography

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Weekly singles chart

[edit]| Year | Song | Peak | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRE [99] |

AUS [100] |

BE (Fl) [100] |

CAN [101] |

UK [102] |

US [103] | ||

| 1997 | "Discothèque" | 1 | 3 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| "Staring at the Sun" | 4 | 23 | 46 | 2 | 3 | 26 | |

| "Last Night on Earth" | 11 | 32 | 29 | 4 | 10 | 57 | |

| "Please" | 6 | 21 | 31 | 10 | 7 | — | |

| "Mofo" | — | 35 | — | — | — | — | |

| "If God Will Send His Angels" | 11 | — | — | — | 12 | — | |

| 2001 | — | — | — | 26 | — | — | |

| "—" denotes a release that did not chart. | |||||||

Certifications and sales

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[104] | Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[105] | Platinum | 70,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[106] | Platinum | 50,000* |

| Belgium (BEA)[107] | Platinum | 50,000* |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[108] | Gold | 100,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[109] | 3× Platinum | 300,000^ |

| Finland (Musiikkituottajat)[110] | Gold | 32,952[110] |

| France (SNEP)[111] | Platinum | 300,000* |

| Germany (BVMI)[112] | Gold | 250,000^ |

| Hong Kong (IFPI Hong Kong)[113] | Platinum | 20,000* |

| Italy (FIMI)[114] | 3× Platinum | 400,000[115] |

| Japan (RIAJ)[116] | Platinum | 200,000^ |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[117] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[118] | 2× Platinum | 30,000^ |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[119] | Platinum | 50,000* |

| Poland (ZPAV)[120] | Gold | 50,000* |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[121] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| Sweden (GLF)[122] | Gold | 40,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[123] | Platinum | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[124] | Platinum | 300,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[126] | Platinum | 1,500,000[125] |

| Summaries | ||

| Europe (IFPI)[127] | 2× Platinum | 2,000,000* |

| Worldwide | — | 5,000,000[128] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

- ^ Jack, Malcolm (2 August 2018). "Vorsprung durch technik – revisiting U2's last truly great album 25 years on". The Big Issue. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Gold and Platinum Database Search". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ * Fallon, BP (1994). U2, Faraway So Close. London: Virgin Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-86369-885-9.

- ^ "Books by BP". BP Fallon. Archived from the original on 30 October 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Tingen, Paul (July 1997). "Flood & Howie B: Producing U2's Pop". Sound on Sound. Vol. 12, no. 9. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ a b McCormick (2006), p. 265.

- ^ a b c McCormick (2006), p. 262.

- ^ a b McCormick (2006), p. 266.

- ^ "U2 : Max Masters : About Pop". YouTube. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McCormick (2006), p. 270.

- ^ "Discography > Albums > Pop". U2. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Graham, Bill; van Oosten de Boer (2004). U2: The Complete Guide to their Music. London: Omnibus Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 0-7119-9886-8.

- ^ a b D. Luerssen (2010), 294

- ^ a b D. Luerssen (2010), 295

- ^ D. Luerssen (2010), 296

- ^ Unterberger, Andrew (16 October 2007). "Playing God U2 – Poopropa". Stylus Magazine. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ "Original Pop version of "If You Wear That Velvet Dress"". Youtube.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b Stokes (1997), p. 131.

- ^ "Amazon listing of the Holland/Bono version". Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "The Jools Holland/Bono version of "If You Wear That Velvet Dress"". Youtube.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "U2: Discographically Speaking". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012.

- ^ Browne, David (7 March 1997). "RATTLE AND HYMN (1997)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ "U2 Set to Re-Record Pop". contactmusic.com. Retrieved 31 October 2006.

- ^ Stealing Hearts from a Travelling Show: The Graphic Design of U2 book, page 75

- ^ Stokes (1997), p. 123.

- ^ "U2: U2faqs.com - History FAQ - Let's Go Shopping - Pop to the Best of 1980-1990". Archived from the original on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ a b D. Luerssen (2010), 293

- ^ Mehle, Michael (16 February 1997). "Attention popmart shoppers – u2 is coming to your stadium". Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ Gallo, Phil (24 April 1997). "U2: A Year in Pop". Variety. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Menconi, David (28 May 1997). "Rains, Apathy Cancel U2 in Raleigh" (reprint). The News & Observer. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ de la Parra (2003), p. 195.

- ^ Taylor, Tess (1 April 1997). "U2's Paul McGuinness: A Manager and a Gentleman". National Association of Record Industry Professionals. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Pop Review". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ a b Browne, David (7 March 1997). "Music Review: Pop". Entertainment Weekly. No. 369. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ a b Sakamoto, John (21 February 1997). "U2 Pop out un-rock-like album". Jam! Showbiz. CANOE. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ a b Hilburn, Robert (2 March 1997). "Snap, Crackle, 'Pop'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Baillie, Russell (28 February 1997). "Album review: Pop". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ "Pop: Kitsch of Distinction". NME. 1 March 1997.

- ^ a b Gettelman, Parry (7 March 1997). "David Bowie, U2". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ a b Hoskyns, Barney (20 March 1997). "Music Reviews: Pop". Rolling Stone. No. 756. pp. 81–83. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ a b Hunter, James (April 1997). "Spins – Platter du Jour: U2 – Pop". Spin. Vol. 1, no. 13.

- ^ a b Zuel, Bernard (7 March 1997). "Sounds Right – Feature Album: U2 – Pop (Island/Mercury)". The Sydney Morning Herald. sec. Metro, p. 9.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (6 March 1997). "Fleeing a certain sound, and seeking it". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (2000). "CG Book '90s: U". Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. Macmillan. ISBN 0312245602. Retrieved 30 March 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ a b "U2's "Pop" plunges in second week". Archived from the original on 27 October 2004. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Kassulke, Natasha (24 June 1997). "Pop Show U2 Hits Camp Randall With Its Disco-Style Supermarket Offering Plenty of Cheesy Kitsch". Wisconsin State Journal.

- ^ "Spinal Tap Moments: Rock 'n' Roll's 15 Most Embarrassing Stage Antics". Spinner.com 3x3. AOL. Archived from the original on 18 January 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

- ^ Mühlbradt, Matthias; Stieglmayer, Martin. "1998-02-27: Sydney Football Stadium, Sydney – New South Wales". Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- ^ Rowlands, Paul (December 2006). "Nine Things You Possibly Didn't Know About U2 and Japan". Interference.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- ^ Mühlbradt, Matthias; Stieglmayer, Martin (29 May 1997). "1997-05-29: Carter-Finley Stadium, Raleigh – North Carolina". Retrieved 2 April 2006.

- ^ de la Parra (2003), p. 221

- ^ a b c Greene, Andy (14 March 2017). "U2's 'Pop': A Reimagining of the Album 20 Years Later". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ Greene, Andy (18 September 2017). "The Edge on U2's 'Songs of Experience,' Bono's 'Brush With Mortality'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Greene, Andy (3 May 2018). "U2 Dig Deep at Transcendent 'Experience' Tour Opener in Tulsa". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ a b Olivier, Bobby (3 March 2017). "The 'Pop' Enigma: Revisiting U2's Most Misunderstood Album 20 Years Later". Billboard. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Schonfeld, Zach (5 December 2017). "What is the Best U2 Album? Every Record Ranked from Boy to Songs of Experience". Newsweek. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Harvilla, Rob (25 October 2013). "Inorganic at the Disco: 40 Rock Bands Who Beat Arcade Fire to the Dance Floor – U2, Pop (1997)". Spin. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Rose, Caryn (12 December 2017). "All 218 U2 Songs, Ranked From Worst to Best". Vulture. New York. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Costello, Elvis. "Elvis Costello's 500 Must-Have Albums, from Rap to Classical". vanityfair.com. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Vital Pop: 50 Essential Pop Albums – Feature – Slant Magazine". slantmagazine.com. 30 June 2003. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "U2 Pop – Album Review – Slant Magazine". slantmagazine.com. 14 April 2004. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Hewitt, Ben (9 February 2018). "7 acclaimed albums that no one listens to anymore". BBC. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Moore, Sam (4 March 2018). "U2 are Reissuing Three Classic Records on Vinyl". NME. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ allmusic.com

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – U2 – Pop". Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – U2 – Pop" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – U2 – Pop" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – U2 – Pop" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "U2 Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ a b c "Hits of the World (Continued)". Billboard. 29 March 1997. p. 53. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – U2 – Pop" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Hits of the World – Eurochart/Ireland". Billboard. 22 March 1997. p. 67. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "U2: Pop" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – U2 – Pop". Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – U2 – Pop" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 1997. 11. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Hits of the World – Italy/Japan". Billboard. 22 March 1997. p. 66. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Charts.nz – U2 – Pop". Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – U2 – Pop". Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – U2 – Pop". Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – U2 – Pop". Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "U2 Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "ARIA Top 100 Albums for 1997". Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 1997" (in German). austriancharts.at. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 1997 – Albums" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Rapports Annuels 1997 – Albums" (in French). Ultratop. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Albums 1997" (in Dutch). dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Year in Focus – European Top 100 Albums 1997" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 14, no. 52. 27 December 1997. p. 7. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Tops de l'Année – Top Albums 1997" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 1997". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Anexo 2. Los 50 Títulos Con Mayores Ventas en las listas de ventas de AFYVE en 1997" (in Spanish). SGAE. p. 62. Retrieved 9 February 2021.Open the 2000 directory, click on "entrar" (enter) and select the section "Música grabada".

- ^ "Årslista Album (inkl samlingar), 1997" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 1997" (in German). hitparade.ch. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 1997". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1997". Billboard. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Search the charts". Irishcharts.ie. Retrieved 29 October 2009. Note: U2 must be searched manually

- ^ a b "1ste Ultratop-hitquiz". Ultratop. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ^ "U2: Charts and Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 21 November 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "U2 singles". Everyhit.com. Retrieved 29 October 2009. Note: U2 must be searched manually.

- ^ "U2 Chart History: Hot 100". Billboard. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ "Discos de Oro y Platino – U2" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on 31 May 2011.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 1997 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- ^ "Austrian album certifications – U2 – Pop" (in German). IFPI Austria.

- ^ "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 1997". Ultratop. Hung Medien.

- ^ "Brazilian album certifications – U2 – Pop" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – U2 – Pop". Music Canada.

- ^ a b "U2" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland.

- ^ "French album certifications – U 2 – Pop" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (U2; 'Pop')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie.

- ^ "IFPIHK Gold Disc Award − 1997". IFPI Hong Kong. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "U2: terzo disco di platino per Pop" [U2: 3× Platinum disc for Pop] (in Italian). Adnkronos. 19 March 1997. Archived from the original on 16 October 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Musica: Pino Daniele E' Il Re Delle Vendite 1997" (in Italian). Adnkronos. 29 December 1997. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Japanese album certifications – U2 – Pop" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Retrieved 11 June 2019. Select 1997年3月 on the drop-down menu

- ^ "Dutch album certifications – U2 – Pop" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Enter Pop in the "Artiest of titel" box. Select 1997 in the drop-down menu saying "Alle jaargangen".

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – U2 – Pop". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ "IFPI Norsk platebransje Trofeer 1993–2011" (in Norwegian). IFPI Norway.

- ^ "Wyróżnienia – Złote płyty CD - Archiwum - Przyznane w 1997 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. 18 March 1997.

- ^ Salaverrie, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (PDF) (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Madrid: Fundación Autor/SGAE. p. 945. ISBN 84-8048-639-2. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ "Guld- och Platinacertifikat − År 1987−1998" (PDF) (in Swedish). IFPI Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2011.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('Pop')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien.

- ^ "British album certifications – U2 – Pop". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Newman, Melinda (27 November 2004). "Bombs Away!". Billboard. Vol. 116, no. 48. p. 64. Retrieved 9 November 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "American album certifications – U2 – Pop". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards – 1997". International Federation of the Phonographic Industry.

- ^ Bream, John (15 July 2011). "Oct 26, 1997: Bono sounds off on the PopMart tour". Star Tribune. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

Bibliography

- D. Luerssen, John (2010). U2 FAQ. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-997-8.

- de la Parra, Pimm Jal (2003). U2 Live: A Concert Documentary (Updated ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-9198-9.

- Stokes, Niall (1997). U2: The Stories Behind Every U2 Song. New York, NY: Carlton Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-84732-287-6.

- U2 (2006). McCormick, Neil (ed.). U2 by U2. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-719668-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- Pop at U2.com