Metacomet Ridge

| Metacomet Ridge | |

|---|---|

Traprock cliffs on Chauncey Peak, Connecticut | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Toby |

| Elevation | 1,269 ft (387 m) |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 100 mi (160 km) north–south |

| Geography | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| States | Connecticut and Massachusetts |

| Geology | |

| Formed by | Fault blocking |

| Rock age(s) | Triassic and Jurassic |

| Rock type(s) | Igneous and sedimentary |

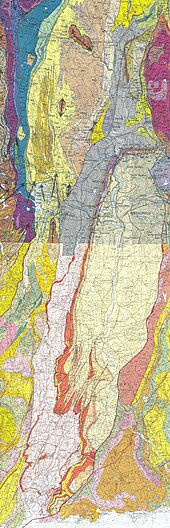

The Metacomet Ridge, Metacomet Ridge Mountains, or Metacomet Range of southern New England is a narrow and steep fault-block mountain ridge known for its extensive cliff faces, scenic vistas, microclimate ecosystems, and rare or endangered plants. The ridge is an important recreation resource located within 10 miles (16 km) of more than 1.5 million people, offering four long-distance hiking trails and over a dozen parks and recreation areas, including several historic sites. It has been the focus of ongoing conservation efforts because of its natural, historic, and recreational value, involving municipal, state, and national agencies and nearly two dozen non-profit organizations.[1][2]

The Metacomet Ridge extends from Branford, Connecticut, on Long Island Sound, through the Connecticut River Valley region of Massachusetts, to northern Franklin County, Massachusetts, 2 miles (3 km) short of the Vermont and New Hampshire borders for a distance of 100 miles (160 km). It is geologically distinct from the nearby Appalachian Mountains and surrounding uplands, and is composed of volcanic basalt (also known as trap rock) and sedimentary rock in faulted and tilted layers many hundreds of feet thick. In most cases, the basalt layers are dominant, prevalent, and exposed. The ridge rises dramatically from much lower valley elevations, although only 1,200 feet (370 m) above sea level at its highest, with an average summit elevation of 725 feet (221 m).[1][3]

Geographic definitions

[edit]Visually, the Metacomet Ridge exists as one continuous landscape feature from Long Island Sound at Branford, Connecticut, to the end of the Mount Holyoke Range in Belchertown, Massachusetts, a distance of 71 miles (114 km), broken only by the river gorges of the Farmington River in northern Connecticut and the Westfield and Connecticut Rivers in Massachusetts.[1] It was first identified in 1985 as a single geologic feature consisting of trap rock by the State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut.[4] A 2004 report conducted for the National Park Service extends that definition to include the entire traprock ridge from Long Island Sound to the Pocumtuck Range in Greenfield, Massachusetts.[1] Further complicating the matter is the fact that traprock only accounts for the highest surface layers of rock strata on the southern three–fourths of the range; an underlying geology of related sedimentary rock is also a part of the structure of the ridge; in north central Massachusetts it becomes the dominant strata and extends the range geologically from the Holyoke Range another 35 miles (56 km) through Greenfield to nearly the Vermont border.[5][6]

Nomenclature

[edit]

Until January 2008, the United States Board on Geographic Names (USBGN) did not recognize Metacomet Ridge, Traprock Ridge or any other name, although several sub-ranges were identified.[7][8] Geologists usually refer to the overall range generically as "the traprock ridge" or "the traprock mountains" or refer to it with regard to its prehistoric geologic significance in technical terms.[5] The Sierra Club has referred to the entire range in Connecticut as "The Traprock Ridge".[9] The name Metacomet Ridge was first applied in 1985 in a book published by the Connecticut State Geological Survey, adopting the name from the existing Metacomet Trail along a large portion of the range in central Connecticut.[4]

The name "Metacomet" or "Metacom" is borrowed from the 17th century sachem of the Wampanoag Tribe of southern New England who led his people during King Philip's War in the mid–17th century. Metacomet was also known as King Philip by early New England colonists. A number of features associated with the Metacomet Ridge are named after the sachem, including the Metacomet Trail, the Metacomet-Monadnock Trail, King Philip's Cave, King Philip Mountain, and Sachem Head. According to legend, Metacomet orchestrated the burning of Simsbury, Connecticut, and watched the conflagration from Talcott Mountain near the cave now named after him.[10][11][12] The names Metacomet and King Philip have been applied to at least sixteen landscape features and over seventy-five businesses, schools, and civic organizations throughout southern New England.[13][14]

Geography

[edit]

Beginning at Long Island Sound, the Metacomet Ridge commences as two parallel ridges with related sub-ridges and outcrops in between; the latter include the high butte–like cliffs of East Rock and the isolated peak of Peter's Rock. The western ridgeline of the Metacomet Ridge begins in New Haven, Connecticut, as West Rock Ridge and continues as Sleeping Giant, Mount Sanford, Peck Mountain, and Prospect Ridge, for a distance of 16 miles (26 km) before diminishing into a series of low profile outcrops just short of Southington, Connecticut, 2.75 miles (4.4 km) west of the Hanging Hills in Meriden.[3][15]

To the east, beginning on the rocky prominence of Beacon Hill, 130 feet (40 m),[16] in Branford, Connecticut, overlooking the East Haven River estuary, the Metacomet Ridge continues as a traprock ridge 60 miles (97 km) north to Mount Tom in Holyoke, Massachusetts; it then breaks east across the Connecticut River to form the Holyoke Range, which continues for 10 miles (16 km) before terminating in Belchertown, Massachusetts. Several scattered parallel ridges flank it; the most prominent of these are the hills of Rocky Hill, Connecticut, and the Barn Door Hills of Granby, Connecticut.[3][15]

North of Mount Tom and the Holyoke Range, the apparent crest of the Metacomet Ridge is broken by a discontinuity in the once dominant traprock strata. Underlying sedimentary layers remain but lack the same profile. Between the Holyoke Range and the Pocumtuck Ridge, a stretch of 9 miles (14 km), the Metacomet Ridge exists only as a series of mostly nondescript rises set among flat plains of sedimentary bedrock. Mount Warner, 512 feet (156 m), in Hadley, Massachusetts, the only significant peak in the area, is a geologically unrelated metamorphic rock landform that extends west into the sedimentary strata.[17]

The Metacomet Ridge picks up elevation again with the Pocumtuck Ridge, beginning on Sugarloaf Mountain and the parallel massif of Mount Toby, 1,269 feet (387 m),[16] the high point of the Metacomet Ridge geography. Both Sugarloaf Mountain and Mount Toby are composed of erosion-resistant sedimentary rock. North of Mount Sugarloaf, the Pocumtuck Ridge continues as alternating sedimentary and traprock dominated strata to Greenfield, Massachusetts. From Greenfield north to Northfield, Massachusetts 2 miles (3 km) short of the Vermont–New Hampshire–Massachusetts tri-border, the profile of the Metacomet Ridge diminishes into a series of nondescript hills and low, wooded mountain peaks composed of sedimentary rock with dwindling traprock outcrops.[1][5][17]

In Connecticut, the high point of the Metacomet Ridge is West Peak of the Hanging Hills at 1,024 feet (312 m); in Massachusetts, the highest traprock peak is Mount Tom, 1,202 feet (366 m), although Mount Toby, made of sedimentary rock, is higher.[16] Visually, the Metacomet Ridge is narrowest at Provin Mountain and East Mountain in Massachusetts where it is less than 0.5 miles (1 km) wide; it is widest at Totoket Mountain, over 4 miles (6 km). However, low parallel hills and related strata along much of the range often make the actual geologic breadth of the Metacomet Ridge wider than the more noticeable ridgeline crests, up to 10 miles (16 km) across in some areas. Significant river drainages of the Metacomet Ridge include the Connecticut River and tributaries (Falls River, Deerfield River, Westfield River, Farmington River, Coginchaug River); and, in southern Connecticut, the Quinnipiac River.[3]

The Metacomet Ridge is surrounded by rural wooded, agricultural, and suburban landscapes, and is no more than 6 miles (10 km) from a number of urban hubs such as New Haven, Meriden, New Britain, Hartford, and Springfield. Small city centers abutting the ridge include Greenfield, Northampton, Amherst, Holyoke, West Hartford, Farmington, Wallingford, and Hamden.[3]

Geology

[edit]

The Metacomet Ridge is the result of continental rifting processes that took place 200 million years ago during the Triassic and Jurassic periods. The basalt (also called traprock) crest of the Metacomet Ridge is the product of a series of massive lava flows hundreds of feet thick that welled up in faults created by the rifting apart of the North American continent from Eurasia and Africa. Essentially, the area now occupied by the Metacomet Ridge is a prehistoric rift valley which was once a branch of (or a parallel of) the major rift to the east that became the Atlantic Ocean.[6]

Basalt is a dark colored extrusive volcanic rock. The weathering of iron-bearing minerals within it results in a rusty brown color when exposed to air and water, lending it a distinct reddish or purple–red hue. Basalt frequently breaks into octagonal and pentagonal columns, creating a unique "postpile" appearance. Extensive slopes made of fractured basalt talus are visible at the base of many of the cliffs along the Metacomet Ridge.[6]

The basalt floods of lava that now form much of the Metacomet Ridge took place over a span of 20 million years. Erosion and deposition occurring between the eruptions deposited layers of sediment between the lava flows which eventually lithified into sedimentary rock layers within the basalt. The resulting "layer cake" of basalt and sedimentary rock eventually faulted and tilted upward (see fault-block). Subsequent erosion wore away many of the weaker sedimentary layers at a faster rate than the basalt layers, leaving the abruptly tilted edges of the basalt sheets exposed, creating the distinct linear ridge and dramatic cliff faces visible today on the western and northern sides of the ridge.[6] Evidence of this layer-cake structure is visible on Mount Norwottuck of the Holyoke Range in Massachusetts. The summit of Norwottuck is made of basalt; directly beneath the summit are the Horse Caves, a deep overhang where the weaker sedimentary layer has worn away at a more rapid rate than the basalt layer above it. Mount Sugarloaf, Pocumtuck Ridge, and Mount Toby, also in Massachusetts, together present a larger "layer cake" example. The bottom layer is composed of arkose sandstone, visible on Mount Sugarloaf. The middle layer is composed of volcanic traprock, most visible on the Pocumtuck Ridge. The top layer is composed of a sedimentary conglomerate known as Mount Toby Conglomerate. Faulting and earthquakes during the period of continental rifting tilted the layers diagonally; subsequent erosion and glacial activity exposed the tilted layers of sandstone, basalt, and conglomerate visible today as three distinct mountain masses. Although Mount Toby and Mount Sugarloaf are not composed of traprock, they are part of the Metacomet Ridge by virtue of their origin via the same rifting and uplift processes.[5]

Of all the summits that make up the Metacomet Ridge, West Rock, in New Haven, Connecticut, bears special mention because it was not formed by the volcanic flooding that created most of the traprock ridges. Rather, it is the remains of an enormous volcanic dike through which the basalt lava floods found access to the surface.[6]

While the traprock cliffs remain the most obvious evidence of the prehistoric geologic processes of the Metacomet Ridge, the sedimentary rock of the ridge and surrounding terrain has produced equally significant evidence of prehistoric life in the form of Triassic and Jurassic fossils; in particular, dinosaur tracks. At a state park in Rocky Hill, Connecticut, more than 2,000 well preserved early Jurassic prints have been excavated.[18] Other sites in Holyoke and Greenfield have likewise produced significant finds.[6][19]

Ecosystem

[edit]

The Metacomet Ridge hosts a combination of microclimates unusual to the region. Dry, hot upper ridges support oak savannas, often dominated by chestnut oak and a variety of understory grasses and ferns. Eastern red-cedar, a dry-loving species, clings to the barren edges of cliffs. Backslope plant communities tend to be similar to the adjacent upland plateaus and nearby Appalachians, containing species common to the northern hardwood and oak-hickory forest ecosystem types. Eastern hemlock crowds narrow ravines, blocking sunlight and creating damp, cooler growing conditions with associated cooler climate plant species. Talus slopes are especially rich in nutrients and support a number of calcium-loving plants uncommon in the region. Miles of high cliffs make ideal raptor habitat, and the Metacomet Ridge is a seasonal raptor migration corridor.

Because the topography of the ridge offers such varied terrain, many species reach the northern or southern limit of their range on the Metacomet Ridge; others are considered rare nationally or globally. Examples of rare species that live on the ridge include the prickly pear cactus, peregrine falcon, northern copperhead, showy lady's slipper, yellow corydalis, ram's–head lady's slipper, basil mountain mint, and devil's bit lily.[1][20]

The Metacomet Ridge is also an important aquifer.[1] It provides municipalities and towns with public drinking water; reservoirs are located on Talcott Mountain, Totoket Mountain, Saltonstall Mountain, Bradley Mountain, Ragged Mountain, and the Hanging Hills in Connecticut. Reservoirs that supply metropolitan Springfield, Massachusetts, are located on Provin Mountain and East Mountain.[10][12]

History

[edit]Pre-colonial era

[edit]

Native Americans occupied the river valleys surrounding the Metacomet Ridge for at least 10,000 years. Major tribal groups active in the area included the Quinnipiac, Niantic, Pequot, Pocomtuc, and Mohegan. Traprock was used to make tools and arrowheads. Natives hunted game, gathered plants and fruits, and fished in local bodies of water around the Metacomet Ridge. Tracts of woodland in the river bottoms surrounding the ridges were sometimes burned to facilitate the cultivation of crops such as corn, squash, tobacco, and beans.[1][21]

Natives incorporated the natural features of the ridgeline and surrounding geography into their spiritual belief systems. Many Native American stories were in turn incorporated into regional colonial folklore. The giant stone spirit Hobbomock (or Hobomock), a prominent figure in many stories, was credited with diverting the course of the Connecticut River where it suddenly swings east in Middletown, Connecticut, after several hundred miles of running due south. Hobbomuck is also credited with slaying a giant human-eating beaver who lived in a great lake that existed in the Connecticut River Valley of Massachusetts. According to native beliefs as retold by European settlers, the corpse of the beaver remains visible as the Pocumtuck Ridge portion of the Metacomet Ridge. Later, after Hobbomuck diverted the course of the Connecticut River, he was punished to sleep forever as the prominent man-like form of the Sleeping Giant, part of the Metacomet Ridge in southern Connecticut. There seems to be an element of scientific truth in some of these tales. For instance, the great lake that the giant beaver was said to have inhabited may very well have been the post-glacial Lake Hitchcock, extant 10,000 years ago; the giant beaver may have been an actual prehistoric species of bear–sized beaver, Castoroides ohioensis, that lived at that time.[22][23][24] Many features of the Metacomet Ridge region still bear names with Native American origins: Besek, Pistapaug, Coginchaug, Mattabesett, Metacomet, Totoket, Norwottuck, Hockanum, Nonotuck, Pocumtuck, and others.[1][11][12]

Colonization, agricultural transformation, and industrialization

[edit]

Europeans began settling the river valleys around the Metacomet Ridge in the mid–17th century. Forests were cut down or burned to make room for agriculture, resulting in the near complete denuding of the once contiguous forests of southern New England by the 19th century. Steep terrain like the Metacomet Ridge, while not suitable for planting crops, was widely harvested of timber as a result of the expanding charcoal industry that boomed before the mining of coal from the mid–Appalachian regions replaced it as a source of fuel. In other cases, ridgetop forests burned when lower elevation land was set afire, and some uplands were used for pasturing.[1][21] Traprock was harvested from talus slopes of the Metacomet Ridge to build house foundations;[1] copper ore was discovered at the base of Peak Mountain in northern Connecticut and was mined by prisoners incarcerated at Old Newgate Prison located there.[25]

With the advent of industrialization in the 19th century, riverways beneath the Metacomet Ridge were dammed to provide power as the labor force expanded in nearby cities and towns. Logging to provide additional fuel for mills further denuded the ridges. Traprock and sandstone were quarried from the ridge for paving stones and architectural brownstone, either used locally or shipped via rail, barge, and boat.[1][21][26]

Transcendentalism

[edit]

Increased urbanization and industrialization in Europe and North America resulted in an opposing aesthetic transcendentalist movement characterized in New England by the art of Thomas Cole, Frederic Edwin Church, and other Hudson River School painters, the work of landscape architects such as Frederick Law Olmsted, and the writings of philosophers such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. As was true of other scenic areas of New England, the philosophical, artistic, and environmental movement of transcendentalism transformed the Metacomet Ridge from a commercial resource to a recreational resource.[1] Hotels, parks, and summer estates were built on the mountains from the mid-1880s to the early 20th century. Notable structures included summit hotels and inns on Mount Holyoke, Mount Tom, Sugarloaf Mountain, and Mount Nonotuck.[27][28] Parks and park structures such as Poet's Seat in Greenfield, Massachusetts, and Hubbard Park (designed with the help of Frederick Law Olmsted) of the Hanging Hills of Meriden, Connecticut, were intended as respites from the urban areas they closely abutted.[29][30] Estates such as Hill-Stead and Heublein Tower were built as mountain home retreats by local industrialists and commercial investors.[31][32] Although public attention gradually shifted to more remote and less developed destinations with the advent of modern transportation and the westward expansion of the United States, the physical, cultural, and historic legacy of that early recreational interest in the Metacomet Ridge still supports modern conservation efforts. Estates became museums; old hotels and the lands they occupied, frequently subject to damaging fires, became state and municipal parkland through philanthropic donation, purchase, or confiscation for unpaid taxes. Nostalgia among former guests of hotels and estates contributed to the aesthetic of conservation.[1][29][12][28][31]

Trailbuilding

[edit]Interest in mountains as places to build recreational footpaths took root in New England with organizations such as the Appalachian Mountain Club, the Green Mountain Club, the Appalachian Trail Conference, and the Connecticut Forest and Park Association.[33][34][35] Following the pioneering effort of the Green Mountain Club in the inauguration of Vermont's Long Trail in 1918,[36] the Connecticut Forest and Park Association, spearheaded by Edgar Laing Heermance, created the 23 miles (37 km) Quinnipiac Trail on the Metacomet Ridge in southern Connecticut in 1928 and soon followed it up with the 51 miles (82 km) Metacomet Trail along the Metacomet Ridge in central and northern Connecticut. More than 700 miles (1,100 km) of "blue blaze trails" in Connecticut were completed by the association by the end of the 20th century.[35] While the focus of the Appalachian Mountain Club was geared primarily toward the White Mountains of New Hampshire in its early years, as club membership broadened, so did interest in the areas closer to club members' homes.[33][34][37] In the late 1950s, the 110 miles (180 km) Metacomet-Monadnock Trail was laid out by the Berkshire Chapter of the Appalachian Mountain Club under leadership of Professor Walter M. Banfield of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The trail follows the Metacomet Ridge for the first one–third of its length.[10] Overall, trailbuilding had a pro-active effect on conservation awareness by thrusting portions of the Metacomet Ridge into the public consciousness.[1]

Suburbanization and land conservation

[edit]Although the Metacomet Ridge has abutted significant urban areas for nearly two hundred years, because of its rugged, steep, and rocky terrain, the ridge was long considered an undesirable place to build a home except for those wealthy enough to afford such a luxury. However, suburbanization through urban exodus and automobile culture, and modern construction techniques and equipment have created a demand for homes on and around the once undeveloped Metacomet Ridge and its surrounding exurban communities.[1] As of 2007, the metropolitan areas bordering the range—New Haven, Meriden, New Britain, Hartford, Springfield and Greenfield—had a combined population of more than 2.5 million people.[2] Populations in exurban towns around the range in Connecticut have increased 7.6 percent between the mid-1990s to 2000, and building permits increased 26 percent in the same period. Considered an attractive place to build homes because of its views and proximity to urban centers and highways, the Metacomet Ridge has become a target for both developers and advocates of land conservation. Quarrying, supported by the increased need for stone in local and regional construction projects, has been especially damaging to the ecosystem, public access, and visual landscape of the ridge.[1] At the same time, the boom in interest in outdoor recreation in the latter 20th century has made the Metacomet Ridge an attractive "active leisure" resource. In response to public interest in the ridge and its surrounding landscapes, more than twenty local non-profit organizations have become involved in conservation efforts on and around the ridge and surrounding region. Most of these organizations came into being between 1970 and 2000, and nearly all of them have evidenced a marked increase in conservation activity since 1990.[38] Several international and national organizations have also become interested in the Metacomet Ridge, including The Nature Conservancy, the Sierra Club, and the Trust for Public Land.[9][39][40]

Recreation

[edit]

Steepness, long cliff–top views, and proximity to urban areas make the Metacomet Ridge a significant regional outdoor recreation resource.[1] The ridge is traversed by more than 200 miles (320 km) of long-distance and shorter hiking trails. Noteworthy trails in Connecticut include the 51-mile (82 km) Metacomet Trail, the 50-mile (80 km) Mattabesett Trail, the 23-mile (37 km) Quinnipiac Trail, and the 6-mile (10 km) Regicides Trail. Massachusetts trails include the 110-mile (177 km) Metacomet-Monadnock Trail, the 47-mile (76 km) Robert Frost Trail, and the 15-mile (24 km) Pocumtuck Ridge Trail. Site–specific activities enjoyed on the ridge include rock climbing, bouldering, fishing, boating, hunting, swimming, backcountry skiing, cross-country skiing, trail running, bicycling, and mountain biking. Trails on the ridge are open to snowshoeing, birdwatching and picnicking as well. The Metacomet Ridge hosts more than a dozen state parks, reservations, and municipal parks, and more than three dozen nature preserves and conservation properties. Seasonal automobile roads with scenic vistas are located at Poet's Seat Park, Mount Sugarloaf State Reservation, J.A. Skinner State Park, the Mount Tom State Reservation, Hubbard Park, and West Rock Ridge State Park; these roads are also used for bicycling and cross–country skiing. Camping and campfires are discouraged on most of the Metacomet Ridge, especially in Connecticut. Museums, historic sites, interpretive centers, and other attractions can be found on or near the Metacomet Ridge; some offer outdoor concerts, celebrations, and festivals.[10][12][41][42]

Conservation

[edit]

Because of its narrowness, proximity to urban areas, and fragile ecosystems, the Metacomet Ridge is most endangered by encroaching suburban sprawl. Quarry operations, also a threat, have obliterated several square miles of traprock ridgeline in both Massachusetts and Connecticut. Ridges and mountains affected include Trimountain, Bradley Mountain, Totoket Mountain, Chauncey Peak, Rattlesnake Mountain, East Mountain, Pocumtuck Ridge, and the former Round Mountain of the Holyoke Range.[1][3][43] The gigantic man-like profile of the Sleeping Giant, a traprock massif visible for more than 30 miles (50 km) in south central Connecticut, bears quarrying scars on its "head". Mining there was halted by the efforts of local citizens and the Sleeping Giant Park Association.[12]

Development and quarrying threats to the Metacomet Ridge have resulted in public open space acquisition efforts through collective purchasing and fundraising, active solicitation of land donations, securing of conservation easements, protective and restrictive legislation agreements limiting development, and, in a few cases, land taking by eminent domain.[1][15][28][44] Recent conservation milestones include the acquisition of a defunct ski area on Mount Tom,[44] the purchase of the ledges and summits of Ragged Mountain through the efforts of a local rock climbing club and the Nature Conservancy,[45] and the inclusion of the ridgeline from North Branford, Connecticut, to Belchertown, Massachusetts, in a study by the National Park Service for a new National Scenic Trail now tentatively called the New England National Scenic Trail.[46] Metacomet Ridge Conservation Compact, a Connecticut focus on ridgeline protection was initiated with the creation of the Metacomet Ridge Conservation Compact. The compact was ratified on Earth Day, April 22, 1998. The Compact serves as a guide for local land use decision-makers when discussing land use issues in Metacomet or Trap Rock ridge-line areas within the state. Ultimately signed by eighteen towns out of the nineteen ridge-line communities, this agreement committed local conservation commissions to strive to protect these ridges. The 18 towns whose Conservation Commissions signed the pact are; Avon, Berlin, Bloomfield, Branford, Durham, East Granby, East Haven, Farmington, Guilford, Meriden, Middlefield, North Branford, Plainville, Simsbury, Suffield, Wallingford, West Hartford and West Haven.

See also

[edit]- List of Metacomet Ridge summits

- List of subranges of the Appalachian Mountains

- Traprock mountains in other parts of the world

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Metacomet-Mattabesett Trail Natural Resource Assessment" (PDF). Farnsworth, Elizabeth J. (2004). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ a b United States Census Bureau. Data retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f DeLorme Topo 6.0 (2006). Mapping software. Yarmouth, Maine: DeLorme.

- ^ a b Bell, Michael (1985). The Face of Connecticut: People, Geology, and the Land. Hartford, CT: State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut.

- ^ a b c d Olsen, Paul E., McDonald, Nicholas G., Huber, Phillip, Cornet, Bruce (October 9–10-11, 1992). "Stratigraphy and Paleoecology of the Deerfield Rift Basin (Triassic-Jurassic, Newark Supergroup), Massachusetts." Guidebook for Field Trips in the Connecticut Valley Region of Massachusetts and Adjacent States vol. 2, pp. 488–535. 84th annual meeting, New England Intercollegiate Geological Conference, Amherst, Massachusetts: The Five Colleges. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Raymo, Chet and Raymo, Maureen E. (1989). Written in Stone: A Geologic History of the Northeastern United States. Chester, Connecticut: Globe Pequot.

- ^ United States Board on Geographic Names domestic names search. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ United States Board on Geographic Names domestic names search. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ a b "SPARE America's Wildlands". Sierra Club. Archived from the original on 19 July 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d The Metacomet-Monadnock Trail Guide, 9th edition (1999). Amherst, Massachusetts: Appalachian Mountain Club.

- ^ a b Massachusetts Trail Guide, 8th edition. (2004). Boston: Appalachian Mountain Club.

- ^ a b c d e f Connecticut Walk Book East: The Trail Guide to the Blue Blazed Hiking Trails of Eastern Connecticut (2005) 19th edition. Rockfall, Connecticut: Connecticut Forest and Park Association.

- ^ United States Board on Geographic Names domestic names search. Searches conducted: "Metacomet," "Metacom," "King Phillip," and "King Philip." Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ WhitePages.com business search. Archived 2008-12-11 at the Wayback Machine Searches conducted: "Metacomet," "Metacom," "King Phillip," and "King Philip." Retrieved January 24, 2007

- ^ a b c "An Act Concerning a Model River Protection Ordinance and Protection of Ridgelines. Substitute Bill No. 5528" (PDF). Connecticut General Assembly. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c Estimated and actual elevations from United States Geological Survey 1:25000 and 1:24000 scale 7.5 minute series topographic maps obtained via Topozone.com. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ^ a b Zen, E-an, Goldsmith, Richard, Ratcliffe, N.M., Robinson, Peter, Stanley, R.S., Hatch, N.L., Shride, A.F., Weed, E.G.A., and Wones, D.R. (1983). Bedrock Geologic Map of Massachusetts. Washington: United States Geological Survey.

- ^ Dinosaur State Park. Friends of Dinosaur State Park. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ "Dinosaur Footprints" The Trustees of Reservations. Retrieved December 23, 2007. Archived December 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mount Toby Ecosystem" (PDF). The Mount Toby Partnership. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c Cronin, William (2003). Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. New York: Hill and Wang.

- ^ Field, Phinehas (1870–79). "Stories, anecdotes, and legends, collected and written down by Deacon Phinehas Field." History and Proceedings of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Deerfield, Massachusetts. 1:59.

- ^ Rittenour, Tammie Marie. "Native American Legend of the Giant Beaver." Archived 2007-12-09 at the Wayback Machine University of Massachusetts Amherst Department of Biology and the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Sleeping Giant" Archived 2015-05-11 at the Wayback Machine. Sleeping Giant Park Association. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ^ Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism[usurped]. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ^ Bass, Sharon (March 26, 1989). "The View From: Branford; Trolley Rides in the Cause of Open Space." The New York Times.

- ^ Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c Strycharz, Robb (1996–2006). "Mount Holyoke Historical Timelines." Chronos Historical Services. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ^ a b "Hubbard Park" (PDF). North Haven, Connecticut: South Central Regional Council of Governments. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ City of Greenfield, Massachusetts. Retrieved December 23, 2007. Archived October 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ^ Hill-Stead Museum Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ a b Waterman, Laura and Guy (2003). Forest and Crag, A History of Hiking, Trail Blazing, 2nd edition. Boston: Appalachian Mountain Club Books.

- ^ a b Lombardo, Michael S. (February 1, 2008). "Freshman Year Success via Outdoor Orientation Programs: A Brief History." newfoundations.com.

- ^ a b Connecticut Forest and Park Association. Retrieved December 23, 2007. Archived September 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Green Mountain Club. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ^ "AMC History." Archived 2007-12-30 at the Wayback Machine Appalachian Mountain Club. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ Regional examples include: Bethany Land Trust, Branford Land Trust, Berlin Land Trust Archived 2007-12-13 at the Wayback Machine, Simsbury Land Trust, Suffield Land Conservancy Archived 2007-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, The Trustees of Reservations,

The Kestrel Trust, and the Deerfield Land Trust. Organization websites. Retrieved December 21, 2007. Other examples provided in Wikipedia articles about specific summits in the range. - ^ "Metacomet Ridge Open Space Preserved (CT)" The Trust for Public Land. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ "Higby Mountain Preserve" Archived 2015-05-28 at the Wayback Machine The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved December 24, 2007.

- ^ Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ^ Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved December 8, 2007.

- ^ Google Earth. Satellite images of specified mountains. Google, inc. Retrieved December 7, 2007.

- ^ a b "Mount Tom: Defining the Landscape of the Connecticut River Valley." The Trustees of Reservations. Retrieved November 28, 2007. "Mount Tom - the Trustees of Reservations". Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Ragged Mountain Foundation. Retrieved December 7, 2007. "Index :: Ragged Mountain Foundation :: Preserving Connecticut's High and Wild Places". Archived from the original on December 12, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Monadnock, Metacomet, Mattabesett National Scenic Trail Study". United States National Park Service. Retrieved November 4, 2007. Archived October 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- United States Congress New England National Scenic Trail Designation Act. Archived 2016-07-04 at the Wayback Machine

- National Park Service brochure for National Scenic Trail proposal.

- Natural resource assessment of the Metacomet Ridge

- Geology of the northern Metacomet Ridge region

- Traprock Wilderness Recovery Strategy

- Guide to the Robert Frost Trail

- Connecticut Forest and Park Association

- Appalachian Mountain Club Berkshire Chapter

- Government agencies

- Maps and additional relevant external links provided under articles relating to specific summits of the Metacomet Ridge.

- Metacomet Ridge

- Metacomet Ridge, Connecticut

- Metacomet Ridge, Massachusetts

- Geography of New Haven, Connecticut

- Geology of Connecticut

- Geology of Massachusetts

- Landforms of New Haven County, Connecticut

- Raptor migration sites

- Ridges of Connecticut

- Ridges of Massachusetts

- Volcanism of Massachusetts

- Climbing areas of the United States