Max Dupain

Max Dupain AC OBE | |

|---|---|

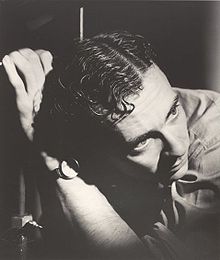

Dupain in 1937 | |

| Born | Maxwell Spencer Dupain 22 April 1911 Ashfield, New South Wales, Australia |

| Died | 27 July 1992 (aged 81) |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Occupation | photographer |

| Notable work | Sunbaker |

| Parents |

|

Maxwell Spencer Dupain AC OBE (22 April 1911 – 27 July 1992) was an Australian modernist photographer.

Early life

[edit]Dupain received his first camera as a gift in 1924, spurring his interest in photography.[1] He later joined the Photographic Society of NSW, where he was taught by Justin Newlan; after completing his tertiary studies, he worked for Cecil Bostock in Sydney.

Career

[edit]Early years

[edit]

By 1934 Max Dupain had struck out on his own and opened a studio in Bond Street, Sydney. In 1937, while on the south coast of New South Wales, he photographed the head and shoulders of an English friend, Harold Salvage, lying on the sand at Culburra Beach. But it was not until the 1970s that the photograph began to receive wide recognition. A print of the photograph was purchased in 1976 by the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra and by the 1990s it had cemented its place as an iconic image of Australia.[2] An early vintage print of the original version of the Sunbaker is contained in an album of photographs donated to the State Library of New South Wales by Dupain's friend, the architect Chris Vandyke.[3]

Later years

[edit]

During World War II Dupain served with the Royal Australian Air Force in both Darwin and Papua New Guinea helping to create camouflage.

The war affected Dupain and his photography, by creating in him a greater awareness of truth in documentary. In 1947, these feelings were reinforced when he read a book Grierson on Documentary which defined the need for photography without pretence. The catchcry was "the creative treatment of actuality". Dupain was keen to restart the studio with this new perspective and abandon what he called the "cosmetic lie of fashion photography or advertising illustration". Refusing to return to the "cosmetic lie" of advertising, Dupain said:

"Modern photography must do more than entertain, it must incite thought and by its clear statements of actuality, cultivate a sympathetic understanding of men and women and the life they live and create."

Dupain's documentary work of this period is exemplified in his photograph "Meat Queue". He used a more naturalistic style of photography, "capturing a moment of everyday interaction [rather than] attempting any social comment".[4]

Dupain also worked extensively for the University of New South Wales[5] and CSR Limited and made many trips to the interior and coast of northern Australia. However, apart from his war service he rarely left Australia, the first time not until 1978, when he was 67, and even then it was to photograph the new Australian Embassy in Paris, designed by his longtime friend and associate Harry Seidler.[6] He wrote, "I find that my whole life, if it is going to be of any consequence in photography, has to be devoted to that place where I have been born, reared and worked, thought, philosophised and made pictures to the best of my ability. And that's all I need".[7]

In the 1950s the advent of the new consumerism meant that there was plenty of promotional photography for advertising and he attracted clients from magazines, advertising agencies and industrial firms. In between this he devoted time to pursue his love of architecture, and began architectural photography, which he continued most of his life.

The State Library of New South Wales holds the most significant archive of Max Dupain's work.[8][9][10] In June 2016 it was announced that the State Library now holds the entire photographic collection of Max Dupain (1911–1992). This now adds the Max Dupain Exhibition Archive of 28,000 negatives including the Sunbaker and Bondi, 1939, as well as lesser-known photographs such as his fantastic record of Penrith in Sydney's west in 1948. These images join existing collections of Dupain's commercial and architectural photography, studio portraits, and his record of the Ballets Russes.[11]

Max Dupain's began using Linhof Technica 4x5 camera in 1959 and it quickly became his 'go to' camera for architectural photography until the 1980s, including his well known documentary photography of the Sydney Opera House and workers during its construction from 1959 to 1973. This camera is now a part of Sydney Powerhouse Museum collection.[12]

Dupain continued working until his death in 1992.

Personal life

[edit]In 1939, after the outbreak of World War II, Dupain married Olive Cotton (also a photographer) but they divorced soon after. A decade later, Dupain married Diana Illingworth and subsequently they had a daughter Danina and a son Rex, who also became a photographer.

Honours

[edit]Dupain was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1982 New Year Honours list.[13][14]

He was made a Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) in the Australia Day Honours 1992.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ "Max Dupain". Tristans Gallery. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ^ Max Dupain (1937). "Sunbaker". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ^ Media Release (2014). Holy grail of Australian photography in NSW State Library hands (PDF). State Library of New South Wales.

- ^ Max Dupain (1946). "Meat Queue". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ^ O'Farrell, Patrick (1999). "3". UNSW - A Portrait. University of New South Wales Press Ltd. p. 116. ISBN 0-86840-617-1. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ Richard Yallop, "The pleasures of Dupain", The Weekend Australian, 23–24 September 2000

- ^ Sebastian Smee, "On the beach", Good Weekend magazine, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 October 2000

- ^ Jill White (1991). Max Dupain : modernis. Print Room Press, Woolloomooloo, Sydney.

- ^ Alan Davies (2003). Max Dupain's Australians. State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

- ^ Avryl Whitnall (2007). Max Dupain : modernis. State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

- ^ "Maximum Dupain". SL Magazine. 9 (3): 6. Spring 2016.

- ^ "'Linhof Technika' camera used by Max Dupain". collection.maas.museum. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "It's an Honour - Honours - Search Australian Honours". It's an Honour. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "It's an Honour - Honours - Search Australian Honours". It's an Honour. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ It's an Honour: AC. Retrieved 7 April 2020

Max Dupain Archival Collections

[edit]- Max Dupain and Associates records and negative archive, taken before 30 July 1998, approximately 155,000 Negatives, including transparencies in 973 boxes, held by the State Library of New South Wales PXA 2155 PXE 1679

- Max Dupain Exhibition Negative Archive of film and glass plate negatives, 29024 negatives, 2150 photographic prints, and some textual material, ca 1920–1992, held by the State Library of New South Wales 1037031

- Max Dupain archive of photographs and photo negatives (Series 2), State Library of New South Wales 414306

- Max Dupain, collection of photographs of Sydney and Manly, ca. 1938–1949, 1970 and 1988, State Library of New South Wales PXD 965/1-20

- Collection of photographs from the studio of Max Dupain and Associates, 1947–1968, State Library of New South Wales PXD 720

- Architectural photographs by Max Dupain, 1939–1988, State Library of New South Wales PXD 1013

- Camping trips on Culburra Beach, N.S.W., 1937, State Library of New South Wales PXA 1951

- Papers of Max Dupain, 1937, Art Gallery of New South Wales Library, access-date=10 November 2021

Bibliography

[edit]For a full list, see [1]:

- Max Dupain’s Australian Landscapes, Mead and Beckett, Australia, 1988.

- Fine Houses of Sydney, Irving Robert; Kinstler John; Dupain Max, Methuen, Sydney, 1982.

- Max Dupain Photographs published by Ure Smith, Sydney, 1948.