Watervliet, New York

Watervliet | |

|---|---|

Watervliet as seen when entering the city on Congress Street Bridge from Troy | |

| Etymology: from Dutch 'water brook, water stream' | |

| Nickname: The Arsenal City | |

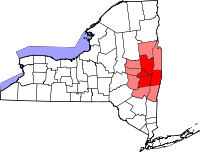

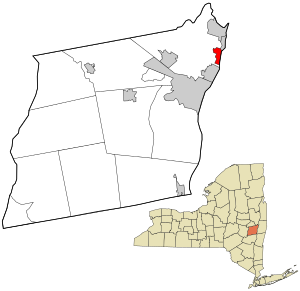

Location in Albany County and the state of New York. | |

Location of New York in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 42°43′29″N 73°42′22″W / 42.72472°N 73.70611°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Albany |

| Incorporation as city | 1896 |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Hall |

| • Mayor | Charles Patricelli (D) |

| • General Manager | Joseph LaCivita |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.47 sq mi (3.81 km2) |

| • Land | 1.34 sq mi (3.48 km2) |

| • Water | 0.13 sq mi (0.34 km2) |

| Elevation | 30 ft (9 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 10,375 |

| • Density | 7,731.00/sq mi (2,985.58/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 12189 |

| Area code | 518 |

| FIPS code | 36-001-78674 |

| FIPS code | 36-78674[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0968918[3] |

| Wikimedia Commons | Watervliet, New York |

| Website | www |

Watervliet (/wɔːtərˈvliːt/ waw-tər-VLEET or /wɔːtərvəˈliːt/ waw-tər-və-LEET) is a city in northeastern Albany County, New York, United States. The population was 10,375 as of the 2020 census.[4] Watervliet is north of Albany, the capital of the state, and is bordered on the north, west, and south by the town of Colonie. The city is also known as "the Arsenal City".[5]

History

[edit]The explorer Henry Hudson arrived in the area of Watervliet around 1609. The area was first settled in 1643 as part of the Rensselaerswyck patroonship, under the direction of Kiliaen van Rensselaer. In 1710, Derrick van der Heyden operated a ferry from the Bleeker Farm (near 16th Street) across the Hudson River to Troy. Troops during the Revolutionary War used this ferry in 1777 on their way to Bemis Heights and Stillwater for the Battle of Saratoga. In 1786, a second ferry was started at Ferry Street (today 14th Street) over to Troy.[6] The town of Watervliet was founded in 1788 and included all of present-day Albany County except what was in the city of Albany at the time. Because so many towns had been created from the town of Watervliet, it is regarded as the "mother of towns" in the county.[citation needed] In 1816, as the first post office was erected, corner of River and Ferry streets (Broadway and 14th Street), it took the name Watervliet.[6]

In the mid-1700s, the area of Watervliet was also known as Bought, or Boght, named after the Dutch word "bocht," meaning "bend" or "corner." This is reflected in contemporary Revolutionary War pension service records.

The location of the future city was taken by the village of Gibbonsville (1824) and its successor West Troy, and the hamlet of Washington (later Port Schuyler).[7] The farm owned by John Bleeker, stretching north from Buffalo Street (Broadway and 15th Street) to the farm owned by the Oothout family near 25th Street was purchased by Philip Schuyler, Isais Warren, Richard P. Hart, Nathan Warren, and others in 1823; they named it West Troy. Gibbonsville was the farm of James Gibbons (which he purchased in 1805), which stretched from North Street (8th Street) to Buffalo Street (15th Street).[6] Washington was settled sometime before 1814 and was the area south of Gibbonsville and today the area of Watervliet south of the Arsenal; it became known as Port Schuyler in 1827.[7] Although Gibbonsville and West Troy sat side by side (West Troy lying on Gibbonsville's northern boundary), there was a rivalry between the two and each named and laid out their streets with no regard to the street names and grids of the other.[7] In 1824 Gibbonsville became incorporated as a village, and in 1836 this was repealed when West Troy became incorporated as a village including Gibbonsville and Port Schuyler;[7] and in 1847 the Watervliet post office changed its name to West Troy.[8] In 1830, Gibbonsville had 559 people, West Troy 510, and Port Schuyler 450.[8]

In 1865, present-day Watervliet was included in the Capital Police Force within the Troy District. This attempt at regional consolidation of municipal police failed and in 1870 the West Troy Police Force was organized.[6]

By 1895, what was known as the town of Watervliet was reduced to the present-day city of Watervliet (village of West Troy at the time), town of Colonie, and the village/town of Green Island. Colonie would split off in 1895, and the city of Watervliet was incorporated in 1896 at the same time that Green Island became a town of its own.[citation needed]

In the early 19th century Watervliet became a major manufacturing community much like its neighbors Cohoes and Troy, thanks to bell foundries. The first was located on Water Street (Broadway), between 14th and 15th Streets, by Julius Hanks, and the first bell foundry in Gibbonsville was established in 1826 by Andrew Menelly, Sr.[6] This would be the genesis of the Meneely Bell Foundry, which made thousands of bells that are still in use today from Iowa to the Czech Republic.[citation needed]

In 1813, the U.S. Federal Government purchased from James Gibbons 12 acres (49,000 m2) in Gibbonsville, in 1828 another 30 acres (120,000 m2), along with later purchases from S. S. Wandell and others.[6] This land was used as the site for the Watervliet Arsenal, founded in 1813 during the War of 1812, and is the sole manufacturing facility for large caliber cannon.[citation needed] John C. Heenan, U.S. heavyweight boxing champion and contender for the world title in 1860, was once employed at the Arsenal.[6]

The main route of the Erie Canal from Buffalo to Albany ran through Watervliet, and because the canal bypassed the city of Troy, the city's business community decided a "short cut" was needed for convenient access to the Erie Canal without having to go through the Albany Basin. A side-cut to the Hudson was at Watervliet's present-day 23rd Street (the Upper Side cut) finished in 1823,[7] and another just south of the Arsenal (the Lower Side cut).[9] A weigh station and a center for paying canal boat operators was here as well.[citation needed] As a result of canal boat crews being paid at the end of their trip, the areas around the side cut was once famous for gambling, saloons, and prostitution; there were more than 25 saloons within two blocks,[9] with names like The Black Rag and Tub of Blood.[10] The neighborhood around the side cut had the nickname of "Barbary Coast of the East", Buffalo being the "Barbary Coast of the West".[9][10] In the 1880s, Watervliet had a reputation for over 100 fights a day and a body once a week in the Canal.[10]

Also linking Watervliet to the transportation network of the region was the Watervliet Turnpike and the Albany and Northern Railway. The Watervliet Turnpike Company in 1828 built present-day New York State Route 32 from the northern boundary of Albany north to the northern limit of Gibbonsville (now Broadway and 15th Street).[6] The Albany and Northern Railway was built in 1852 connecting Watervliet to Albany, with a depot on Genesee Street; a few years later a new depot was built on Canal Street (Central Avenue) but was abandoned in favor of returning to the original location in 1864.[7]

As of February 2020, the Mayor of Watervliet is Charles Patricelli, a Democrat who won the 2019 election unopposed.[11][12]

The Ohio Street Methodist Episcopal Church Complex, St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Church, Watervliet Arsenal, and Watervliet Side Cut Locks are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[13]

St. Patrick's Church controversy

[edit]

In September 2011, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany decided to close St. Patrick's Roman Catholic Church, citing physical deterioration of the building. The parish was merged with Immaculate Heart of Mary Parish, and was unable to afford the estimated $4 million cost to rehabilitate the building.[14] Built in 1889,[15] St. Patrick's Church was the tallest point in the city.[16] The church was closely modeled on the Upper Basilica in Lourdes, and many Watervliet residents considered it a defining piece and landmark of the city's architecture.[17]

In March 2012, a developer filed a proposal to rezone the property from residential to business status so that it could raze the church (as well as an attached rectory, former school building, and six private residences) in order to make way for a Price Chopper grocery store.[14][18] Some members of the community responded to the proposal to raze the church with criticism and legal challenges,[19][20][21][22] but on November 20, 2012, the Watervliet City Council voted unanimously to allow the rezoning.[23] The deconstruction of the church was completed in May 2013,[24] and a new Price Chopper supermarket opened on the site in July 2014.[25]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 1.5 square miles (3.8 km2), of which 1.4 square miles (3.5 km2) is land and 0.12 square miles (0.3 km2), or 8.79%, is water.[4]

Watervliet is bordered on three sides by the town of Colonie (on the north by the hamlet of Maplewood, on the west by the hamlets of Latham and Mannsville, and on the south by the hamlet of Schuyler Heights). The northeastern corner of Watervliet is bounded by the town and village of Green Island. South of Green Island, Watervliet is bounded on the east by the Hudson River (which is the boundary between Albany County and Rensselaer County). The city of Troy is across the river from Watervliet. Watervliet is mostly flat, but begins an extreme slope in the center of its most westerly edge (especially between the Watervliet Arsenal and 19th Street, an area once called "Temperance Hill").[citation needed]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 4,572 | — |

| 1850 | 6,900 | +50.9% |

| 1860 | 8,952 | +29.7% |

| 1870 | 10,693 | +19.4% |

| 1880 | 8,820 | −17.5% |

| 1890 | 12,967 | +47.0% |

| 1900 | 14,321 | +10.4% |

| 1910 | 15,074 | +5.3% |

| 1920 | 16,073 | +6.6% |

| 1930 | 16,083 | +0.1% |

| 1940 | 16,114 | +0.2% |

| 1950 | 15,197 | −5.7% |

| 1960 | 13,917 | −8.4% |

| 1970 | 12,404 | −10.9% |

| 1980 | 11,354 | −8.5% |

| 1990 | 11,061 | −2.6% |

| 2000 | 10,207 | −7.7% |

| 2010 | 10,254 | +0.5% |

| 2020 | 10,375 | +1.2% |

| Notes: Census numbers for 1840 to 1890 are for the village of West Troy (incorporated 1836), which became the city of Watervliet in 1896. *1880 census was not considered accurate and estimates put population at roughly 11,000*[8] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[26] | ||

As of the census[2] of 2020, there were 10,375 people and 5,070 households residing in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 76.9% White, 9.0% African American, 4.7% Asian, 2.3% from other races, and 7.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.0% of the population.

There were 5,070 households, out of which 26.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 32.9% were married couples living together, 16.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.4% were non-families. 38.3% of all households were made up of individuals. The median income for a household in the city was $46,345. 21.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 21.7% of those under age 18 and 5.7% of those age 65 or over.

Notable people

[edit]- Richard B. Bates, member of the Wisconsin State Assembly

- Butch Byrd, defensive back, Buffalo Bills

- T/Sgt. Peter J. Dalessandro, Medal of Honor recipient

- Melique García, Olympic Sprinter

- Rebecca Cox Jackson (1795–1871), African-American freedwoman, Shaker, itinerant minister, and spiritual autobiographer

- Isaac J. Lansing, president of Clark Atlanta University, pastor, author

- Francis W. Martin (1878-1947), first District Attorney of the Bronx

- Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University, lawyer, president of Southern Pacific Railroad

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Watervliet city, New York". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ Sanzone, Danielle. "Former police chief allegedly stole money from funeral home". The Record.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Myers, James T. "History of the City of Watervliet: 1630–1910". Henry Stowell & Son. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Howell, George (1886). Bi-centennial History of County of Albany, 1609–1886. W.W. Munsell & Company. pp. 974–993. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

bi-centennial history of county of albany.

- ^ a b c Weise, Arthur James (1886). The city of Troy and its vicinity. Troy, New York: Edward Green. p. 341. OCLC 8989214.

- ^ a b c "Erie Canal". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c Lionel D. Wyld (1962). Low Bridge!: Folklore and the Erie Canal. Syracuse University Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780815601371. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ "Watervliet mayor sees growth in future". Times Union. February 21, 2020.

- ^ Buonanno, Nicholas. "Patricelli eager to serve as next Watervliet mayor". The Record.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Crowe, Kenneth (May 30, 2012). "St. Patrick's public hearing in Watervliet Wednesday". Times Union. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ Gardinier, Bob (March 28, 2013). "Final bell fails to save St. Patrick's". Times Union.

- ^ Sanzone, Danielle. "Cross, bell removed from St. Patrick's Church in Watervliet". The Record.

- ^ Gardinier, Bob (May 20, 2013). "St. Patrick's was 'our work of art'". Times Union.

- ^ "Update: St. Patrick's demolition (pictures and video)". Times Union. April 23, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ Churchill, Chris (April 28, 2012). "A prayer of a chance for St. Patrick's?". Times Union. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ Morrow, Ann (April 26, 2012). "Is Nothing Sacred?". Metroland. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ Sanzone, Danielle (January 14, 2013). "Another lawsuit filed to save Watervliet's St. Patrick's Church". The Record.

- ^ Crowe, Kenneth C. (March 12, 2013) St. Patrick's demolition fight heats up. Times Union. Retrieved on 2017-02-05.

- ^ Crowe, Kenneth C. (November 20, 2012) Vote OKs razing of St. Patrick's. Times Union. Retrieved on 2017-02-05.

- ^ Crowe, Kenneth C. (May 20, 2013) Last chapter shuts on St. Patrick's. Times Union. Retrieved on 2017-02-05.

- ^ "New Price Chopper in Watervliet". Times Union. July 11, 2014.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.