Oriental Stories

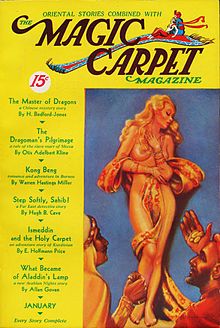

Cover of first issue (October/November 1930) | |

| Editor | Farnsworth Wright |

|---|---|

| First issue | October 1930 |

| Final issue | January 1934 |

| Company | Popular Fiction |

| Country | USA |

Oriental Stories, later retitled The Magic Carpet Magazine, was an American pulp magazine published by Popular Fiction Co., and edited by Farnsworth Wright. It was launched in 1930 under the title Oriental Stories as a companion to Popular Fiction's Weird Tales, and carried stories with far eastern settings, including some fantasy. Contributors included Robert E. Howard, Frank Owen, and E. Hoffman Price. The magazine was not successful, and in 1932 publication was paused after the Summer issue. It was relaunched in 1933 under the title The Magic Carpet Magazine, with an expanded editorial policy that now included any story set in an exotic location, including other planets.

Some science fiction began to appear alongside the fantasy and adventure material as a result, including work by Edmond Hamilton. Wright obtained stories from H. Bedford Jones, a popular pulp writer, as well as Edmond Hamilton and Seabury Quinn. Most of the covers of The Magic Carpet Magazine were by Margaret Brundage, including her first sale; Brundage later became well-known as a cover artist for Weird Tales. Competition from established pulps in the same niche, such as Adventure, was too strong, and after five issues under the new title the magazine ceased publication.

Publication history and contents

[edit]In 1923, J.C Henneberger and J.M. Lansinger's Rural Publishing Corporation launched Weird Tales, as a companion to their existing magazines, College Humor, The Magazine of Fun, and Detective Tales.[1] Weird Tales soon ran into financial trouble, and in late 1924 Henneberger and Lansinger split control of their stable of magazines: Henneberger incorporated Popular Fiction Co., took Weird Tales, and gave up the other titles, hiring Farnsworth Wright as editor.[2][3] Wright liked adventure and fantasy fiction with oriental settings, and printed some in Weird Tales, by writers such as Frank Owen.[4] In 1930 Henneberger and Wright decided to launch a companion magazine that specialized in oriental fiction.[2][3] The plans were in place by June 1930, when Wright wrote to Robert E. Howard, telling him about the new magazine, and asking him to submit stories.[5] Howard complied, and his "The Voice of El-Lil", about a lost city in Mesopotamia, appeared in the first issue, along with two stories by Frank Owen, and "The Man Who Limped" by Otis Adelbert Kline, the first in a series about a dragoman (interpreter) named Hamad the Attar. Other contributors included E. Hoffman Price, Frank Belknap Long, August Derleth, and David H. Keller; these were all known for fantasy, but Oriental Stories also published work by writers of non-fantasy adventures, including S.B.H. Hurst, James W. Bennett, and Warren Hastings. Frank Owen followed his story in the first issue with seven more over the next three years, including "Della Wu, Chinese Courtesan", in the third issue, described by magazine historian Mike Ashley as one of his best-known tales.[6]

The schedule was initially bimonthly, with a date of October/November 1930 on the cover of the first issue, but this only lasted for three issues before changing to quarterly, with the fourth issue dated Spring 1931.[6] The Spring 1932 issue contained Dorothy Quick's first sale to Wright, "Scented Gardens";[6] Quick sold one more story to Oriental Stories and many more to Weird Tales over the next two decades.[6][7] The cover of the Spring 1932 issue was Margaret Brundage's first sale.[6] Wright used Brundage's covers on every remaining issue of the magazine except for the July 1933 issue, which was by J. Allen St. John, a popular pulp artist.[8][9] Brundage went on to become one of Weird Tales' best-known cover artists of the 1930s.[6]

After the Summer 1932 issue there was a break in publication, while Wright planned to relaunch it. The next issue was dated January 1933, and the title was now The Magic Carpet Magazine. Wright had decided to broaden the editorial policy to include stories from any faraway places, including other planets; this meant the magazine was now a market for science fiction as well as fantasy and adventure stories. The second issue under the new title included Edmond Hamilton's "Kaldar, World of Antares", the first in a series similar to Edgar Rice Burroughs' stories of Mars.[6] Howard, a regular in Oriental Stories, continued to appear, with three more contributions; the last, "The Shadow of the Vulture", was the first story of his to feature Red Sonja, his female barbarian heroine.[10] More regulars from Weird Tales began to appear, including Seabury Quinn. The January 1933 issue included H. Bedford Jones' "Master of Dragons"; Jones was a very popular writer who wrote for higher-paying pulps, and Wright would have been delighted to secure a story from him, though Ashley suggests that since The Magic Carpet Magazine's rates were lower than Jones' usual markets, this was probably a story that had already been rejected by other magazines. Jones sold two more stories to Wright over the next year, but the magazine was not doing well financially. The "exotic adventure story" niche already had established pulp magazines such as Adventure, and The Magic Carpet Magazine did not have the resources to compete. The January 1934 issue was the last one. Material bought for the magazine by Wright was published in Weird Tales instead, including another Kaldar story by Edmond Hamilton.[6]

The magazine, under both titles, fetches high prices from collectors. Hulse considers the January 1934 issue likely to be the most expensive because it includes Howard's "Red Sonja" story, but a 2001 price guide to pulp collecting lists all issues at between $150 and $200, except for the first issue, October/November 1930, which is listed at $300.[10][11]

Bibliographic details

[edit]| Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 1930 | 1/1 | 1/2 | ||||||||||

| 1931 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 1/5 | 1/6 | |||||||

| 1932 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 | |||||||||

| 1933 | 3/1 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 3/4 | ||||||||

| 1934 | 4/1 | |||||||||||

| Issues of Oriental Stories, showing volume/issue number. Underlining indicates that an issue was titled as a quarterly (e.g. "Summer 1931") rather than as a monthly. From the January 1933 issue the title was changed to Magic Carpet. Farnsworth Wright was editor throughout.[12][6] | ||||||||||||

The magazine, under both titles, was published by Popular Fiction Co. of Chicago, and edited by Farnsworth Wright. It was in small pulp format; each issue of Oriental Stories was 144 pages, and priced at 25 cents. The page count dropped to 128 pages when the title changed to The Magic Carpet Magazine, and the price dropped to 15 cents; with the October 1933 issue the price went back up to 25 cents. The volume numbering was irregular; the first three volumes had six, three, and four issues, and there was a final volume of one issue. Oriental Stories maintained a bimonthly schedule for three issues, and then switched to quarterly; there was a hiatus when the title changed, and then The Magic Carpet Magazine stayed on a quarterly schedule throughout its run.[6][13]

Two anthologies collected fiction from Oriental Stories and The Magic Carpet Magazine:[6]

- Desmond, William (1975). Oriental Stories: Fascinating Tales of the East. Melrose Highlands, Massachusetts: Odyssey Publications. OCLC 56125660.

- Desmond, William (1977). The Magic Carpet Magazine. Melrose Highlands, Massachusetts: Odyssey Publications. OCLC 56128169.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Locke (2018), pp. 19-26.

- ^ a b Ashley (2000), p. 41.

- ^ a b Weinberg (1999a), pp. 3–4.

- ^ Ashley (1976), p. 34.

- ^ Burke (2007), p. 491.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ashley (1985), pp. 454-456.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (January 18, 2022). "Chronological List: Dorothy Quick". Galactic Central. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (January 18, 2022). "Artists: Brundage, Margaret (Johnson)". Galactic Central. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (January 18, 2022). "Contents Lists: Oriental Stories". Galactic Central. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Hulse (2013), pp. 211-212.

- ^ Cottrill (2001), p. 342.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (January 17, 2022). "Oriental Stories/Magic Carpet". Galactic Central. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (January 17, 2022). "Magazines, Listed by Title: Oriental Stories". Galactic Central. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Ashley, Michael (1976) [1974]. The History of the Science Fiction Magazine Volume 1: 1926-1935. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company. ISBN 0-8092-8003-5.

- Ashley, Mike (1985). "Oriental Stories". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 454–456. ISBN 978-0-313-21221-5.

- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines: The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-865-0.

- Burke, Rusty (2007). "A Short Biography of Robert E. Howard". The Best of Robert E. Howard, Volume One: Crimson Shadows. New York: Del Rey Books. pp. 485–496. ISBN 978-0-345-49018-6.

- Cottrill, Tim (2001). Bookery Fantasy's Ultimate Guide to the Pulps. Fairborn, Ohio: Bookery Press. OCLC 49312554.

- Hulse, Ed (2013). The Blood'n'Thunder Guide to Pulp Fiction. Murania Press. ISBN 978-1491010938.

- Locke, John (2018). The Thing's Incredible! The Secret Origins of Weird Tales. Elkhorn, California: Off-Trail Publications. ISBN 978-1-935-03125-3.

- Weinberg, Robert (1999a) [1977]. "A Brief History". In Weinberg, Robert (ed.). The Weird Tales Story. Berkeley Heights, New Jersey: Wildside Press. pp. 3–6. ISBN 1-58715-101-4.

External links

[edit] Media related to Oriental Stories at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Oriental Stories at Wikimedia Commons Works related to Oriental Stories at Wikisource

Works related to Oriental Stories at Wikisource

- Bimonthly magazines published in the United States

- Quarterly magazines published in the United States

- Defunct literary magazines published in the United States

- Fantasy fiction magazines

- Magazines established in 1930

- Magazines disestablished in 1934

- Defunct magazines published in Chicago

- Orientalism

- Pulp magazines

- Science fiction magazines established in the 1930s