Antonio Francisco Xavier Alvares

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2010) |

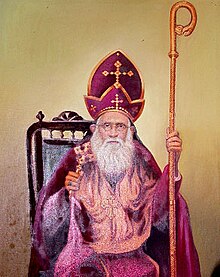

Antonio Francisco Xavier Alvares or Alvares Mar Julius | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| First Metropolitan of Goa and Ceylon | |||||||||||||

| Born | 29 April 1836 Verna, Goa, Portuguese India | ||||||||||||

| Died | 23 September 1923 (aged 87) Ribandar, Goa, Portuguese India | ||||||||||||

| Venerated in | Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church | ||||||||||||

| Major shrine | St. Mary's Orthodox Syrian Church, Ribandar, Goa | ||||||||||||

| Feast | 23 September | ||||||||||||

| Patronage | Poor and Ill | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Antonio Francisco Xavier Alvares (Alvares Mar Julius) (29 April 1836 – 23 September 1923) was initially a priest in the Roman Catholic Church in Goa.[a] He joined the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church and was elevated to Metropolitan of Goa, Ceylon and Greater India in the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church.[1]

Early life

[edit]Alvares was born to a Goan Catholic family in Verna, Goa, Portuguese India.[2]

Priesthood

[edit]Alvares was ordained a Roman Catholic priest in 1862 or 1864 by Bishop Walter Steins SJ, Vicar Apostolic in Bombay. Alvares began his ministry in the Archdiocese of Goa under the Archbishop of Goa. The Portuguese Crown claimed these territories by virtue of old privileges of Padroado (papal privilege of royal patronage granted by popes beginning in the 14th century). The more modern Popes and the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith separated these areas and reorganised them as apostolic vicariates ruled by non-Portuguese bishops, since the English rulers wished to have non-Portuguese bishops.

Successive Portuguese governments fought against this, terming this as unjustified aggression by later Popes against the irrevocable grant of Royal Patronage to the Portuguese Crown, an agitation that spread to the Goan patriots, subjects of the Portuguese Crown.

When, under Pope Pius IX and Pope Leo XIII, the hierarchy in British India was formally reorganised independently of Portugal but with Portuguese consent, a group of pro-Padroado Goan Catholics in Bombay united under the leadership of Dr. Pedro Manoel Lisboa Pinto and Alvares as the Society for the Defense of the Royal Patronage and agitated against the Holy See, the British India government and the Portuguese government in opposition to these changes.

Uniting with Orthodox Church

[edit]Their agitation failed to reverse the changes. Angry with the Portuguese government, the group broke away from the Catholic Church and joined the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church.

Bishop

[edit]Alvares was consecrated as Mar Julius I, on 29 July 1889, by the Orthodox Bishop of Kottayam, Paulose Mar Athanasios to be Archbishop of autocephalous Latin Rite of Ceylon, Goa, and India.

While he was a priest of the Catholic Church, he was in search of the true Biblically Christian One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church. He was against the false devotion and religious exhibitionism. He objected to the Concordat of the Pope and interference of the Government in the Church administration. He could not withstand the harassment meted out to him by the ecclesiastical and civil powers. He went to Western and Eastern Churches and finally came to Malankara and joined the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church. Credited with good faith and piety and true regard for others, he was consecrated as bishop by Joseph Mar Dionysius V, Geevarghese Mar Gregorios of Parumala, Mar Paulose Ivanios Murimattathilof Kandanadu and Mar Athanasios (Kadavil) in Kottayam Old Seminary on 29 July 1889. He was elevated to Metropolitan Archbishop of Goa-India-Ceylon(Presently Brahmavar) Diocese of the Malankara Church

When Joseph René Vilatte was soliciting for consecration by a bishop with orders recognised by the Catholic Church, he was guided[by whom?] to Alvares. Alvares, together with Mar Athanasios Paulose (d. 1907), Bishop of Kottayam, and Saint Geevarghese Mar Gregorios of Parumala (d. 1902), Bishop of Niranam (and later of Thumpamon), consecrated Vilatte in 1892 in Colombo, British Ceylon and named him "Mar Timotheos, Metropolitan of North America," most probably with the blessings of Patriarch of Antioch Ignatius Peter IV.

Alvares has a cathedral under the Syriac Orthodox Church in Colombo, British Ceylon. Alvares had lived in Colombo, Sri Lanka, for a significant time which is why he ended up having a Cathedral at this location. Alvares had also lived in the twin villages of Brahmavar and Kalianpur, Karnataka, which is now where The Evangelistic Association of the East has many churches and has been doing extensive mission work to support the descendants of Alvares converts from his initial missions in these areas and also to continue his missionary work. Alvares died of dysentery in Ribandar, Goa and was buried there.[2]

In Portuguese Goa

[edit]Since Alvares was not allowed by the rulers to work freely in Goa.[3] he was mostly based in Canara region of Karnataka with the main base at Brahmavar. Along with Roque Zephrin Noronha, he worked among the people along the west coast of India from Mangalore to Bombay. About 5000 families joined the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church.[3][need quotation to verify] He ordained Joseph Kanianthra, Lukose Kannamcote and David Kunnamkulam at Brahmawar on 15 October 1911.

Alvares and Pinto continued their efforts to draw many Goans from the Imperial Church and to Orthodoxy. The Brahmavar (Goan) Orthodox Church (BOC) failed in this goal, for outside this group very few Goans moved to this sect.

In British Ceylon

[edit]Alvares was in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) for more than five years. While there he consecrated Vilatte as bishop in the presence of Mar Gregorios of Parumala in 1892.

The denomination that consecrated Vilatte was a part of the Syriac Orthodox Church that had a Latin Rite patrimony. V. Nagam Aiya wrote, in Travancore State Manual, that Alvares "describe[d] his Church as the Latin branch of the Syriac Church of Antioch."[4]

The Holy See sought to consolidate two co-existing jurisdictions, the Padroado jurisdiction and the Congregation for Propagation of the Faith jurisdiction.[5]: 6 The Padroado was the privilege of patronage extended to Portugal which granted the right of designating candidates for episcopal and other offices and benefices in Africa and the East Indies; in addition, it was an exchange of a portion of ecclesiastical revenues for missionaries and endowments to religious establishments in those territories. In time it was seen by the Holy See as an obstacle to missions: the Portuguese government failed to observe the conditions of the agreement; disagreed about the extent of the patronage by claiming the agreement was restricted by Pope Alexander VI's Bulls of Donation and Treaty of Tordesillas while Rome maintained the agreement was restricted to conquered countries; and, contested papal appointments of missionary bishops or vicars apostolic made without its consent, in countries which were never subject to its dominion.[6] As part of the transition, churches served by Goan Catholic priests remained under the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of the East Indies until 1843. Later, this transition was delayed and extended until 1883-12-31. In British Ceylon, it ended in 1887 with the appearance of a papal decree that placed all Catholics in the country under the exclusive jurisdiction of the bishops of the island. That measure met resistance. Alvares and Dr. Pedro Manoel Lisboa Pinto founded in Goa, Portuguese India, an association for the defence of the Padroado. Then, according to G. Bartas, in Échos d'Orient, they complained that the new diocese and vicariates were headed, almost exclusively, by European prelates and missionaries, and petitioned the Holy See for the creation of a purely native hierarchy. Bartas did not state if there was a response, but wrote that Alvares settled the difficulty by reinventing himself as the head of his schism, appearing in Ceylon, and settling into the main old Goan Portuguese churches in the village of Parapancandel.[clarification needed (place name)][7] Alvares was a Roman Catholic Brahmin.[b] Aiya wrote that Alvares, an educated man and the editor of a Catholic journal, was a priest in the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Goa. Failing to maintain amicable relations with the Patriarch of the East Indies, Alvares left the RCC and joined Mar Dionysius the Metropolitan in Kottayam who consecrated Alvares as bishop.[4][c] Later, he returned with the title of Alvares Mar Julius Archbishop of Ceylon, Goa and the Indies, and involved in his schism about 20 parishes in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Jaffna and in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Colombo on the island.[7][12]: 6

Michael Roberts, in Sri Lanka Journal of Social Science, describes three groups within early nationalism in British Ceylon. The most prominent group, "ultra-moderate constitutionalists", with culture and value system significantly westernised, whose main goal was greater participation in government; the second group, "mild-radicals", represented by leaders like Pinto, was a labour movement with political radicalism and interest in more radical trade unions; the third group, "religio-cultural revitalists", traditional values Sinhalese Buddhists "which expressed militant objection to changes produced by Western penetration." Roberts wrote all three groups interacted with the others and had indigenous, Indian, and Burgher people among members, in a complex social tapestry whose members also changed group affiliations over time.[14]: 88 A strike at the largest publisher in Colombo, influenced by Pinto's propaganda, took place in September 1893. The next day, Pinto became president of the newly formed printers union. "The main grievances of the printers included low pay and bad working and living conditions."[15]: 199 [d]

According to Peter-Ben Smit, in Old Catholic and Philippine Independent Ecclesiologies in History, the Union of Utrecht's (UU) International Old Catholic Bishops' Conference (IBC) discussed a ICMoC request for admission in 1902. Smit observed that past "experiences had made ... the IBC cautious, which in his opinion was a reason for the failure of contacts with groups in ... Ceylon ... and other countries to develop into relationships of full communion."[16]: 193, 196 La Croix, Catholic Messenger of Ceylon reported that the Alvares schism ended in 1902.[17] Bartas did not recount the significance of Alvares' ideology,[e] he only noted that the schism, around 1902, intended to convert corporately, to eastern orthodoxy. The cathedral in Colombo had one priest, Alvares, fairly advanced in age. He and his parishioners asked the Holy Synod of the Church of Greece, in Athens, to accept them under its jurisdiction and to send them an officiating priest preaching in Latin and English. Bartas wrote:

A Greek Orthodox priest, delegated by the Holy Synod in Athens, to celebrate the Latin Mass and deliver the English sermons, in an independent Catholic Church of Ceylon in the cathedral of the priest who became Archbishop of Goa Indo-Ceylon by the grace of a Jacobite bishop of Malabar; that is the answer to a purely indigenous hierarchy, that ... Pinto and Alvarez demanded so loudly at the beginning of their schism![7]

But the Greek Holy Synod reflected on information provided by the Archimandrite Germain Kazakis, head of the Orthodox settlement of Calcutta, in addition to the parishioners' application in which they declared themselves Orthodox but still held Roman Catholic liturgies, sacraments, and devotions. According to Smit, "presumably seeing an analogy between the respective emergences of the two churches," Stephen Silva, the ICMoC secretary, complained to Gregorio Aglipay of the Philippine Independent Church in 1903 that the ICMoC "cannot get sufficient priests to work independently of Rome."[16]: 258 Bartas wrote, in 1904 that the Greek Holy Synod "will undoubtedly continue to defer its response" under these conditions.[7] Smit mentioned that the ICMoC also failed to create "a relationship with the Greek Orthodox Church in the 1910s."[16]: 258 In 1913, Adrian Fortescue described Alvares' faction, in The Lesser Eastern Churches, as "chiefly famous for the begging letters they write and the doubt they cause to people who receive these letters as to who exactly they may be."[13]

Educator

[edit]Alvares was a scholar, man of high principles and had a formidable personality. He opened a college where Goan priests were teaching Portuguese, Latin, French, and Philosophy. In 1912, Alvares opened an English School in Panaji. Both operated for a short time.

Social worker

[edit]At that time Goa was frequently affected by epidemic like malaria, typhoid, smallpox, cholera and plague. Alvares published a pamphlet on the treatment of cholera. He was concerned about the shortage of food in Goa and appealed to the people to produce cheaper food.[citation needed] He published a booklet about the cultivation of cassava.

Apostle of charity

[edit]In 1871, he started a charitable association in Panaji to render help to the poor, beginning with wandering beggars. After a few years he extended the association to other cities in Goa. During the last ten years of his life he concentrated his activities in Panaji. His home accommodated the poor and destitute as well as lepers and tuberculosis patients.[further explanation needed] He was a beggar without an income. One day Alvares requested a shopkeeper for a contribution, but the shopkeeper spat in the bowl. Without getting angry, Alvares said, "All right, I shall keep this for me. Now, give something for the poor." The shopkeeper contributed generously.

Excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church

[edit]This designation was given to Alvares by Goan historians.[specify] After joining the Orthodox Church, Alvares was excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church. He was persecuted by the Catholic Church and the Portuguese Government.[18] Though he was advised by some of his old friends to reunite with the Catholic Church, especially when he was very sick, he refused and stuck to his Orthodox faith.

Martyr

[edit]

Alvares embraced the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church. He was excommunicated and persecuted. He was arrested,[further explanation needed] stripped of his episcopal vestments and taken through the street in his underwear to the police lock-up and placed into a filthy prison cell without a bed or chair. He was forcibly deprived of his cross and the ring, the episcopal insigne he was wearing. He was beaten and presented in the court. But the government could not prove the allegations[clarification needed] and he was acquitted. After a few days, he was arrested again and charged with the offence of high treason,[further explanation needed] but again the Justice found him innocent. He was no longer allowed to use his episcopal vestments and wore a black robe.[further explanation needed] When he was persecuted, none of the Orthodox Church people were nearby because he had no support or person in Goa from the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church.[citation needed]

Death

[edit]Alvares died of dysentery on 23 September 1923 in Ribandar hospital, a charitable institution. He wished to be buried by Orthodox designates and was specific not to have any Catholic priest for the same. The citizen committee led by the Chief Justice arranged a grand funeral.[citation needed] His body lay in state in the Municipal Hall for 24 hours. The newspapers were full of articles and obituaries about Alvares.[citation needed] Though Alvares was considered an enemy by the government,[citation needed] the Governor General sent his representative. Thousands of people especially poor and beggars paid their last respects.[citation needed] Funeral speeches were made by high dignitaries. The day after his death, a funeral procession wound through all the main roads of Panaji and ended in a secluded corner of St. Inez cemetery where his body was laid to rest without any funeral rites.[further explanation needed]

Veneration

[edit]

In 1927, his bones were collected by his friends and admirers[who?], placed in a lead box and reburied, under a marble slab with the inscription "Em Memoria De Padre Antonio Francisco Xavier Alvares, Diue [sic] Foi Mui Humanitario Missionario E Um Grade [sic] Patriota" (In memory of priest Antonio Francisco Xavier Alvares, who was very humanitarian missionary and a great patriot) and the largest cross in the cemetery.

In 1967, John Geevarghese, the first resident Vicar of St. Mary’s Orthodox Church, Goa, rediscovered the forgotten grave of Alvares, and brought Metropolitan Mathews Mar Athanasios of the Outside Kerala Diocese to Goa to conduct services befitting an Orthodox bishop at the burial site.[19] A small church was constructed in Ribandar and, in 1979, Alvares' remains were disinterred and placed in the church by Metropolitan Philipose Mar Theophilos of the Bombay diocese.

When the St. Mary's church was reconstructed in the same place, Alvares' remains were moved to the present ossuary which was specially made on the side of the altar by Moran Mar Baselios Mar Thoma Mathews II, Catholicos of the East, on 6 October 2001.

Alvares' remains are entombed at St. Mary's Orthodox church in Ribandar. Although the congregation was small, the Brahmavar Orthodox Community has survived almost a century after Alvares' death. His dukrono, a memorial feast, is celebrated at St. Mary's Orthodox Syrian church in Ribandar on 23 September every year.

Works or publications

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

- Universal Supremacy in the Church of Christ ... Abridged from the original in Portuguese. Colombo: Clifton Press. 1898. OCLC 771049027.

- Directions for the Treatment of Cholera ... (pamphlet) (2nd ed.). Ceylon: Victoria Press. 1896. OCLC 771049026.

Newspapers

[edit]Alvares started a number of periodicals; most of them were educative and supportive of the right of the public.[citation needed] He was a critic of the government.[clarification needed] Most of the periodicals were banned and forced to stop publications after few years.[citation needed]

- A Cruz (in Portuguese)

- A Verdade (in Portuguese)

- O Brado Indiano (in Portuguese)

- O Progresso de Goa (in Portuguese)

- Times of Goa (in Portuguese)

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Sometimes his surname is mistakenly spelled "Alvarez" instead of the standard Portuguese form "Alvares".

- ^ Aiya and Richards use brahman;[4][8]: 64 a member of the first of the four castes of Hinduism, a sacerdotal class.[9] Pearson uses brahmin;[10]: 129 a broader term that also includes a scholar, teacher, priest, intellectual, researcher, scientist, knowledge-seeker, or knowledge worker.[11]

- ^ Marx and Blied noted that Fortescue believed Alvares was consecrated by the reformed group.[12]: 7 [13]

- ^ See Jayawardena, Kumari (1972). The rise of the labor movement in Ceylon. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 93–97. ISBN 0-8223-0268-3.[15]: 199, 216

- ^ For Alvares' swadeshi mindset see Kamat, Pratima P (29 April 2012). "Remembering H G Alvares: Mar Julius". Navhind Times (online ed.). Panaji, IN: Navhind Papers & Publications. OCLC 60632493. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

References

[edit]- ^ Kiraz, George A (July 2004). "The Credentials of Mar Julius Alvares, Bishop of Ceylon, Goa and India Excluding Malabar". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 7 (2). Piscataway, NJ: Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute and Gorgias Press: 158. ISSN 1097-3702. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2004. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ a b "His Grace Alvares Mar Julius Metropolitan". StAlvares.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2007.

- ^ a b Cheeran, Joseph (2009). The Indian Orthodox Church of St. Thomas, AD 52-2009. Translated by Annie David (2nd ed.). Kottayam: K.V. Mammen Kottackal Publishers. p. 306. OCLC 768294822.

- ^ a b c

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Aiya, V. Nagam (1906). Travancore State Manual. Vol. 2. Trivandrum, IN: Travancore Government Press. p. 200. hdl:2027/umn.31951p00335772y. OCLC 827203062. Retrieved 14 May 2013. Here, the surname Alvares is spelled Alvarez.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Aiya, V. Nagam (1906). Travancore State Manual. Vol. 2. Trivandrum, IN: Travancore Government Press. p. 200. hdl:2027/umn.31951p00335772y. OCLC 827203062. Retrieved 14 May 2013. Here, the surname Alvares is spelled Alvarez.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: s.n. (July 1899). "Recent Schismatical Movements Among Catholics in the United States" (PDF). American Ecclesiastical Review. 21 (1). New York, NY: American Ecclesiastical Review: 1–13. LCCN 46037491. OCLC 9059779. Archived from the original on 18 May 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: s.n. (July 1899). "Recent Schismatical Movements Among Catholics in the United States" (PDF). American Ecclesiastical Review. 21 (1). New York, NY: American Ecclesiastical Review: 1–13. LCCN 46037491. OCLC 9059779. Archived from the original on 18 May 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Brucker, Joseph (1911). "Protectorate of Missions". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Brucker, Joseph (1911). "Protectorate of Missions". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b c d

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Bartas, G (November 1904). "Coup d'oeil sur l'Orient greco-slave". Échos d'Orient (in French). 7 (49). Paris: Institut Francais des Etudes Byzantines: 371–372. doi:10.3406/rebyz.1904.3573. LCCN sc82003358. Here, the surname Alvares is spelled Alvarez.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Bartas, G (November 1904). "Coup d'oeil sur l'Orient greco-slave". Échos d'Orient (in French). 7 (49). Paris: Institut Francais des Etudes Byzantines: 371–372. doi:10.3406/rebyz.1904.3573. LCCN sc82003358. Here, the surname Alvares is spelled Alvarez.

- ^ Richards, William J (1908). The Indian Christians of St. Thomas: otherwise called the Syrian Christians of Malabar (PDF). London: Bemrose & Sons. OCLC 5089145. Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^

The dictionary definition of brahman at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of brahman at Wiktionary

- ^ Pearson, Joanne (2007). Wicca and the Christian Heritage: Ritual, sex and magic. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-96198-8. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^

The dictionary definition of brahmin at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of brahmin at Wiktionary

- ^ a b Marx, Joseph A; Blied, Benjamin J (January 1942). "Joseph Rene Vilatte". The Salesianum. 37 (1). Milwaukee, WI: Alumni Association of St. Francis Seminary: 1–8. hdl:2027/wu.89064467475. ISSN 0740-6525.

- ^ a b Fortescue, Adrian (1913). The Lesser Eastern Churches (PDF). London: Catholic Truth Society. p. 372. OCLC 551695750. Archived from the original on 21 June 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ Roberts, Michael (1981). "Hobgoblins, low-country Sinhalese plotters, or local elite chauvinists?" (PDF). Sri Lanka Journal of Social Science. 4 (2). Colombo: Social Science Research Centre, National Science Council of Sri Lanka: 83–126. ISSN 0258-9710. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ a b Colin-Thome, Percy (January–December 1985). "The Portuguese Burghers and the Dutch Burghers of Sri Lanka" (PDF). Journal of the Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon. 62 (1–4). Colombo: Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon: 199, 216. OCLC 29656108. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Smit, Peter-Ben (2011). Old Catholic and Philippine Independent Ecclesiologies in History: The Catholic Church in every place. Brill's Series in Church History. Vol. 52. Leiden: Brill. pp. 50, 180–285. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004206472.i-548.19. ISBN 978-9004206472. ISSN 1572-4107.

- ^ "La fin d'un schisme aux Indes". La Croix (in French). Paris. 12 July 1902. p. 3. ISSN 0242-6412. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Daniel, David. St Thomas Christians. p. 245.[place missing][publisher missing][year missing]

- ^ "Former Vicars". St Mary's Orthodox Syrian Church.

Further reading

[edit]- Alexander, George; Philip, Ajesh (2018). Western rites of syriac-malankara orthodox churches (1st ed.). OCP Publications. ISBN 978-1387803163.

- Azevedo, Carmo (1988). Patriot & Saint: The life story of Father Alvares/Bishop Mar Julius I. Panjim, IN: Azevedo. LCCN 88905901. OCLC 556945748. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- Kamat, Pratima P (29 April 2012). "Remembering H G Alvares: Mar Julius". Navhind Times (online ed.). Panaji, IN: Navhind Papers & Publications. OCLC 60632493. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- Pinto, Rochelle (2007). Between empires: print and politics in Goa. SOAS studies on South Asia. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195690477.

- Indian Oriental Orthodox Christians

- 19th-century Indian Roman Catholic priests

- Scholars from Goa

- People from Verna, Goa

- 1836 births

- 1923 deaths

- Christian missionaries in Sri Lanka

- Colonial Goa

- People acquitted of treason

- People excommunicated by the Catholic Church

- Syriac Orthodox Church bishops

- Oriental Orthodox missionaries

- Converts to Oriental Orthodoxy from Roman Catholicism