Markham, Ontario

Markham | |

|---|---|

| City of Markham | |

| |

| Nickname: The High-Tech Capital | |

| Motto: Leading While Remembering | |

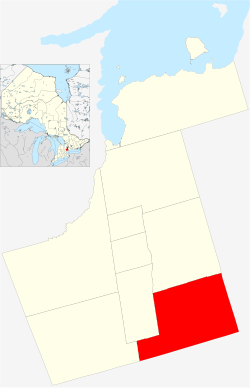

Location of Markham within York Region | |

| Coordinates: 43°52′36″N 79°15′48″W / 43.87667°N 79.26333°W[1] | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| Regional Municipality | York Region |

| Settled | 1794 (Thornhill and Unionville) |

| Incorporated | 1872 (village) 1971 (town) 2012 (city) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Frank Scarpitti |

| • Deputy Mayor | Michael Chan |

| • Governing Body | Markham City Council |

| • MPs | List of MPs |

| • MPPs | List of MPPs |

| Area | |

| • Total | 210.93 km2 (81.44 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 200 m (700 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 338,503 (16th) |

| • Density | 1,604.8/km2 (4,156/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Markhamite |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| Forward Sortation Area | |

| Area codes | 905, 289, 365, and 742 |

| ISO 3166-2 | CA-ON |

| GNBC Code | FDNFZ[1] |

| Website | www |

Markham (/ˈmɑːrkəm/) is a city in York Region, Ontario, Canada. It is approximately 30 km (19 mi) northeast of Downtown Toronto. In the 2021 Census, Markham had a population of 338,503,[2] which ranked it the largest in York Region, fourth largest in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), and 16th largest in Canada.[3]

The city gained its name from the first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, John Graves Simcoe (in office 1791–1796), who named the area after his friend, William Markham, the Archbishop of York from 1776 to 1807.

Indigenous people lived in the area of present-day Markham for thousands of years before Europeans arrived in the area.[4] The first European settlement in Markham occurred when William Berczy, a German artist and developer, led a group of approximately sixty-four German families to North America. While they planned to settle in New York, disputes over finances and land tenure led Berczy to negotiate with Simcoe for 26,000 ha (64,000 acres) in what would later become Markham Township in 1794.[5] Since the 1970s, Markham rapidly shifted from being an agricultural community to an industrialized municipality due to urban sprawl from neighbouring Toronto.[6] Markham changed its status from town to city on July 1, 2012.[7]

As of 2013[update], tertiary industry mainly drives Markham. As of 2010[update], "business services" employed the largest proportion of workers in Markham – nearly 22% of its labour force.[8] The city also has over 1,000[9] technology and life-sciences companies, with IBM as the city's largest employer.[10][11] Several multinational companies have their Canadian headquarters in Markham, including: Honda Canada, Hyundai,[12] Advanced Micro Devices,[13] Johnson & Johnson, General Motors, Avaya,[14] IBM,[15] Motorola,[16] Oracle,[17] Toshiba,[18] Toyota Financial Services,[19] Huawei, Honeywell, General Electric[20] and Scholastic Canada.[21]

History

[edit]

Indigenous people lived in the area of present-day Markham since the end of the last Ice Age and the city is situated on the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), Huron Wendat, Petun and Neutral people.[4][22] In the early 1600s, when explorers from France arrived, they encountered the Huron-Wendat First Nation.[4] The southwest corner of Markham is included in Treaty 13, known as the Toronto Purchase of 1787, which transferred roughly 250,800 acres of land from the Mississauga people to the British Crown for 10 shillings and fishing rights on the Etobicoke river.[4][23] The remainder of Markham's land (roughly east of Woodbine Avenue/Highway 404) is covered by the Johnson-Butler Purchase of 1787-88 (aka Gunshot Treaty) and formally by the Williams Treaties, signed in 1923.[4]

Objects recovered by local mill-owners, the Milne family, in the 1870s give evidence of a village within the boundaries of the present Milne Conservation Area.[22]

European settlement in Markham first began in 1794.[24] The Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, John Graves Simcoe (in office 1791–1796), named the township of Markham, north of the town of York (now Toronto), after his friend William Markham, then Archbishop of York. William Berczy first surveyed Markham as a township in 1793, and in 1794 led 75 German families (including the Ramers, Reesors, Wheters, Burkholders, Bunkers, Wicks and Lewis) from Upstate New York to an area of Markham now known as German Mills.[25] Each family was granted 81 ha (200 acres) of land; however the lack of roads in the region led many to settle in York (present-day Toronto) and Niagara. German Mills later became a ghost town. Between 1803 and 1812 another attempt at settling the region was made. The largest group of settlers were Pennsylvania Dutch, most of them Mennonites. These highly skilled craftsmen and knowledgeable farmers settled the region and founded Reesorville, named after the Mennonite settler Joseph Reesor.[26] In 1825 Reesorville was renamed to Markham and took the name of the unincorporated village (see Markham Village, Ontario).

By 1830, many Irish, Scottish and English families began immigrating to Upper Canada and settling in Markham.[27] Markham's early years blended the rigours of the frontier with the development of agriculture-based industries.[citation needed] The township's many rivers and streams soon supported water-powered saws and gristmills and later wooden mills. With improved transportation routes, such as the construction of Yonge Street in the 1800s, along with the growing population, urbanization increased. In 1842 the township population had reached 5,698; 11,738 ha (29,005 acres) were under cultivation (second highest in the province), and the township had eleven gristmills and twenty-four sawmills.[28]

In 1846 Smith's Canadian Gazetteer indicated a population of about 300, mostly Canadians, Pennsylvanian Dutch (actually Pennsylvania Deitsch or German), other Germans, Americans, Irish and a few from Britain. There were two churches with a third being built. There were tradesmen of various types, a grist mill, an oatmill mill, five stores, a distillery and a threshing-machine maker. There were eleven grist and twenty-four saw mills in the surrounding township.[29] In 1850 the first form of structured municipal government formed in Markham.[30]

By 1857 most of the township had been cleared of timber and was under cultivation. Villages like Thornhill, Unionville and Markham greatly expanded.[31] In 1851 Markham Village "was a considerable village, containing between eight and nine hundred inhabitants, pleasantly situated on the Rouge River. It contains two grist mills ... a woollen factory, oatmeal mill, barley mill and distillery, foundry, two tanneries, brewery, etc., a temperance hall and four churches... ."[32] In 1871, with a township population of 8,152,[33] the Toronto and Nipissing Railway built the first rail line to Markham Village and Unionville, which is still used today by the GO Transit commuter services.

In 1971 Markham was incorporated as a town, as its population skyrocketed due to urban sprawl from Toronto. In 1976 Markham's population was approximately 56,000. Since that time, the population has more than quintupled, with explosive growth in new subdivisions. Much of Markham's farmland has disappeared, but some still remains north of Major Mackenzie Drive. Controversy over the development of the environmentally-sensitive Oak Ridges Moraine will likely[original research?] curb development north of Major Mackenzie Drive and by Rouge National Urban Park east of Reesor Road between Major Mackenzie Drive to Steeles Avenue East to the south.

Since the 1980s Markham has been recognized[by whom?] as a suburb of Toronto. As of 2006[update] the city comprises six major communities: Berczy Village, Cornell, Markham Village, Milliken, Thornhill and Unionville. Many high-tech companies have established head offices in Markham, attracted by the relative abundance of land, low tax-rates and good transportation routes. Broadcom Canada, ATI Technologies (now known as AMD Graphics Product Group), IBM Canada, Motorola Canada, Honeywell Canada and many other well-known companies have chosen Markham as their home in Canada. The city has accordingly started branding itself as Canada's "High-Tech Capital". The province of Ontario has erected a historical plaque in front of the Markham Museum to commemorate the founding of Markham's role[clarification needed] in Ontario's heritage.[34]

Town council voted on May 29, 2012, to change Markham's legal designation from "town" to "city"; according to Councillor Alex Chiu, who introduced the motion, the change of designation merely reflects the fact that many people already think of Markham as a city.[7] Some residents objected to the change because it will involve unknown costs without any demonstrated benefits. The designation officially took effect on July 1.[7]

Geography

[edit]Markham covers 212.47 km2 (82.04 sq mi) and Markham's city centre is at 43°53′N 79°15′W / 43.883°N 79.250°W. It is bounded by five municipalities; in the west is Vaughan with the boundary along Yonge Street between Steeles Avenue and Highway 7 and Richmond Hill with the boundary along Highway 7 from Yonge Street to Highway 404 and at Highway 404 from Highway 7 to 19th Avenue and Stouffville Road. In the south, it borders Toronto with the boundary along Steeles Avenue. In the north it borders Whitchurch–Stouffville with the boundary from Highway 404 to York-Durham Line between 19th Avenue and Stouffville Road. In the east it borders Pickering along York-Durham Line.

Topography

[edit]Markham's average altitude is at 200 m (660 ft) and in general consists of gently rolling hills. The city is intersected by two rivers; the Don River and Rouge River, as well as their tributaries. To the north is the Oak Ridges Moraine, which further elevates the elevation towards the north.

Climate

[edit]Markham borders and shares the same climate as Toronto. On an average day, Markham is generally 1–2 °C (1.8–3.6 °F) cooler than in downtown Toronto. It has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb) and features warm, humid summers with rainfall occurring from May to October and cold, snowy winters. The highest temperature recorded was 37.8 °C (100.0 °F) on August 8, 2001, during the eastern North America heat wave and the lowest temperature recorded was −35.2 °C (−31.4 °F) on January 16, 1994, during the 1994 North American cold wave.[35]

| Climate data for Markham (Buttonville at Toronto Buttonville Airport) WMO ID: 71639; coordinates 43°51′44″N 79°22′12″W / 43.86222°N 79.37000°W; elevation: 198.1 m (650 ft); 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1895–present[a][36] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 16.0 | 18.0 | 29.2 | 35.7 | 41.0 | 46.0 | 50.9 | 47.4 | 44.2 | 38.0 | 25.8 | 20.6 | 50.9 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.9 (58.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

34.6 (94.3) |

36.6 (97.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −1.7 (28.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

4.6 (40.3) |

11.8 (53.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

21.9 (71.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

7.4 (45.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.0 (21.2) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

6.5 (43.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −10.1 (13.8) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

1.2 (34.2) |

7.4 (45.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

2.9 (37.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −35.2 (−31.4) |

−34.4 (−29.9) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

−35.2 (−31.4) |

| Record low wind chill | −42.6 | −41.7 | −35.6 | −18.6 | −7.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −4.2 | −8.8 | −23.9 | −36.6 | −42.6 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 63.5 (2.50) |

51.1 (2.01) |

52.3 (2.06) |

78.9 (3.11) |

80.0 (3.15) |

86.7 (3.41) |

85.2 (3.35) |

71.9 (2.83) |

83.1 (3.27) |

70.6 (2.78) |

76.7 (3.02) |

62.5 (2.46) |

862.4 (33.95) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 27.6 (1.09) |

21.0 (0.83) |

32.8 (1.29) |

71.8 (2.83) |

79.9 (3.15) |

86.7 (3.41) |

85.2 (3.35) |

71.9 (2.83) |

83.1 (3.27) |

70.1 (2.76) |

65.5 (2.58) |

33.4 (1.31) |

728.9 (28.70) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 40.3 (15.9) |

33.9 (13.3) |

19.7 (7.8) |

7.2 (2.8) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.6 (0.2) |

11.7 (4.6) |

32.8 (12.9) |

146.4 (57.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 17.0 | 13.1 | 12.0 | 12.6 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 11.2 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 13.3 | 14.3 | 15.5 | 153.5 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 5.5 | 3.7 | 6.5 | 11.2 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 11.2 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 13.2 | 10.9 | 6.8 | 113.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 14.2 | 11.0 | 7.2 | 2.8 | 0.13 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.42 | 4.8 | 10.6 | 51.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 1500 LST) | 68.3 | 63.5 | 57.7 | 52.9 | 52.8 | 53.9 | 52.9 | 55.2 | 57.6 | 62.1 | 66.8 | 70.4 | 59.5 |

| Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada[35][37] | |||||||||||||

Neighbourhoods

[edit]Markham is made up of many original 19th-century communities, each with a distinctive character. Many of these, despite being technically suburban districts today, are still signed with official "city limits" signs on major roads:

- Almira[38]

- Angus Glen

- Armadale

- Bayview Glen

- Berczy Village

- Box Grove

- Brown's Corners

- Bullock

- Buttonville

- Cachet

- Cashel

- Cathedraltown

- Cedar Grove

- Cedarwood

- Cornell

- Crosby

- Dollar

- Downtown Markham

- Dickson's Hill

- German Mills

- Greensborough

- Hagerman's Corners

- Langstaff

- Legacy

- Locust Hill

- Markham Village

- Middlefield

- Milliken Mills

- Milnesville

- Mongolia

- Mount Joy

- Quantztown

- Raymerville – Markville East

- Rouge Fairways

- Sherwood – Amber Glen

- South Unionville

- Thornhill

- Underwood, Ontario

- Unionville

- Uptown Markham

- Victoria Square

- Vinegar Hill

- Wismer Commons

Thornhill and Unionville are popularly seen as being separate communities. Thornhill straddles the Markham-Vaughan municipal boundary (portions of it in both municipalities). Unionville is a single community with three sub-communities:

- Original Unionville is along Highway 7 and Kennedy Road

- South Unionville is a newer residential community (beginning from the 1990s onwards) south of Highway 7 to Highway 407 and from McCowan to Kennedy Road

- Upper Unionville is a new residential development built on the northeast corner of 16th Avenue and Kennedy Road

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1986 | 114,597 | — |

| 1991 | 153,811 | +34.2% |

| 1996 | 173,383 | +12.7% |

| 2001 | 208,615 | +20.3% |

| 2006 | 261,573 | +25.4% |

| 2011 | 301,709 | +15.3% |

| 2016 | 328,966 | +9.0% |

| 2021 | 338,503 | +2.9% |

| 2021[39], 2016[40], 2011[41], 2006[42], 2001 and 1996 [43], 1991 and 1986[44] | ||

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Markham had a population of 338,503 living in 110,867 of its 114,908 total private dwellings, a change of 2.9% from its 2016 population of 328,966. With a land area of 210.93 km2 (81.44 sq mi), it had a population density of 1,604.8/km2 (4,156.4/sq mi) in 2021.[45]

Immigrants made up 58% of the population of Markham in the 2021 census. Top countries of origin for the immigrant population were China (33.8%, excluding 16.4% from Hong Kong), India (7.2%), Sri Lanka (6.4%), Philippines (3.6%), Iran (3.5%), Pakistan (2.7%), Vietnam (1.8%), Jamaica (1.8%), Guyana (1.6).[46]

Ethnicity

[edit]In the 2021 census, the most reported ethnocultural background was Chinese (47.9%), followed by European (17.7%), South Asian (17.6%), Black (3.1%), West Asian (2.9%), Filipino (2.7%), Korean (1.3%), Arab (1.0%), Latin American (0.8%), and Southeast Asian (0.7%).[47]

The most common ethnic or cultural origins as per the 2021 census are as follows: Chinese (43.3%), Indian (7.0%), Canadian (4.0%), English (3.8%), Hong Konger (3.7%), Sri Lankan (3.3%), Tamil (3.1%), Irish (3.1%), Scottish (3.1%), Filipino (2.9%), Italian (2.8%), Pakistani (2.1%), and Iranian (2.0%).[48]

| Panethnic group |

2021[46] | 2016[49] | 2011[50] | 2006[51] | 2001[52] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |||||

| East Asian[b] | 166,655 | 49.42% | 153,075 | 46.75% | 119,255 | 39.73% | 93,375 | 35.81% | 65,290 | 31.4% | ||||

| European[c] | 59,745 | 17.72% | 71,505 | 21.84% | 82,560 | 27.51% | 89,820 | 34.45% | 92,165 | 44.32% | ||||

| South Asian | 59,485 | 17.64% | 58,270 | 17.8% | 57,375 | 19.12% | 44,995 | 17.26% | 26,360 | 12.68% | ||||

| Middle Eastern[d] | 12,900 | 3.82% | 11,160 | 3.41% | 9,585 | 3.19% | 7,515 | 2.88% | 3,965 | 1.91% | ||||

| Southeast Asian[e] | 11,760 | 3.49% | 11,425 | 3.49% | 11,770 | 3.92% | 9,340 | 3.58% | 6,220 | 2.99% | ||||

| African | 10,435 | 3.09% | 9,655 | 2.95% | 9,715 | 3.24% | 8,005 | 3.07% | 7,860 | 3.78% | ||||

| Latin American | 2,675 | 0.79% | 1,750 | 0.53% | 1,600 | 0.53% | 1,385 | 0.53% | 1,055 | 0.51% | ||||

| Indigenous | 630 | 0.19% | 740 | 0.23% | 485 | 0.16% | 405 | 0% | 290 | 0.14% | ||||

| Other/Multiracial[f] | 12,985 | 3.85% | 9,815 | 3% | 7,800 | 2.6% | 5,920 | 2.27% | 4,730 | 2.27% | ||||

| Total responses | 337,255 | 99.63% | 327,400 | 99.52% | 300,140 | 99.48% | 260,760 | 99.69% | 207,940 | 99.68% | ||||

| Total population | 338,503 | 100% | 328,966 | 100% | 301,709 | 100% | 261,573 | 100% | 208,615 | 100% | ||||

| Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses | ||||||||||||||

Religion

[edit]In 2021, 40.8% of the population did not identify with a particular religion. The most reported religions were Christianity (35.1%), Hinduism (9.2%), Islam (7.9%), Buddhism (4.0%), Judaism (1.4%), and Sikhism (1.1%).[53]

Language

[edit]| Mother tongue[54] | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| English | 114,200 | 34.8 |

| Cantonese | 72,620 | 22.2 |

| Mandarin | 41,790 | 12.7 |

| Tamil | 14,625 | 4.5 |

| Persian | 7,285 | 2.2 |

| Urdu | 6,380 | 1.9 |

| Tagalog (Filipino) | 4,640 | 1.4 |

| Gujarati | 4,510 | 1.4 |

| Punjabi | 3,780 | 1.2 |

| Italian | 3,690 | 1.1 |

| Korean | 3,230 | 1.0 |

| Arabic | 2,720 | 0.8 |

| Greek | 2,455 | 0.7 |

| Hindi | 2,415 | 0.7 |

| Hakka | 2,235 | 0.7 |

| Spanish | 2,085 | 0.6 |

| Min Nan | 2,000 | 0.6 |

| Russian | 1,995 | 0.6 |

| French | 1,880 | 0.6 |

| Chinese (unspecified) | 1,480 | 0.5 |

| Armenian | 1,355 | 0.4 |

| Macedonian | 1,185 | 0.4 |

| Vietnamese | 1,125 | 0.3 |

| Romanian | 945 | 0.3 |

| Wu (Shanghainese) | 940 | 0.3 |

| Knowledge of language[55] | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| English | 294,505 | 90.0 |

| Cantonese | 88,700 | 27.1 |

| Mandarin | 64,350 | 19.7 |

| Tamil | 19,190 | 5.9 |

| French | 19,190 | 5.9 |

| Urdu | 10,175 | 3.1 |

| Hindi | 9,655 | 2.9 |

| Persian | 8,830 | 2.7 |

| Punjabi | 6,615 | 2.0 |

| Tagalog (Filipino) | 6,565 | 2.0 |

| Gujarati | 5,760 | 1.8 |

| Italian | 5,140 | 1.6 |

| Korean | 4,015 | 1.2 |

| Arabic | 3,920 | 1.2 |

| Spanish | 3,825 | 1.2 |

| Greek | 3,705 | 1.1 |

| Hakka | 2,705 | 0.8 |

| Russian | 2,410 | 0.7 |

| Min Nan | 2,295 | 0.7 |

| Vietnamese | 1,950 | 0.6 |

| German | 1,755 | 0.5 |

| Macedonian | 1,720 | 0.5 |

| Armenian | 1,585 | 0.5 |

| Chinese (unspecified) | 1,535 | 0.5 |

| Wu (Shanghainese) | 1,255 | 0.4 |

Government

[edit]City Council

[edit]Markham City Council consists of Frank Scarpitti as mayor, four regional councillors and eight ward councillors each representing one of the city's eight wards. Scarpitti replaced Don Cousens, a former Progressive Conservative MPP for Markham and a Presbyterian church minister. The community elects the mayor and four regional councillors to represent the City of Markham at the regional level. The municipality pays the Councillors for their services, but in many municipalities, members of council usually serve part-time and work at other jobs. Residents elected the current members of council to a four-year term of office, in accordance with standards set by the province. The selection of members for the offices of mayor and regional councillors are made town-wide, while ward councillors are elected by individual ward.

Markham Civic Centre

[edit]

The city council is at the Markham Civic Centre at the intersection of York Regional Road 7 and Warden Avenue. The site of the previous offices on Woodbine Avenue has been redeveloped for commercial uses. The historic town hall on Main Street is now a restored office building. The Mayor's Youth Task Force was created to discuss issues facing young people in the city and to plan and publicize events. Its primary purpose is to encourage youth participation within the community.

Elections

[edit]Municipal elections are held every four years in Ontario. The most recent election took place in October, 2022, and the next is scheduled for October, 2026. The links listed below provide the results of recent election results:

By-laws

[edit]The city is permitted to create and enforce by-laws upon residents on various matters affecting the town. The by-laws are generally enforced by City By-Law enforcement officers, but they may involve York Regional Police if violations are deemed too dangerous for the officers to handle. In addition the by-laws can be linked to various provincial acts and enforced by the town. Violation of by-laws is subject to fines of up to $20,000 CAD. The by-laws of Markham include:

- Animal Control (see Dog Owners' Liability Act of Ontario)

- Construction Permits

- Cannabis

- Driveway Extensions

- Fencing and Swimming Pools

- Heritage Conservation (see Ontario Heritage Act)

- Home-Based Businesses

- Noise

- Parking

- Property Standards

- Registration of Basement Apartments and Second Suites

- Sewers

- Site Alteration

- Waste Collection

- Water Use

| Year | Liberal | Conservative | New Democratic | Green | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 54% | 70,181 | 34% | 43,924 | 8% | 10,171 | 2% | 2,876 | |

| 2019 | 45% | 66,923 | 39% | 58,718 | 7% | 10,526 | 3% | 5,079 | |

| Year | PC | New Democratic | Liberal | Green | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 51% | 49,696 | 9% | 8,354 | 35% | 34,182 | 3% | 3,344 | |

| 2018 | 54% | 68,657 | 20% | 25,531 | 23% | 28,909 | 3% | 3,451 | |

City services

[edit]

Courts and police

[edit]There are no courts in Markham, but the city is served by an Ontario Court of Justice in Newmarket, as well as an Ontario Small Claims court in Richmond Hill. There are also served by a Provincial Offence Court in Richmond Hill. The Ontario Court of Appeal is in Toronto, while the Supreme Court of Canada is in Ottawa, Ontario.

Policing is provided by York Regional Police at a station (5 District) at the corner of McCowan Road and Carlton Road and Highway 7.[58] Highway 404, Highway 407 and parts of Highway 48 are patrolled by the Ontario Provincial Police. Toronto Police Service is responsible for patrol on Steeles from Yonge Street to the York—Durham Line.[citation needed]

Fire

[edit]Markham Fire and Emergency Services was established in 1970 as Markham Fire Department and replaced various local volunteer fire units. Nine fire stations serve Markham. Toronto/Buttonville Municipal Airport is also served by Markham's Fire service.

Hospitals

[edit]Markham Stouffville Hospital in the city's far eastern end is Markham's main healthcare facility, located at the intersection of Highway 7 and 9th Line (407 and Donald Cousens Parkway). Markham is also home to Shouldice Hospital, one of the world's premier facilities for people suffering from hernias. For those living near Steeles, they sometimes will be able to receive treatment at The Scarborough Hospital Birchmount Campus in Toronto/Scarborough. North York General Hospital also serves for 24/7 care, serving North York and the lower Markham area.

Garbage collection

[edit]Garbage collection is provided by Miller Waste Systems since the company's founding in 1961.[59]

Education

[edit]Post-secondary

[edit]

Seneca College has a campus in Markham, at Highway 7 and the 404 near Woodbine Avenue/Leslie Street, in the York Region business district.[60] This location opened in 2005, offering full and part-time programs in business, marketing and tourism, and also the college's departments of Finance, Human Resources and Information Technology Services. Since 2011 the campus has also housed the Confucius Institute.[61] York University's campus in Downtown Markham opened in September 2024. It serves the entirety of York Region and upper Scarborough.[62]

Primary and secondary schools

[edit]Markham has a number of both public and Catholic high schools. All have consistently scored high on standardized tests and have some of the highest rate of graduates attending universities. [citation needed]

The York Region District School Board operates secular English public schools. The York Catholic District School Board operates English Catholic schools. The Conseil scolaire Viamonde operates secular French schools, and the Conseil scolaire catholique MonAvenir operates Catholic French schools.

- York Region District School Board

- Bill Crothers Secondary School

- Bill Hogarth Secondary School

- Bur Oak Secondary School

- Markham District High School

- Markville Secondary School

- Middlefield Collegiate Institute

- Milliken Mills High School

- Pierre Elliott Trudeau High School

- Thornhill Secondary School

- Thornlea Secondary School

- Unionville High School

- York Catholic District School Board

Economy

[edit]

In the 19th century Markham had a vibrant, independent community with mills, distilleries and breweries around the intersection of Highway 7 and Markham Road. The Thomas Speight Wagon Works exported products (wagons, horsecars) around the world, and Markham had a reputation as being more active than York (the former name for Toronto) early on. Most of these industries disappeared leaving farming as the main source of business.

Light industries and businesses began to move into Markham in the 1980s attracted by land and lower taxes. Today, it claims to be "Canada's Hi-Tech Capital" with a number of key companies in the area, such as IBM, Motorola, Toshiba, Honeywell, Apple, Genesis Microchip, and is home to the head office of graphics card producer ATI Technologies (in 2006 merged with AMD). Over 1,100 technology and life science companies have offices in Markham, employing over one fifth of the total workforce.[63] In 2014, the top five employers in the city in order were IBM Canada, the City of Markham, TD Waterhouse Inc., Markham Stouffville Hospital and AMD Technologies Inc.[64]

International Franchise Inc., which owns brands including Swensen's[65] and Yogen Früz[66] and several others, has its headquarters in Markham.[67]

General Motors Canada Canadian Technical Centre has been located in Markham since 2017, in the building which was formerly the Canadian head office of American Express from 1985 to 2015.

Performing arts

[edit]

Markham is home to several locally oriented performing arts groups:

- Kindred Spirits Orchestra

- Markham Little Theatre

- Markham Youth Theatre

- Unionville Theatre Company

- Markham Concert Band

A key arts venue is the 'Markham Theatre For Performing Arts', at the Markham Civic Centre at Highway 7 and Warden Avenue. The facility is owned by the City of Markham and operates under the city's Culture Department.

Culture

[edit]

Until the 1970s, Markham was mostly farmland and marsh, as reflected in events like the Markham Fair. Markham has several theatres, Markham Little Theatre at the Markham Museum,[68] the Markham Youth Theatre, and the Markham Theatre.

The Varley Art Gallery is the city of Markham's art museum. The gallery hosts rotating exhibits, public events, art camps and art classes, among other opportunities for citizens to get involved in the community and learn about local and Canadian art.[69]

The Markham Public Library system has eight branches.[70] Some branches offer unique digital tools such as a Digital Media lab with graphic designs software, a recording studio with video editing / audio editing software and a green screen, and a maker space with 3D printers, virtual reality, and laser cutters.[71] With a library card, user can take free online courses,[72] borrow household tools and equipment[73] and educational toys.[74]

Sports

[edit]Notable sporting events held by Markham include:

Community centres and recreational facilities

[edit]Recreation Department runs programs in these facilities and maintained by the city's Operations Department:

- Aaniin Community Centre – library, indoor pool, multi-purpose rooms

- Angus Glen Community Centre – library, tennis courts, indoor pool

- Armadale Community Centre – multi-purpose rooms, outdoor tennis courts

- Centennial Community Centre – multi-purpose rooms, indoor ice rink, indoor pool, squash courts, gym

- Cornell Community Centre – library, indoor pool, multi-purpose rooms, gym, indoor track, fitness centre

- Crosby Community Centre – indoor ice rink, multi-purpose rooms

- Markham Pan Am Centre – indoor pools, gym, fitness centre

- Markham Village Community Centre – library, indoor ice rink

- Milliken Mills Community Centre – library, indoor pool, multi-purpose rooms, indoor ice rink

- Mount Joy Community Centre – outdoor soccer pitches, indoor ice rink, multi-purpose rooms

- R.J. Clatworthy Community Centre – indoor ice rink, multi-purpose rooms

- Rouge River Community Centre – multi-purpose rooms, outdoor pool

- Thornhill Community Centre – indoor ice rink, multi-purpose rooms, indoor track, library, squash court, gym

Parks and pathways

[edit]Markham has scenic pathways running over 22 km over its region. These pathways include 12 bridges allowing walkers, joggers, and cyclists to make use and enjoy the sights it has to offer. Markham's green space includes woodlots, ravines, and valleys that are not only enjoyable to its residents, but are important for the continued growth of the region's plants and animals. These natural spaces are the habitats for rare plant and insect species, offering food and homes essential for the survival of different native insects and birds.[75]

Parks and pathways are maintained by the city's Operations Department.

Attractions

[edit]

Markham has retained its historic past in part of the town. Here a just few places of interest:

- Frederick Horsman Varley Art Gallery

- Heintzman House – Home of Colonel George Crookshank, Sam Francis and Charles Heintzman of Heintzman & Co., the piano manufacturer.

- Markham Museum

- Markham Village

- Markham Heritage Estates – a unique, specially designed heritage subdivision owned by the City of Markham

- Reesor Farm Market

- Cathedral of the Transfiguration

- Thornhill village

Heritage streets:

- Main Street Markham (Markham Road/Highway 48)

- Main Street Unionville (Kennedy Road/Highway 7)

There are still farms operating in the northern reaches of the town, but there are a few 'theme' farms in other parts of Markham:

- Galten Farms

- Forsythe Family Farms

- Adventure Valley

Markham's heritage railway stations are either an active station or converted to other uses:

- Markham GO Station – built in 1871 by Toronto and Nipissing Railway and last used by CN Rail in the 1990s and restored in 2000 as active GO station and community use

- Locust Hill Station – built in 1936 in Locust Hill, Ontario and last used by the CPR in 1969; relocated in 1983 to the grounds of the Markham Museum; replaced earlier station built in the late 19th century for the Ontario and Quebec Railway and burned down in 1935.

- Unionville Station – built in 1871 by the Toronto and Nipissing Railway, later by Via Rail and by GO Transit from 1982 to 1991; it was sold to the city in 1989 and restored as a community centre within the historic Unionville Main Street area. The building features classic Canadian Railway Style found in Markham and (old) Unionville Stations.

Annual events

[edit]Events taking place annually include the Night It Up! Night Market, Taste of Asia Festival, Tony Roman Memorial Hockey Tournament, Markham Youth Week, Unionville Festival, Markham Village Music Festival, Markham Jazz Festival, Milliken Mills Children's Festival, Markham Ribfest & Music Festival, Doors Open Markham, Thornhill Village Festival, Markham Fair, Olde Tyme Christmas Unionville, Markham Santa Claus Parade and Markham Festival of Lights.

Shopping

[edit]Markham is home to several large malls of 100+ stores. These include:

- CF Markville (160+ stores)

- First Markham Place (180 stores) and Woodside Power Centre

- King Square Shopping Mall (500+ mini-shops)[76]

- Langham Square (700 stores)

- Pacific Mall (450 mini-shops)

There are also a lot of higher-profile malls in nearby Toronto, and elsewhere in York Region.

East Asian businesses

[edit]Many shopping centres in Markham are also ethnically Chinese and East Asian-oriented. This is a reflection of Markham's large East Asian, particularly Chinese Canadian, population making it an important Chinese community in the GTA. They carry a wide variety of traditional Chinese products, apparel, and foods.

On Highway 7, between Woodbine and Warden Avenues, is First Markham Place, containing numerous shops and restaurants; this is several kilometres east of Richmond Hill's Chinese malls. Further east along Highway 7 is an older plaza is at the southwest quadrant with the intersection with Kennedy Road.

Pacific Mall is the most well-known Chinese mall in Markham, at Kennedy Road and Steeles Avenue East, which, combined with neighbouring Market Village (now closed) and Splendid China Mall, formed the second largest Chinese shopping area in North America, after the Golden Village in Richmond, British Columbia.[citation needed] In close proximity, at Steeles Avenue and Warden Avenue, there is the New Century Plaza mall and a half-block away there is a plaza of Chinese shops anchored by a T & T Supermarket.

There are also some smaller shopping centres in Markham, such as:

- Albion Mall

- Alderland Centre

- Denison Centre

- J-Town

- Markham Town Square

- Metro Square

- Peachtree Centre

- New Kennedy Square

- The Shops on Steeles and 404

- Thornhill Square Shopping Centre

Local media

[edit]- Markham Review – local monthly newspaper

- TLM The Local Magazine – local satire & lifestyle magazine[77]

- Markham Economist and Sun – community paper owned by Metroland Media Group York Region site; available online only after print version ceased September 15, 2023

- The Liberal – serving Thornhill and Richmond Hill – community paper owned by Metroland Media Group

- The York Region Business Times – business news

- York Region Media Group – Online news which includes some Metroland Media papers

- North of the City – magazine for York Region

- Rogers Cable 10 – community TV station for York Region, owned by Rogers Media

- Markham News24' – Hyper-local, video-based news website focusing on municipal politics, crime, lifestyle and business features

- Sing Tao Daily – an ethnic Chinese newspaper that serves the Greater Toronto Area

Transportation

[edit]Roads

[edit]Road network

[edit]Markham's road network is based on the concession system. In 1801, Markham was divided into 10 concessions, with a north–south road separating each one. The concessions were further divided by a number of east–west sideroads. This formed a grid plan road network, with an intersection occurring approximately every two kilometers. Even though some of these roads have been realigned, Markham's present road network for the most part still follows the original grid plan.

Markham's concession (north–south) arterial roads are listed below, ordered from west to east (former numbers in parentheses):

Yonge Street

Yonge Street

- Boundary with the City of Vaughan

Bayview Avenue

Bayview Avenue Leslie Street

Leslie Street Woodbine Avenue

Woodbine Avenue Warden Avenue (5th Concession Road)

Warden Avenue (5th Concession Road) Kennedy Road (6th Concession Road)

Kennedy Road (6th Concession Road) McCowan Road (7th Concession Road)

McCowan Road (7th Concession Road) Markham Road (8th Concession Road)

Markham Road (8th Concession Road)

- Continues as

Highway 48 north of Major Mackenzie Drive

Highway 48 north of Major Mackenzie Drive

- Continues as

Ninth Line (9th Concession Road)

Ninth Line (9th Concession Road) Donald Cousens Parkway / Markham By-pass

Donald Cousens Parkway / Markham By-pass

- Signed as a regular road south of Box Grove By-pass

- Reesor Road (10th Concession Road)

- Eleventh Line (11th Concession Road)

York-Durham Line

York-Durham Line

- Boundary with the City of Pickering

Reesor Road and Eleventh Line are the only north–south roads that are not fully regional roads. These two roads are rural routes with very few homes and minimal traffic. Eleventh Line ends just south of Highway 407 with the road rerouted (old section fenced off with partial gravel bed) to intersect with York-Durham Line. Areas east of Donald Cousens Boulevard either serve new residential developments or are largely rural and/or agricultural.

Markham's sideroad (east–west) arterials are listed below, ordered from south to north (former numbers in parentheses):

- Steeles Avenue

- Original Scarborough Townline, boundary with the City of Toronto

14th Avenue

14th Avenue

- Continues west of

Warden Avenue as Alden Road

Warden Avenue as Alden Road

- Continues west of Rodick Road as Esna Park Drive

- Continues west of

Woodbine Avenue as John Street

Woodbine Avenue as John Street

- Continues west of

- Continues west of Rodick Road as Esna Park Drive

- Continues west of

Regional Road 7 (formerly 15th Avenue)

Regional Road 7 (formerly 15th Avenue)

- Continues as

Highway 7 east of Reesor Road

Highway 7 east of Reesor Road

- Continues as

16th Avenue

16th Avenue Major Mackenzie Drive East (17th Avenue)

Major Mackenzie Drive East (17th Avenue) Elgin Mills Road East (18th Avenue)

Elgin Mills Road East (18th Avenue)

- Signed as a standard road east of Victoria Square Boulevard

- 19th Avenue

- Boundary with the Town of Whitchurch-Stouffville

Important thoroughfares

[edit]Major highways that pass through Markham include King's Highway 404 (from Toronto to just south of Lake Simcoe), which marks Markham's boundary with the City of Richmond Hill, and the 407 ETR (more commonly known as Highway 407), a privately owned toll highway that passes north of Toronto and connects Markham with Burlington and Oshawa. Highway 404 is one of the most important routes used for travel to and from the City of Toronto. Highway 407 primarily serves Markham from Yonge Street to York-Durham Line. The highway connects Markham with Clarington to the east, and Burlington to the west.

One of the most heavily travelled arterial roads in Markham is Regional Road 7, a major east–west artery. This road is more commonly referred to as Highway 7, a name which comes from the time when it used to be a provincial highway. The road is still officially Highway 7 east of Reesor Road. Other major east–west routes include 16th Avenue, Major MacKenzie Drive, the combination of John Street/Esna Park Drive/14th Avenue, and Steeles Avenue which forms Markham's southern boundary with Toronto.

Rail

[edit]

The GO Transit Stouffville line, a commuter rail line stretching from Lincolnville to downtown Toronto, provides passenger rail service in Markham. It operates only at rush hour and uses tracks owned by Metrolinx, the provincial transit agency. Five stations on the Stouffville line serve Markham, of which 4 are within the municipal borders. In 2015, Metrolinx announced that the Stouffville Line would get an expansion in service, bringing all day both directional trains from Union Station to Unionville GO Station.[78] Markham's section of this GO line also came under the spotlight in 2015 as City of Toronto Mayor John Tory's announced SMART Track plan for rapid transit expansion in Toronto includes the rail spur between Union Station and the Unionville GO.[79]

On April 8, 2019, GO Transit added ten midday train trips to Mount Joy GO Station, replacing the need for passengers to change to buses at Unionville GO.[80]

Public transit

[edit]

York Region Transit (YRT) connects Markham with surrounding municipalities in York Region, and was created in 2001 from the merger of Markham Transit, Richmond Hill Transit, Newmarket Transit and Vaughan Transit. YRT to connects to the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) subway system by way of Viva bus rapid transit from Finch station along Yonge Street, and Don Mills station through Unionville and on to Markville Mall.

YRT has two major terminals in Markham: Unionville GO Terminal and the new Cornell Terminal, replacing Markham Stouffville Hospital Bus Terminal.

The TTC also provides service in Markham on several north–south routes, such as Warden Avenue, Birchmount Road, McCowan Road and Markham Road. These routes charge riders a double fare if they are travelling across the Steeles border.

GO Transit provides train service on the old trackbed of the Toronto and Nipissing Railway, which connects Markham with downtown Toronto on the Stouffville commuter rail service. The line has stops at several stations in Markham, namely Unionville GO Station, Centennial GO Station, Markham GO Station, and Mount Joy GO Station. The Richmond Hill commuter rail line provides service to the Langstaff GO Station, which straddles Markham and Richmond Hill but is used primarily by residents of west-central Markham and southern Richmond Hill.

Air

[edit]Toronto/Buttonville Municipal Airport, Canada's 11th busiest airport (Ontario's 4th busiest).[81] The airport permits general aviation and business commuter traffic to Ottawa and Montreal, Quebec. The airport is slated to close for development, but it has been delayed until at least 2023.

Markham Airport or Toronto/Markham Airport, (TC LID: CNU8), is a private airport operating 2.6 nautical miles (4.8 kilometres; 3.0 miles) north of Markham, north of Elgin Mills Road. The airport is owned and operated by Markham Airport Inc. and owned by a numbered Ontario company owned by the Thomson family of Toronto. The airport is not part of the Greater Toronto Airports Authority (GTAA). The airport has a 2,013 ft (614 m) runway for small and private aircraft only (with night flying capabilities). The Royal Canadian Air Cadets Gliding Program formerly used the airport for glider operations in the spring and fall.

Notable people

[edit]Partner Cities

[edit]Cultural collaboration cities

[edit]- Eabametoong First Nation, Kenora District, Ontario, Canada (January 1, 2017)[82]

Sister cities

[edit]Source:[83]

- Nördlingen, Bavaria, Germany (October 2001)

- Cary, North Carolina, United States (April 2002)

- Wuhan, Hubei, China (October 7, 2003)

Friendship cities

[edit]- Huadu, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China (1998)

- Xiamen, Fujian, China (July 22, 2012)

- Zhongshan, Guangdong, China (September 30, 2012)

- Zibo, Shandong, China (November 24, 2012)

- Foshan, Guangdong, China (December 3, 2012)

- Ganzhou, Jiangxi, China (September 20, 2013)

- Qingdao, Shandong, China (October 7, 2013)

- Meizhou, Guangdong, China (December 10, 2013)

- Jiangmen, Guangdong, China (April 23, 2014)

- Nanhai, Guangdong, China (June 13, 2014)

- Mullaitivu, Northern Province, Sri Lanka (January 14, 2017)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Long term records have been recorded at various climate stations in or nearby Markham since 1895. From 1895 to 1908 at Toronto Agincourt, 1908 to 1918 at Aurora, 1918 to 1959 at Oak Ridges, 1959 to 1986 at Richmond Hill and 1986 to present at Toronto Buttonville Airport

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Chinese", "Korean", and "Japanese" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes all persons that did not make up part of a visible minority or an indigenous identity.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "West Asian" and "Arab" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Filipino" and "Southeast Asian" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Visible minority, n.i.e." and "Multiple visible minorities" under visible minority section on census.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Markham". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ a b c "Markham, City Ontario (Census Subdivision)". Census Profile, Canada 2021 Census. Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Archived from the original on February 12, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Tuckey, Bryan (July 24, 2015). "Why Markham is the next highrise community". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Markham | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "A history of the town of Markham". City of Markham. The Corporation of the City of Markham. 2012. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

In May 1794, Berczy negotiated with Simcoe for 64,000 acres in Markham Township, soon to be known as the German Company Lands. The Berczy settlers, joined by several Pennsylvania German families, set out for Upper Canada. Sixty-four families arrived that year [...]

- ^ "A history of the town of Markham". City of Markham. The Corporation of the City of Markham. 2012. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Markham to change from town to city" . CBC News, May 30, 2012.

- ^ "Labour Force Profile" (PDF). Economic Profile Year End 2010. Town of Markham Economic Development Department. 2010. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Markham Quick Facts – 2016".

- ^ "Why is Markham Canadaès High-Tech Capital?". Town of Markham. The Corporation of the Town of Markham. 2011. Archived from the original on December 18, 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Top 10 Employers in Markham" (PDF). Town of Markham. April 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Help Centre". Hyundai Auto Canada Corp. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ "AMD Locations". AMD. Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. 2011. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Connect with Avaya". Avaya. Avaya Inc. 2011. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "IBM: Helping Canada and the World Work Better". About IBM. IBM. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Office Locations". About Us. Motorola Solutions, Inc. 2011. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us – Oracle Canada". www.oracle.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Contact Us". Support. Toshiba Canada. 2011. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Toyota Canada – Cars, Pickup Trucks, SUVs, Hybrids and Crossovers". Toyota Canada. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ "Canadian Regional Sales Offices". www.gegridsolutions.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Scholastic Canada". Scholastic Canada. Archived from the original on March 9, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ a b City of Markham (2014). "Aboriginal Presence in the Rouge Valley". City of Markham Tourism. Archived from the original on March 13, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ "Fact Sheet - The Brant tract and the Toronto Purchase specific claims". April 15, 2013. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "Markham History". The City of Markham Official Website. July 22, 2023.

- ^ For a complete history, cf. Isabel Champion, ed., Markham: 1793–1900[permanent dead link] (Markham, ON: Markham Historical Society, 1979).

- ^ See I. Champion, Markham: 1793–1900 Archived 2012-09-08 at archive.today (Markham, ON: Markham Historical Society, 1979), p. 248; also Markham Village – A Brief History 1800–1919 Archived 2011-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, Markham Public Library (website).

- ^ For a complete history of Markham's early years, cf. Isabel Champion, ed., Markham: 1793–1900[permanent dead link] "Markham: 1793–1900". Retrieved January 18, 2018.[permanent dead link] (Markham, ON: Markham Historical Society, 1979).

- ^ Markham, Canadian Gazetteer (Toronto: Roswell, 1849), 111.

- ^ Smith, Wm. H. (1846). Smith's Canadian Gazetteer – Statistical and General Information Respecting All Parts of the Upper Province, or Canada West. Toronto: H. & W. ROWSELL. p. 111.

- ^ Cf. C.P. Mulvany et al., The Township of Markham, History of Toronto and County of York, Ontario (Toronto: C.B. Robinson, 1885), 114ff.

- ^ Cf. the detailed 1878 map, Township of Markham Archived 2020-08-17 at the Wayback Machine, Illustrated historical atlas of the county of York and the township of West Gwillimbury & town of Bradford in the county of Simcoe, Ont. (Toronto : Miles & Co., 1878).

- ^ C.P. Mulvany, et al., "The Village of Markham," History of Toronto and County of York, Ontario (Toronto: C.B. Robinson, 1885), p. 198.

- ^ C.P. Mulvany, et al., "The Township of Markham," History of Toronto and County of York, Ontario (Toronto: C.B. Robinson, 1885), p. 121.

- ^ "Ontario Plaque". Ontarioplaques.com. September 22, 2009. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "Toronto Buttonville Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981−2010. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ "Technical Information and Metadata". Daily climate records (LTCE). Environment Canada. Retrieved October 15, 2024.

- ^ "Long Term Climate Extremes for Markham Area (Virtual Station ID: VSON85V)". Daily climate records (LTCE). Environment Canada. Retrieved October 15, 2024.

- ^ Cf. Isabel Champion, ed., Markham: 1793–1900 Archived 2012-11-04 at the Wayback Machine (Markham, ON: Markham Historical Society, 1979), pp. 225; 121f.; 148; 227; 338. See also articles on Almira from the Stouffville Tribune Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "2021 Community Profiles". 2021 Canadian census. Statistics Canada. February 4, 2022.

- ^ "2016 Community Profiles". 2016 Canadian census. Statistics Canada. August 12, 2021.

- ^ "2011 Community Profiles". 2011 Canadian census. Statistics Canada. March 21, 2019.

- ^ "2006 Community Profiles". 2006 Canadian census. Statistics Canada. August 20, 2019.

- ^ "2001 Community Profiles". 2001 Canadian census. Statistics Canada. July 18, 2021.

- ^ "1991 Census Highlights" (PDF). The Daily. Statistics Canada. April 28, 1992. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 24, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions (municipalities), Ontario". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Markham, City (CY) [Census subdivision], Ontario". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022.

- ^ "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Markham, City (CY) [Census subdivision], Ontario". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 27, 2021). "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (November 27, 2015). "NHS Profile". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (August 20, 2019). "2006 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (July 2, 2019). "2001 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Markham, City (CY) [Census subdivision], Ontario". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census - Language". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census - Language". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Official Voting Results Raw Data (poll by poll results in Markham)". Elections Canada. April 7, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Official Voting Results by polling station (poll by poll results in Markham)". Election Ontario. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "#5 District – Markham Archived 2018-09-19 at the Wayback Machine." York Regional Police. Retrieved on September 19, 2018. "8700 McCowan Road Markham, ON L3P 3M2"

- ^ "Corporate Profile". Miller Waste. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ "Markham Campus". Seneca College. May 23, 2018. Archived from the original on October 25, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ "Confucius Institute at Seneca Opening Ceremony – Seneca – Toronto, Ontario, Canada". Senecacollege.ca. Archived from the original on October 25, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ Al-Shibeeb, Dina (July 24, 2020). "'Historic': $275.5M York University Markham Centre Campus announced". Yorkregion.com. Metroland Media Group Ltd. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "Statistics and Demographics". City of Markham. 2014. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015.

- ^ "Top 100 Employers in Markham, 2014" (PDF). City of Markham. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 14, 2015.

- ^ "Contact Us". Swensen's Ice Cream. Swensen's. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived July 10, 2019, at the Wayback Machine." Yogen Früz. Retrieved on March 15, 2014. "Yogen Früz headquarters 210 Shields Court; Markham, Ontario L3R 8V2, Canada"

- ^ "About Us". International Franchise Inc. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ "Markham Museum Facilities" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 21, 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ "Varley Art Gallery About US". City of Markham. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "Branches and Hours". Markham Public Library. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "Maker Space". Markham Public Library. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "Important Update about Lynda.com". City of Markham. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "Region's First Lendery is Now Open at Markham Public Library". York Region News. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "Markham libraries extend hours". Markham Review. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "City of Markham – Trees, Parks & Pathways". www.markham.ca. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ "King Square". Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ "The Local Magazine – News, Views and Opinions". www.thelocalmagazine.com. Archived from the original on December 27, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ Kalinowski, Tess (August 7, 2015). "The new train service is expected to be in the off-peak hours". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Kalinowski, Tess (April 16, 2015). "Kitchener and Stouffville GO lines are on track for electrification needed to boost service frequencies". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ "New GO Train Service | GO Transit". www.gotransit.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ "Total aircraft movements by class of operation — NAV CANADA towers". Statcan.gc.ca. March 12, 2010. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ "The City of Markham and Eabametoong First Nation Sign Partnership Accord". Indigenous Business & Finance Today. February 1, 2017. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ "Sister Cities & International Partners". City of Markham. Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- "Markham, Ontario (Code 3519036) Census Profile". 2011 census. Government of Canada - Statistics Canada. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- "Markham, Ontario (Code 3519036) Census Profile". 2016 census. Government of Canada - Statistics Canada. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Official website

Markham travel guide from Wikivoyage

Markham travel guide from Wikivoyage