Midwifery

A pregnancy check-up by a midwife in a birth center | |

| Focus | |

|---|---|

| Specialist | Midwife |

Midwifery is the health science and health profession that deals with pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period (including care of the newborn),[1] in addition to the sexual and reproductive health of women throughout their lives.[2] In many countries, midwifery is a medical profession[3][4][5][6][7] (special for its independent and direct specialized education; should not be confused with the medical specialty, which depends on a previous general training). A professional in midwifery is known as a midwife.

A 2013 Cochrane review concluded that "most women should be offered midwifery-led continuity models of care and women should be encouraged to ask for this option although caution should be exercised in applying this advice to women with substantial medical or obstetric complications."[8] The review found that midwifery-led care was associated with a reduction in the use of epidurals, with fewer episiotomies or instrumental births, and a decreased risk of losing the baby before 24 weeks' gestation. However, midwifery-led care was also associated with a longer mean length of labor as measured in hours.[8]

Main areas of midwifery

[edit]Pregnancy

[edit]First trimester

[edit]Trimester means "three months". A normal pregnancy lasts about nine months and has three trimesters.[9]

First trimester screening varies by country. Women are typically offered urinalysis (UA) and blood tests including a complete blood count (CBC), blood typing (including Rh screen), syphilis, hepatitis, HIV, and rubella testing.[9] Additionally, women may have chlamydia testing via a urine sample, and women considered at high risk are screened for sickle cell disease and thalassemia.[9] Women must consent to all tests before they are carried out. The woman's blood pressure, height and weight are measured. Her past pregnancies and family, social, and medical history are discussed. Women may have an ultrasound scan during the first trimester which may be used to help find the estimated due date. Some women may have genetic testing, such as screening for Down syndrome. Diet, exercise, and common disorders of pregnancy such as morning sickness are discussed.[9]

Second trimester

[edit]The mother visits the midwife monthly or more often during the second trimester. The mother's partner and/or the birth companion may accompany her. The midwife will discuss pregnancy issues such as fatigue, heartburn, varicose veins, and other common problems such as back pain. Blood pressure and weight are monitored and the midwife measures the mother's abdomen to see if the baby is growing as expected. Lab tests such as a UA, CBC, and glucose tolerance test are done if clinically indicated.[10]

Third trimester

[edit]In the third trimester the midwife will see the mother every two weeks until week 36 and every week after that. Weight, blood pressure, and abdominal measurements will continue to be done. Lab tests such as a CBC and UA may be done with additional testing done for at-risk pregnancies. The midwife palpates the woman's abdomen to establish the lie, presentation and position of the fetus and later, the engagement. A pelvic exam may be done to see if the mother's cervix is dilating.[11] The midwife and the mother discuss birthing options and write a birth care plan.[citation needed]

Childbirth

[edit]Labor and delivery

[edit]

Midwives are qualified to assist with a normal vaginal delivery while more complicated deliveries are handled by a health care provider who has had further training. Childbirth is divided into four stages.

- First stage of labor The first stage of labour involves the opening of the cervix.[12] In the early parts of this stage the cervix will become soft and thin thus preparing for the delivery of the baby.[12] The first stage of labour is complete when the cervix has dilated the full 10cm.[12] During the first stage of labor the mother begins to feel strong and regular contractions that come every 5 to 20 minutes and last 30 to 60 seconds. Contractions gradually become stronger, more frequent, and longer lasting.

- Second stage of labor During the second stage the baby begins to move down the birth canal. As the baby moves to the opening of the vagina it "crowns", meaning the top of the head can be seen at the vaginal entrance. At one time an "episiotomy", (an incision in the tissue at the opening of the vagina) was done routinely because it was believed that it prevented excessive tearing and healed more readily than a natural tear.[13] However, more recent research shows that a surgical incision may be more extensive than a natural tear, and is more likely to contribute to later incontinence and pain during sex than a natural tear would have.[13]

- The midwife assists the baby as needed and when fully emerged, cuts the umbilical cord. If desired, either of the baby's parents may cut the cord. In the past the cord was cut shortly after birth, but there is growing evidence that delayed cord clamping may benefit the infant.[14]

- Third stage of labor The third stage of labour is where the mother must deliver the placenta.[12] In order for the mother to do this they may need to push. Just like the contractions in the first stage of labour they may experience one or two of these.[12] The midwife may assist the mother in delivering the placenta by gently pulling on the umbilical cord.[12]

- Fourth stage of labor The fourth stage of labor is the period beginning immediately after the birth and extending for about six weeks. The World Health Organization describes this period as the most critical and yet the most neglected phase in the lives of mothers and babies.[15] Until recently babies were routinely removed from their mothers following birth, however beginning around 2000, some authorities began to suggest that early skin-to-skin contact (placing the naked baby on the mother's chest) is of benefit to both mother and infant. As of 2014, early skin-to-skin contact is endorsed by all major organizations that are responsible for the well-being of infants.[16] Thus, to help establish bonding and successful breastfeeding, the midwife carries out immediate mother and infant assessments as the infant lies on the mother's chest and removes the infant for further observations only after they have had their first breastfeed.

Following the birth, if the mother had an episiotomy or a tearing of the perineum, it is sutured. The midwife does regular assessments for uterine contraction, fundal height,[17] and vaginal bleeding.[18] Throughout labor and delivery the mother's vital signs (temperature, blood pressure, and pulse) are closely monitored and her fluid intake and output are measured. The midwife also monitors the baby's pulse rate, palpates the mother's abdomen to monitor the baby's position, and does vaginal examinations as indicated. If the birth deviates from the norm at any stage, the midwife requests assistance from the multi-disciplinary team.

Birthing positions

[edit]Until the last century most women have used both the upright position and alternative positions to give birth. The lithotomy position was not used until the advent of forceps in the seventeenth century and since then childbirth has progressively moved from a woman supported experience in the home to a medical intervention within the hospital. There are significant advantages to assuming an upright position in labor and birth, such as stronger and more efficient uterine contractions aiding cervical dilatation, increased pelvic inlet and outlet diameters and improved uterine contractility.[19] Upright positions in the second stage include sitting, squatting, kneeling, and being on hands and knees.[20]

Postpartum period

[edit]For women who have a hospital birth, the minimum hospital stay is six hours. Women who leave before this do so against medical advice. Women may choose when to leave the hospital. Full postnatal assessments are conducted daily whilst inpatient, or more frequently if needed. A postnatal assessment includes the woman's observations, general well-being, breasts (either a discussion and assistance with breastfeeding or a discussion about lactation suppression), abdominal palpation (if she has not had a caesarean section) to check for involution of the uterus, or a check of her caesarean wound (the dressing does not need to be removed for this), a check of her perineum, particularly if she tore or had stitches, reviewing her lochia, ensuring she has passed urine and had her bowels open and checking for signs and symptoms of a DVT. The baby is also checked for jaundice, signs of adequate feeding, or other concerns. The baby has a nursery exam between six and seventy two hours of birth to check for conditions such as heart defects, hip problems, or eye problems.[21]

In the community, the community midwife sees the woman at least until day ten. This does not mean she sees the woman and baby daily, but she cannot discharge them from her care until day ten at the earliest. Postnatal checks include neonatal screening test (NST, or heel prick test) around day five. The baby is weighed and the midwife plans visits according to the health and needs of mother and baby. They are discharged to the care of the health visitor.[22]

Care of the newborn

[edit]At birth, the baby receives an Apgar score at, at the least, one minute and five minutes of age.[23] This is a score out of 10 that assesses the baby on five different areas—each worth between 0 and 2 points. These areas are: colour, respiratory effort, tone, heart rate, and response to stimuli.[24] The midwife checks the baby for any obvious problems, weighs the baby, and measure head circumference. The midwife ensures the cord has been clamped securely and the baby has the appropriate name tags on (if in hospital). Babies lengths are not routinely measured. The midwife performs these checks as close to the mother as possible and returns the baby to the mother quickly. Skin-to-skin is encouraged, as this regulates the baby's heart rate, breathing, oxygen saturation, and temperature—and promotes bonding and breastfeeding.[citation needed]

In some countries, such as Chile, the midwife is the professional who can direct neonatal intensive care units. This is an advantage for these professionals, who can use the knowledge of perinatology to bring a high quality care of the newborn, with medical or surgical conditions.[25]

Midwifery-led continuity of care

[edit]

Midwifery-led continuity of care is where one or more midwives have the primary responsibility for the continuity of care for childbearing women, with a multidisciplinary network of consultation and referral with other health care providers. This is different from "medical-led care" where an obstetrician or family physician is primarily responsible. In "shared-care" models, responsibility may be shared between a midwife, an obstetrician and/or a family physician.[8] The midwife is part of very intimate situations with the mother. For this reason, many say that the most important thing to look for in a midwife is comfort with them, as one will go to them with every question or problem.[26]

According to a Cochrane review of public health systems in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, "most women should be offered midwifery-led continuity models of care and women should be encouraged to ask for this option although caution should be exercised in applying this advice to women with substantial medical or obstetric complications." Midwifery-led care has effects including the following:[8]

- a reduction in the use of epidurals, with fewer episiotomies or instrumental births.

- a longer mean length of labour as measured in hours

- increased chances of being cared for in labour by a midwife known by the childbearing woman

- increased chances of having a spontaneous vaginal birth

- decreased risk of preterm birth

- decreased risk of losing the baby before 24 weeks' gestation, although there appears to be no differences in the risk of losing the baby after 24 weeks or overall

There was no difference in the number of Caesarean sections. All trials in the Cochrane review included licensed midwives, and none included lay or traditional midwives. Also, no trial included out of hospital birth.[8]

Compared to women in other care models, women in continuity models of midwifery care are more satisfied with their care. The updated version of the Cochrane review also shows a cost-saving effect in continuity models, compared to other midwifery models of care.[27]

In continuity models of midwifery care, the midwife-woman relationship is developing over time. The deepened relationship has shown to be of great importance and is in a systematic review described as "the viechle through which personalised care, trust and empowerment are achieved in the continuity of care midwifery model".[28]

In some cultures, midwifery is the most traditional way of carrying out a pregnancy and childbirth, and it has been conducted for multiple generations. Child birthing women in these cultures, take Zimbabwe for example, feel that health facilities are not as comforting as cultural roots of care.[29] Also, according to the World Health Organization, women should be able to have their children where ever they feel the most safe, so if having a midwife and proceeding with an at-home birth is what makes some women feel safe, then midwifery-led continuity of care might be the best option for them.[30]

History

[edit]Ancient history

[edit]

In ancient Egypt, midwifery was a recognized female occupation, as attested by the Ebers Papyrus which dates from 1900 to 1550 BCE. Five columns of this papyrus deal with obstetrics and gynecology, especially concerning the acceleration of parturition (the action or process of giving birth to offspring) and the birth prognosis of the newborn. The Westcar papyrus, dated to 1700 BCE, includes instructions for calculating the expected date of confinement and describes different styles of birth chairs. Bas reliefs in the royal birth rooms at Luxor and other temples also attest to the heavy presence of midwifery in this culture.[31]

Midwifery in Greco-Roman antiquity covered a wide range of women, including old women who continued folk medical traditions in the villages of the Roman Empire, trained midwives who garnered their knowledge from a variety of sources, and highly trained women who were considered physicians.[32] However, there were certain characteristics desired in a "good" midwife, as described by the physician Soranus of Ephesus in the 2nd century. He states in his work, Gynecology, that "a suitable person will be literate, with her wits about her, possessed of a good memory, loving work, respectable and generally not unduly handicapped as regards her senses [i.e., sight, smell, hearing], sound of limb, robust, and, according to some people, endowed with long slim fingers and short nails at her fingertips." Soranus also recommends that the midwife be of sympathetic disposition (although she need not have borne a child herself) and that she keep her hands soft for the comfort of both mother and child.[33] Pliny, another physician from this time, valued nobility and a quiet and inconspicuous disposition in a midwife.[34] There appears to have been three "grades" of midwives present: The first was technically proficient; the second may have read some of the texts on obstetrics and gynecology; but the third was highly trained and reasonably considered a medical specialist with a concentration in midwifery.[34]

Agnodice or Agnodike (Gr. Ἀγνοδίκη) was the earliest historical, and likely apocryphal,[35] midwife mentioned among the ancient Greeks.[36]

Midwives were known by many different titles in antiquity, ranging from iatrinē (Gr. nurse), maia (Gr., midwife), obstetrix (Lat., obstetrician), and medica (Lat., doctor).[37] It appears as though midwifery was treated differently in the Eastern end of the Mediterranean basin as opposed to the West. In the East, some women advanced beyond the profession of midwife (maia) to that of gynaecologist (iatros gynaikeios, translated as women's doctor), for which formal training was required. Also, there were some gynecological tracts circulating in the medical and educated circles of the East that were written by women with Greek names, although these women were few in number. Based on these facts, it would appear that midwifery in the East was a respectable profession in which respectable women could earn their livelihoods and enough esteem to publish works read and cited by male physicians. In fact, a number of Roman legal provisions strongly suggest that midwives enjoyed status and remuneration comparable to that of male doctors.[33] One example of such a midwife is Salpe of Lemnos, who wrote on women's diseases and was mentioned several times in the works of Pliny.[34]

However, in the Roman West, information about practicing midwives comes mainly from funerary epitaphs. Two hypotheses are suggested by looking at a small sample of these epitaphs. The first is the midwifery was not a profession to which freeborn women of families that had enjoyed free status of several generations were attracted; therefore it seems that most midwives were of servile origin. Second, since most of these funeral epitaphs describe the women as freed, it can be proposed that midwives were generally valued enough, and earned enough income, to be able to gain their freedom. It is not known from these epitaphs how certain slave women were selected for training as midwives. Slave girls may have been apprenticed, and it is most likely that mothers taught their daughters.[33]

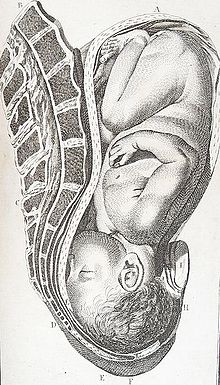

The actual duties of the midwife in antiquity consisted mainly of assisting in the birthing process, although they may also have helped with other medical problems relating to women when needed. Often, the midwife would call for the assistance of a physician when a more difficult birth was anticipated. In many cases the midwife brought along two or three assistants.[38] In antiquity, it was believed by both midwives and physicians that a normal delivery was made easier when a woman sat upright. Therefore, during parturition, midwives brought a stool to the home where the delivery was to take place. In the seat of the birthstool was a crescent-shaped hole through which the baby would be delivered. The birthstool or chair often had armrests for the mother to grasp during the delivery. Most birthstools or chairs had backs which the patient could press against, but Soranus suggests that in some cases the chairs were backless and an assistant would stand behind the mother to support her.[33] The midwife sat facing the mother, encouraging and supporting her through the birth, perhaps offering instruction on breathing and pushing, sometimes massaging her vaginal opening, and supporting her perineum during the delivery of the baby. The assistants may have helped by pushing downwards on the top of the mother's abdomen.

Finally, the midwife received the infant, placed it in pieces of cloth, cut the umbilical cord, and cleansed the baby.[34] The child was sprinkled with "fine and powdery salt, or natron or aphronitre" to soak up the birth residue, rinsed, and then powdered and rinsed again. Next, the midwives cleared away any and all mucus present from the nose, mouth, ears, or anus. Midwives were encouraged by Soranus to put olive oil in the baby's eyes to cleanse away any birth residue, and to place a piece of wool soaked in olive oil over the umbilical cord. After the delivery, the midwife made the initial call on whether or not an infant was healthy and fit to rear. She inspected the newborn for congenital deformities and testing its cry to hear whether or not it was robust and hearty. Ultimately, midwives made a determination about the chances for an infant's survival and likely recommended that a newborn with any severe deformities be exposed.[33]

A 2nd-century terracotta relief from the Ostian tomb of Scribonia Attice, wife of physician-surgeon M. Ulpius Amerimnus, details a childbirth scene. Scribonia was a midwife and the relief shows her in the midst of a delivery. A patient sits in the birth chair, gripping the handles and the midwife's assistant stands behind her providing support. Scribonia sits on a low stool in front of the woman, modestly looking away while also assisting the delivery by dilating and massaging the vagina, as encouraged by Soranus.[34]

The services of a midwife were not inexpensive; this fact that suggests poorer women who could not afford the services of a professional midwife often had to make do with female relatives. Many wealthier families had their own midwives. However, the vast majority of women in the Greco-Roman world very likely received their maternity care from hired midwives. They may have been highly trained or possessed only a rudimentary knowledge of obstetrics. Also, many families had a choice of whether or not they wanted to employ a midwife who practiced the traditional folk medicine or the newer methods of professional parturition.[33] Like a lot of other factors in antiquity, quality gynecological care often depended heavily on the socioeconomic status of the patient.

Post-classical history

[edit]

Modern history

[edit]From the 18th century, a conflict between surgeons and midwives arose, as medical men began to assert that their modern scientific techniques were better for mothers and infants than the folk medicine practiced by midwives.[41][42] As doctors and medical associations pushed for a legal monopoly on obstetrical care, midwifery became outlawed or heavily regulated throughout the United States and Canada.[43][44] In Northern Europe and Russia, the situation for midwives was a little easier - in the Duchy of Estonia in Imperial Russia, Professor Christian Friedrich Deutsch established a midwifery school for women at the University of Dorpat in 1811, which existed until World War I. It was the predecessor for the Tartu Health Care College. Training lasted for 7 months and in the end a certificate for practice was issued to the female students. Despite accusations that midwives were "incompetent and ignorant",[45] some argued that poorly trained surgeons were far more of a danger to pregnant women.[46] In 1846, the physician Ignaz Semmelweiss observed that more women died in maternity wards staffed by male surgeons than by female midwives, and traced these outbreaks of puerperal fever back to (then all-male) medical students not washing their hands properly after dissecting cadavers, but his sanitary recommendations were ignored until acceptance of germ theory became widespread.[47][48]

The argument that surgeons were more dangerous than midwives lasted until the study of bacteriology became popular in the early 1900s and hospital hygiene was improved. Women began to feel safer in the setting of the hospitals with the amount of aid and the ease of birth that they experienced with doctors.[citation needed] "Physicians trained in the new century found a great contrast between their hospital and obstetrics practice in women's homes where they could not maintain sterile conditions or have trained help."[49] German social scientists Gunnar Heinsohn and Otto Steiger theorize that midwifery became a target of persecution and repression by public authorities because midwives possessed highly specialized knowledge and skills regarding not only assisting birth, but also contraception and abortion.[50]

Contemporary

[edit]At late 20th century, midwives were already recognized as highly trained and specialized professionals in obstetrics. However, at the beginning of the 21st century, the medical perception of pregnancy and childbirth as potentially pathological and dangerous still dominates Western culture. Midwives who work in hospital settings also have been influenced by this view, although by and large they are trained to view birth as a normal and healthy process. While midwives play a much larger role in the care of pregnant mothers in Europe than in America, the medicalized model of birth still has influence in those countries, even though the World Health Organization recommends a natural, normal and humanized birth.[51]

The midwifery model of pregnancy and childbirth as a normal and healthy process plays a much larger role in Sweden and the Netherlands than the rest of Europe, however. Swedish midwives stand out, since they administer 80 percent of prenatal care and more than 80 percent of family planning services in Sweden. Midwives in Sweden attend all normal births in public hospitals and Swedish women tend to have fewer interventions in hospitals than American women. The Dutch infant mortality rate is one of the lowest rate in the world, at 4.0 deaths per thousand births, while the United States ranked twenty-second. Midwives in the Netherlands and Sweden owe a great deal of their success to supportive government policies.[52]

See also

[edit]- Afghanistan Midwifery Project

- Childbirth and obstetrics in antiquity

- Global Library of Women's Medicine

- International Confederation of Midwives

- Obstetrics

- Midwifery in Maya society

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Definition of Midwifery". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "International Definition of the Midwife". International Confederation of Midwives. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Die Hebamme in Belgien". Belgian Midwives Association (BMA). Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Vecmātes specialitātes nolikums". Latvijas Vecmāšu Asociācija. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Les compétences des sages-femmes". Ordre des sages-femmes. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Bacheloropleiding Verloskunde". Academie Verloskunde Maastricht. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Waarom Verloskunde?". Academie Verloskunde Amsterdam Groningen. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Sandall, Jane; Soltani, Hora; Gates, Simon; Shennan, Andrew; Devane, Declan (2013). "Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8 (8): CD004667. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub3. PMID 23963739.

- ^ a b c d "Prenatal care in your first trimester". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 1 July 1015. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Prenatal care in your second trimester". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 1 July 2015. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Prenatal care in your third trimester". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Stages of Labour". The women's: The Royal Women's Hospital. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ a b Mayo Clinic staff (30 July 2015). "Labor and delivery, postpartum care". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Mozes, Alan (26 May 2015). "Delaying Umbilical Cord Clamping Might Boost Child Development". Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ WHO. "WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn". WHO. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Phillips, Raylene. "Uninterrupted Skin-to-Skin Contact Immediately After Birth". Medscape. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ "Postpartum Assessment". ATI Nursing Education. Archived from the original on 2014-12-24. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ Mayo clinic staff. "Postpartum care: What to expect after a vaginal delivery". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Searle, Lorraine (April 2010). "Factors influencing maternal positions during labor". Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Gelis, Jacues. History of Childbirth. Boston: Northern University Press, 1991: 122-134

- ^ "Normal and Abnormal Puerperium: Overview, Routine Postpartum Care, Hemorrhage". 2022-01-18. Archived from the original on 2017-11-09. Retrieved 2022-10-05.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Episiotomy: When it's needed, when it's not - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Archived from the original on 2022-10-05. Retrieved 2022-10-05.

- ^ "The Apgar Score". www.acog.org. Archived from the original on 2022-10-05. Retrieved 2022-10-05.

- ^ Simon, Leslie V.; Hashmi, Muhammad F.; Bragg, Bradley N. (2022), "APGAR Score", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262097, archived from the original on 2022-07-26, retrieved 2022-10-05

- ^ "Midwifery in Chile - A Successful Experience to Improve Women ́s Sexual and Reproductive Health: Facilitators & Challenges". Journal of Asian Midwives (JAM). 3 (1): 63–69. June 2016. Archived from the original on 2023-10-29. Retrieved 2022-10-05.

- ^ "The midwife: Your best friend in natal care". 2010-10-05. Archived from the original on 2017-10-05. Retrieved 2017-10-04.

- ^ Sandall, Jane; Soltani, Hora; Gates, Simon; Shennan, Andrew; Devane, Declan (2016-04-28). Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group (ed.). "Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (4): CD004667. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5. PMC 8663203. PMID 27121907.

- ^ Perriman, Noelyn; Davis, Deborah Lee; Ferguson, Sally (2018-07-01). "What women value in the midwifery continuity of care model: A systematic review with meta-synthesis". Midwifery. 62: 220–229. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2018.04.011. ISSN 0266-6138. PMID 29723790. S2CID 13659050.

- ^ Musie, Maurine R.; Peu, Mmapheko D.; Bhana-Pema, Varshika (2022-04-25). "Culturally appropriate care to support maternal positions during the second stage of labour: Midwives' perspectives in South Africa". African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine. 14 (1): e1–e9. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v14i1.3292. ISSN 2071-2936. PMC 9082223. PMID 35532110.

- ^ Meroz, Michal (Rosie); Gesser-Edelsburg, Anat (2015). "Institutional and Cultural Perspectives on Home Birth in Israel". The Journal of Perinatal Education. 24 (1): 25–36. doi:10.1891/1058-1243.24.1.25. ISSN 1058-1243. PMC 4720861. PMID 26937159.

- ^ Jean Towler and Joan Bramall, Midwives in History and Society (London: Croom Helm, 1986), p. 9

- ^ Rebecca Flemming, Medicine and the Making of Roman Women (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 359

- ^ a b c d e f Valerie French, "Midwives and Maternity Care in the Roman World" (Helios, New Series 12(2), 1986), pp. 69-84

- ^ a b c d e Ralph Jackson, Doctors and Diseases in the Roman Empire (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988), p. 97

- ^ "Women in Medicine". www.hsl.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-04-03. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Greenhill, William Alexander (1867). "Agnodice". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 1. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 74. Archived from the original on 2012-10-07. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Rebecca Flemming, Medicine and the Making of Roman Women (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 421-424

- ^ Towler and Bramall, p.12

- ^ Medical practitioners were subjected to more regulation in the Middle Ages, especially women that had not received proper schooling in their desired medical fields. Although the medical field was becoming a male monopoly with these regulations, midwifery was still dominated by women, as men had not had schooling or education in obstetrics.

- ^ Minkowski, W L (February 1992). "Women healers of the middle ages: selected aspects of their history". American Journal of Public Health. 82 (2): 292–293. doi:10.2105/ajph.82.2.288. PMC 1694293. PMID 1739168.

- ^ Van Teijlingen, Edwin R.; Lowis, George W.; McCaffery, Peter G. (2004). Midwifery and the Medicalization of Childbirth: Comparative Perspectives. Nova Publishers. ISBN 9781594540318.

- ^ Borst, Charlotte G. (1995). Catching Babies: The Professionalization of Childbirth, 1870-1920. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674102620.

- ^ Ehrenreich, Barbara; Deirdre English (2010). Witches, Midwives and Nurses: A History of Women Healers (2nd ed.). The Feminist Press. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-0-912670-13-3.

- ^ Rooks, Judith Pence (1997). Midwifery and childbirth in America. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 422. ISBN 1-56639-711-1.

- ^ Varney, Helen (2004). Varney's midwifery (4th ed.). Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett. p. 7. ISBN 0-7637-1856-4.

- ^ Williams, J. Whitridge (1912). "The Midwife Problem and Medical Education in the United States". American Association for Study and Prevention of Infant Mortality: Transactions of the Second Annual Meeting: 165–194.

- ^ Davis, Rebecca. "The Doctor Who Championed Hand-Washing And Briefly Saved Lives". NPR. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Historical perspective on hand hygiene in health care (2009). WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge Clean Care Is Safer Care. Geneva: World Health Organization. p. 4. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Leavitt, Judith W. (1988). Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America, 1750-1950. Book: Oxford University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0195056907.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn/Otto Steiger: "Witchcraft, Population Catastrophe and Economic Crisis in Renaissance Europe: An Alternative Macroeconomic Explanation.", University of Bremen 2004 (download)[permanent dead link]; Heinsohn, Gunnar; Steiger, Otto (May 1982). "The Elimination of Medieval Birth Control and the Witch Trials of Modern Times". International Journal of Women's Studies. 3: 193–214. Heinsohn, Gunnar; Steiger, Otto (1999). "Birth Control: The Political-Economic Rationale Behind Jean Bodin's 'Démonomanie'". History of Political Economy. 31 (3): 423–448. doi:10.1215/00182702-31-3-423. PMID 21275210. S2CID 31013297.

- ^ "Fortaleza Declaration: Appropriate Use of Technology for Birth". World Health Organization. 22–26 April 1985. Archived from the original on 2020-02-16. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- ^ Lingo, Alison Klairmont (2004). "Obstetrics and Midwifery § Midwifery from 1900 to the Present". Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood in History and Society. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale. Archived from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2015, from Encyclopedia.com.

Bibliography

- Craven, Christa. 2007 A "Consumer's Right" to Choose a Midwife: Shifting Meanings for Reproductive Rights under Neoliberalism. American Anthropologist, Vol. 109, Issue 4, pp. 701–712. In I.L. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press.

- Ford, Anne R., & Wagner, Vicki. In Bourgeautt, Ivy L., Benoit, Cecilia, and Davis-Floyd, Robbie, ed. 2004 Reconceiving Midwifery. McGill-Queen's University Press: Montreal & Kingston

- MacDonald, Margaret. 2007 At Work in the Field of Birth: Midwifery Narratives of Nature, Tradition, and Home. Vanderbilt University Press: Nashville

- Martin Emily (1991). "The Egg and the Sperm: How Science Has Constructed a Romance Based on Stereotypical Male-Female Roles". Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 16 (3): 485–501. doi:10.1086/494680. S2CID 145638689.

- (in Dutch) Obstetricians in the city of Groningen. Archived 2013-06-25 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

[edit]- Litoff, Judy Barrett. "An historical overview of midwifery in the United States." Pre-and Peri-natal Psychology Journal 1990; 5(1): 5 online Archived 2018-10-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Litoff, Judy Barrett. "Midwives and History." In Rima D. Apple, ed., The History of Women, Health, and Medicine in America: An Encyclopedic Handbook (Garland Publishing, 1990) covers the historiography.

- S. Solagbade Popoola, Ikunle Abiyamo: It is on Bent Knees that I gave Birth 2007 Research material, scientific and historical content based on traditional forms of African Midwifery from Yoruba of West Africa detailed within the Ifa traditional philosophy. Asefin Media Publication

- Greene, M. F. (2012). "Two Hundred Years of Progress in the Practice of Midwifery". New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (18): 1732–1740. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1209764. PMID 23113484. S2CID 19487046.

- Florence Nightingale (1871), Introductory notes on lying-in institutions : Together with a proposal for organising an institution for training midwives and midwifery nurses, London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Tsoucalas G., Karamanou M., Sgantzos M. (2014). "Midwifery in ancient Greece, midwife or gynaecologist-obstetrician?". Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 34 (6): 547. doi:10.3109/01443615.2014.911834. PMID 24832625. S2CID 207435300.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit] Media related to Midwifery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Midwifery at Wikimedia Commons- International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) Archived 2014-08-29 at the Wayback Machine