Mexican muralism

Mexican muralism refers to the art project initially funded by the Mexican government in the immediate wake of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) to depict visions of Mexico's past, present, and future, transforming the walls of many public buildings into didactic scenes designed to reshape Mexicans' understanding of the nation's history. The murals, large artworks painted onto the walls themselves had social, political, and historical messages. Beginning in the 1920s, the muralist project was headed by a group of artists known as "The Big Three" or "The Three Greats".[1] This group was composed of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Although not as prominent as the Big Three, women also created murals in Mexico. From the 1920s to the 1970s, murals with nationalistic, social and political messages were created in many public settings such as chapels, schools, government buildings, and much more. The popularity of the Mexican muralist project started a tradition which continues to this day in Mexico; a tradition that has had a significant impact in other parts of the Americas, including the United States, where it served as inspiration for the Chicano art movement.

Background

[edit]

Mexico has had a tradition of painting murals, starting with the Olmec civilization in the pre Hispanic period and into the colonial period, with murals mostly painted to evangelize and reinforce Christian doctrine.[2] The modern mural tradition has its roots in the 19th century, with this use of political and social themes. The first Mexican mural painter to use philosophical themes in his work was Juan Cordero in the mid-19th century. Although he did mostly work with religious themes such as the cupola of the Santa Teresa Church and other churches, he painted a secular mural at the request of Gabino Barreda at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria (since disappeared).[3]

The latter 19th century was dominated politically by the Porfirio Díaz regime. This government was the first to push for the cultural development of the country, supporting the Academy of San Carlos and sending promising artists abroad to study. However, this effort left out indigenous culture and people, with the aim of making Mexico like Europe.[2] Gerardo Murillo, also known as Dr. Atl, is considered to be the first modern Mexican muralist with the idea that Mexican art should reflect Mexican life.[4] Academy training and the government had only promoted imitations of European art. Atl and other early muralists pressured the Diaz government to allow them to paint on building walls to escape this formalism.[5] Atl also organized an independent exhibition of native Mexican artists promoting many indigenous and national themes along with color schemes that would later appear in mural painting.[6] The first modern Mexican mural, painted by Atl, was a series of female nudes using "Atlcolor", a substance Atl invented himself, very shortly before the beginning of the Mexican Revolution.[7] Another influence on the young artists of the late Porfirian period was the graphic work of José Guadalupe Posada, who mocked European styles and created cartoons with social and political criticism.[6] Critiquing the political policies of the Díaz dictatorship through art was popularized by Posada. Posada influenced muralists to embrace and continue criticizing the Díaz dictatorship in their works. The muralists also embraced the characters and satire present in Posada's works.[8]

The Mexican Revolution itself was the culmination of political and social opposition to Porfirio Díaz policies. One important oppositional group was a small intellectual community that included Antonio Curo, Alfonso Reyes and José Vasconcelos. They promoted a populist philosophy that coincided with the social and political criticism of Atl and Posada and influenced the next generation of painters such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.[9]

These ideas gained power as a result of the Mexican Revolution, which overthrew the Díaz regime in less than a year.[9] However, there was nearly a decade of fighting among the various factions vying for power. Governments changed frequently with a number of assassinations, including that of Francisco I. Madero who initiated the struggle. It ended in the early 1920s with one-party rule in the hands of the Álvaro Obregón faction, which became the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI).[2] During the Revolution, Atl supported the Carranza faction and promoted the work of Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros, who would later be the founders of the muralism movement. Through the war and until 1921, Atl continued to paint murals among other activities including teaching the Mexico's next generation of artists and muralists.[7]

Mural movement

[edit]

In 1921, after the end of the military phase of the Revolution, General Alvaro Obregón rose to power.[10] In the aftermath of the Revolution, Mexico had entered a transition from an "oligarchic" state to a "modernizing" state, one that favored urbanization and the bourgeoisie citizens of society. As the country underwent this reformation, General Obregón realized that the reconstruction of a post-revolution Mexico would require a comprehensive alteration of symbols associated with Mexican identity on both cultural and political grounds.

Shortly after the wars end, Obregón appointed José Vasconcelos to act as the Secretaría de Educación Pública, or Minister of Public Education. In his efforts to help raise a sense of nationalism and promote the inclusion of the masses in political and social ideologies, it was Vasconcelos' idea to have a government-backed mural project.[2] His time as secretary was short but it set how muralism would develop. His image was painted on a tempera mural in 1921 by Roberto Montenegro, but this was short lived. His successor at the Secretaría de Educación Pública ordered it painted out.[2]

Parallel to the utilization of murals during the pre-Hispanic and the colonial period, the murals were not to simply satisfy aesthetic purposes, but to promote certain social ideals in the Mexican people.[10][2][5] These ideals or principles were to glorify the Mexican Revolution and the identity of Mexico as a mestizo nation.[2] This placed great emphasis on the pride associated with the indigenous culture of Mexico. The government began to hire the country's best artists to paint murals, calling some of them home from their time in Europe, including Diego Rivera.[9] These initial muralists included Dr. Atl, Ramón Alva de la Canal, Federico Cantú and others but the main three artists that spearheaded the muralist project were David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera. These three artists, commonly known as "Los Tres Grandes", claimed to act as both the "'voice and vote' of the Mexican national consciousness," calling themselves "guardians of the national soul".[10] The muralists differed in style and temperament, but all believed that art was for the education and betterment of the people. This was behind their acceptance of these commissions as well as their creation of the Syndicate of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors.[9]

The first government sponsored mural project was on the three levels of interior walls of the old Jesuit institution Colegio San Ildefonso, at that time used for the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria.[5][6] Most of the murals in the Escuela National Preparatoria, or National Preparatory School, were done by José Clemente Orozco with themes of a mestizo Mexico, the ideas of renovation, and the reality of the Revolution's violence.[5] Also at the National Preparatory School, Fernando Leal painted Los Danzantes de Chalma (Dancers of Chalma) no earlier than 1922. Opposite that mural, Jean Charlot painted La conquista de Tenochtitlán (Conquest of Tenochtitlan) by Jean Charlot—invited by Leal.[11] Rivera also contributed his first-ever government-backed mural to the National Preparatory School in 1922 called Creation, functioning as an allegorical depiction of the holy trinity representing love, hope, and faith.[12]

The movement was strongest from the 1920s to the 1950s, which corresponded to the country's transformation from a mostly rural and mostly illiterate society to an industrialized one. While today, Murals are seen as symbols of Mexican identity, at the time they were controversial, especially those with socialist messages plastered on centuries-old colonial buildings.[5] One of the basic underpinnings of the nascence of a post revolutionary Mexican art was that it should be public, available to the citizenry and above all not the province of a few wealthy collectors. The great societal upheaval made the concept possible as well as a lack of relatively wealthy middle class to support the arts.[2] On this, the painters and the government agreed. One other point of agreement was that artists should have complete freedom of expression. This would lead to another element added to the murals over their development.

In addition to the original ideas of a reconstructed Mexico and the elevation of Mexico's indigenous and rural identity, many of the muralists, including the three main painters, also included elements of Marxism, especially in trying to frame the struggle of the working class against oppression.[2][5] This struggle, which had been going on since the sixteenth century, along with class, culture, and race conflicts were interpreted by muralists.[13]

The inception and early years of Mexico's muralist movement are often considered the most ideologically pure and untainted by contradictions between socialist ideals and government manipulation. This initial phase is referred to as the "heroic" phase while the period after 1930 is the "statist" phase with the transition to the latter phase caused by José Vasconcelos's resignation in 1924.[14] Scholar Mary Coffey describes those who "acknowledge a change but refrain from judgment about its consequences" as taking the soft line and those who see all murals after 1930 as "propaganda for a corrupt state" as taking a hard line.[14] Another stance is that the evolution of Mexican muralism as having an uncomplicated relationship with the government and as an accurate reflection of avant-garde and proletariat sentiments. However, hard liners see the movement as complicit in the corrupt government's power consolidation under the guise of a socialist regime.[14]

Art historian Leonard Folgarait has a slightly different view. He marks 1940 as the end of the post-revolutionary period in Mexico as well as the renaissance era of the muralist movement.[15] The conclusion of the Lázaro Cárdenas administration (1934 – 1940) and the beginning of the Manuel Avila Camacho (1940 – 1946) administration saw the rise of an ultraconservative Mexico.[15] The country's policy was aimed at maintaining and strengthening a capitalist society.[15] Mural artists like the Big Three spent the post-revolutionary period developing their work based on the promises of a better future, and with the advent of conservatism they lost their subject and their voice.

The Mexican government began to distance itself from mural projects and mural production became relatively privatized. This privatization was a result of patronage from the growing national bourgeoisie. Murals were increasingly contracted for theaters, banks, and hotels.[16]

Mexican School of Painting and Sculpture

[edit]

Mexican populist art production from the 1920s to the 1950s is often grouped under the name of Escuela Mexicana de Pintura y Escultura,[17] coined in the 1930s by art historians and critics. The term is not well-defined as it does not distinguish among some important stylistic and thematic difference, there is no firm agreement which artists belong to it nor if muralism should be considered part of it or if these artworks should be left separate from the more well-known murals of the movement.[18][19] It is not a school in the classic sense of the word as it includes work by more than one generation and with different styles that sometimes clash. However, it does involve a number of important characteristics.

Mexican School mural painting was a combination of public ideals and artistic aesthetics "positioned as a constituent of the official public sphere."[20] Three formal components of official Mexican muralism are defined as: 1) Direct participation in official publicity and discourse[21] 2) Reciprocal integration of the visual discourse of the mural to an array of communicative practices participant in defining official publicity (including a variety of scriptural genres, but also public speech, debate and provocative public "event")[21] 3) The development and public thematizing of a social-realist aesthetic (albeit multiform in character) as the visual register for the public sense of the mural work and as the doxic, or unquestioned, limits for public dispute over the representational space of the mural image[21] Most painters in this school worked in Mexico City or other cities in Mexico, working almost uninterrupted on projects and/or as teachers, generally with support of the government. Most were concerned with the history and identity of Mexico and politically active. Most art from this school was not created for direct sale but rather for diffusion in both Mexico and abroad. Most were formally trained, often studying in Europe and/or in the Academy of San Carlos.[19]

A large quantity of murals were produced in most of the country from the 1920s to 1970, generally with themes related to politics and nationalism focused often on the Mexican Revolution, mestizo identity and Mesoamerican cultural history.[2] Scholar Teresa Meade states that "indigenismo; the glorification of rural and urban labor and the working man, woman, and child; social criticism to the point of ridicule and mockery; and denunciation of the national, and especially, international ruling classes" were also themes present in the murals at this time.[22] These served as a form of cohesion among members of the movement.[5] The political and nationalistic aspects had little directly to do with the Mexican Revolution, especially in the later decades of the movement. The goal was more to glorify the revolution itself, highlighting its results as a means to legitimatize the post Revolution government.[2] The other political orientation was that of Marxism, especially class struggle. This political group grew strongest in the early movement with Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros all of which being openly avowed communists. The political messages became less radical but they remained firmly to the left.[2]

Much of the mural production glorified indigenismo, or the indigenous aspect of Mexican culture as artists of the movement collectively considered it to be an important factor in the reconstruction of a more modern Mexico. These themes were added with the idea of reexamining the country's history from a different perspective. One other aspect that most of the muralists shared was a rejection of the idea that art was only for the elite, but rather as a benefit for the masses.[5] The various reasons for the focus on ancient Mesoamerica may be divided into three basic categories: the desire to glorify the accomplishments of the perceived original cultures of the Mexican nation; the attempt to locate residual pre-Hispanic forms, practices, and beliefs among contemporaneous indigenous peoples; and the study of parallels between the past and present. Within this last context, the torture of Cuauhtémoc was painted by Siqueiros in 1950 in the Palacio Nacional, one of his few depictions of indigenous cultures of any period.[23]

Many of the murals from the muralist project took on monumental status because of where they were situated, mostly on the walls of colonial era government buildings and the themes that were painted.[5] The mural painters of Mexico freely shared ideas and techniques in public spaces in order to capture the attention of the masses. While many of the themes are shared between artists, the work of each artist was distinctive as the government did not impose a set style. These artists were so distinctive that they can generally be deduced without needing to look at the artist's signatures.[9] Techniques used in the production of these murals also included the revival of old techniques such as the fresco, painting on freshly plastered walls and encaustic or hot wax painting.[5][6] Others used mosaics and high fire ceramics, as well as metal parts, and layers of cement.[5] The most innovative of the artists was Siqueiros, who worked with pyroxene, a commercial enamel, and Duco (used to paint cars), resins, asbestos and old machinery, and was one of the first to use airbrush for artistic purposes. He pored, sprayed, dripped and splattered paint for the effects they created haphazardly.[9]

Artists

[edit]Los Tres Grandes (The Three Greats)

[edit]

By far, the three most influential muralists from the 20th century are Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros, called "los tres grandes" (the three great ones).[4][5] All believed that art was the highest form of human expression and a key force in social revolution.[4] Their work was the driving force that defined the movement originally set into motion by Vasconcelos. It created a mythology around the Mexican Revolution and the Mexican people which is still influential to this day, as well as promote Marxist ideals. At the time the works were painted, they also served as a form of catharsis over what the country had endured during the war.[5] However, the three were different in their artistic expression. To summarize the general types of contributions the Three Greats made, Rivera's works were utopian and idealist, Orozco's were critical and pessimistic, while the most radical of the three was Siqueiros, who heavily focused on a scientific future.[5][9] Their different points of view were shaped by their own personal experiences with Mexican Revolution. In Rivera case, he was in Europe during the revolution and had never experienced the horrors of the war. While never experiencing the war first hand, his art primarily focused on what he perceived to be the social benefits from the revolution.[5] Orozco and Siqueiros, on the other hand, both fought in the war, which subsequently resulted in a more pessimistic approach to their artwork when depicting the revolution; with Siqueros' artwork being notably more radical and focused on portraying a scientific future.[2][5]

Of the three, Diego Rivera was the most traditional in terms of painting styles, drawing heavily from European modernism. In his narrative mural images, Rivera incorporated elements of cubism[20] His themes were Mexican, often scenes of everyday life and images of ancient Mexico.[12] He originally painted this in bright colors in the European style but modified it to more earthy tones to imitate indigenous murals. His greatest contribution is the promotion of Mexico's indigenous past into how many people both inside and outside of the country view it.[6][9] One of the most prominent examples of this is Rivera's contribution to the Mexican National Palace, translated as The History of Mexico, which he worked on from1929-1935.[12]

José Clemente Orozco's art also began with a European style of expression; however, his art developed into an angry denunciation of oppression especially by those he considered to be of the evil and brutal higher economic class.[6] His work was somber and dire, with emphasis on human suffering and fear of the technology of the future, intent on displaying the reality of the war.[9] His work shows an "expressionist use of color, slashing lines, and parodic distortions of the human figure."[24] Like most other muralists, Orozco condemned the Spanish as destroyers of indigenous culture, but he did have kinder depictions such as that of a Franciscan friar tending to an emaciated indigenous period.[6] Unlike other artists, Orozco never glorified the Mexican Revolution, having fought in it, but rather depicted the horrors of this war. It caused many of his murals to be heavily criticized and even defaced.[9]

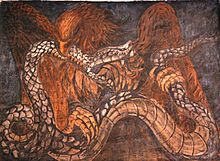

David Alfaro Siqueiros was the youngest and most radical of the three. He joined the Venustiano Carranza army when he was eighteen and experienced the Revolution from the front lines.[5][6] Although all three muralists were communists, Siqueiros was the most dedicated, as evidenced by his portrayals of the proletarian masses. His work is also characterized with rapid, sweeping, bold lines and the use of modern enamels, machinery and other elements related to technology. His style showed a "futurist blurring of form and technique." His fascination with technology as it relates to art was exemplified when he emphasized the mass communications visual technology of photograph and motion picture in his eventual movement toward neorealism.[24] His radical politics made him unwelcome in Mexico and the United States, so he did much of his work in South America.[6][9] However, his masterpiece is considered to be the Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros, located in Mexico City.[2]

While Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros are usually regarded as the most influential mural artists of the period, Rufino Tamayo also contributed to the movement of the 1920s.[25][26] Tamayo was younger than the Big Three and he often argued against their attitudes. He argued against their isolationist work after his art studies in Europe where he became heavily influenced by post World War II abstractions. He believed that the Mexican Revolution would ultimately harm Mexico due to the progressive attitudes that were arising. When he returned to Mexico after staying in Europe, he wanted his artwork to express pre-Conquest art but in his own abstract style.[27]

Tamayo was heavily influenced by the early pre-Columbian history of Mexico and it is evident in his piece titled "Nacimiento de Nuestra Nacionalidad".[25] He expresses the violence that was used during the Spanish conquest of native Mexicans. The center shows a human figure holding a mechanical weapon, sitting atop a horse and surrounded by a glowing light which depicted a 'godlike' Spanish conquistador. The horse is shaped like a majestic creature because it was a creature that the native Mexicans had never seen before.[25] Overall, this piece offers an immense amount of imagery and is a reflection of the initial defeat of Mexican nationalism and shows the traumatic and oppressive history. Tamayo was proud of his Mexican roots and expressed his nationalism in a more traditional way than Rivera or Siqueiros. His focus was on accepting both his Spanish and native background and ultimately expressing the way he felt through the colors, shapes and culture in a modern abstract way.[26] Ultimately, Tamayo wanted the Mexican people to not forget their roots; it shows why he was so persistent in using inspiration from the pre-Columbian period as well as incorporating his own perspective of the Mexican Revolution.[28]

Revolutionary themes and ideas

[edit]One of the best examples of Rivera's perspective on the revolution can be seen in his mural at the chapel of the Chapingo Autonomous University (murals)[6] The most dominant artwork in this mural is The Liberated Earth 1926-27 Fresco which depicts Rivera's second wife, Guadalupe Marín, Voluptuous and recumbent, hand held aloft, she symbolizes the fertility of the land, and exudes a dominant, life-affirming energy which triumphs artistically against the injustices depicted elsewhere.[29] This artwork sits as the final site to be seen, representing Rivera's view of what the Mexican revolution would bring – a free and productive earth in which natural forces being able to be harnessed for the benefit of man. To say Liberated Earth acts as a fictional finalism of a social Mexico would be supported by the preceding artworks in Chapingo Chapel. These prior artworks showcase the evolution of the agrarian movement paralleled with the evolution of Earth, both timelines of events being heavily reflective of Rivera's own positive views.[12]

Orozco's view point on the Mexican Revolution can be seen in his mural The Trench (1922-1924), Mexico that can be found at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria. The dynamic lines and diluted color palette exemplify the dismal tone Orozco sets to exemplify his negative attitude towards the revolution. Contrary to many other revolutionary artists, one can also note how Orozco leaves the faces of the soldiers hidden, further displaying his own ideologies about the war. This form of anonymity functions as commentary towards the war and the soldiers that fought for the revolution – that they will be forgotten, despite their courageous sacrifice in hopes of a brighter future. From this more violent and realistic representation of the revolution, Orozco's aim is to get viewers to question if the revolutionary war was worth the sacrifices made.[16] These artworks sparked massive controversy, even leading to the defacing of this mural, but was then later repainted in 1926.[30]

Siqueiros brought a nuance to the idea of the Mexican Revolution. Although he held a radically negative opinion towards the revolution, he also depicted images of the scientific future while the other two artists' primary focus was on their experience and view on the revolution. In 1939 Siqueros, in collaboration with a group of other revolutionary artists, constructed a mural at the Electrical Workers Union Building titled Portrait of the Bourgeoise (1939), Mexico City Mexico. Together, these artists aimed to present their belief that the violence of the revolutionary war stemmed from the utilization of the flaw economic system they knew as capitalism, used as a tool of perpetuating the control of fascist leaders.[16] This piece of art demonstrates the horrors of war, the artists' own negative views toward the role of capitalism during the Revolution, and how the proletariat Mexican citizens were being overlooked and taken advantage of by the Bourgeoise. The emotional toll of war is also highlighted by the reaction of a frightened, on-looking mother and child pair, further reflecting the artist's own reactions toward capitalism. Among all of the pessimistic imagery is also a symbol of hope manifested by a lone man dressed in the clothing of a guerrilla fighter. He's seen grasping a rifle pointed towards Bourgeoise leaders present during the revolution. This symbolizes a promising future in which Mexico overcomes the obstacles faced in the revolution and embraces technology, as seen in the depictions of electrical towers at the top of the mural.[31]

Political expression

[edit]The Big Three struggled to express their leftist leanings after the initial years painting murals under government supervision. These struggles with the post-revolution government lead the muralists to create a union of artists and produce a radical manifesto. José Vasconcelos, the Secretary of Public Education under President Álvaro Obregón (1920–24) contracted Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco to pursue painting with the moral and financial support of the new post-revolutionary government.[32] Vasconcelos, while seeking to promote nationalism and "la raza cósmica," seemed to contradict this sentiment as he guided the muralists to create works in a classic, European style. The murals became a target of Vasconcelos's criticism when the Big Three departed from classical proportion and figure. Siqueiros was dissatisfied with the incongruity between the murals and the revolutionary concerns of the muralists, and he advocated discussion among the artists of their future works.

In 1922 the muralists founded the Union of Revolutionary Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors of Mexico. The Union then released a manifesto listing education, art of public utility, and beauty for all as the social goals of their future artistic endeavors.[33]

Influence

[edit]

After nearly a century since the beginning of the movement, Mexican artists still produce murals and other forms of art with the same "mestizo" message. Murals can be found in government buildings, former churches and schools in nearly every part of the country.[2][34] One recent example is a cross cultural project in 2009 to paint a mural in the municipal market of Teotitlán del Valle, a small town in the state of Oaxaca. High school and college students from Georgia, United States, collaborated with town authorities to design and paint a mural to promote nutrition, environmental protection, education and the preservation of Zapotec language and customs.[34]

Mexican muralism brought mural painting back to the forefront of Western art in the 20th century with its influence spreading abroad, especially promoting the idea of mural painting as a form of promoting social and political ideas.[5] It offered an alternative to non-representational abstraction after World War I with figurative works that reflect society and its immediate concerns. While most Mexican muralists had little desire to be part of the international art scene, their influence spread to other parts of the Americas. Muralists influenced by Mexican muralism include Carlos Mérida of Guatemala, Oswaldo Guayasamín of Ecuador and Candido Portinari of Brazil.[6]

Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros all spent time in the United States. Orozco was the first to paint murals in the late 1920s at Pomona College in Claremont, California, staying until 1934 and becoming popular with academic institutions.[2][4] During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration employed artists to paint murals, which paved the way for Mexican muralists to find commissions in the country.[4] Rivera lived in the United States from 1930 to 1934. During this time, he put on an influential show of his easel work at the Museum of Modern Art.[2][4] The success of Orozco and Rivera prompted U.S. artists to study in Mexico and opened doors for many other Mexican artists to find work in the country.[2] Siqueiros did not fare as well. He was exiled to the US from Mexico in 1932, moving to Los Angeles. During this time, he painted three murals, but they were painted over.[2][4] The only one of the three to survive, América Tropical (full name: América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos, or Tropical America: Oppressed and Destroyed by Imperialism[35]), was restored by the Getty Conservation Institute and the América Tropical Interpretive Center opened to provide public access.[36]

The concept of mural as political message was transplanted to the United States, especially in the former Mexican territory of the Southwest. It served as inspiration to the later Chicano muralism but the political messages are different.[2] Revolutionary Nicaragua developed a tradition of muralism during the Sandinista period.[37]

Women of Mexican muralism

[edit]Aurora Reyes Flores, the first woman muralist

[edit]Aurora Reyes Flores was a political activist, teacher, and the first recognized female Mexican muralist. She focused on highlighting problems of those that she considered unprotected.[38][39] Her first mural, "Atentado a Las Maestras Rurales" (Attack on Rural Teachers), depicts a woman who is being dragged by the hair by a man who is also tearing up a book with his other hand. Another man, whose face is covered by the large sombrero on his head, also begins beating the woman with the butt of his rifle. Behind a door stand three children witnessing the violence take place as they look on in utter shock and disbelief. The mural reflected Reyes' concerns with the education system and the struggle to improve social conditions for working women.[38]

Elena Huerta Muzquiz, created the largest mural in Mexico by a woman

[edit]Elena Huerta's 450 square meter work is the largest mural created by a woman in Mexico, taking her two years to complete.[40] Located in Saltillo, Mexico, the mural shows two different scenes. One scene depicts the independence of Mexico in 1810 with Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, while the other scene shows Hidalgo alongside contemporary independence leaders who contributed to the independence movements of Mexico.[41]

Huerta was not only known for her artwork, but also for her literary works, as she was a writer and feminist. In her lifetime, she was able to create only three murals. She captured the true essence of the Mexican Muralist movement through her passion and ability to keep Mexican culture viable.[38]

As Rina Lazo worked alongside Rivera, she became heavily influenced by his artwork and even helped him on one of the most outstanding murals of the Mexican Revolution: "Sueno de Una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central" (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park).[38] She became Rivera's assistant for a total of ten years, right up until his death in 1957. However, she also worked on her own pieces and ultimately had to navigate through her own personal struggles on how to fully depict Mexican nationalism in her own way. Moreover, painting alongside Rivera helped her understand the concepts of Mexican muralism which captured social and political awareness but also showed the indigenous roots that have shaped Latin Americans and Mexicans.[43] At the time, it was rare for a woman to have such popularity and independence, but despite working in a heavily male dominated field, Lazo successfully managed to become a muralist.[43] While she was originally from Guatemala, Huerta began to grow fond of Mexico during her collaboration with Rivera despite originally being from Guatemala, ultimately showing the influence that the Mexican Revolution had through her artwork.

Considered one of the first female artists of the Mexican muralism movement,[44] she painted several murals, the most important one being located at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

Additional prominent artworks

[edit]- Diego Rivera, Creation, National Preparatory School, 1922

- Diego Rivera, History of Mexico, National Palace, 1929–35

- Diego Rivera, The Sleeping Earth, Chapingo Chapel, 1926-1928

- Diego Rivera, Fecund Earth, Chapingo Chapel, 1926-1928

- Diego Rivera, Underground Organization of the Agrarian Movement, Chapingo Chapel, 1926-1928

- Orozco, The Revolutionary Trinity, National Preparatory School, 1923-1924

- Orozco, The Rich People, National Preparatory School, 1924

- Orozco, The Trench, National Preparatory School, 1926

- Orozco, Catharsis, Palacio de Bellas Artes, 1934-1935

- Siqueiros & Renau, Portrait of the Bourgeoisie, Electrical Workers Union,1939-1940

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Mexican Muralism". Art History Teaching Resources. 2014-09-26. Retrieved 2021-11-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Kenny, John Eugene (2006). The Chicano Mural movement of the Southwest: Populist public art and Chicano political activism (PhD). University of New Orleans. OCLC 3253092.

- ^ "Plasmó Juan Cordero primer mural en México con temas filosóficos" [Juan Cordero plastered the first mural with philosophical themes in Mexico]. NOTIMEX (in Spanish). Mexico City. May 27, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The art of Ramón Contreras and the Mexican Muralists movement" (PDF). San Bernardino County Museum. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Mainero del Castillo, Luz Elena (2012). "El muralismo y la Revolución Mexicana" [Muralism and the Mexican Revolution] (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Populist art and the Mexican mural renaissance". Hispanic Heritage in the Americas -Latin American art. Britannica. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ^ a b Burton, Tony (March 14, 2008). "Dr. Atl and the revolution in Mexico's art". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ^ Meade, Teresa A. (2016) History of Modern Latin America: 1800 to the Present. Wiley-Blackwell, p. 188.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Pomade, Rita (May 5, 2007). "Mexican muralists: the big three - Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ^ a b c Anreus, Alejandro. Folgarait, Leonard. Greeley, Robin Adèle (2012). Mexican muralism : a critical history. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27161-6. OCLC 815064840.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Folgariat, Leonard (1998). Mural painting and Social Revolution in Mexico 1920-1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–46. ISBN 0-521-58147-8.

- ^ a b c d Luis-Martín., Lozano (2007). Diego Rivera : the complete murals. Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-4943-9. OCLC 86168739.

- ^ Meade, Teresa A. (2016). History of Modern Latin America: 1800 to the Present. Wiley-Blackwell, p. 15, 188.

- ^ a b c Coffey, Mary (2002). "Muralism and The People: Culture, Popular Citizenship, and Government in Post-Revolutionary Mexico". The Communication Review. 5: 7–38. doi:10.1080/10714420212350. S2CID 144724797.

- ^ a b c Leonard, Folgarait (1998). Mural Painting and Social Revolution in Mexico, 1920-1940: Art of the New Order. Cambridge University Press. p. 7.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Bruce (2003). Mexican Murals in Times of Crisis. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press. p. 58.

- ^ "8. The Maya Tradition: Sculpture and Painting", The Art and Architecture of Ancient America: The Mexican, Maya and Andean Peoples, Yale University Press, 1992, doi:10.37862/aaeportal.00123.013, ISBN 9780300053258, retrieved 2021-12-08

- ^ James Oles (January 12, 2000). "Testigo de los anos 30" [Witness to the 1930s]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Escuela Mexicana de Pintura y Escultura" [Mexican School of Painting and Sculpting] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Artes e Historia magazine. Archived from the original on December 12, 2000. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ^ a b Campbell, Bruce (2003). Mexican Murals in Times of Crisis. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-8165-2239-1.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Bruce (2003). Mexican Murals in Times of Crisis. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 71. ISBN 0-8165-2239-1.

- ^ Meade, Teresa A. (2016). History of Modern Latin America: 1800 to the Present. Wiley-Blackwell, p. 188.

- ^ Barnet-Sanchez, Holly (2001). "Mexican Mural Movement." In Carrasco, David L (ed). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures: he Civilizations of Mexico and Central America vol. 2: New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 300 - 302.

- ^ a b Cambell, Bruce (2003). Mexican Murals in Times of Crisis. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-8165-2239-1.

- ^ a b c d Folgarait, Leonard (2017-07-27). "The Mexican Muralists and Frida Kahlo". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.464. ISBN 9780199366439. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ a b Jesus, Carlos Suarez De (2007-07-05). "Mexican Master". Miami New Times. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ "Rufino Tamayo | Mexican artist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ "Tamayo: A Modern Icon Reinterpreted | Santa Barbara Museum of Art". www.sbma.net. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ "When Diego Rivera turned propaganda into art | Art | Agenda". Phaidon. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- ^ "Jose Clemente Orozco - The trench". en.wahooart.com. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ "Art, Identity, and Culture » Siqueros – Portrait Essay". Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ Richardson, William (1987). "The Dilemmas of a Communist Artist: Diego Rivera in Moscow, 1927-1928". Mexican Studies. 3 (1): 49–69. doi:10.2307/4617031. JSTOR 4617031.

- ^ Cambell, Bruce (2003). Mexican Murals in Times of Crisis. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 48. ISBN 0-8165-2239-1.

- ^ a b Hubbard, Kathy (September 2010). "A CROSS-CULTURAL COLLABORATION: Using Visual Culture for the Creation of a Socially Relevant Mural in Mexico". Art Education. 63 (5): 68–75. doi:10.1080/00043125.2010.11519091. S2CID 151280989.

- ^ Del Barco, Mandalit. Revolutionary Mural To Return To L.A. After 80 Years. npr. October 26, 2010. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ Knight, Christopher. Art Review: 'America Tropical' transformed once more. Los Angeles Times. October 8, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ David Kunzle, The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua, 1979-1992. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1995.

- ^ a b c d "The Great Women of Muralism in Mexico". www.mexicanist.com. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- ^ "Aurora Reyes fue la primera muralista mexicana". Vanguardia MX (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Crítica, La (2018-08-03). "¿Dónde están los murales de las pintoras mexicanas?". La Crítica (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ "Los 'muros de una saltillense". 2015-06-24. Archived from the original on 2015-06-24. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ "Diego Rivera, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park – Smarthistory". smarthistory.org. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ a b Steinhauer, Jillian (2019-12-18). "Rina Lazo, Muralist Who Worked With Diego Rivera, Dies at 96". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ "Murió Fanny Rabel, pionera del muralismo en México". 30 November 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Anreus, Robin Adèle Greeley, and Leonard Folgarait, eds. Mexican Muralism: A Critical History. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 2012.

- Barnet-Sanchez, Holly. "Mexican Mural Movement." The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures vol 2. New York : Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Campbell, Bruce. Mexican Murals in Times of Crisis. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 2003.

- Carter, Warren (15 July 2014). "Painting the Revolution: State, Politics and Ideology in Mexican Muralism" (PDF). Third Text. 28: 282–291. doi:10.1080/09528822.2014.900922. S2CID 155480460.

- Charlot, Jean. The Mexican Mural Renaissance, 1920-1925. New Haven: Yale University Press 1967.

- Coffey, Mary. How a Revolutionary Art Became Official Culture: Murals, Museums, and the Mexican State. Durham: Duke University Press 2012.

- Elliott, Ingrid. "Visual Arts: 1910-37, The Revolutionary Tradition." Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 1576-1584.

- Folgarait, Leonard. Mural Painting and Social Revolution in Mexico, 1920-1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1998.

- Folgarait, Leonard (27 July 2017). "The Mexican Muralists and Frida Kahlo". The Mexican Muralists and Frida Kahlo. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.464. ISBN 9780199366439.

- Good, Carl and John V. Waldron, eds. The Effects of the Nation: Mexican Art in an Age of Globalization. Philadelphia: Temple University Press 2001.

- Hurlburt, Laurance P. The Mexican Muralists in the United States. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press

- Indych-López, Anna. Muralism Without Walls: Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros in the United States, 1927-1940. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 2009.

- Jaimes, Héctor. Filosofía del muralismo mexicano: Orozco, Rivera y Siqueiros. México: Plaza y Valdés, 2012.

- Jolly, Jennifer "Art of the Collective: David Alfaro Siqueiros, Josep Renau, and Their Collaboration at the Mexican Electricians' Syndicate," Oxford Art Journal 31.1 (2008): 129–151; and Laurance Hurlburt, The Mexican Muralists in the United States. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1989.

- Lear, John. Picturing the Proletariat: Artists and Labor in Revolutionary Mexico, 1908-1940. Austin: University of Texas Press 2017. ISBN 9781477311509

- Lee, Anthony. Painting on the Left: Diego Rivera, Radical Politics, and San Francisco's Public Murals. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1999.

- Lopez Orozco, Leticia (May 2014). "The Revolution, Vanguard Artists and Mural Painting". Third Text. 28 (3): 256–268. doi:10.1080/09528822.2014.935566. S2CID 219626971.

- Rivera, Diego, and Wolfe, Bertram David. Portrait of Mexico: Paintings by Diego Rivera and text by Bertram D. Wolfe. New York: Covici, Friede, 1937.

- Rodríguez, Antonio. A History of Mexican Mural Painting. London: Thames & Hudson 1969.

- Rochfort, Desmond.Mexican Muralists. San Francisco: Chronicle Books 1993.

- Wechsler, James. "Beyond the Border: The Mexican Mural Movement's Reception in Soviet Russia and the United States." in Luis Martín Lozano, ed. Mexican Modern Art: 1900-1930. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada 1999.

External links

[edit]Murals in Mexico.

- mural.ch Largest public accessible database on modern muralism with thousands of works, authors, and literature entries

- The Art that made Mexico on BBC Four

- Collection: "Era of the Mexican Revolution and the Mexican Muralist Movement" from the University of Michigan Museum of Art

- Exhibition: "Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art" at the Whitney Museum of American Art

- Mexican Muralism at the Museum of Modern Art

- Mexican Mural History Project at the Heritage Society at Sam Houston Park

- Mexican Muralism: Los Tres Grandes—David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco

- The History of Mexico: Diego Rivera's Murals at the National Palace