Macau Incident (1799)

| Macau Incident | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

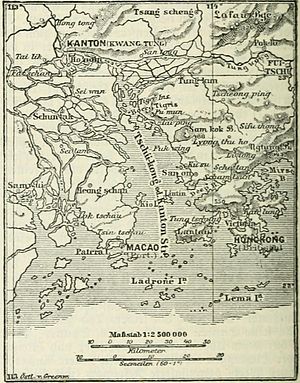

Map of the mouth of the Pearl River. The Wanshan Archipelago labelled "Ladrone In". | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Captain William Hargood | Rear-Admiral Ignacio Maria de Álava | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Two ships of the line, one frigate | Two ships of the line, four frigates | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | None | ||||||

The Macau Incident was an inconclusive encounter between a powerful squadron of French and Spanish warships and a British Royal Navy escort squadron in the Wanshan Archipelago (or Ladrones Archipelago) off Macau on 27 January 1799. The incident took place in the context of the East Indies campaign of the French Revolutionary Wars, the allied squadron attempting to disrupt a valuable British merchant convoy due to sail from Qing Dynasty China. This was the second such attempt in three years; at the Bali Strait Incident of 1797 a French frigate squadron had declined to engage six East Indiamen on their way to China. By early 1799, the French squadron had dispersed, with two remaining ships deployed to the Spanish Philippines. There the frigates had united with the Spanish Manila squadron and sailed to attack the British China convoy gathering at Macau.

The British commander in the East Indies, Rear-Admiral Peter Rainier was concerned about the vulnerability of the China convoy and sent reinforcements to support the lone Royal Navy escort, the ship of the line HMS Intrepid under Captain William Hargood. These reinforcements arrived on 21 January, only six days before the allied squadron arrived off Macau. Despite being outnumbered in ships and guns, Hargood sailed to meet the French and Spanish ships, and a chase ensued through the Wanshan Archipelago before contact was lost. Both sides subsequently claimed that the other had refused battle, although it was the allied squadron which withdrew, Hargood later successfully escorting the China convoy safely westwards.[1]

Background

[edit]The East Indian trade was an essential component of the economy of Great Britain in the eighteenth century. Administered by the East India Company from British India, exotic trade goods were carried on large, well-armed merchant ships known as East Indiamen,[2] which weighed between 500 and 1,200 long tons (510 and 1,220 t).[3] Among the most valuable parts of the East India trade was an annual convoy from Canton, a port in Qing Dynasty China. Early each year, a large convoy of East Indiamen would assemble at Whampoa Anchorage in preparation for their six-month journey across the Indian Ocean and through the Atlantic to Britain. The value of the trade carried in this convoy, nicknamed the "China Fleet", was enormous: one convoy in 1804 was reported to be carrying goods worth over £8 million in contemporary values (the equivalent of £900,000,000 as of 2024).[4][5]

British interests in the East Indies were protected by a large but scattered Royal Navy squadron under the overall command of Rear-Admiral Peter Rainier. By 1799, Rainier's command covered many thousands of square miles of ocean, including the strategically important ports of British India, Bombay, Madras and Calcutta and the coast of British Ceylon, as well as bases in the Red Sea, at Penang and in the Dutch East Indies. He also had to maintain a watch on hostile warships, particularly a French force at the remote island base of Île de France (now Mauritius), the Dutch at Batavia (now Djakarta) and the Spanish at Manila.[6] The French had been the greatest threat, with a powerful squadron assembled in 1796 under Contre-amiral Pierre César Charles de Sercey menacing British shipping in the East Indies in 1796 and 1797. On 28 January 1797, Sercey's force intercepted six East Indiamen in the Bali Strait on their way to China. In the ensuing Bali Strait Incident only quick thinking by Commodore James Farquharson in Alfred saved the Indiamen. In the poor visibility, the Indiamen imitated Royal Navy warships and dissuaded Sercey from pressing his attack.[7]

Sercey's force had subsequently broken up as it proved too expensive to maintain as a cohesive force. By late 1798, Sercey was at anchor in Batavia with only two vessels, the 20-gun corvette Brûle-Gueule and the 40-gun frigate Preneuse, which had arrived in Batavia from a diplomatic mission to the Kingdom of Mysore in a state of near-mutiny; Captain Jean-Matthieu-Adrien Lhermitte had executed five men for disobedience en route.[8] Sercey also learned that two additional frigates, Forte and Prudente would not be joining him: his orders had been countermanded by Governor Malartic on Île de France and these frigates were now cruising independently against British trade in the Indian Ocean.[9] Sercey decided to augment his forces by uniting them with the allied Spanish squadron at Manila in the Spanish Philippines, his frigates arriving on 16 October 1798, although the admiral remained at Surabaya.[a] The Spanish squadron had been severely damaged in a typhoon of April 1797 and repairs had taken nearly two years: when British frigates raided Manila in January 1798 not one Spanish ship was in a condition to oppose them.[12]

Incident at Macau

[edit]News of the junction of the French and Spanish squadrons reached Rainier soon afterwards. With the assembling merchant ships at Macau were the frigates HMS Fox and HMS Carysfort and the 64-gun ship of the line HMS Intrepid, the escort commanded by Captain William Hargood. However Fox and Carysfort were detached with a local convoy in November 1798,[13] and Rainier, whose forces were largely committed to the Red Sea following the recent French invasion of Egypt, gave urgent orders for the frigates to be replaced by the 38-gun HMS Virginie and 74-gun HMS Arrogant.[14] The reinforcements sailed through the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea, arriving at Macau on 21 January 1799.[6]

The Franco-Spanish squadron, comprising the 74-gun ships of the line Europa and Montañés, and the frigates Santa María de la Cabeza and Santa Lucía, accompanied by Preneuse and Brûle-Gueule, sailed from Manila on 6 January 1799, under the command of Rear-Admiral Ignacio Maria de Álava.[15] Alava's squadron crossed the South China Sea in three weeks, arriving in the Wanshan Archipelago near Macau on 27 January 1799 with the intention of attacking shipping at Macau and in the mouth of the Pearl River. Alava had been informed of the presence of Intrepid by Danish merchants but was unaware of the arrival of Rainier's reinforcements.[16]

Hargood immediately sailed to confront Alava, both squadrons initially forming lines of battle and steering towards one another, Virginie at the head of the British line.[10] What followed has been the subject of dispute. Hargood reported that the Franco-Spanish squadron then turned and fled into the Wanshan Archipelago, where they anchored as darkness fell before withdrawing before dawn. He ascribes this to "their dread of a conflict that would in all probability have terminated in their disgrace".[15] Alava however reported in the Manila Gazette that it was Hargood who had retreated into the Wanshan Archipelago, pursued closely by Europa. Alava claimed that he would have pressed the attack but for damage to the rigging on Montañés that allowed Hargood to escape. He does not explain why his squadron then withdrew without attacking the apparently unprotected assembled China Fleet anchored in Macau.[15]

Aftermath

[edit]In historian C. Northcote Parkinson's assessment "It is perhaps fair to conclude that neither squadron was spoiling for a fight", although he describes Lhermitte's subsequent reaction as "disgust" and Sercey's as "fury".[16][11] Richard Woodman considered that by this action the French threw "away at a stroke the chance not only of seizing a valuable convoy, but of establishing Franco-Spanish dominance in Indo-Chinese waters".[14] Alava retired to Manila, the French ships departing for Batavia and subsequently returning to Île de France. There Preneuse was intercepted at the action of 11 December 1799 by a blockade squadron made up of HMS Tremendous and HMS Adamant, driven on shore and destroyed. Sercey subsequently returned to France, retired from the French Navy and became a planter on Île de France.[17]

Hargood sailed from Macau with the China Fleet on 7 February, passing unimpeded into the Indian Ocean. Alava did belatedly send Europa and frigate Fama back to Macau in May, but this achieved nothing.[16] Rainier ensured that the 1800 China Fleet was well defended, but no further attacks were made on British shipping from China before the Peace of Amiens in 1802.[16] Early in the Napoleonic Wars, in 1804, a powerful French squadron attacked the China Fleet at the Battle of Pulo Aura, but the East Indiamen succeeded in bluffing the French into withdrawing after a brief exchange of fire.[7]

Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Allen, Joseph (1841). Memoir of the Life and Services of Admiral Sir William Hargood. Greenwich, England: H. S. Richardson. pp. 94–95. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ Woodman 2001, p. 101.

- ^ Clowes 1997, p. 337.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Woodman 2001, p. 32.

- ^ a b Woodman 2001b, p. 160.

- ^ a b James 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Parkinson 1954, p. 123.

- ^ Parkinson 1954, p. =123.

- ^ a b Woodman 2001a, p. 115.

- ^ a b Parkinson 1954, p. 124.

- ^ Henderson 1994, p. 49.

- ^ Parkinson 1954, p. 156.

- ^ a b Woodman 2001, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Parkinson 1954, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d Parkinson 1954, p. 158.

- ^ Parkinson 1954, p. 131.

References

[edit]- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900. Vol. V. London: Chatham. ISBN 1-86176-014-0.

- Henderson, James (1994) [1970]. The Frigates. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-432-6.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, 1797–1799. Vol. II. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-906-9.

- McGrigor, Mary (2004). Defiant and Dismasted at Trafalgar: The Life and Times of Admiral Sir William Hargood. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781844150342.

- Parkinson, C. Northcote (1954). War in the Eastern Seas, 1793–1815. London: George Allen & Unwin. OCLC 460032956.

- Woodman, Richard (2001b) [1996]. Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Nelson Against Napoleon: from the Nile to Copenhagen, 1798–1801. London: Chatham and the National Maritime Museum, Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-86176-026-4.

- Woodman, Richard (2001) [1998]. Gardiner, Robert (ed.). The Victory of Seapower. London, England: Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

- Woodman, Richard (2001a). The Sea Warriors: Fighting Captains and Frigate Warfare in the Age of Nelson. London: Constable. ISBN 1-84119-183-3.

- Battles and conflicts without fatalities

- Conflicts in 1799

- History of the South China Sea

- Military history of Macau

- Naval battles of the French Revolutionary Wars involving France

- Naval battles of the French Revolutionary Wars involving Great Britain

- Naval battles of the French Revolutionary Wars involving Spain

- Wanshan Archipelago