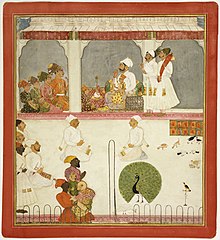

Ajit Singh of Marwar

| Ajit Singh Rathore | |

|---|---|

| Chatrapati Maharaja of Marwar | |

| |

| Ruler of Marwar | |

| Tenure | 19 February 1679 – 24 June 1724 |

| Predecessor | Maharaja Jaswant Singh |

| Successor | Maharaja Abhai Singh |

| Born | c. 19 February 1679 Lahore |

| Died | 24 June 1724 (aged 44–45) Meherangarh, Jodhpur |

| Issue | Abhai Singh Bakht Singh |

| Dynasty | House of Rathore |

| Father | Maharaja Jaswant Singh Rathore |

| Mother | Rani Jadav Jaskumvar |

| Religion | Hinduism |

Ajit Singh Rathore ( 19 February 1679 – 24 June 1724) was the ruler of Marwar region in the present-day Rajasthan and the son of Jaswant Singh Rathore.

Early life

[edit]Jaswant Singh of Marwar died at Jamrud in December 1678. His two wives were pregnant but, there being no living male heir, the lands in Marwar were converted by the emperor Aurangzeb into territories of the Mughal empire so that they could be managed as jagirs. He appointed Indra Singh Rathore, a nephew of Jaswant Singh, as ruler there.[1][a] Historian John F. Richards stresses that this was intended as a bureaucratic exercise rather than an annexation.[2]

There was opposition to Aurangzeb's actions because both pregnant women gave birth to sons during the time that he was enacting his decision. In June 1679, Durgadas Rathore, a senior officer of the former ruler[citation needed], led a delegation to Shahjahanabad where they pleaded with Aurangzeb to recognise the older of these two sons, Ajit Singh, as successor to Jaswant Singh and ruler of Marwar. Aurangzeb refused, offering instead to raise Ajit and to give him the title of raja, with an appropriate noble rank, when he attained adulthood. However, the offer was conditional on Ajit being brought up as a Muslim, which was anathema to the petitioners.[2][3]

The dispute escalated when Ajit Singh's younger brother died. Aurangzeb sent a force to capture the two queens and Ajit from the Rathore mansion in Shahjahanabad but his attempt was rebuffed by Durgadas Rathore, who initially used gunfire in retaliation and eventually escaped from the city to Jodhpur along with Ajit and the two queens, who were disguised as men. Some of those accompanying the escapees detached themselves from the party and were killed as they fought to slow down the pursuing Mughals.[2]

It is believed that the Dhaa Maa (wet nurse) of infant prince Ajit Singh of Marwar, Goora Dhaa put her beloved son on the royal bed instead of Ajit Singh and put the sleeping prince Ajit into a basket and smuggle him with others out of Delhi.[4][5][need quotation to verify] Others opine a slave girl with her infant posed as Rani and remained behind to be captured.[2] Aurangzeb deigned to accept this deceit and sent the child to be raised as a Muslim in his harem. Jadunath Sarkar mentioned that Aurangzeb brought up a milkman's son in his harem as Ajit Singh.[6] The child was renamed Mohammadi Raj and the act of changing religion meant that, by custom, the imposter lost all hereditary entitlement to the lands of Marwar that he would otherwise have had if he had indeed been Ajit Singh.[2][7]

Exile

[edit]Continuing to play along with the deceit, Aurangzeb refused to negotiate with representatives of Ajit Singh, claiming that child to be the imposter.[7] He sent his son, Muhammad Akbar, to occupy Marwar. Ajit Singh's mother convinced the Rana of Mewar, Raj Singh I, who is commonly thought to be her relative, to join in fighting against the Mughals.[8] Richards says that Raj Singh's fear that Mewar would also be invaded was a major motivation for becoming involved; another historian, Satish Chandra, thinks that there were several possible alternatives, including Singh seeing an opportunity to assert Mewar's position among the Rajput principalities of the region. The combined Rathore-Sisodia forces were no match for the Mughal army, Mewar was itself attacked and the Rajputs had to retire to the hills, from where they engaged in sporadic guerrilla warfare.[2][7][b]

For 20 years after this event, Marwar remained under the direct rule of a Mughal governor. During this period, Durgadas Rathore and Akheraj Singh Rajpurohit[9][10] (Rajguru of Ajit Singh) carried out a relentless struggle against the occupying forces. Trade routes that passed through the region were plundered by the guerrillas, who also looted various treasuries in present-day Rajasthan and Gujarat. These disorders adversely impacted the finances of the empire.

Aurangzeb died in 1707; he was to prove the last of the great Mughals. Durgadas Rathore and Akheraj Singh Rajpurohit[11][12] took advantage of the disturbances following this death to seize Jodhpur and eventually evict the occupying mughal force.[13]

Takes charge of Marwar

[edit]After consolidating his rule over Marwar, Ajit Singh grew increasingly bold as the Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah had marched south. He formed an alliance with Sawai Raja Jai Singh II of Amer and set upon capturing his ancestral lands which had been occupied by the Mughals. The Rajput kings started raiding Mughal camps and outposts, several towns and forts were captured, the biggest blow for the Mughals was however the capture of Sambhar which was an important Salt manufacturing site.[14]

In 1709 Ajit Singh made plans to conquer Ajmer and destroy the Muslim shrines and Mosques, however Jai Singh II was afraid that the destruction of Muslim shrines would lead to the wrath of the Mughal emperor after he had returned from the Deccan. Ajit Singh however ignored Jai Singhs advise and led his army towards Ajmer, ending the Rathore-Kachwaha alliance. Ajit Singh laid siege to Ajmer on 19 February, the Mughal garrison led by Shujaat Khan negotiated with Ajit Singh by offering him 45,000 rupees, 2 horses, an elephant and the holy town of Pushkar in exchange for sparing the shrine and the mosques. Ajit Singh agreed to the terms and returned to his capital.[15]

In June 1710 Bahadur Shah I marched to Ajmer with a large army and called Ajit Singh to Ajmer, he was joined by Jai Singh II. The rebellious Ajit Singh was finally pardoned and was formally accepted as the Raja of Jodhpur by the Mughal emperor.[16][17]

In 1712 Ajit Singh was given more power with his appointment as Mughal governor of Gujarat.[18]

Role in deposition of Farrukhsiyar

[edit]In 1713, the new Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar appointed Ajit Singh governor of Thatta. Ajit Singh refused to go to the impoverished province and Farrukhsiyar sent Husain Ali Braha to bring Ajit Singh into line, but also sent a private letter to Ajit Singh promising him blessings if he defeated Husain. Instead Ajit Singh chose to negotiate with Husain, accepting the governorship of Thatta with a promise for a return to Gujarat in the near future.[19] One of the other conditions of the peace agreement was the marriage of one of the daughters of the Jodhpur Raja with the Mughal emperor.

This gave him the time to prepare for war against the Mughals and on 1719 he invaded Delhi and captured it, and later executed Faruksiyar, bringing the Mughal Empire closer to its end. Rafi ud-Darajat was set on the throne as the new Mughal emperor.

Final days

[edit]

Ajit Singh kept on Suppressing the Mughals even after he executed Faruksiyar. As the new Mughal Emperor, Rafi-ud-Darajat rebelled against Ajit Singh and two major expeditions were sent against him, once under Sayyid Hussain Ali Khan and other under Iradatmand Khan. In 1721-22 Ajit Singh led an army and captured many parganas, he captured Mughal territory as far as Narnol and Mewat, which was 16 miles from the Mughal capital. In January 1723 he attacked the Mughal Governor of Ajmer and killed him, 25 Mughal officers were beheaded after the battle and their camp and baggage was looted.

Regarding his final days a lot of stories are there regarding Ajit Singh's death Persian sources indicate that it was his son Bakht Singh who assassinated Ajit Singh. Jadunath Sarkar believes that the Jodhpur court blamed the Jaipur raja because of their rivalry.[20]

The practice of sati was common among Rajput nobility in the region: 63 women accompanied Maharaja Ajit Singh onto the funeral pyre.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bhargava, Visheshwar Sarup (1966). Marwar and the Mughal Emperors. India: Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 121–122. ISBN 9788121504003.

- ^ a b c d e f Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-52156-603-2.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 189. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ^ Bose, Melia Belli. Royal Umbrellas of Stone: Memory, Politics, and Public Identity in Rajput Funerary Art. p. 175.

- ^ Gahlot, Jagdish Singh. Rajasthan: A Socio-economic Study. p. 4.

- ^ "History of Aurangzeb vol.3 : Sarkar, Jadunath". Internet Archive. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022., p334

- ^ a b c d Chandra, Satish (2005). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals. Vol. 2. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 309–310. ISBN 978-8-12411-066-9.

- ^ The Mertiyo Rathores of Merta, Rajasthan. Vol. II. p. 63.

- ^ Dr Prahalad Singh Rajpurohit,"Veer Kesari Singh Rajpurohit ka Jasprakash"

- ^ Sevaṛa, Prahalādasiṃha (2021). Rājapurohita jāti kā itihāsa (Dvitīya saṃsodhita saṃskaraṇa ed.). Jodhapura. ISBN 978-93-90179-06-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dr Prahalad Singh Rajpurohit,"Veer Kesari Singh Rajpurohit ka Jasprakash"

- ^ Sevaṛa, Prahalādasiṃha (2021). Rājapurohita jāti kā itihāsa (Dvitīya saṃsodhita saṃskaraṇa ed.). Jodhapura. ISBN 978-93-90179-06-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ N.S. Bhati, Studies in Marwar History, page 6

- ^ Thelen, Elizabeth M. (2018). Intersected Communities: Urban Histories of Rajasthan, c. 1500 – 1800 (PDF) (Thesis). University of California, Berkeley. Pg.37

- ^ Thelen, Elizabeth M. (2018). Intersected Communities: Urban Histories of Rajasthan, c. 1500 – 1800 (PDF) (Thesis). University of California, Berkeley. Pg.37-38

- ^ The Cambridge History of India, Volume 3 p. 322

- ^ Faruqui, Munis D. (2012). The Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504-1719. Cambridge University Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-1-107-02217-1.

- ^ Richards, The Mughal Empire, p. 262

- ^ Richards, The Mughals, p. 166

- ^ Sarkar, Jadunath (1994). A History of Jaipur: C. 1503–1938. Orient Blackswan. pp. 195–196. ISBN 9788125003335.

- ^ Major, Andrea (2010). Sovereignty and Social Reform in India: British Colonialism and the Campaign Against Sati, 1830-1860. Routledge. pp. 33, 127. ISBN 978-1-13690-115-7.

Notes

- ^ Some sources say that Indra Singh Rathore was a great-nephew of Jaswant Singh.[citation needed]

- ^ The relationship of Raj Singh I to Ajit Singh's mother is disputed. Historian Satish Chandra says that, although the claim is often made, they were unrelated.[7]

Citations

Further reading

[edit]- Gupta, R. K.; Bakshi, S. R., eds. (2008). Studies in Indian History: Rajasthan Through The Ages: The Heritage of Rajputs. Vol. 1. Sarup & Sons. ISBN 978-8-17625-841-8.