Marrella

| Marrella Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil of Marrella | |

| |

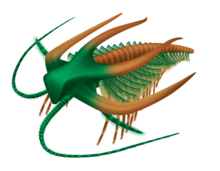

| Life reconstruction of Marrella | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | †Marrellomorpha |

| Order: | †Marrellida |

| Family: | †Marrellidae |

| Genus: | †Marrella Walcott, 1912 |

| Species: | †M. splendens

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Marrella splendens Walcott, 1912

| |

Marrella is an extinct genus of marrellomorph arthropod known from the Middle Cambrian of North America and Asia. It is the most common animal represented in the Burgess Shale of British Columbia, Canada, with tens of thousands of specimens collected. Much rarer remains are also known from deposits in China.

History

[edit]Marrella was the first fossil collected by Charles Doolittle Walcott from the Burgess Shale, in 1909.[1] Walcott described Marrella informally as a "lace crab" and described it more formally as an odd trilobite. It was later reassigned to the now defunct class Trilobitoidea in the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. In 1971, Whittington undertook a thorough redescription of the animal and, on the basis of its legs, gills and head appendages, concluded that it was neither a trilobite, nor a chelicerate, nor a crustacean.[2]

Marrella is one of several unique arthropod-like organisms found in the Burgess Shale. Other examples are Opabinia and Yohoia. The unusual and varied characteristics of these creatures were startling at the time of discovery. The fossils, when described, helped to demonstrate that the soft-bodied Burgess fauna was more complex and diverse than had previously been anticipated.[3]

Morphology

[edit]

Top left– dorsal view on a rendered 3D model

top right and centre right– micrographs under polarized light

top right – well preserved specimen USNM 83486f with the exopods in a "rusty" preservation (cf. García−Bellido and Collins 2006)

bottom left – stereo image of specimen USNM 139665. Exopods of preceding limbs are super−imposing each other, separated by a thin layer of sediment

bottom right – detail of specimen ROM 56766A in "rusty" preservation. Here the spines on the lateral side of the exopod ringlets are well preserved

centre right – one of the smallest specimens of M. splendens USNM 219817e that possesses preserved appendage remains Black bars for centre right image = 0.6mm, rest = 1mm

Specimens of Marrella range from 2.4 to 24.5 millimetres (0.094 to 0.965 in) in length. The head shield had two pairs of long posteriorly curved projections/spines, the posterior pair of which had a serrated keel. There is no evidence of eyes. On the underside of the head was a pair of long and sweeping flexible antennae, composed of about total 30 segments, projecting forward at an angle of 15 to 30 degrees away from the midline. On part of the antennae, the joints between segments bear setae. Behind and slightly above the antennae attached a pair of short and stout paddle-like swimming appendages, composed of one long basal segment and five shorter segments, the edges of the latter of which were fringed with setae.[5][2]

The body had a minimum of 17 segments (tagma), increasing to over 26 segments in larger specimens, each with a pair of branched biramous appendages. The lower branches of each appendage (the endopod) were elongate and leg-like with 5 segments/podomeres excluding the basal segment/basipod, with the terminal segments being tipped with claws. The endopods sequentially decreased in size posteriorly, with the size reduction accelerating beyond the 9th pair. The upper branch (the exopod), which functioned as gill was segmented and bore thin filamentous structures. There is a tiny, button-like telson at the end of the thorax.[5][2]

A 1998 paper suggested that striations present on the front projection of well-preserved specimens of Marrella represented a diffraction grating pattern, that in life would have resulted in an iridescent sheen.[6] However the conclusions of the paper regarding other animals with supposed iridescent diffraction gratings have been questioned by other authors.[7][8] Dark stains are often present at the posterior regions of specimens, probably representing extruded waste matter[9] or hemolymph.[10] A single specimen caught in the act of ecdysis (moulting) is known, which shows that the exoskeleton split at the front of the shield.[11][12]

Ecology

[edit]Marrella is likely to have been an active swimmer that swam close to the seafloor (nektobenthic) with its swimming appendages used in a backstroke motion, with the large spines acting as stabilizers, as well as possibly also having a defensive function. They have been suggested to be filter feeders, with food particles sifted out of the water column by the posterior appendages during swimming before being passed forward by the appendages towards the mouth.[5]

Taxonomy

[edit]Marrella is placed within the Marrellida clade of the Marrellomorpha, a group of arthropods with uncertain affinities known from the Cambrian to Devonian. Within the Marrellida, is it placed as the most basal known member of the group. Cladogram of Marrellida after Moysiuk et al. 2022[13]

| Marrellida |

| |||||||||||||||

Occurrence

[edit]Marrella is the most abundant genus in the Burgess Shale.[14] Most Marrella specimens herald from the 'Marrella bed', a thin horizon, but it is common in most other outcrops of the shale. Over 25,000 specimens have been collected.[15] 5028 specimens of Marrella are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they comprise 9.56% of the community.[16]

A few dozen specimens of an indeterminate species of Marrella have been reported from the Kaili Formation of Yunnan, China, dating to the Wuliuan stage of the Cambrian. A single fragmentary specimen of an indeterminate species is also known from the Balang Formation of Yunnan, China, dating to Cambrian Stage 4. Both deposits are earlier than the Burgess Shale.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (2000). Wonderful Life: Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. Vintage. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-09-927345-5. OCLC 45316756. Also OCLC 44058853.

- ^ a b c Whittington, H. B. (1971). "Redescription of Marrella splendens (Trilobitoidea) from the Burgess Shale, Middle Cambrian, British Columbia" (PDF). Bulletin – Geological Survey of Canada. 209. Geological Survey of Canada: 1–24.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (2000). Wonderful Life: Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. Vintage. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-09-927345-5. OCLC 45316756. Also OCLC 44058853.

- ^ Haug, J. T., Castellani, C., Haug, C., Waloszek, D., Maas, A. (2012). A Marrella−like arthropod from the Cambrian of Australia: a new link between "Orsten"−type and Burgess Shale assemblages. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 58: 629–639. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0120

- ^ a b c García-Bellido, Diego & Collins, Desmond. (2006). A new study of Marrella splendens (Arthropoda, Marrellomorpha) from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale, British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 43. 721-742. 10.1139/e06-012.

- ^ Parker, A. R. (1998). "Colour in Burgess Shale animals and the effect of light on evolution in the Cambrian". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 265 (1400): 967–972. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0385. PMC 1689164.

- ^ Smith, Martin R. (January 2014). Lane, Phil (ed.). "Ontogeny, morphology and taxonomy of the soft-bodied Cambrian 'mollusc' Wiwaxia". Palaeontology. 57 (1): 215–229. Bibcode:2014Palgy..57..215S. doi:10.1111/pala.12063. S2CID 84616434.

The full width of each sclerite [of Wiwaxia] is striated by finely spaced longitudinal lineations. Parker (1998) argued that these were superficial – although they are not visible on surfaces imaged under SEM and do not exhibit interference under transmitted light, so might be better interpreted as internal channels indicating microvillar secretion.

- ^ Parry, Luke; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2019-09-06). "Canadia spinosa and the early evolution of the annelid nervous system". Science Advances. 5 (9): eaax5858. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.5858P. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax5858. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6739095. PMID 31535028.

In Canadia, longitudinal striations along chaetae, which have previously interpreted as external evidence for iridescence, are concordant with the dimensions of microvilli and represent internal rather than external features.

- ^ Whittington, H. B. (1978). "The Lobopod Animal Aysheaia pedunculata Walcott, Middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 284 (1000): 165–197. Bibcode:1978RSPTB.284..165W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1978.0061.

- ^ Pratt, Brian R.; Pushie, M. Jake; Pickering, Ingrid J.; George, Graham N. Synchrotron Imaging of Burgess Shale Fossils: Evidence for Biochemical Copper (Hemocyanin) in the Middle Cambrian Arthropod Marrella splendens. Archived from the original on 2016-03-09.

- ^ Drage, Harriet B.; Legg, David A.; Daley, Allison C. (2023-08-21). "Novel marrellomorph moulting behaviour preserved in the Lower Ordovician Fezouata Shale, Morocco". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 11. doi:10.3389/fevo.2023.1226924. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ García-Bellido, Diego C.; Collins, Desmond H. (May 2004). "Moulting arthropod caught in the act". Nature. 429 (6987): 40. Bibcode:2004Natur.429...40G. doi:10.1038/429040a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15129272.

- ^ Moysiuk, Joseph; Izquierdo-López, Alejandro; Kampouris, George E.; Caron, Jean-Bernard (July 2022). "A new marrellomorph arthropod from southern Ontario: a rare case of soft-tissue preservation on a Late Ordovician open marine shelf". Journal of Paleontology. 96 (4): 859–874. Bibcode:2022JPal...96..859M. doi:10.1017/jpa.2022.11. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ Bottjer, David J.; Etter, Walter; Hagadorn, James W.; Tang, Carol M. (2002). Exceptional Fossil Preservation: A unique view on the evolution of marine life. Columbia University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-231-10255-1. OCLC 47650949.

- ^ García-Bellido, D. C.; Collins, D. H. (2004). "Moulting arthropod caught in the act". Nature. 429 (6987): 40. Bibcode:2004Natur.429...40G. doi:10.1038/429040a. PMID 15129272. S2CID 40015864.

- ^ Caron, Jean-Bernard; Jackson, Donald A. (October 2006). "Taphonomy of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale". PALAIOS. 21 (5): 451–65. Bibcode:2006Palai..21..451C. doi:10.2110/palo.2003.P05-070R. JSTOR 20173022. S2CID 53646959.

- ^ Liu, Qing (May 2013). "The First Discovery of Marrella (Arthropoda, Marrellomorpha) from the Balang Formation (Cambrian Series 2) in Hunan, China". Journal of Paleontology. 87 (3): 391–394. Bibcode:2013JPal...87..391L. doi:10.1666/12-118.1. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 129018525.

External links

[edit]- "Marrella splendens". Burgess Shale Fossil Gallery. Virtual Museum of Canada. 2011. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12.

- "Reconstruction of Marrella from the collections of Charles Doolittle Walcott". Historical Art Gallery. National Museum of Natural History.