The medium is the message

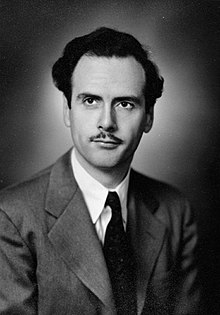

"The medium is the message" is a phrase coined by the Canadian communication theorist Marshall McLuhan and the name of the first chapter[1] in his Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, published in 1964.[2][3] McLuhan proposes that a communication medium itself, not the messages it carries, should be the primary focus of study.[4] The concept has been applied by others in discussions of technologies from television to the Internet.

McLuhan's theory

[edit]McLuhan uses the term "message" to signify content and character. The content of the medium is a message that can be easily grasped and the character of the medium is another message which can be easily overlooked. McLuhan says "Indeed, it is only too typical that the 'content' of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium". For McLuhan, it was the medium itself that shaped and controlled "the scale and form of human association and action".[5] Taking the movie as an example, he argued that the way this medium played with conceptions of speed and time transformed "the world of sequence and connections into the world of creative configuration and structure". Therefore, the message of the movie medium is this transition from "lineal connections" to "configurations."[6] Extending the argument for understanding the medium as the message itself, he proposed that the "content of any medium is always another medium"[7] – thus, speech is the content of writing, writing is the content of print, and print itself is the content of the telegraph.

McLuhan frequently punned on the word "message", changing it to "mass age", "mess age" and "massage". A later book, The Medium Is the Massage was originally to be titled The Medium is the Message, but McLuhan preferred the new title, which is said to have been a printing error.[8]

Concerning the title, McLuhan wrote:

The title "The Medium Is the Massage" is a teaser—a way of getting attention. There's a wonderful sign hanging in a Toronto junkyard which reads, 'Help Beautify Junkyards. Throw Something Lovely Away Today.' This is a very effective way of getting people to notice a lot of things. And so the title is intended to draw attention to the fact that a medium is not something neutral—it does something to people. It takes hold of them. It rubs them off, it massages them and bumps them around, chiropractically, as it were, and the general roughing up that any new society gets from a medium, especially a new medium, is what is intended in that title".[9]

McLuhan argues that a "message" is, "the change of scale or pace or pattern" that a new invention or innovation "introduces into human affairs".[10]

McLuhan understood "medium" as a medium of communication in the broadest sense. In Understanding Media he wrote: "The instance of the electric light may prove illuminating in this connection. The electric light is pure information. It is a medium without a message, as it were, unless it is used to spell out some verbal ad or name."[11] The light bulb is a clear demonstration of the concept of "the medium is the message": a light bulb does not have content in the way that a newspaper has articles or a television has programs, yet it is a medium that has a social effect; that is, a light bulb enables people to create spaces during nighttime that would otherwise be enveloped by darkness. He describes the light bulb as a medium without any content. McLuhan states that "a light bulb creates an environment by its mere presence".[7] Likewise, the message of a newscast about a heinous crime may be less about the individual news story itself (the content), and more about the change in public attitude towards crime that the newscast engenders by the fact that such crimes are in effect being brought into the home to watch over dinner.[12]

In Understanding Media, McLuhan describes the "content" of a medium as a juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind.[11] This means that people tend to focus on the obvious, which is the content, to provide us valuable information, but in the process, we largely miss the structural changes in our affairs that are introduced subtly, or over long periods of time. As society's values, norms, and ways of doing things change because of the technology, it is then we realize the social implications of the medium. These range from cultural or religious issues and historical precedents, through interplay with existing conditions, to the secondary or tertiary effects in a cascade of interactions that we are not aware of.[12]

On the subject of art history, McLuhan interpreted Cubism as announcing clearly that the medium is the message. For him, Cubist art required "instant sensory awareness of the whole" rather than perspective alone. In other words, with Cubism one could not ask what the artwork was about (content), but rather consider it in its entirety.[13] Many of the conceptions presented in this work are expansions, popularizations and applications of ideas initially conceived by Walter Benjamin and the dialog between his texts and other thinkers in the Frankfurt School in the 1930s and 1940s.[14]

Applications

[edit]Television

[edit]Neil Postman in his 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death worried that McLuhan's theory, if true, meant that television was uniquely destructive to the public conversation in America, with style trumping substance.[15]

Internet

[edit]Some modern journalists and academics have pointed to algorithms, social media and the internet as great examples of McLuhan's theory.[16][17][18][15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ McLuhan, Marshall (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. ISBN 81-14-67535-7.

- ^ Beynon-Davies, Paul (2011). "Communication: The medium is not the message". Significance. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 58–76. doi:10.1057/9780230295025_4. ISBN 978-1-349-32470-5.

- ^ Originally published in 1964 by Mentor, New York; reissued 1994, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts with an introduction by Lewis Lapham

- ^ Euchner, Jim (2016-08-26). "The Medium is the Message". Research-Technology Management. 59 (5). Informa UK Limited: 9–11. doi:10.1080/08956308.2016.1209068. ISSN 0895-6308.

- ^ McLuhan, Understanding Media, p. 9.

- ^ McLuhan, Understanding Media, p. 12.

- ^ a b McLuhan, Understanding Media, p. 8.

- ^ "Commonly Asked Questions about McLuhan – The Estate of Marshall McLuhan". marshallmcluhan.com. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ McLuhan, Marshall (1967-03-19). "McLuhan: Now The Medium Is The Massage". New York Times. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ^ Federman, Mark (July 23, 2004). "What is the Meaning of The Medium is the Message?". individual.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 2019-03-23.

- ^ a b McLuhan, Marshall (1964) Understanding Media, Routledge, London

- ^ a b Federman, M. (2004, July 23). "What is the Meaning of the Medium is the Message?". Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ McLuhan, Understanding Media, p. 13.

- ^ Russell, Catherine (2004). "New Media and Film History: Walter Benjamin and the Awakening of Cinema". Cinema Journal. 43 (3): 81–85. doi:10.1353/cj.2004.0024. ISSN 0009-7101. JSTOR 3661111.

- ^ a b Kang, Jay Caspian (2024-03-08). "Arguing Ourselves to Death". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2024-09-17.

- ^ "The algorithm will be the message". Nieman Lab. Retrieved 2024-09-17.

- ^ "Marshall McLuhan: The medium is the message". Al Jazeera. October 31, 2019. Retrieved 2024-09-17.

- ^ "Social media — why the medium is still the message". Deseret News. 2013-11-20. Retrieved 2024-09-17.

External links

[edit]- MediaTropes eJournal A scholarly journal, Vol. 1, Marshall McLuhan's "Medium is the Message": Information Literacy in a Multimedia Age

- Guardian Big Ideas podcast by Benjamen Walker