March (territory)

In medieval Europe, a march or mark was, in broad terms, any kind of borderland,[1] as opposed to a state's "heartland". More specifically, a march was a border between realms or a neutral buffer zone under joint control of two states in which different laws might apply. In both of these senses, marches served a political purpose, such as providing warning of military incursions or regulating cross-border trade.

Marches gave rise to the titles marquess (masculine) or marchioness (feminine).

Etymology

[edit]The word "march" derives ultimately from a Proto-Indo-European root *mereg-, meaning "edge, boundary". The root *mereg- produced Latin margo ("margin"), Old Irish mruig ("borderland"), Welsh bro ("region, border, valley") and Persian and Armenian marz ("borderland"). The Proto-Germanic *marko gave rise to the Old English word mearc and Frankish marka, as well as Old Norse mǫrk meaning "borderland, forest",[2] and derived from merki "boundary, sign",[2] denoting a borderland between two centres of power.

In Old English, "mark" meant "boundary" or "sign of a boundary", and the meaning only later evolved to encompass "sign" in general, "impression" and "trace".

The Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia took its name from West Saxon mearc "marches", which in this instance referred explicitly to the territory's position on the Anglo-Saxon frontier with the Romano-British to the west.

During the Frankish Carolingian dynasty, usage of the word spread throughout Europe.

The name "Denmark" preserves the Old Norse cognates merki ("boundary") mǫrk ("wood", "forest") up to the present. Following the Anschluss, the Nazi German government revived the old name "Ostmark" for Austria.

Historical examples of marches and marks

[edit]Frankish Empire and successor states

[edit]Marca Hispanica

[edit]In the early ninth century, Charlemagne issued his new kind of land grant, the aprisio, which redisposed land belonging to the Imperial fisc in deserted areas, and included special rights and immunities that resulted in a range of independence of action.[3] Historians interpret the aprisio both as the basis of feudalism and in economic and military terms as a mechanism to entice settlers to a depopulated border region. Such self-sufficient landholders would aid the counts in providing armed men in defense of the Frankish frontier. Aprisio grants (the first ones were in Septimania) emanated directly from the Carolingian king, and they reinforced central loyalties, to counterbalance the local power exercised by powerful marcher counts.[citation needed]

After some early setbacks, Emperor Louis the Pious ventured beyond the province of Septimania and eventually took Barcelona from the Moorish emir in 801. Thus he established a foothold in the borderland between the Franks and the Moors. The Carolingian "Hispanic Marches" (Marca Hispanica) became a buffer zone ruled by a number of feudal lords, among them the count of Barcelona. It had its own outlying territories, each ruled by a lesser miles with armed retainers, who theoretically owed allegiance through a count to the emperor or, with less fealty, to his Carolingian and Ottonian successors. Such territory had a catlá ("castellan" or lord of the castle) in an area largely defined by a day's ride, and the region became known, like Castile at a later date, as "Catalunya". [citation needed] Counties in the Pyrenees that appeared in the 9th century, in addition to the County of Barcelona, included Cerdanya, Girona and Urgell.

Communications were arduous, and the power centre was far away. Primitive feudal entities developed, self-sufficient and agrarian, each ruled by a small hereditary military elite. The sequence in the County of Barcelona exhibits a pattern that emerges similarly in marches everywhere: the count is appointed by the king (from 802), the appointment settles on the heirs of a strong count (Sunifred) and the appointment becomes a formality, until the position is declared hereditary (897) and then the count declares independence (by Borrell II in 985). At each stage the de facto situation precedes the de jure assertion, which merely regularizes an existing fact of life. This is feudalism in the larger landscape.[citation needed]

Some counts aspired to the characteristically Frankish (Germanic) title "Margrave of the Hispanic March", a "margrave" being a graf ("count") of the march.[citation needed]

The early history of Andorra provides a fairly typical career of another such march county, the only modern survivor in the Pyrenees of the Hispanic Marches.[citation needed]

Marches set up by Charlemagne

[edit]- The Danish March (sometimes regarded as just a series of forts rather than a march) between the Eider and Schlei rivers, against the Danes;

- the Saxon or Nordalbingen march between the Eider and Elbe rivers in modern Holstein, against the Obotrites;

- the Thuringian or Sorbian march on the Saale river, against the Sorbs dwelling behind the limes sorabicus;

- the March of Lusatia, March of Meissen, March of Merseburg and March of Zeitz;

- the Franconian march in modern Upper Franconia, against the Czechs;

- the Avar march between Enns river and Wienerwald (the later Eastern March that became the Margraviate of Austria);

- the Pannonian march east of Vienna (divided into Upper and Lower);

- the Carantanian march;

- Steiermark (Styria), established under Charlemagne from a part of Carantania (Carinthia), erected as a border territory against the Avars and Slavs;

- the March of Friuli;

- the Marca Hispanica against the Muslims of Al-Andalus

France

[edit]The province of France called Marche (Occitan: la Marcha), sometimes Marche Limousine, was originally a small border district between the Duchy of Aquitaine and the domains of the Frankish kings in central France, partly of Limousin and partly of Poitou.[4]

Its area was increased during the 13th century and remained the same until the French Revolution. Marche was bounded on the north by Berry, on the east by Bourbonnais and Auvergne; on the south by Limousin itself and on the west by Poitou. It embraced the greater part of the modern département of Creuse, a considerable part of the northern Haute-Vienne, and a fragment of Indre, up to Saint-Benoît-du-Sault. Its area was about 1,900 square miles (4,900 km2) its capital was Charroux and later Guéret, and among its other principal towns were Dorat, Bellac and Confolens.[5]

Marche first appeared as a separate fief about the middle of the 10th century when William III, duke of Aquitaine, gave it to one of his vassals named Boso, who took the title of count. In the 12th century it passed to the family of Lusignan, sometimes also counts of Angoulême, until the death of the childless Count Hugh in 1303, when it was seized by King Philip IV. In 1316 it was made an appanage for his youngest son Charles and a few years later (1327) it passed into the hands of the family of Bourbon.[5]

The family of Armagnac held it from 1435 to 1477, when it reverted to the Bourbons, and in 1527 it was seized by King Francis I and became part of the domains of the French crown. It was divided into Haute-Marche (i.e. "Upper Marche") and Basse-Marche (i.e. "Lower Marche"), the estates of the former being in existence until the 17th century. From 1470 until the Revolution the province was under the jurisdiction of the parlement of Paris.[5]

Several communes of France are named similarly:

- Marches, Drôme in the Drôme département

- La Marche in the Nièvre département

Germany and Austria

[edit]The Germanic tribes that Romans called Marcomanni, who battled the Romans in the 1st and 2nd centuries, were simply the "men of the borderlands".

Marches were territorial organisations created as borderlands in the Carolingian Empire and had a long career as purely conventional designations under the Holy Roman Empire. In modern German, "Mark" denotes a piece of land that historically was a borderland, as in the following names:

Later medieval marches

[edit]- Nordmark, the "Northern March", the Ottonian empire's territorial organisation on the conquered areas of the Wends. In 1134, in the wake of a German crusade against the Wends, the German magnate Albert the Bear was granted the Northern March by the Holy Roman Emperor Lothar II.

- the March of the Billungs on the Baltic coast, stretching approximately from Stettin (Szczecin) to Schleswig;

- Marca Geronis (march of Gero), a precursor of the Saxon Eastern March, later divided into smaller marches (the Northern March, which later was reestablished as Margraviate of Brandenburg; the Lusatian March and the Meißen March in modern Free state of Saxony; the March of Zeitz; the Merseburg March; the Milzener March around Bautzen);

- March of Austria (marcha Orientalis, the "Eastern March" or "Bavarian Eastern March" (German: Ostmark) in modern lower Austria);

- the Hungarian March

- the Carantania march or March of Styria (Steiermark);

- the Drau March (Marburg and Pettau);

- the Sann March (Cilli);

- the Krain or March of Carniola, also Windic march and White Carniola (White March), in modern Slovenia.

- three marches were created in the Low Countries: Antwerp, Valenciennes, Ename.

Other

[edit]- The Margraviate of Brandenburg, its ruler designated Markgraf (margrave, literally "march-count"). It was further divided into regions also designated "Mark":

- Altmark ("Old March"), the western region of the former margraviate, between Hamburg and Magdeburg.

- Mittelmark ("Central March"), the area surrounding Berlin. Today, this region makes up for the bulk of the German federal state of Brandenburg, and thus in modern usage is referred to as Mark Brandenburg.

- Neumark ("New March") since the 1250s was Brandenburg's eastern extremity between Pomerania and Greater Poland. Since 1945, the area is a part of Poland.

- Uckermark, the Brandenburg–Pomeranian borderland. The name is still in use for the region as well as for a Brandenburgian district.

- Mark, a medieval territory that is recalled in the Märkischer Kreis district (formed in 1975) of today's North Rhine-Westphalia. The northern portion (north of the Lippe River) is still called Hohe Mark ("Higher Mark"). The former "Lower Mark" (between Ruhr and Lippe rivers) is the present Ruhr area and is no longer called "Mark". The title, in the form "Count of the Mark", survived the territory as a subsidiary title of the Dukes of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

- Ostmark ("Eastern March") is a modern rendition of the term marchia orientalis used in Carolingian documents referring to the area of Lower Austria that was later a markgraftum (margraviate or "county of the mark"). Ostmark has been variously used to denote Austria, the Saxon Eastern March, or, as Ostmarkenverein, the territories Prussia gained in the partitions of Poland.

Habsburg Empire

[edit]

Italy

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

From the Carolingian period onwards the name marca begins to appear in Italy, first the Marca Fermana for the mountainous part of Picenum, the Marca Camerinese for the district farther north, including a part of Umbria, and the Marca Anconitana for the former Pentapolis (Ancona). In 1080, the marca Anconitana was given in investiture to Robert Guiscard by Pope Gregory VII, to whom the Countess Matilda ceded the marches of Camerino and Fermo.

In 1105, the Emperor Henry IV invested Werner with the whole territory of the three marches, under the name of the March of Ancona. It was afterwards once more recovered by the Church and governed by papal legates as part of the Papal States. The Marche became part of the Kingdom of Italy in 1860. After Italian unification in the 1860s, Austria-Hungary still controlled territory Italian nationalists still claimed as part of Italy. One of these territories was Austrian Littoral, which Italian nationalists began to call the Julian March because of its positioning and as an act of defiance against the hated Austro-Hungarian empire.

Marche were repeated on a miniature level, fringing many of the small territorial states of pre-Risorgimento Italy with a ring of smaller dependencies on their borders, which represent territorial marche on a small scale. A map of the Duchy of Mantua in 1702 (Braudel 1984, fig 26) reveals the independent, though socially and economically dependent arc of small territories from the principality of Castiglione in the northwest across the south to the duchy of Mirandola southeast of Mantua: the lords of Bozolo, Sabioneta, Dosolo, Guastalla, the count of Novellare.

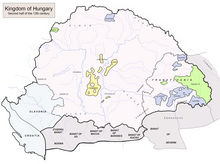

Hungary

[edit]

In medieval Hungary the system of gyepű and gyepűelve, effective until the mid-13th century, can be considered as marches even though in its organisation it shows major differences from Western European feudal marches. For one thing, the gyepű was not controlled by a Marquess.

The Gyepű was a strip of land that was specially fortified or made impassable, while gyepűelve was the mostly uninhabited or sparsely inhabited land beyond it. The gyepűelve is much more comparable to modern buffer zones than traditional European marches.

Portions of the gyepű were usually guarded by tribes who had joined the Hungarian nation and were granted special rights for their services at the borders, such as the Székelys, Pechenegs and Cumans. A ban on settlement north of Niš by the Byzantine Empire in the twelfth century helped to establish uninhabited marchland between the empire's territory and Hungary.[6]

The Hungarian gyepű originates from the Turkish yapi meaning palisade. During the 17th and 18th centuries these borderlands were called Markland in the area of Transylvania that bordered with the Kingdom of Hungary and was controlled by a Count or Countess.[7]

Iberia

[edit]In addition to the Carolingian Marca Hispanica, Iberia was home to several marches set up by the native states. The future kingdoms of Portugal and Castile were founded as marcher counties intended to protect the Kingdom of León from the Cordoban Emirate, to the south and east respectively.

Likewise, Córdoba set up its own marches as a buffer to the Christian states to the north. The Upper March (al-Tagr al-A'la), centered on Zaragoza, faced the eastern Marca Hispanica and the western Pyrenees, and included the Distant or Farthest March (al-Tagr al-Aqsa). The Middle March (al-Tagr al-Awsat), centred on Toledo and later Medinaceli, faced the western Pyrenees and Asturias. The Lower March (al-Tagr al-Adna), centred on Mérida and later Badajoz, facing León and Portugal. These too would give rise to Kingdoms, the Taifas of Zaragoza, Toledo, and Badajoz.

Scandinavia

[edit]Denmark means "the march of the Danes".

In Norse, "mark" meant "borderlands" and "forest"; in present-day Norwegian and Swedish it has acquired the meaning "ground", while in Danish it has come to mean "field" or "grassland".

Markland was the Norse name of an area in North America discovered by Norwegian Vikings.

The forests surrounding Norwegian cities are called "Marka" – the marches. For example, the forests surrounding Oslo are called Nordmarka, Østmarka and Vestmarka – i.e. the northern, eastern and western marches.

In Norway, there are – or have been – the counties:

- Finnmark, "the borderlands of the Sámi" (known to the Norse as Finns)

- Hedmark, "the borderlands of heath"

- Telemark, "the borderlands of the Þela tribe"[8]

In Finland, mark occurs in the following placenames in Satakunta:

- Noormarkku (Swedish: Norrmark), a former municipality of Finland

- Pomarkku (Swedish: Påmark), a municipality of Finland

- Söörmarkku (Swedish: Södermark), a village in Noormarkku, Finland

In Värmland in Sweden, Nordmark Hundred was the frontier area near the border to Norway. Almost all of it is now a part of Årjäng Municipality. In the Middle Ages the area was called Nordmarkerna and was a part of Dalsland and not of Värmland.

British Isles

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

The name of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the midlands of England was Mercia. The name "Mercia" comes from the Old English for "boundary folk", and the traditional interpretation was that the kingdom originated along the frontier between the Welsh and the Anglo-Saxon invaders, although P. Hunter Blair has argued an alternative interpretation that they emerged along the frontier between the Kingdom of Northumbria and the inhabitants of the River Trent valley.

Latinizing the Anglo-Saxon term mearc, the border areas between England and Wales were collectively known as the Welsh Marches (marchia Wallia), while the native Welsh lands to the west were considered Wales Proper (pura Wallia). The Norman lords in the Welsh Marches were to become the new Marcher Lords.

The title Earl of March is at least two distinct feudal titles: one in the northern marches, as an alternative title for the Earl of Dunbar (c. 1290 in the Peerage of Scotland); and one, that was held by the family of Mortimer (1328 in the Peerage of England), in the west Welsh Marches.

The Scottish Marches is a term for the border regions on both sides of the border between England and Scotland. From the Norman conquest of England until the reign of King James VI of Scotland, who also became King James I of England, border clashes were common and the monarchs of both countries relied on Marcher Lords to defend the frontier areas known as the Marches. They were hand-picked for their suitability for the challenges the responsibilities presented.

Patrick Dunbar, 8th Earl of Dunbar, a descendant of the Earls of Northumbria was recognized in the end of the 13th century to use the name March as his earldom in Scotland, otherwise known as Dunbar, Lothian, and Northumbrian border.

Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, Regent of England together with Isabella of France during the minority of her son, Edward III, was a usurper who had deposed, and allegedly arranged the murder of, King Edward II. He was created an earl in September 1328 at the height of his de facto rule. His wife was Joan de Geneville, 2nd Baroness Geneville, whose mother, Jeanne of Lusignan was one of the heiresses of the French Counts of La Marche and Angouleme.

His family, Mortimer Lords of Wigmore, had been border lords and leaders of defenders of Welsh marches for centuries. He selected March as the name of his earldom for several reasons: Welsh marches referred to several counties, whereby the title signified superiority compared to usual single county-based earldoms. Mercia was an ancient kingdom. His wife's ancestors had been Counts of La Marche and Angouleme in France.

In Ireland, a hybrid system of marches existed which was condemned as barbaric at the time.[a] The Irish marches constituted the territory between English and Irish-dominated lands, which appeared as soon as the English did and were called by King John to be fortified.[10] By the 14th century, they had become defined as the land between The Pale and the rest of Ireland.[11] Local Anglo-Irish and Gaelic chieftains who acted as powerful spokespeople were recognised by the Crown and given a degree of independence. Uniquely, the keepers of the marches were given the power to terminate indictments. In later years, wardens of the Irish marches took Irish tenants.[12][13][14]

Titles

[edit]Marquis, marchese and margrave (Markgraf) all had their origins in feudal lords who held trusted positions in the borderlands. The English title was a foreign importation from France, tested out tentatively in 1385 by Richard II, but not naturalized until the mid-15th century, and now more often spelled "marquess".[b]

Related concepts

[edit]This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (November 2010) |

Abbasid Caliphate

[edit]Armenia

[edit]The specific subdivisions of Armenia are each called marz, մարզ (pl. "marzer, մարզեր"), a loanword from Persian.

The Balkans

[edit]See Krajina and Military Frontier.

Byzantine Empire

[edit]China

[edit]The Chinese concept of March is called Fan (藩), referring to feudatory domains and petty kingdoms on the borderlands of the empire.

In their initial development during the later Zhou dynasty, the commanderies (jùn, 郡) functioned as marches, ranking below the dukes' and kings' original fiefs and below the more secure and populous counties (xiàn). As the commanderies formed the front lines between the major states, however, their military strength and strategic importance were typically much greater than the counties'. Over time, however, the commanderies were eventually developed into regular provinces and then discontinued entirely during the Tang dynasty reforms.

Japan

[edit]The European concept of marches applies just as well to the fief of Matsumae clan on the southern tip of Hokkaidō which was at Japan's northern border with the Ainu people of Hokkaidō, known as Ezo at the time. In 1590, this land was granted to the Kakizaki clan, who took the name Matsumae from then on. The Lords of Matsumae, as they are sometimes called, were exempt from owing rice to the shōgun in tribute, and from the sankin-kōtai system established by Tokugawa Ieyasu, under which most lords (daimyōs) had to spend half the year at court (in the capital of Edo).

By guarding the border, rather than conquering or colonizing Ezo, the Matsumae, in essence, made the majority of the island an Ainu reservation. This also meant that Ezo, and the Kurile Islands beyond, were left essentially open to Russian colonization. However, the Russians never did colonize Ezo, and the marches were officially eliminated during the Meiji Restoration in the late 19th century, when the Ainu came under Japanese control, and Ezo was renamed Hokkaidō, and annexed to Japan.

Persia (Sassanid Empire)

[edit]Roman Empire

[edit]Ukraine

[edit]

Ukraine, from the Moscow-centric Russian viewpoint, functioned as a "borderland" or "march" and arguably could have gained its current name, which is derived from a Slavic term that can take on the same meaning (see above for similar in Slovenia, etc.), ultimately from this function.[citation needed] This, though, was merely a continuation of a semi-formal arrangement with the Poles, before escalating feuds, political infighting in Poland, and religious differences (mainly Eastern Orthodox vs. Roman Catholic) saw a loose coalition of Ukrainian lords and independent landowners collectively known as the Cossacks shift to ally with the Russian Empire.

The Cossacks became a significant part of Russian military history in their role as military border/buffer-troops in the Wild Fields of Ukraine. The Tatar slave raids in East Slavic lands brought considerable devastation and depopulation to this area prior to the rise of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. As settlement advanced and the borders moved, the Tsars transferred or formed Cossack units to perform similar functions on other borderlands/marches further south and east in (for example) the Kuban and in Siberia, forming (for example) the Black Sea Cossack Host, the Kuban Cossack Host and the Amur Cossack Host.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "In distant Westminster, where it was impossible to imagine the stress of life in the Irish marches, march law (like Irish law, which Edward I had once described as 'detestable to God and contrary to all laws') was outrightly condemned," notes James F. Lydon [9]

- ^ The styling marquis or marquess is a peculiarity of each title.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 689.

- ^ a b "Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ Lewis 1965.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 689–690.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 690.

- ^ Stephenson, Paul (2004). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900-1204. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 0-521-77017-3.

- ^ Carleton, D., & Phillipps, T. (1841). Sir Dudley Carleton's State Letters, during his Embassy at the Hague, AD 1627. first edited by Thomas Phillipps. Typis Medio-Montanis, impressit C. Gilmour.

- ^ Alexander Bugge (1918). "Navnet Telemark og Grenland" [The name Telemark and Grenland].

- ^ Lydon 1998, p. 81.

- ^ Neville, p. [page needed].

- ^ Lydon 1998, p. [page needed].

- ^ Gwyn, p. [page needed].

- ^ Moore, p. [page needed].

- ^ Otway-Ruthven, p. [page needed].

References

[edit]- Gwyn, Stephen. The History of Ireland. [full citation needed]

- Lewis, Archibald R. (1965). "Chapter 5:Southern French and Catalan Society (778-828)". The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718-1050 (Prin ed.). University of Texas Press.

- Lydon, James F. (1998). The Making of Ireland: from ancient times to the present. p. 81.

- Moore, Thomas. The History of Ireland from the Earliest Kings. [full citation needed]

- Neville, Cynthia J. Violence, custom and law: the Anglo-Scottish border lands in the later Middle Ages. [full citation needed]

- Otway-Ruthven, J.A. A History of Medieval Ireland.[full citation needed]

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Marche". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 689–690. Endnote:

- A. Thomas, Les États provinciaux de la France centrale (1879).