Mahdism

Mahdism (Persian: مَهدَویّت,[1] Arabic: المهدوية) in the Twelver branch of Shia Islam, derived from the belief in the reappearance of the Twelfth Shiite Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, as the savior of the apocalypse for the salvation of human beings and the establishment of peace and justice. Mahdism is a kind of messianism. From this perspective, it is believed that Jesus Christ and Khidr are still alive and will emerge with Muhammad al-Mahdi in order to fulfil their mission of bringing peace and justice to the world.[2][3][4]

Mahdism in Quran

[edit]Many verses of the Quran are related to Mahdism,[5][6] such as verse 105 of Al-Anbiya Surah:

«وَ لَقَدْ کَتَبْنَا فیِ الزَّبُورِ مِن بَعْدِ الذِّکْرِ أَنَّ الْأَرْضَ یَرِثُهَا عِبَادِیَ الصَّالِحُون»

"Certainly We wrote in the Psalms, after the Torah: ‘Indeed My righteous servants shall inherit the earth’."

The commentators have considered the fulfillment of the promise mentioned in the verse at the time of the reappearance of Imam Muhammad al-Mahdi.[7][8] Also, verse 5 of Al-Qasas Surah:

«وَ نُرِیدُ أَن نَّمُنَّ عَلیَ الَّذِینَ اسْتُضْعِفُواْ فیِ الْأَرْضِ وَ نجَعَلَهُمْ أَئمَّةً وَ نجَعَلَهُمُ الْوَارِثِین»

"And We desired to show favour to those who were abased in the land, and to make them imams, and to make them the heirs"

Some have considered the interpretations of this verse to be related to Muhammad al-Mahdi[9][10] and others have considered it to be related to the return (Rajʽa) of the Imams and the return of the government to them.[11][12][13] Verse 55 of Surah An-Nur:

«وَعَدَ اللَّهُ الَّذِینَ ءَامَنُواْ مِنکمُ وَ عَمِلُواْ الصَّلِحَتِ لَیَسْتَخْلِفَنَّهُمْ فیِ الْأَرْضِ کَمَا اسْتَخْلَفَ الَّذِینَ مِن قَبْلِهِمْ وَ لَیُمَکِّنَنَّ لهُمْ دِینهَمُ الَّذِی ارْتَضیَ لهَمْ وَ لَیُبَدِّلَنهُّم مِّن بَعْدِ خَوْفِهِمْ أَمْنًا یَعْبُدُونَنیِ لَا یُشْرِکُونَ بیِ شَیْا وَ مَن کَفَرَ بَعْدَ ذَالِکَ فَأُوْلَئکَ هُمُ الْفَاسِقُون»

"Allah has promised those of you who have faith and do righteous deeds that He will surely make them successors in the earth, just as He made those who were before them successors, and He will surely establish for them their religion which He has approved for them, and that He will surely change their state to security after their fear, while they worship Me, not ascribing any partners to Me. Whoever is ungrateful after that—it is they who are the transgressors"

Also it is known to be related to Mahdism issues. Some have considered the fulfillment of the promise mentioned in the verse at the time of the reappearance of the Twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi[14] and some have considered the community mentioned in the verse to be achievable only at the time of the reappearance of Muhammad al-Mahdi.[15]

Mahdism in Twelver branch

[edit]The Shiites of the Twelver branch of Shia Islam believe that according to the divine promise, a descendant of Muhammad, Prophet of Islam or his namesake, the ninth child of the descendants of Husayn ibn Ali, will appear with the epithet of "Mahdi"[18] and will spread justice throughout the earth.[19]

According to this belief, Mahdi, the son of Hasan al-Askari (the eleventh Shiite Imam), was born in 870 CE. Upon the death of his father, while he was still a child, after the early years of his Imamate, he disappeared and would only contact his followers through his four successive deputies.[20][21] The period of the so-called minor occultation or first occultation, in which Mahdi was not in direct contact with the people, only through his special deputies,[22] which was mostly in contact with the Shiites. According to official tradition, in 940 CE, the fourth and last delegate received a final letter signed by the hidden Imam in which he declared that henceforth and "until the end of time," no one will see him or be his representative, and that whosoever declares otherwise is no less than an imposter. Thus a long absence began, the so-called major occultation or second occultation.[21]

Some late Shiite scholars who have questioned or rejecting Mahdism include Abolfazl Borqei Qomi,[23][24] Heidar Ali Qalmadaran Qomi, and Mohammad Hassan Shariat Sanglaji.[25]

Among the present scholars who have worked on Mahdism is Lotfollah Safi Golpaygani. He has two important works in this field, Selected Trace About the Twelfth Imam[26][27] and Imamate and Mahdism[28][29]).[30][31]

Mahdism in other Shiite branches

[edit]One of the events that spread the idea of Mahdism was the sudden death of Ismail, the son of Ja'far al-Sadiq (the sixth Imam of the Shiites), in 762 CE, who, according to the Isma'ilism Shiites, had previously been appointed as the seventh Imam of the Shiites. Although most Shiites gathered around Ja'far al-Sadiq's other son, Musa al-Kadhim, a minority of Shiites did not accept Ismail's death, claiming that Ismail was still alive and hiding himself. According to them, Ismail is the absent Imam.[32] With the rise of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt, the epithet of "Mahdi" was attributed to the first Fatimid caliph and his successors, citing hadiths narrated by the Isma'ilists and other sources. However, the Isma'ilists expect the seventh Isma'ili Imam to appear under the name of Qa'im at the end of time.[33]

In the Zaidi Shi'ism sect, who do not consider the Imams to have superhuman powers, belief in Mahdism is very inconspicuous. Throughout history, many people have been considered as "Mahdi" or claimed to be alive and absent. One of them was Husayn ibn Qasim Ayani, the leader of a sect branching out from Zaidi Shi'ism, called the Husaynieh sect. A group denied his death and claimed him as "Mahdi" and believed that he would return. But this beliefs about these people is not recognized by the Zaidi Shi'ism majority.[33]

Mahdism in Sunni branch

[edit]According to Reza Aslan, with the development of the Mahdism doctrine among the Shiites, Sunni jurisprudence scholars tried to distance themselves from belief in the Mahdi.[32] According to Wilferd Madelung, despite the support of belief in the Mahdi by some important Sunni traditionists, belief in the Mahdi has never been considered as one of the main beliefs of Sunni jurisprudence. The Mahdi is mentioned in Sunni beliefs, but rarely. Many prominent Sunni scholars, such as Al-Ghazali, have avoided discussing this issue. Of course, according to Madelung, this avoidance was less due to disbelief in the Mahdi[33] and more (according to Reza Aslan) due to wanting to avoid disputes and social riots.[32][33]

There are exceptions such as Ibn Khaldun in the book "Muqaddimah" who openly opposes belief in the Mahdi and considers all hadiths related to the Mahdi to be fabricated. There are different views among the traditionists and scholars who have dealt with the Mahdism issue. The epithet of "Mahdi" has been mentioned many times in the book "Musnad" by Ahmad ibn Hanbal (founder of the Hanbali school of Sunni jurisprudence — one of the four major orthodox legal schools of Sunni Islam, and also one of the four Sunni Imams) and various hadiths about the signs of the reappearance of the "Promised Mehdi" (and Jesus in his cooperation) mentioned there. Ahmad ibn Hanbal has narrated in his work that:

Sufyan ibn ʽUyaynah from Aasim ibn Abi al-Najud, narrated a hadith from Abdullah ibn Masud [a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad] from the Prophet Muhammad:

«لا تقوم الساعة حتی یلی رجل من اهل بیتی، یواطی ء اسمه اسمی.»

"The resurrection will not take place until a man from my family namesake with me emerges."[34]

In mentioning the importance and validity of Ahmad ibn Hanbal's "Musnad" among the Sunnis, it is enough that Taqi al-Din al-Subki writes on page 201 of the first volume of "Tabaqat al-Shafeiyah":[35]

"Ahmad ibn Hanbal's Musnad is one of the basis of Muslim beliefs"

— Taqi al-Din al-Subki, "Tabaqat al-Shafeiyah", 1st volume, p. 201

Also Al-Suyuti, a Sunni Egyptian Muslim scholar, has discussed the validity of Ahmad ibn Hanbal among Sunnis in the introduction to the book "Jam al-Javameh".[36] Ali ibn Abd-al-Malik al-Hindi, the author of Kanz al-Ummal, says in that book:

«کل ما فی مسند احمد حنبل فهو مقبول»

"What is in the book "Musnad" of Ahmad ibn Hanbal is accepted by the Sunnis."[37]— "Kanz al-Ummal", 1st volume, p. 3

In some hadiths in Sunni books, "Mahdi" is the same as "Jesus Christ", while in other narrations there is no mention of the identity of that person, or it is said that "he rises with Jesus." The Mahdi is also mentioned as one of the descendants of Husayn ibn Ali, the descendants of Hasan ibn Ali or the son of Hasan al-Askari, the twelfth Imam of Shiites.[33] Throughout history to the present day, there have been long debates among Sunni scholars about the "savior" role and the "political" role of the Mahdi.[32]

But according to Seyyed Hossein Nasr, the Sunnis believe that the Mahdi is from the family of Muhammad, the Prophet of Islam and will emerge with Jesus in the end times. He also writes that the belief in the coming of the Mahdi is so strong among Muslims that throughout history, especially in times of pressure and hardship, has led to the emergence of claimants of "Mahdism".[38] Contemporary Sunni writers such as Abd al-Muhsin al-Ibad, Muhammad Ali al-Sabuni, and Abd al-Aziz ibn Baz have also referred to the hadiths attributed to the Prophet of Islam about the Mahdi and the savior of the end times in their books and speeches, and have considered these hadiths trustworthy because have been mentioned frequently by different narrators.[39][40][41]

According to Denise Spellberg, the concept of "Mahdism", although not one of the main Sunni beliefs, has been considered by Sunnis throughout history. In 1881, Muhammad Ahmad claimed to be the Mahdi in Sudan and started an uprising that was suppressed in 1898 by British forces. Belief in Mahdism spurred uprisings in the west and north of Africa in the nineteenth century. In 1849, a person named Bo Zian led an uprising in Algeria against the French tax system and the occupation of his country by the French under the name of Mahdi.[42]

Political Mahdism

[edit]Abdolkarim Soroush is one of the few thinkers who has analyzed the relationship between Mahdism and politics and presented a new perspective on Mahdism. He believes that political Mahdism has historically manifested itself in politics in at least four ways:[43][44][45][46]

- The theory of Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist: The theory of Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist, which is incompatible with democracy, is the child of political Mahdism. Political Mahdism justifies the special privileges of Faqīhs for government in the theory of Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist. Political Mahdism, based on the theory of Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist, presupposes the "supreme Faqīh" as the deputy of Muhammad al-Mahdi and gives the same authority to the "supreme Faqīh" in power and possession of the properties of the Muslims population, that the absent Imam has.

- The theory of monarchy on behalf of the Imam of the Safavid kings: Another form of political Mahdism throughout history that Abdolkarim Soroush refers to has been the theory of "monarchy on behalf of the Imam of the Safavid kings." This theory was in fact the political theory of the Safavids. This theory is also clearly in conflict with democracy.

- Hojjatieh's theory of political impracticality: Another form of political Mahdism mentioned by Abdolkarim Soroush is the theory of political impracticality during the absence and condemn all the governments before the emerge of the "Imam of Time" as usurper. Throughout history, many Shiite Faqīh have advocated this theory, and before the Islamic Revolution, this view was propagated by the Hojjatieh Association.

- The theory of revolutionary Islam or the "Waiting, a protest school": According to Abdolkarim Soroush, another form of Mahdism that is not very compatible with democracy is the theory of "Waiting, a protest school" by Dr. Ali Shariati. Shariati appears in the article "Waiting, a protest school" as a utopian and historian who believes in the determinism of history, who has a pragmatic approach to waiting for Mahdism to change the current status and achieve his desired utopia.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "درباره واژه مهدويت" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "شناخت معارف مهدوی ضرورت تردیدناپذیر عصر ماست - خبرگزاری مهر" (in Persian). 6 December 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "ظهور حضرت مسیح(ع) در عصر حضرت مهدی (ع) - خبرگزاری مهر" (in Persian). 25 December 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "یاران امام مهدی(عج) در زمان غیبت چه کسانی هستند؟ نقش خضر نبی(ع) در دوران غیبت - جهان نيوز" (in Persian). 17 December 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ رک: «معجم احادیث الامام المهدی»، ج7، مؤسسه معارف اسلامی، انتشارات مسجد مقدس جمکران، قم

- ^ سید هاشبم بحرانی «سیمای امام مهدی در قرآن»، ترجمه مهدی حائری قزوینی، نشر آفاق، تهران، 1374

- ^ سید محمد حسین طباطبایی، «تفسیر المیزان»، ج 14، ص 330، دفتر انتشارات اسلامی جامعه مدرسین حوزه علمیه قم، قم، چاپ پنجم، 1417 ه.ق

- ^ آلوسی، «روح المعانی فی تفسیر القرآن العظیم»، ج 9، ص 98، دارالکتب العلمیه، بیروت، چاپ اول، 1415 ه. ق

- ^ سید هاشم بحرانی، البرهان فی تفسیر القرآن، ج۴، ص ۲۵۴

- ^ شیخ طوسی، التبیان فی تفسیر القرآن، ج ۸، ص ۱۲۹

- ^ علی ابن ابراهیم، تفسیر قمی، ج ۲، ص ۱۳۴

- ^ طبرسی، مجمع البیان فی تفسیر القرآن، ج ۷، ص ۳۷

- ^ بحرانی، البرهان فی تفسیر القرآن، ج ۴، ص ۲۵۱

- ^ سبحانی، جعفر، الالهیات علی هدی الکتاب و السنه و العقل، المرکز العالمی للدراسات الاسلامیه، چاپ سوم، قم، ۱۴۱۲ ه. ق، ج ۴، ص ۱۳۲

- ^ طباطبایی، سید محمد حسین، دفتر انتشارات اسلامی جامعه مدرسین حوزه علمیه قم، چاپ پنجم، قم، ۱۴۱۷ ه. ق، ج ۱۵، ص ۱۵۵–۱۵۶

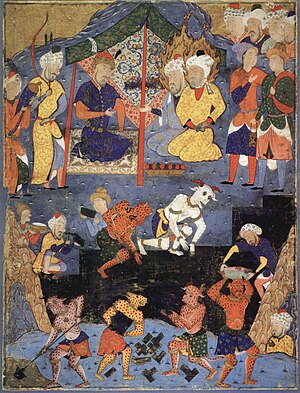

- ^ Chester Beatty Library. "Iskandar Oversees the Building of the Wall". image gallery. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ Amín, Haila Manteghí (2014). La Leyenda de Alejandro segn el Šāhnāme de Ferdowsī. La transmisión desde la versión griega hast ala versión persa (PDF) (Ph. D). Universidad de Alicante. p. 196 and Images 14, 15.

- ^ "زندگینامه حضرت مهدی(عج)" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "امام مهدی(ع) در کلام امام حسین(ع)" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ Kohlberg, Etan (1976). "From Imāmiyya to Ithnā-'ashariyya". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 39 (3). University of London: 521–534. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00050989. S2CID 155070530.

- ^ a b Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (2012). "Islam in Iran vii. The Concept of Mahdi in Twelver Shi'ism". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ^ "نواب خاص امام زمان چه کسانی هستند و چه ویژگی هایی دارند؟ - خبرگزاری مهر" (in Persian). 28 December 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "بررسی علمی در احادیث مهدی - آیت الله العظمی علامه سيد ابو الفضل ابن الرضا برقعى قمی" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "بررسی علمی در احادیث مهدی - نوار اسلام" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "نقدِ دیدگاه و عملکرد جریان "قرآنیان شیعه" - پایگاه اطلاع رسانی حوزه" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "کتابخانه الکترونیکی شیعه - منتخب الاثر فی الامام الثانی عشر علیه السلام" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "منتخب الاثر فی الامام ثانی عشر علیه السلام (دوره سه جلدی) - پاتوق کتاب فردا" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "مجموعه 4 جلدی "امامت و مهدویت" اثر آیتالله صافیگلپایگانی عرضه شد- تسنیم" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "سلسله مباحث امامت و مهدویت - کتابخانه دیجیتال قائمیه" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "زندگی، فعالیتها و دیدگاههای آیت الله صافی گلپایگانی - خبرگزاری مهر" (in Persian). 5 February 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "زندگی، فعالیت ها، افکار و تجربیات آیت الله العظمی صافی و شهید صدر - خبرگزاری حوزه" (in Persian). 18 February 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Aslan, Reza (2009). "Mahdi". In Juan Eduardo Campo (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (1st ed.). New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 447–448.

- ^ a b c d e Madelung, Wilferd. Encyclopedia of Islam "Al-Mahdi". Vol. 5. Brill. pp. 1230–1238.

- ^ مسند احمد، احمد بن حنبل، بیروت، دار صادر، ج 1، ص 337؛ ج 2، صص 22-27 به نقل از: جلوههای تشیع در مسند احمد، سیدکاظم طباطبایی، مطالعات اسلامی، بهار و تابستان، شماره 39 و 40، 1377، ص 52-53

- ^ کتاب طبقات الشافعیه (جلد 1) [چ1] -کتاب گیسوم (in Persian). Iḥsān. 2010. ISBN 9789643567910. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "جمع الجوامع" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ مجله درسهایی از مکتب اسلام، سال هشتم، شماره 6، اردیبهشت، 1346، ص 65

- ^ Islam: Religion, History, and Civilization. HarperOne. 2002. pp. 73–74.

- ^ دکتر عبدالمحسن بن حمد العباد، مجله الجامعه الاسلامیه، سال ۱۲، شماره ۲ (ربیعالثانی - جمادیالثانیه ۱۴۰۰ ق)، صفحه ۳۶۷، از «الرد علی من…»

- ^ شیخ محمد علی الصابونی، المهدی و اشراط الساعه، صفحه ۱۵ و ۱۸، مکتبة الغزالی، دمشق، چاپ اول، ۱۴۰۱ هجری قمری

- ^ مجله الجامعه الاسلامیه، سال اول، شماره ۳ (ذوالقعده ۱۳۸۸ ق)، صفحه ۴۲۹، از «إن الحق والصواب هو ما…»

- ^ Spellberg, Denise (2004). "Mahdi", Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa. Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ "مهدویت، غایت و کفایت از دموکراسی" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "تأسفی بر سخنان دکتر سروش" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "تحلیلی بر اساس اندیشه سروش ـ مهدویت و دموکراسی" (in Persian). Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "سیاست روز - نقدي بر مواضع عبدالكريم سروش" (in Persian). 23 July 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

External links

[edit]- Dictionary - definition of Mahdism

- Definition of Mahdist - followers of al-Mahdī

- Mahdism and Islamism in Sudan

- Millenarianism and Mahdism in Lebanon

- Mahdism: Islamic Messianism and the Belief in The Coming of the Universal Savior

- From Mahdism to Neo-Mahdism in the Sudan

- Islam: The Doctrine of Mahdism