Medford, Oregon

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

Medford, Oregon | |

|---|---|

City and county seat | |

Clockwise, from top: aerial image of Medford, City Hall, the Medford Carnegie Library, Vogel Plaza, and Bear Creek Park | |

| Nickname: "Pear Blossom City" | |

| Motto: "Heart of the Rogue" | |

Location of Medford in Jackson County and Oregon | |

| Coordinates: 42°19′55″N 122°51′43″W / 42.33194°N 122.86194°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Jackson |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Randy Sparacino |

| • City manager | Brian Sjothun |

| Area | |

• City and county seat | 27.73 sq mi (71.81 km2) |

| • Land | 27.71 sq mi (71.78 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.03 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,382 ft (421 m) |

| Population | |

• City and county seat | 85,824 |

| • Rank | US: 425th |

| • Density | 3,096.66/sq mi (1,195.61/km2) |

| • Urban | 154,081 (US: 213th) |

| • Metro | 223,259 (US: 206th) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 97501, 97504 |

| Area codes | 541, 458 |

| FIPS code | 41-47000 |

| Website | medfordoregon.gov |

Medford is a city in and the county seat of Jackson County, Oregon, in the United States.[3] As of the 2020 United States Census on April 1, 2020, the city had a total population of 85,824, making it the eighth-most populous city in Oregon, and a metropolitan area population of 223,259,[4] making the Medford MSA the fourth largest metro area in Oregon. The city was named in 1883 by David Loring, civil engineer and right-of-way agent for the Oregon and California Railroad, after Medford, Massachusetts, which was near Loring's hometown of Concord, Massachusetts. Medford is near the middle fork of Bear Creek.[5]

History

[edit]

In 1883, a group of railroad surveyors headed by S.L. Dolson and David Loring arrived in Rock Point, near present-day Gold Hill.[6] They were charged with finding the best route through the Rogue Valley for the Oregon and California Railroad. Citizens of neighboring Jacksonville hoped that it would pass between their town and Hanley Butte, near the present day Claire Hanley Arboretum. Such a move would have all but guaranteed prosperous growth for Jacksonville, but Dolson decided instead to stake the railroad closer to Bear Creek.[7] The response from Jacksonville was mixed,[8] but the decision was final. By November 1883, a depot site had been chosen and a surveying team led by Charles J. Howard was hard at work platting the new town. They completed their work in early December 1883, laying out 82 blocks for development.[9]

James Sullivan Howard, a merchant and surveyor,[10] claimed to have built the town's first building in January 1884,[11] though blacksmith Emil Piel was advertising for business at the "central depot" in the middle of December 1883.[12] Others point out the farms of town founders Iradell Judson Phipps and Charles Wesley Broback, which were present before the town was platted.[11] Regardless, on February 6, 1884 (less than a month after it was built), J. S. Howard's store became Medford's first post office, with Howard serving as postmaster. The establishment of the post office led to the incorporation of Medford as a town by the Oregon Legislative Assembly on February 24, 1885,[13] and again as a city in 1905. Howard held the position of postmaster for Medford's first ten years, and again held the post at the time of his death on November 13, 1919.[14]

The beginning of the 20th century was a transitional period for the area. Medford built a new steel bridge over Bear Creek to replace an earlier one which washed away three years before. Without a bridge, those wanting to cross had to ford the stream, typically using a horse-drawn wagon; the first automobile did not arrive in Medford until 1903.[15] Pharmacist George H. Haskins had opened a drugstore just after the town was platted, and in 1903 he allowed the Medford Library Association to open a small library in that store. Five years later the library moved to Medford's new city hall; in another four years, Andrew Carnegie's donation allowed a dedicated library to be built. Construction on the Medford Carnegie Library was completed in 1912.[16][17]

In 1927, Medford took the title of county seat of Jackson County away from nearby Jacksonville.[5][18]

Between World War II and the 1960s, Medford had a reputation as a sundown town where African Americans and other nonwhites were not allowed to live or stay at night.[19]

In 1967,[20] Interstate 5 was completed immediately adjacent to downtown Medford to replace the Oregon Pacific Highway. It has been blamed for the decline of small businesses in downtown Medford since its completion,[20] but nevertheless remains an important route for commuters wishing to travel across the city. In fact, a study completed in 1999 found that 45% of vehicles entering I-5 from north Medford heading south exited in south Medford, just three miles (5 km) away.[21]

The high volume of traffic on Interstate 5 led to the completion of a new north Medford interchange in 2006. The project, which cost about $36 million, improved traffic flow between I-5 and Crater Lake Highway.[22] Further traffic problems identified in south Medford prompted the construction of another new interchange, costing $72 million. The project began in 2006 and was completed in 2010.[23][24][25]

Since the 1990s, Medford has dedicated an appreciable amount of resources to urban renewal in an attempt to revitalize the downtown area.[26] Several old buildings have been restored, including the Craterian Ginger Rogers Theater and the Prohibition era Cooley-Neff Warehouse, now operating as Pallet Wine Company, an urban winery. Streets have been realigned, new sidewalks, traffic signals, and bicycle lanes were installed, and two new parking garages have been built. Downtown Medford also received a new library building to replace the historic Medford Carnegie Library and now boasts satellite campuses for both Rogue Community College and Southern Oregon University.[27]

Economic problems in 2008 and 2009 put a hold on The Commons project, a collaboration between the city of Medford and Lithia Motors.[28] The project, one of the largest undertaken in downtown in recent years, aims to provide more parking, recreation, and commerce to the area. Before the work stopped, the Greyhound Bus depot was moved and $850,000 was spent replacing water lines. The Commons is anchored by the new corporate headquarters of Lithia Motors. Included in The Commons are two public park blocks slated to be informal public gathering areas as well as an area for special events such as the farmer's market. Ground breaking for the project was April 22, 2011, with a Phase 1 completion date of 2012.[28][29]

Geography

[edit]

Medford is located approximately 27 miles (43 km) north of the northern border of California.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 25.74 square miles (66.67 km2), of which 25.73 square miles (66.64 km2) is land and 0.01 square miles (0.03 km2) is water.[30]

Medford is situated in the remains of ancient volcanic flow areas as demonstrated by the Upper and Lower Table Rock lava formations and nearby Mount McLoughlin and Crater Lake, which is the remains of Mount Mazama.[31][32]

Climate

[edit]

Medford sits in a rain shadow between the Cascade Range and Siskiyou Mountains called the Rogue Valley. As such, most of the rain associated with the Pacific Northwest (and Oregon in particular) skips Medford, making it drier and sunnier than the Willamette Valley. Medford's climate is considerably warmer, both in summer and winter, than its latitude would suggest, with a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa). Summers are akin to Eastern Oregon, and winters resemble the coast. Here, summer sees an average of 61 afternoons over 90 °F (32.2 °C) and 11 afternoons over 100 °F (37.8 °C). In August 1981, the high temperature reached over 110 °F (43.3 °C) for four consecutive days,[33] with two days reaching 114 °F (45.6 °C).[34] Freezing temperatures occur on 64 mornings during an average year, and in some years there may be a day or two where the high stays at or below freezing; the average window for freezing temperatures is October 23 through April 23. The city is located in USDA hardiness zone 8.[35] Medford also experiences temperature inversions in the winter which during its lumber mill days produced fog so thick that visibility could be reduced to less than five feet (1.5 m). These inversions can last for weeks; some suggest this is because the metropolitan area has one of the lowest average wind speeds of all American metropolitan areas. The heavy fog returns nearly every winter with the inversions lowering air quality for several months without relief.[36][37][failed verification]

Medford residents experience snowfall during the winter that, due to the weather shadow effect, averages 3.4 inches (8.6 cm) and melts fairly quickly. In the past, the city has seen seasonal snowfall totals reach 31 inches (79 cm) in 1955–1956.[38] That season was also the wettest "rain year" with a total of 33.41 inches (848.6 mm); this immediately followed the driest "rain year" since records started in 1911 from July 1954 to June 1955 when only 9.28 inches (235.7 mm) was recorded. By far the wettest month has been December 1964 with 12.72 inches (323.1 mm); no other month has had more than 10 inches (254 mm). The wettest day on record has been December 2, 1962, with 3.30 inches (83.8 mm).

The lowest recorded temperature in Medford was −10 °F (−23 °C) on December 13, 1919, and the highest recorded temperature was 115 °F (46 °C) on July 20, 1946, and June 28, 2021.[39][40] There is significantly more diurnal temperature variation in summer than in winter, with the difference between December high and low average temperatures being only 13.5 °F (7.5 °C), whereas the difference between August high and low average temperatures is 33.2 °F (18.4 °C).

| Climate data for Medford, Oregon (Rogue Valley International–Medford Airport) (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1911–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

79 (26) |

86 (30) |

96 (36) |

103 (39) |

115 (46) |

115 (46) |

114 (46) |

110 (43) |

99 (37) |

80 (27) |

72 (22) |

115 (46) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 61.7 (16.5) |

67.0 (19.4) |

75.2 (24.0) |

83.6 (28.7) |

91.8 (33.2) |

98.2 (36.8) |

103.8 (39.9) |

103.4 (39.7) |

99.3 (37.4) |

86.8 (30.4) |

68.8 (20.4) |

60.9 (16.1) |

105.9 (41.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 48.2 (9.0) |

54.2 (12.3) |

59.4 (15.2) |

64.6 (18.1) |

73.9 (23.3) |

81.5 (27.5) |

91.6 (33.1) |

91.1 (32.8) |

84.3 (29.1) |

70.1 (21.2) |

54.0 (12.2) |

46.1 (7.8) |

68.3 (20.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 40.4 (4.7) |

44.1 (6.7) |

48.3 (9.1) |

52.8 (11.6) |

60.4 (15.8) |

66.9 (19.4) |

75.1 (23.9) |

74.5 (23.6) |

67.7 (19.8) |

56.1 (13.4) |

45.2 (7.3) |

39.4 (4.1) |

55.9 (13.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 32.5 (0.3) |

33.9 (1.1) |

37.2 (2.9) |

41.0 (5.0) |

46.9 (8.3) |

52.3 (11.3) |

58.6 (14.8) |

57.9 (14.4) |

51.2 (10.7) |

42.1 (5.6) |

36.4 (2.4) |

32.6 (0.3) |

43.6 (6.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 21.9 (−5.6) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

30.7 (−0.7) |

35.1 (1.7) |

42.1 (5.6) |

49.2 (9.6) |

48.7 (9.3) |

40.7 (4.8) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −3 (−19) |

−1 (−18) |

11 (−12) |

21 (−6) |

25 (−4) |

27 (−3) |

35 (2) |

37 (3) |

25 (−4) |

17 (−8) |

9 (−13) |

−10 (−23) |

−10 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.72 (69) |

1.96 (50) |

1.81 (46) |

1.51 (38) |

1.34 (34) |

0.68 (17) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.33 (8.4) |

0.48 (12) |

1.22 (31) |

2.61 (66) |

3.53 (90) |

18.43 (468) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.0 (2.5) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.9 (2.3) |

3.4 (8.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 13.5 | 11.6 | 12.6 | 11.4 | 8.7 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 7.5 | 12.9 | 14.4 | 103.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 3.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84.3 | 77.9 | 71.3 | 65.2 | 60.9 | 54.5 | 47.7 | 50.4 | 56.9 | 70.4 | 83.7 | 86.5 | 67.4 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 32.4 (0.2) |

34.2 (1.2) |

35.4 (1.9) |

37.2 (2.9) |

41.9 (5.5) |

46.2 (7.9) |

48.4 (9.1) |

48.7 (9.3) |

45.0 (7.2) |

41.4 (5.2) |

37.6 (3.1) |

33.1 (0.6) |

40.1 (4.5) |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and dew point 1961–1990)[41][42][43][44] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 967 | — | |

| 1900 | 1,791 | 85.2% | |

| 1910 | 8,840 | 393.6% | |

| 1920 | 5,756 | −34.9% | |

| 1930 | 11,007 | 91.2% | |

| 1940 | 11,281 | 2.5% | |

| 1950 | 17,305 | 53.4% | |

| 1960 | 24,425 | 41.1% | |

| 1970 | 28,973 | 18.6% | |

| 1980 | 39,746 | 37.2% | |

| 1990 | 46,951 | 18.1% | |

| 2000 | 63,154 | 34.5% | |

| 2010 | 74,907 | 18.6% | |

| 2020 | 85,824 | 14.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[45][2] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[46] | Pop 2010[47] | Pop 2020[48] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 54,299 | 59,756 | 61,433 | 85.98% | 79.77% | 71.58% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 291 | 598 | 805 | 0.46% | 0.80% | 0.94% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 607 | 691 | 687 | 0.96% | 0.92% | 0.80% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 701 | 1,084 | 1,728 | 1.11% | 1.45% | 2.01% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 142 | 328 | 487 | 0.22% | 0.44% | 0.57% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 36 | 76 | 444 | 0.06% | 0.10% | 0.52% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 1,237 | 2,055 | 5,554 | 1.96% | 2.74% | 6.47% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 5,841 | 10,319 | 14,686 | 9.25% | 13.78% | 17.11% |

| Total | 63,154 | 74,907 | 85,824 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[49] of 2010, there were 74,907 people, 30,079 households, and 19,072 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,911.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,124.1/km2). There were 32,430 housing units at an average density of 1,260.4 per square mile (486.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 86.0% White, 1.5% Asian, 1.2% Native American, 0.9% African American, 0.5% Pacific Islander, 6.0% from other races, and 3.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 13.8% of the population.

There were 30,079 households, of which 31.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.1% were married couples living together, 13.1% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 36.6% were non-families. 28.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 2.98.

The median age in the city was 37.9 years. 24.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25.4% were from 25 to 44; 25.3% were from 45 to 64; and 16.2% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.4% male and 51.6% female.

Crime

[edit]FBI data for 2015 ranked Medford as the most dangerous major city in Oregon, with 502 violent crimes and 6,543 property crimes per 100,000 residents.[50]

Medford experienced increased gang activity and organized crime in the 2000s.[51] In 2009, Medford experienced increased methamphetamine use, which was believed to have contributed to property crimes, including identity theft.[52]

Economy

[edit]

Medford's economy is driven primarily by the health care industry.[53] The two major medical centers in the city, Asante Rogue Regional Medical Center[54] and Providence Medford Medical Center, employ over 2,000 people. As Medford is also a retirement destination, assisted living and senior services have become an important part of the economy.

In the past, Medford's economy was fueled by agriculture (pears, peaches, viticulture grapes) and timber products. The largest direct marketer of fruits and food gifts in the United States, Harry and David Operations Corp., is based in Medford. It is the largest employer in Southern Oregon, with 1,700 year round and about 6,700 seasonal employees in the Medford area.[55] The recreational legalization of OR marijuana in 2012 has been a special boon for area agriculture. Of the more than two million pounds of marijuana grown in the state each year,[56] $2 million a month is sold from Medford area retailers.[57] Lithia Motors, a Fortune 500 company and the 4th largest auto retailer in the U.S.,[58] has been headquartered in Medford since 1970 and was started in Ashland in 1946, named for a nearby springs.[59][60]

Other companies located in the city include Benchmark Maps,[61] Falcon Northwest, Pacific International Enterprises, and Tucker Sno-Cat. Medford and the surrounding area is home to the expanding Oregon wine industry, which includes the Rogue Valley AVA.

The city's historic downtown has undergone an economic recovery in recent years, using a combination of public funds and private investment. The revitalization effort led to the renovation of underutilized downtown properties and to the construction of a new Lithia Motors headquarters building in the district, completed in 2012.[62] Hospitality company The Neuman Hotel Group, based in nearby Ashland, OR, took over management and ownership of a large downtown motel, The Red Lion, in 2014, that had fallen into disrepair. Neuman Hotel Group renovated the property and renamed it Inn At the Commons.[62]

Bear Creek Corporation/Harry & David

[edit]Medford is the birthplace of Bear Creek Corporation, known around the world for its fruit-laden gift baskets, especially locally grown pears.[63] Tours of the plant are open to the public.

Arts and culture

[edit]The annual Pear Blossom Run ends across the street from Alba Park at the Medford city hall, with an all-day fair conducted in the park itself.[64]

I.O.O.F. Eastwood Historic Cemetery

[edit]The cemetery, established in 1890, lies on 20 acres (8.1 ha) just north of Bear Creek Park. The Parks and Recreation Department offers free tours of the cemetery.

Medford Carnegie Library

[edit]

The Medford Carnegie Library is a two-story library building located in downtown Medford. It was erected in 1911 thanks to a gift from Andrew Carnegie, but was vacated in 2004 after a new library building was constructed near the Rogue Community College extension campus, also in downtown Medford.[65] Currently, a nonprofit, The Children's Museum of Southern Oregon (formerly Kidtime), occupies the location.[66]

Vogel Plaza

[edit]

Finished in 1997 at the intersection of E. Main St and Central Ave in downtown Medford, Vogel Plaza has quickly become a center of activity for many local events.[67]

Parks and recreation

[edit]Alba Park

[edit]The oldest park in Medford, Alba Park is located at the intersection of Holly and Main in downtown Medford was deeded to the city by the railroad company in 1888.[68] Known as Library Park after the 1911 construction of the Medford Carnegie Library, it was later renamed for Medford's sister city, Alba, Italy.[69] The park contains a gazebo, a statue of a boy with two dogs surrounded by a fountain pool, and a Japanese gun from World War II.[70][71]

Bear Creek Park

[edit]

At nearly 100 acres (0.40 km2), this south Medford park is the second largest in the city (Prescott Park is the largest at 1,740 acres).[72] Bear Creek Park is bordered on the west by Bear Creek and the Bear Creek Greenway. On the park grounds are four tennis courts, a skatepark, a dog park, an amphitheater, a large playground, a BMX track, and a community garden.[73]

Since 1925, the property hosting Bear Creek Park has been used for several purposes. The first section was purchased from a resident of Medford named Mollie Keene. The town used it for incinerating garbage until 1939. After that, it spent 20 years as a girl scout day camp before seeing private ownership again for a few years. Concerns about pollution in the Bear Creek received media attention in 1963 and the city purchased more property.[74] In 1988, a playground designed by Robert Leathers of New York was built.[75]

The Commons

[edit]

The Commons is a public park built in the city's historic downtown district adjacent to the Lithia Motors headquarters building. It has been used as a venue for community activities. It was completed in 2012.[62]

Roxy Ann Peak and Prescott Park

[edit]

One of Medford's most prominent landmarks,[76] Roxy Ann Peak is a 30-million-year-old mountain located on the east side of the city. Its summit is 3,576 feet (1,090 m) above sea level.[77][78] It was named for Roxy Ann Bowen, an early settler who lived in its foothills.[79]

A significant area of Roxy Ann Peak (including the summit) is enclosed in Medford's largest park,[80] a 1,740-acre (2.72 sq mi; 7.0 km2) protected area called Prescott Park. The land was set aside in the 1930s and named in honor of George J. Prescott, a police officer killed in the line of duty in 1933.[81]

The most commonly used trail on Roxy Ann Peak, part of Prescott Park, climbs about 950 feet (290 m) from the beginning of the footpath at the second gate to a height of about 3,547 feet (1,081 m). The trail is about 3.4 miles (5.5 km) one-way, and provides a panoramic view of the Rogue Valley.

Government

[edit]

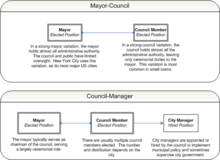

Medford has a council-manager style of government. The governing body of Medford consists of an elected mayor and eight city council members, two from each of four wards. The council hires a professional city manager to run the day-to-day operations of the city including the hiring of city staff.[82]

The mayor and council members are not paid, but are reimbursed for expenses.[82]

Mayor

[edit]The current mayor of Medford is Randy Sparacino. He was elected in November 2020. The longest serving mayor was Gary Hale Wheeler. He was first elected mayor in November 2004 with 16,653 of 28,195 votes (59%),[83] reelected in 2008 with 21,651 of 22,211 votes (97.5%),[84] reelected again in 2012 with about 97 percent of the votes,[85] and reelected again in 2016 with about 56 percent of the votes for a term ending in December 2020.[86] Notable previous mayors include Jerry Lausmann (1986–1998),[87] and Al Densmore (1977–1983).[88]

City manager

[edit]The city manager position is held by Brian Sjothun, the former Medford Parks and Recreation Director.[89]

Education

[edit]Medford is served by Medford School District 549C and has two main high schools and two alternative high schools: South Medford High School, North Medford High School, Central Medford High School, and Medford Innovation Academy respectively. In addition to the two public high schools, Medford has several private high schools. Two of the largest are St. Mary's School and Cascade Christian High School. In addition, there are 14 public elementary schools and three public middle schools, (Hedrick, Oakdale, and McLoughlin). Medford 549C has over 13,000 students enrolled as of 2012[update].

Crossroads School is a private, alternative high school operating in Medford along with three others operated or affiliated with a church; Cascade Christian High School, St. Mary's High School, and Rogue Valley Adventist School. Grace Christian and Sacred Heart School are private elementary and middle schools in Medford.[90]

In 1997, Grants Pass-based Rogue Community College (RCC) completed construction on a seven-building campus spanning five blocks in downtown Medford.[91] Nearby Ashland-based Southern Oregon University collaborated with Rogue in 2007 on the construction of an eighth building which will offer third- and fourth-year courses to students.[92] Pacific Bible College, formerly named Dove Bible Institute, was founded in Medford in 1989.[93]

Media

[edit]Television

[edit]Radio

[edit]AM

[edit]FM

[edit]- KSRG 88.3 JPR/SOU Public Radio Classical

- KSMF 89.1 JPR/SOU Public Radio Jazz

- KSOR 90.1 JPR/SOU Public Radio Classical

- KHRI 91.1 Air 1 Christian Rock

- KDOV-FM 91.7 Christian Top 40

- KTMT-FM 93.7 Now 93.7 – Top 40

- KRRM 94.7 Classic Country

- KBOY-FM 95.7 Classic Rock

- KROG 96.9 The Rogue – Active Rock

- KLDR 98.1 Top 40

- KRVC 98.9 Hot 98.9 Today's Hits

- KRWQ 100.3 Country

- KCMX-FM 101.9 Lite 102 – Adult Contemporary

- KCNA 102.7 The Drive – Classic Hits

- KLDZ 103.5 Kool 103 – Classic Hits

- KAKT 105.1 The Wolf – New Country

- KMED 106.3 News/Talk

- KIFS 107.5 KISS-FM Top 40

Newspaper

[edit]Until 2023, the principal newspaper of Medford and Jackson County was the Mail Tribune, founded in 1909.[94] It ceased publication of its print editions in September 2022 and shut down all operations on January 13, 2023.[95][96] Within days of the Mail Tribune shutting down, EO Media Group – publisher of several other newspapers in Oregon – announced that it would be launching a new newspaper, based in Medford,[97] to fill the void.[98] With print editions three days a week (Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays), the first of which was published on February 18, the new paper was initially named the Rogue Valley Tribune.[98] The owners of the former paper objected to the use of "Tribune" in the name, and on March 1, 2023, EO Media Group changed the newspaper's name to the Rogue Valley Times, in order to avoid a potential legal fight.[99][100] David Smigelski, a former editor at the Mail Tribune, was hired as managing editor of the Rogue Valley Times.[97][98]

Sports

[edit]In addition to having several athletes who were famous natives or residents of the city, Medford has played host to several professional sports teams since 1948. It was the home city for several professional baseball teams, most notably the Medford A's, later known as the Southern Oregon Timberjacks, of the Northwest League. They were a short-season single-A minor league baseball affiliate of the Oakland Athletics who played at historic Miles Field from 1979 to 1999 before relocating to Vancouver, British Columbia.

Medford also hosted a professional indoor football team from the National Indoor Football League known as the Southern Oregon Heat in 2001. They played in the Compton Arena at the Jackson County Expo Park.

Medford's Lava Lanes bowling alley previously hosted the PBA's Medford Open every January, which aired on ESPN; the last Open took place in 2009.

Medford is the home of a Junior A hockey team, the Southern Oregon Spartans, who play their home games at The RRRink in south Medford.

Medford is host to the Medford Rogues, a collegiate wood bat baseball team, who play their home games at Harry and David Field.

Each year, the Rogue Valley Timbers Soccer Club hosts the Rogue Memorial Challenge on Memorial Day weekend, culminating at US Cellular Community Sports Park after games in fields across the city.[101]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]The city of Medford is responsible for over 200 miles (322 km) of roads within its boundaries.[102]

Major highways

[edit]

Interstate 5 runs directly through the center of the city and includes a 3,229-foot (984 m) viaduct that elevates traffic above Bear Creek and the city's downtown.[103][104] There are two freeway exits in Medford, one at each side of the city. Highway 99 runs through the city's center, while Highway 62 runs through the northern portion of Medford. Highway 238 runs through the northwestern portion of Medford.

Air

[edit]Medford is home to Oregon's 3rd-busiest airport,[105] the Rogue Valley International-Medford Airport (IATA airport code: MFR). Over 1 million passengers use the airport annually.[106] Medford Airport has one asphalt runway, which handles about sixty daily flights from five airlines.[105] Medford's Airlines are Alaska Airlines (operated by Horizon Air), United Express, Delta Connection, United, American Airlines, and Allegiant Airlines.

Bus

[edit]The greater Medford metro area has been served by Rogue Valley Transportation District (RVTD) since 1975.[107] The bus system operates eight routes from Monday to Saturday, four of which travel to the nearby cities of Central Point, Jacksonville, Phoenix, Talent, Ashland, and White City.[108] All routes connect at the Front Street Transfer Station, which since October 2008 has contained Medford's Greyhound Bus depot.[109]

Rail

[edit]There are no passenger trains that route through Medford. Amtrak trains serve nearby Klamath Falls. People in Medford can board the Southwest POINT Klamath Shuttle Amtrak Thruway (an inter-city bus route) at the RVTD Front Street Transfer Station for a two-and-a-half-hour ride and guaranteed connection with Amtrak's Coast Starlight train at the Klamath Falls Amtrak Passenger Rail Station.[110] The last direct service was provided by the Southern Pacific Railroad to Portland, ending in 1956.[111][112]

Maritime

[edit]The nearest maritime port is the Port of Coos Bay, which is 167 miles (269 km) away.

The nearby Rogue River was monitored for flooding at the former Gold Ray Dam site, a decommissioned and now removed hydroelectric dam built in 1906 near Gold Hill.[113] The National Weather Service identifies 12 feet (3.6 m) as the flood level.[114] At this depth, navigability between the Pacific Ocean and the Rogue Valley is limited. Even a small "handysize" freighter is unable to make the trip,[115] and any ship hauling cargo to Medford would have to have a much smaller draw.[116] Therefore, Medford does not have a nearby maritime port.

Police Department

[edit]As of 2018, the Medford Police Department has 103 sworn police officers supported by a staff of 33 civilian employees and 30 volunteers.[117]

Sister cities

[edit]Shortly after the sister city program was established in 1960, Medford was paired up with Alba, Piedmont, Italy. The cities are 5,701 miles (9,175 km) apart and were paired based on 1960 similarities in population, geography, and climate.[118][119]

Every other year, Alba and Medford take turns exchanging students. During March and April of one year, students from Medford's high schools will visit Alba and stay with host families. Likewise, Alba students will visit Medford every other year. Sixty-seven Medford students applied for the 2007 trip to Italy, but only 24 were selected.[120]

It was former mayor of Medford John W. Snider who selected Alba during his 1957–1962 term, making a satellite phone call to Alba's former mayor Osvaldo Cagnasso.[121][122]

Notable people

[edit]This article's list of residents may not follow Wikipedia's verifiability policy. (July 2016) |

- Brad Arnsberg, baseball player and coach

- Justin Baldoni, actor

- Jeff Barry, baseball player

- Steve Bechler, baseball player

- Kent Beck, software engineer

- Bill Bowerman, track coach and Nike co-founder

- Paul Brainerd, founder of the Aldus Corporation

- Devin Cole, mixed martial artist

- Scott Davis, former CEO of United Parcel Service

- Helen M. Duncan, geologist and paleontologist

- Edwin Russell Durno, Oregon state senator and representative

- Robert G. Emmens, Doolittle raider

- Dick Fosbury, high jumper, Olympic gold medalist and inventor of the Fosbury Flop

- David Frohnmayer, former Attorney General of the state of Oregon and President of the University of Oregon

- Les Gutches, World Champion Freestyle wrestler and Olympian

- Bruce Hale, college and pro basketball player

- Page Hamilton, musician and record producer

- Marshall Holman, professional bowler and PBA Hall of Famer

- Chris Johns, Photographer and Editor-In-Chief at National Geographic

- Jon Lindstrom, actor

- Pete Loncarevich, BMX racer, and rider; lives in Medford

- Clinton "Fear" Loomis, professional Dota 2 player, won The International 2015 with Evil Geniuses

- Dave Luetkenhoelter, rock musician

- Danny Miles, basketball coach

- Jennifer Murphy, actress, former Miss Oregon and contestant on the fourth season of The Apprentice

- Bob Newland, NFL wide receiver for the New Orleans Saints

- Richard Nibley, violinist, composer and music educator

- Art Pollard, American racecar driver

- Kellin Quinn, vocalist of Sleeping With Sirens

- James A. Redden, U.S. District Court Judge, former Oregon Attorney General and State Treasurer

- Edwin Reinecke, 39th Lieutenant Governor of California[123]

- Jason James Richter, actor

- Lisa Rinna, actress, TV personality, The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills

- Ginger Rogers, Academy Award-winning actress and dancer; owned home in Medford

- Jaida Ross, 2024 Summer Olympics shot putter

- Charles Royer, former mayor of Seattle, and director of the Harvard Institute of Politics

- Mark Ryden, painter

- Braden Shipley, professional baseball player for the Cincinnati Reds

- Kyle Singler, retired professional basketball player

- Dick Skeen, former professional tennis player and teacher

- Vic Snyder, former U.S. Representative from Arkansas

- Jonathan Stark, former professional tennis player

- Scott Thurston, member of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers

- Kevin Towers, former general manager of the Arizona Diamondbacks

- Mike Whitehead, mixed martial artist

- Sandin Wilson, bass violinist and vocalist

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Quick Facts Jackson County, Medford City, Oregon". Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "About Medford". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on January 23, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ "Railroad Notes". Oregon Sentinel (Jacksonville, Oregon). Talky Tina Press. March 10, 1882. p. 3. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ "Local Items". Oregon Sentinel (Jacksonville, Oregon). Talky Tina Press. June 9, 1883. p. 3. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ "Commentary". Oregon Sentinel (Jacksonville, Oregon). Talky Tina Press. May 19, 1883. p. 3. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ "Commentary". Oregon Sentinel (Jacksonville, Oregon). Talky Tina Press. December 8, 1883. p. 3. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ "James Sullivan Howard". Southern Oregon History Revised. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Phipps-Howard War". Mail Tribune as quoted by the Talky Tina Press. Archived from the original on June 14, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ "Commentary". Democratic Times (Jacksonville, Oregon). Talky Tina Press. December 14, 1883. p. 3. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ Baker, Frank C. (1891). "Special Laws". The Laws of Oregon, and the Resolutions and Memorials of the Sixteenth Regular Session of the Legislative Assembly Thereof. Salem, Oregon: State Printer: 986. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ Riedel, Marilyn; M. Constance Guardino III. "Rogue River Communities". Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ^ "Since you asked: A bridge too many". Mail Tribune. February 8, 2008. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "A little bit of history". Mail Tribune. March 26, 2008. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "History of Medford, Oregon". Talky Tina Press. Archived from the original on June 14, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "History of Jacksonville". Jacksonville Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ^ E. A. (July 18, 1963). "'Sundown' No More". editorial. Medford Mail Tribune (regional ed.). Medford, Oregon. p. 4A. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved March 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

Medford has long had a reputation as a 'sundown town'. The reputation once was justified. ... Negroes and other racial minorities were definitely not welcome here. In some cases of record, many years ago, police officers were assigned to see that no such individuals were permitted to remain here overnight. Later, overnight lodging was denied them. They were not welcome in restaurants. And it was rare indeed that any found a way to stay here.

- ^ a b Aleccia, Jonel (January 3, 1999). "Takin' the old road". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- ^ Davis, Jim (March 12, 1999). "I-5 just another Medford street, study suggests". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- ^ "North Medford interchange ramp detour planned for January 3". Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries. January 1, 2005. Archived from the original on June 14, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- ^ Landers, Meg (April 12, 2007). "Concrete beam heads for south interchange". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- ^ "2004 State of the City". City of Medford. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ "South Medford Interchange project wraps up". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on March 26, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ^ Davis, Jim (December 13, 1998). "Lighting Up Medford". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ Achen, Paris (November 30, 2008). "RCC-SOU center impresses with its 'bells and whistles'". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Achen, Paris (August 8, 2008). "Economy halts work on The Commons". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "Middleford Commons FAQ". DowntownMedford.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ^ "Lower Table Rock". Nature.org. January 19, 2008. Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2006.

- ^ "Mount McLoughlin". United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- ^ "Oregon Hot and Cold records by month". Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ "Medford Weather In August". Archived from the original on October 6, 2011.

- ^ "What is my arborday.org Hardiness Zone?". Arbor Day Foundation. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "Average Wind Speed (MPH)". National Climatic Data Center. August 20, 2008. Archived from the original on March 10, 2009. Retrieved April 18, 2009.

- ^ Bates, Earl & Lombard, Porter (July 1978). "Evaluation of Temperature Inversions and Wind Machine on Frost Protection in Southern Oregon" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "Monthly Total Snowfall (Inches)". Western Regional Climate Center. October 18, 2007. Retrieved February 2, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ @NWSMedford (June 28, 2021). "Alright folks! After a period of premature excitement, we finally reached our rolling 5 minute average of 115! We'v…" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Pfeil, Ryan (June 28, 2021). "Medford ties all-time heat record". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on July 3, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "xmACIS2". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 15, 2019. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ "Medford Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Medford city, Oregon". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Medford city, Oregon". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Medford city, Oregon". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ^ Graves, Mark (July 12, 2017). "Oregon's 20 most crime-ridden cities ranked, according to FBI data". OregonLive.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ Burke, Anita (January 3, 2008). "Increased violence puts gang presence on radar". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ Conrad, Chris (June 8, 2009). "Medford sees 45 percent jump in drug arrests". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ "MailTribune.com: Making ends meet". Archived from the original on June 24, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ "Asante Rogue Regional Medical Center". Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Locations". Bear Creek Organization. Archived from the original on December 17, 2007. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- ^ "In Oregon, Overproduction Prompts Debate Over Cannabis Export Legislation". Cannabis Business Times. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ Mann, Damian (May 20, 2018). "Local pot industry surpasses wine". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ "Top 150 Dealership Groups" (PDF). Automotive News. March 27, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ Battistella, Edwin. "Lithia Motors". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Portland State University. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ "Our History". Lithia Motors. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ "About Benchmark Maps". Benchmark Maps. Archived from the original on August 23, 1999. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ a b c Cook, Dan. "Will Medford Ever Be Cool?". Oregon Business Magazine. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ "Harry & David | About Us". Bco.com. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ "Important Times". PearBlossomRun.com. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- ^ Fattig, Paul (March 7, 2004). "Carnegie closes the book on 92 years of service". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ^ Bulkeley, Aubrey (July 13, 2022). "The Children's Museum of Southern Oregon celebrates new home in downtown Medford". NPR. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ "Vogel Plaza". City of Medford. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ "Medford Squibs". Democratic Times (Jacksonville, Oregon). Talky Tina Press. February 10, 1888. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ^ "Appendix F: Priority maintenance projects" (PDF). City of Medford. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2007. Retrieved March 24, 2008.

- ^ "Alba Park". City of Medford. Retrieved January 18, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Since You Asked". Mail Tribune. October 12, 2000. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ "MailTribune.com: Roxy Ann shows her true colors in the spring". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

- ^ "City of Medford Oregon – Bear Creek Amphitheater, Dog Park, Skate Park". Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

- ^ Landers, Meg (July 26, 2005). "Creek Rubbish Resurfaces". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

- ^ "Best Playground". Mail Tribune. October 26, 2008. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

- ^ "Roxy Ann is named for pioneer woman". Since You Asked. Mail Tribune. January 23, 2006. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Young, Pete (April 15, 2008). "2008 Prescott Park Master Plan" (PDF). City of Medford Parks Commission. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ "Roxy Ann". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ Miller, Bill (September 23, 2007). "A View of Roxy Ann Peak". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 24, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ "Activities". Mail Tribune. August 18, 2006. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Briskley, Jill (March 16, 2003). "Rededication ceremony honors Medford's first traffic officer who was shot and killed". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ a b "About Medford's Governing Body". City of Medford. Archived from the original on October 8, 2007. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ "General Election, November 2004". Jackson County, Oregon. Archived from the original on January 5, 2011. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

- ^ "Official Election Results, November 2008". Jackson County, Oregon. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2009.

- ^ "Official Election Results: Summary Report". Jackson County, Oregon. November 6, 2012. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ "Statement of Votes Cast by Geography". Jackson County, Oregon. November 23, 2016. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ "Editorials". Mail Tribune archives. December 30, 1998. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ "Staff Directory". City of Medford. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ Mann, Damian (August 25, 2016). "Brian Sjothun named Medford city manager". MailTribune.com. Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- ^ "8Nonpublics.pmd" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 1, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ^ "Proposal for a Minor Substantive Change" (PDF). Rogue Community College. April 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 16, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ Darling, John (March 21, 2007). "RCC-SOU joint project breaks mold". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ "Pacific Bible College". Archived from the original on December 7, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- ^ Stiles, Greg (August 2, 2007). "Future of Mail Tribune's unclear". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Neumann, Erik (January 11, 2013). "Medford Mail Tribune announces it will close Friday". Oregon Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ Njus, Elliot (January 11, 2023). "Mail Tribune, storied newspaper in Medford, to abruptly shut down". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Gerry (January 30, 2023). "Long-time journalist to run Rogue Valley Tribune in Medford". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c Blinder, Mike (February 18, 2023). "Medford, Oregon: As one paper dies, another begins all in a few weeks". Editor & Publisher. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Manning, Jeff (March 1, 2023). "Startup newspaper in Medford to change name, publisher cites legal threats". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on March 2, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ "Rogue Valley Tribune has a new name". rv-times.com. EO Media Group. March 1, 2023. Archived from the original on March 16, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Rogue Memorial Challenge http://www.roguememorialchallenge.com/home.php. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Utility accounts". s City of Medford. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ "Interstate 5". State of Oregon Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on December 4, 2006. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- ^ "The Interstate in Oregon". State of Oregon. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- ^ a b "General Information". 5 Jackson County Airport Page. Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- ^ "StackPath". January 4, 2019. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ "About Us". g Rogue Valley Transportation District. Archived from the original on March 12, 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ "Bus Schedules". g Rogue Valley Transportation District. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ Achen, Paris (September 25, 2008). "Greyhound unveils new Medford bus station". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "South West Point, operated by the Klamath Shuttle". Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved April 24, 2010.

- ^ Southern Pacific timetable, February 6, 1952, Tables 78, 81

- ^ Streamliner Schedules, 'The Rogue River,' from the 'Official Guide,' http://www.streamlinerschedules.com/concourse/track7/rogueriver195504.html Archived January 22, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Freeman, Mark (March 7, 2008). "Future of Gold Ray Dam up in air". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ "Rogue River at Gold Ray". s/ Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service. National Weather Service. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ The summer draft of typical handysize cargo ships can easily reach 10 meters (33 feet).

- ^ Solliday, Louise (September 7, 2007). "Availability and Content of Draft Navigability Study Report" (PDF). Oregon Department of State Lands. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ "Medford Police Department". City of Medford. Archived from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Oregon Sister Relationships—Organized by Country". State of Oregon, Economic and Community Development Department. Archived from the original on May 19, 2007.

- ^ "Our Sister City". s City of Medford. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ Achen, Paris (February 27, 2007). "Medford students off to Italy". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ "Old dairy holds fond memories". Mail Tribune. February 16, 1999. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ "Council welcomes mayor Rossetto and youth from Alba, Italy" (PDF). City of Medford Quarterly Newsletter. s City of Medford. October 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved March 24, 2008.

- ^ "REINECKE, Edwin | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on August 23, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.