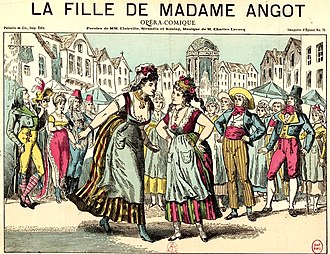

La fille de Madame Angot

La fille de Madame Angot (Madame Angot's Daughter) is an opéra comique in three acts by Charles Lecocq with words by Clairville, Paul Siraudin and Victor Koning. It was premiered in Brussels in December 1872 and soon became a success in Paris, London, New York and across continental Europe. Along with Robert Planquette's Les cloches de Corneville, La fille de Madame Angot was the most successful work of the French-language musical theatre in the last three decades of the 19th century, and outperformed other noted international hits such as H.M.S. Pinafore and Die Fledermaus.

The opera depicts the romantic exploits of Clairette, a young Parisian florist, engaged to one man but in love with another, and up against a richer and more powerful rival for the latter's attentions. Unlike some more risqué French comic operas of the era, the plot of La fille de Madame Angot proved exportable to more strait-laced countries without the need for extensive rewriting, and Lecocq's score was received with enthusiasm wherever it was played.

Although few other works by Lecocq have remained in the general operatic repertory, La fille de Madame Angot is still revived from time to time.

Background

[edit]During the Second Empire, Jacques Offenbach had dominated the sphere of comic opera in France, and Lecocq had struggled for recognition.[1] Defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 brought the Empire down, and Offenbach, who was inextricably associated in the public mind with it, became unpopular and went briefly into exile.[2] Lecocq's rise coincided with Offenbach's temporary eclipse. Before the war his only substantial success had been Fleur-de-Thé (Tea-flower) a three-act opéra-bouffe in 1868.[1] After moving to Brussels at the start of the war, Lecocq had two substantial successes there in a row. The first, the opérette Les cent vierges (The Hundred Virgins), ran for months at the Théâtre des Fantaisies-Parisiennes;[3] productions quickly followed in Paris, London, New York, Vienna and Berlin.[4] The success of this piece led Eugène Humbert, the director of the Brussels theatre, to commission another from Lecocq.[5]

Possibly at Humbert's suggestion,[n 1] Lecocq's librettists set the piece in Directory Paris in the later years of the French Revolution, an unfamiliar setting for a comic opera.[5] Their characters, though essentially fictional, incorporate elements of real people from the Revolutionary period. The régime was headed by Paul Barras, who does not appear in the opera but is an offstage presence. Mademoiselle Lange was a prominent actress and anti-government activist, but there is no evidence that the historical figure was Barras's mistress as she is in the opera.[5] There was a real activist called Ange Pitou (fictionalised in a novel by Dumas), but he had no known connection with Mlle. Lange. The black collars, used as a badge by the conspirators in the opera, are a reference to a song by the historical Pitou, "Les collets noirs".[8] The heroine's mother, Madame Angot – the formidable market woman with aspirations – is fictional, but was not the invention of the librettists, being a stock character in stage comedy of the Revolutionary period.[9][n 2]

First performances

[edit]The opera was first presented at the Fantaisies-Parisiennes on 4 December 1872, and ran for more than 500 performances.[6] In Paris, where it opened on 21 February 1873 at the Théâtre des Folies-Dramatiques, it enjoyed a run of 411 performances,[11] and set box-office records for the receipts.[n 3] Productions quickly followed in theatres throughout France: within a year of the opening of the Paris production, the work was given in 103 French cities and towns.[5]

Original cast

[edit]

| Role | Voice type | Premiere Cast, 4 December 1872 (Conductor: Warnotz) |

|---|---|---|

| Mademoiselle Lange, actress and favourite of Barras | mezzo-soprano | Marie Desclauzas |

| Clairette Angot, betrothed to Pomponnet | soprano | Pauline Luigini |

| Larivaudière, friend of Barras, conspiring against the Republic | baritone | Charlieu/Chambéry |

| Pomponnet, barber of the market and hairdresser of Mlle Lange | tenor | Alfred Jolly |

| Ange Pitou, a poet in love with Clairette | tenor | Mario Widmer |

| Louchard, police officer at the orders of Larivaudière | bass | Jacques Ernotte |

| Amarante, market woman | mezzo-soprano | Jane Delorme |

| Javotte, market woman | mezzo-soprano | Giulietta Borghese (Juliette Euphrosine Bourgeois) |

| Hersillie, a servant of Mlle. Lange | soprano | Camille |

| Trenitz, dandy of the period, officer of the Hussars | tenor | Touzé |

| Babet, Clairette's servant | soprano | Pauline |

| Cadet | baritone | Noé |

| Guillaume, market man | tenor | Ometz |

| Buteaux, market man | bass | Durieux |

Synopsis

[edit]Act 1

[edit]The scene of the opera is Directoire Paris, 1794; the Reign of Terror is over, but Paris is still a dangerous place for opponents of the government. The heroine is a charming young florist called Clairette. She is the daughter of Madame Angot, a former market woman of Les Halles, who was famous for her beauty, her amorous adventures and her sharp tongue. She died when Clairette was three, and the child was brought up by multiple adoptive parents from Les Halles, and given a fine education at a prestigious school.

A marriage with Pomponnet, a sweet and gentle hairdresser, has been arranged for her against her wishes, for she is in love with Ange Pitou, a dashing poet and political activist, who is continually in trouble with the authorities. His latest song lyric, "Jadis les rois", satirises the relations between Mlle. Lange – an actress and the mistress of Barras – and Barras's supposed friend Larivaudière. The latter has paid Pitou to suppress the song but Clairette gets hold it and, to avoid her marriage with Pomponnet, sings it publicly and is, as she expects, arrested so that her wedding is unavoidably postponed.

Act 2

[edit]Lange summons the girl to learn the reason for her attack and is surprised to recognise her as an old schoolfriend. Pomponnet loudly protests Clairette's innocence and says that Ange Pitou is the author of the verses. Lange already knows of Pitou and is not unmindful of his charms. He has been invited to her presence and arrives while Clairette is there and the interview is marked with more than cordiality. The jealous Larivaudière appears meanwhile and, to clear herself, Lange declares that Pitou and Clairette are lovers and have come to the house to join in a meeting of anti-government conspirators to be held at midnight. Clairette discovers that she does not enjoy a monopoly of Pitou's affections, and that he is dallying with Lange.

The conspirators arrive in due time, but in the middle of proceedings, the house is surrounded by Hussars; Lange hides the badges of the conspirators, "collars black and tawny wigs", and the affair takes on the appearance of nothing more dangerous than a ball. The Hussars join gaily in the dance.

Act 3

[edit]To avenge herself, Clairette invites all of Les Halles to a ball, to which she lures Lange and Pitou by writing each a forged letter, seemingly signed by the other. At the ball Pitou and Lange are unmasked, Larivaudière is enraged, but realises he must hush matters up to save Barras from scandal. After a lively duet in which the two young women quarrel vigorously there is a general mêlée, ended by Clairette who extends a hand to her friend and declares that she truly prefers the faithful Pomponnet to the fickle Pitou. Remembering Madame Angot's amorous flights, Pitou remains hopeful that Clairette will take after her mother and may one day be interested in him again.

- Source: Gänzl's Book of the Musical Theatre.[13]

Numbers

[edit]In The Encyclopedia of Musical Theatre (2001), Kurt Gänzl describes Lecocq's score as "a non-stop run of winning numbers". He singles out in Act 1 Clairette's "sweetly grateful romance 'Je vous dois tout'"; Amaranthe's "Légende de la mère Angot: 'Marchande de marée'"; Pitou's "Certainement, j'aimais Clairette"; and the politically dangerous "Jadis les rois, race proscrite". Act 2 highlights include Lange's virtuoso "Les Soldats d'Augereau sont des hommes"; Pomponnet's "Elle est tellement innocente"; the duet of the old schoolfriends "Jours fortunés de notre enfance"; the encounter of Lange and Pitou "Voyons, Monsieur, raisonnons politique"; the whispered "Conspirators' Chorus"; and the waltz "Tournez, Tournez" that concludes the Act. From Act 3 Gänzl makes particular mention of the "Duo des deux forts"; the "Letter duet 'Cher ennemi que je devrais haïr'"; and the "Quarrel Duet 'C'est donc toi, Madam' Barras'".[6]

Act 1

- Overture

- Chorus and Scène – "Bras dessus, bras dessous" – (Arm in arm)

- Couplets (Pomponnet) – "Aujourd'hui prenons bien garde" – (Today let's take good care)

- Entrée de la Mariée – "Beauté, grâce et décence" – (Beauty, grace and dignity)

- Romance (Clairette) – "Je vous dois tout" – (I owe you all)

- Légende de la Mère Angot – "Marchande de Marée" – (A sea trader)

- Rondeau (Ange Pitou) – "Très-jolie" – (Very pretty)

- Duo (Clairette and Pitou) – "Certainement j'aimais Clairette" – (Certainly I love Clairette)

- Duo bouffe (Pitou and Larivaudière) – "Pour être fort on se rassemble" – (To be strong, let's gather together)

- Finale – "Eh quoi! c'est Larivaudière" – (What! It's Larivaudière)

- Chorus – "Tu l'as promis" – (You have promised)

- Chanson Politique (Clairette) – "Jadis les rois" – (Before the kings)

- Strette – "Quoi, la laisserons nous prendre" – (What! Let our child be taken!)

Act 2

- Entr'acte

- Chorus of Merveilleuses – "Non, personne ne voudra croire" – (No-one would believe it)

- Couplets (Lange and chorus) – "Les soldats d Augereau sont des hommes" – (Augereau's soldiers are men)

- Romance (Pomponnet) – "Elle est tellement innocente" – (She is so innocent)

- Duo (Clairette and Lange) – "Jours fortunés" – (Lucky days)

- Couplets (Lange and Pitou) – "La République à maints défauts" – (The republic has many faults)

- Quintette (Clairette, Larivaudière, Lange, Pitou, Louchardj) – "Hein, quoi!" – (Hah! What!)

- Chorus of conspirateurs – "Quand on conspire" – (When we conspire)

- Scène – "Ah! je te trouve" – (Ah, I have found you)

- Valse – "Tournez, tournez, qu'a la valse" – (Turn, turn, waltz!)

Act 3

- Entr'acte

- Chorus – "Place, place." – (Places, places!)

- Couplets (Clairette) – "Vous aviez fait de la dépense" – (You paid the cost)

- Sortie – "De la mère Angot" – (Of Mother Angot)

- Duo des deux forts (Pomponnet and Larivaudière) – "Prenez donc garde !" – (Take care!)

- Trio (Clairette, Pitou and Larivaudière) – "Je trouve mon futur" – (I find my future)

- Duo des lettres (Lange and Pitou) – "Cher ennemi" – (Dear enemy)

- Couplets de la dispute (Clairette and Lange) and Ensemble – "Ah! c'est donc toi" – (Ah, so it's you)

Reception

[edit]Gänzl writes that together with Robert Planquette's Les cloches de Corneville, La fille de Madame Angot was "the most successful product of the French-language musical stage" in the last three decades of the 19th century. He adds, "Even such pieces as H.M.S. Pinafore and Die Fledermaus, vastly successful though they were in their original languages, did not have the enormous international careers of Lecocq's opéra-comique".[6]

The reviewer in La Comédie wrote of the original Brussels production, "It is a long time since we saw at the theatre a better piece; it is interesting, perfectly proper, and crisp."[14] The Paris correspondent of The Daily Telegraph also commented on the propriety of the piece, and remarked that its enormous success with a public used to broader entertainments at the Folies-Dramatiques was "the most eloquent possible tribute to the intrinsic beauty of the music".[15] In Le Figaro the reviewer reported "frenzied bravos" and numerous encores, and praised the music: "a succession of memorable songs, lively, falling easily on the ear, and certain to appeal to the lazy ear of a French audience." The critic judged that Lecocq's score approached, but rarely fell into, vulgarity, and contained strong contrasts to fit the characters and situations. He had reservations about the singers, noting but not wholly sharing the audience's enthusiasm for the two leading ladies.[16]

In Vienna, Eduard Hanslick praised the freshness of the music and congratulated the composer on having an unusually good libretto to work with. He considered Lecocq inferior to Offenbach in invention and originality, but superior in musical technique.[17] The Musical World praised the "dash and style" of the work, but thought the score less elevated in musical style than Fleur de thé and Les cent vierges.[7] The Athenaeum took a different view on the latter point, regarding the piece as in the true tradition of French opéra comique, as practised by Boieldieu, Hérold, Auber and Adam, rather than the less refined manner of Hervé and Offenbach.[18]

Revivals and adaptations

[edit]For fifty years after the premiere La fille de Madame Angot was revived continually in Paris.[5] Among the higher-profile productions were those at the Éden-Théâtre (1888), Théâtre des Variétés (1889) and Théâtre de la Gaîté (1898). The work finally entered the repertoire of the Opéra Comique in the 1918–1919 season, and remained there until after the Second World War. A 1984 revival was mounted in Paris at the Théâtre du Châtelet.[5] The work continues to be seen from time to time in the French provinces. Operabase gives details of a 2018 production at the Odéon in Marseille.[19]

Humbert successfully took the Brussels production to London in May 1873, after which managements there hastened to mount English translations of the piece: three different productions played in London in 1873, three more the following year and five in 1875. Some of Britain's leading theatrical figures were involved: H. J. Byron, H. B. Farnie and Frank Desprez all made adaptations of the text, and London stars including Selina Dolaro, Emily Soldene, Harriet Everard, Fred Sullivan, Richard Temple and Pauline Rita appeared in one or more of the productions.[20] In an 1893 revival at the Criterion Theatre, the cast included Decima Moore, Amy Augarde, Courtice Pounds and Sydney Valentine.[21] By the turn of the century, British revivals had become few, and the last London production recorded by Gänzl and Lamb was at Drury Lane in 1919 during Sir Thomas Beecham's opera season.[20][22]

In New York, as in London, the first production (August 1873) was given in the original by a French company. An English version followed within weeks. Another French production was staged in 1879, and the last revival in English recorded by Gänzl and Lamb was in August 1890.[20] Oscar Hammerstein I mounted a production in French at the Manhattan Opera House as part of a season of opéra comique in 1909.[23]

Productions were staged in translation in Germany (Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater, Berlin, November 1873); Austria (Carltheater, Vienna, January 1874); Australia (Opera House, Melbourne, September 1874); and Hungary (State Theatre, Kolozsvár, March 1875). The piece was also translated for productions in Russian, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Swedish, Turkish, Polish, Danish and Czech.[6]

In the later decades of the 20th century, the music of La fille de Madame Angot became familiar to audiences in the US, Britain and Australia arranged as a ballet score for Léonide Massine. The first version of the ballet was given under the title Mademoiselle Angot in New York in 1943. Lecocq's music was arranged by Efrem Kurtz and Richard Mohaupt.[24] Massine created a new version of the work for Sadler's Wells Ballet in 1947, as Mam'zelle Angot, with a new score arranged from Lecocq's original by Gordon Jacob. The plot of the ballet follows that of the opera fairly closely.[25]

Notes, references and sources

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Another version of the genesis of the piece is that Koning suggested writing a new piece for Brussels, Siraudin had the idea of using Madame Angot as a theme and the libretto was then written by Clairville, although the other two were credited as co-authors.[6] A third version, current in the decade after the premiere, was that Lecocq and his collaborators unsuccessfully offered the piece to four managements in Paris – the Opéra Comique, the Variétés, the Bouffes-Parisiens and the Folies-Dramatiques – before turning to Brussels to have the work staged.[7]

- ^ When the opera was first performed in non-Francophone countries the name Madame Angot meant nothing to the public: in London, critics remarked that in France the name was as well known as Nell Gwynne or Mrs Gamp was to British audiences.[10]

- ^ A list of the gross takings of all stage productions in Paris during the two decades from 1870, published in 1891, showed La fille de Madame Angot as the most successful opera by any composer in that time, earning more than two million francs (about €8,826,363 in 2015 purchasing values).[12]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Andrew Lamb. "Lecocq, (Alexandre) Charles", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 September 2018 (subscription required)

- ^ Faris, p. 164; and Yon, p. 396

- ^ Kenrick, John "Stage Musical Chronology, 1870 to 1874", Musicals101. Retrieved 28 October 2018

- ^ Gänzl and Lamb, pp. 330–331

- ^ a b c d e f Pourvoyeur, Robert. "La fille de Madame Angot", Opérette – Théâtre Musical, Académie Nationale de l'Opérette. Retrieved 28 October 2018

- ^ a b c d e Gänzl, pp. 644–647

- ^ a b "Charles Lecocq", The Musical World, 10 December 1881, p. 797

- ^ Amann, p. 122

- ^ Lyons, p. 136

- ^ "The Drama in Paris", The Era , 2 March 1873, p. 10; and "La fille de Madame Angot", The Pall Mall Gazette, 30 October 1873, p. 11

- ^ "Le succès au théâtre", Le Figaro, 23 August 1891, p. 2

- ^ "The Drama in Paris", The Era, 29 August 1891, p. 9; and Conversion, Historical currency converter. Retrieved 28 October 2018

- ^ Gänzl and Lamb, pp. 337–341

- ^ "Lyrical novelties at Brussels", The Musical World, 8 February 1873, p. 76

- ^ "La fille de Mdme. Angot", The Musical World, 22 March 1873, p. 184

- ^ Bénédict. "Chronique musicale", Le Figaro, 23 February 1873, p. 3

- ^ Hanslick, Eduard. "Serious and buffo opera in Vienna", The Musical World, 15 December 1877, p. 836

- ^ "La fille de Madame Angot", The Athenaeum, 24 May 1873, pp. 670–671

- ^ "Performance search", Operabase. Retrieved 29 October 2018

- ^ a b c Gänzl and Lamb, pp. 335–337

- ^ Shaw, vol. 2, pp. 941–948

- ^ "The Daughter of Madame Angot", The Musical Times, August 1919, p. 425

- ^ "Light Opera Starts at the Manhattan", The New York Times, 17 November 1909, p. 12

- ^ "Mademoiselle Angot", American Ballet Theatre. Retrieved 30 October 2018

- ^ Craine and Mackrell, p. 291; and Royal Opera House programme, 23 February 1980

Sources

[edit]- Amann, Elizabeth (2015). Dandyism in the Age of Revolution. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-18725-9.

- Craine, Debra; Judith Mackrell (2010). The Oxford Dictionary of Dance (second ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956344-9.

The Oxford Dictionary of Dance.

- Faris, Alexander (1980). Jacques Offenbach. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-11147-3.

- Gänzl, Kurt (2001). The encyclopedia of the musical theatre, Volume 1 (second ed.). New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 978-0-02-865572-7.

- Gänzl, Kurt; Andrew Lamb (1988). Gänzl's Book of the Musical Theatre. London: The Bodley Head. OCLC 966051934.

- Lyons, Martyn; Malcolm Lyons (1975). France Under the Directory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09950-9.

- Shaw, George Bernard (1981). Shaw's Music: The Complete Musical Criticism in Three Volumes. Dodd, Mead. ISBN 978-0-396-07967-5.

- Yon, Jean-Claude (2000). Jacques Offenbach (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-074775-7.