Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau

Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 20 July 1700 |

| Died | 13 August 1782 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | French |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany |

Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau (French pronunciation: [ɑ̃ʁi lwi dyamɛl dy mɔ̃so]; 20 July 1700 – 13 August 1782) was a French physician, naval engineer and botanist.[1] The standard author abbreviation Duhamel is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[2]

Biography

[edit]Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau was born in Paris in 1700, the son of Alexandre Duhamel, lord of Denainvilliers. In his youth he developed a passion for botany, but at his father's wish he studied law from 1718 to 1721.

After inheriting his father's large estate, he expanded it into a model farm, where he developed and tested new methods of horticulture, agriculture and forestry. The results of this work, he published in numerous publications. Commission by the French Academy of Sciences in 1728 Duhamel investigate the saffron cultivation in Gâtinais. In the following years continued to investigate physiological problems of crops. He also investigated growth of the trees in cooperation with Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon. From 1740 he also started focusing on meteorological problems, in particular their impact on agricultural production.

In 1738 he was elected to the French Academy of Sciences, and served three times as its president. He was appointed Inspector-General of the Marine in 1739, and made scientific studies of shipbuilding, the conservation of wood, the paramedical and fair of sailors, etc. In 1741 he co-founded a school of Marine science, which in 1765 became the Ecole des Ingénieurs-Constructeurs, the forerunner of the modern Ecole du Génie Maritime. He was also involved in the foundation of the "Académie de marine de Brest", on 31 July 1752.

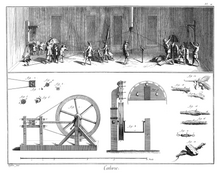

Following the work of Réaumur, in 1757 he released the Description des Arts et Métiers and opposed the writers of the Encyclopédie. His fondness for concrete problems, experimentation and popularization made him one of the forerunners of modern agronomy and silviculture.

In 1767, du Monceau was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. He died in Paris on 13 August 1782.

Work

[edit]

Horticultural experiments in plant physiology

[edit]Having been requested by the French Academy of Sciences to investigate a disease which was destroying the saffron plant in Gâtinais, he discovered the cause in a parasitical fungus which attached itself to the roots. This achievement gained him admission to the French Academy of Sciences in 1738. From then on until his death he busied himself chiefly with making experiments in plant physiology.[3]

Having learned from Sir Hans Sloane that madder possesses the property of giving colour to the bones, he fed animals successively on food mixed and unmixed with madder; and he found that their bones in general exhibited concentric strata of red and white, while the softer parts showed in the meantime signs of having been progressively extended.[3]

From a number of experiments he was led to believe himself able to explain the growth of bones, and to demonstrate a parallel between the manner of their growth and that of trees. Along with the naturalist Buffon, he made numerous experiments on the growth and strength of wood, and experimented also on the growth of the mistletoe, on layer planting, on smut in corn, and others. He was probably the first, in 1736, to distinguish clearly between the alkalis, potash and soda.[3] His works on trees and forestry were translated into German by Carl Christoph Oelhafen von Schoellenbach.[4]

Meteorological observations

[edit]From the year 1740 on he made meteorological observations, and kept records of the influence of the weather on agricultural production. For many years he was inspector-general of the marine, and applied his scientific experience to the improvement of naval construction.[3]

About the division of labour

[edit]In his additions to l'Art de l'Épinglier (The Art of the Pin-Maker, 1761), Henri Louis Duhamel du Monceau wrote about the "division of labour":

- There is nobody who is not surprised of the small price of pins; but we shall be even more surprised, when we know how many different operations, most of them very delicate, are mandatory to make a good pin. We are going to go through these operations in a few words to stimulate the curiosity to know their detail; this enumeration will supply as many articles which will make the division of this labour... The first operation is to have brass go through the drawing plate to calibrate it.

This text is believed to have inspired Adam Smith for his famous work An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations published in 1776.

Criticism by the Encyclopedists

[edit]

Following the work of René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, in 1757 Duhamel released the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers and opposed the writers of the Encyclopédie. The Encyclopédistes didn't take this well, and criticised him on occasion. For example, Denis Diderot (1767) recalled:

- This Duhamel has invented an infinity of machines which serve no purpose, has written and translated a multitude of books on agriculture, of which it is not known if they have any useful result, that is still awaited.[5]

- - Denis Diderot, 1767.

Diderot seems to forget his debt to Duhamel du Monceau for the Encyclopédie, including the articles "Agriculture," "Rope," "Pipe" and "Sugar."

The succession of Jean-Paul Grandjean de Fouchy, perpetual secretary of the Academy of Sciences, clash sees supporters of Condorcet, led by d'Alembert, and those of the astronomer Bailly, led by Count de Buffon. In 1773, the appointment of Condorcet as deputy Grandjean de Fouchy sees the triumph of the party of the philosophers against the use of naval officers linked to Duhamel.

But in January 1775, supporters of Bailly, including Patrick D'Arcy and Jean-Charles de Borda, both naval officers make up a commission to monitor the work of the Secretary, that Condorcet considered censorship. To be elected, he must give up the pension ECU 1000 and submit an application in proper form to respect the rules of Académie2. Condorcet would later refer to this episode:

- "Though he loved many innovations in science and devoted his life to introduce useful ones in the arts, he didn't like them in politics and even less in the statutes of the academies"

- - Marquis de Condorcet, 1783[6]

Memory

[edit]Asteroid 100231 Monceau, discovered by astronomer Eric Walter Elst at the La Silla Observatory in 1994, was named in his memory.[1] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 22 July 2013 (M.P.C. 84381).[7]

Selected publications

[edit]

His works are nearly ninety in number and include many technical handbooks. The principal are:

- Traité de la fabrique des manœuvres pour les vaisseaux, ou l'Art de la corderie perfectionné, 1747

- Traité de la fabrique des manoeuvres pour les vaisseaux (in French). Paris: Imprimerie Royale. 1747.

- Traité des arbres et arbustes qui se cultivent en France en pleine terre, 1755; 2nd edition 1785

- Traite des Arbres et Arbustes que l'on Cultive en France, 1755–67.

- Éléments de l'architecture navale, ou Traité pratique de la construction des vaisseaux, 1752 and 1758

- La Physique des arbres, 1758

- Traité des semis et plantations des arbres et de leur culture, 1760

- Éléments d'agriculture, 1762; Translated as A practical treatise on husbandry 1759. Also as The Elements of Agriculture, translated and revised by Philip Miller, 1764[8]

- Eléments d'agriculture (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Hippolyte Louis Guérin & Louis François Delatour. 1762.

- Eléments d'agriculture (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: Hippolyte Louis Guérin & Louis François Delatour. 1762.

- Histoire d'un insecte qui devore les grains de l'Angoumois, with Mathieu Tillet, published by H. L. Guérin & L. F. Delatour, Paris, 1762

- Du transport, de la conservation et de la force des bois (in French). Paris: Louis François Delatour. 1767.

- Traité de l'exploitation des bois, 1764

- Traité de la garance, et de sa culture, 1765

- Traité du transport des bois et de leur conservation, 1767

- Traité des arbres fruitiers. 1768[9][10]

- Traité géneral des pêches, 1769

References

[edit]- ^ a b "(100231) Monceau". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ International Plant Names Index. Duhamel.

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Duhamel du Monceau, Henri Louis". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 649.

- ^ Studhalter, R. A. (1955). "Tree Growth I. Some Historical Chapters". Botanical Review. 21 (1/3): 1–72. ISSN 0006-8101.

- ^ Denis Diderot. Oeuvres complètes de Diderot: revues sur les éditions originales, comprenant ce qui a été publié à diverses époques et les manuscrits inédits, conservés à la Bibliothèque de l'Ermitage, notices, notes, table analytique, Volume 11. Garnier frères, 1767. p. 366

- ^ Marquis de Condorcet. Tribute to Duhamel du Monceau, 30 April 1783

- ^ "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ Tobias Smollett: The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, Lewis M. Knapp and Paul-Gabriel Boucé, OUP Worlds Classics, 1984, p. 374, Note 4

- ^ volumes 1 and 2 volumes 2 and 3

- ^ A copy of which was one of the most expensive books ever sold at auction fetching $4.5 million. Source: The Most Expensive Books Ever Sold Archived 23 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine on blog.knowyourmoney.co.uk, February 2009

External links

[edit]- Traité Général des Pesches – A collection of plates from the book by Duhamel du Monceau and Jean-Louis de la Marre, considered one of the finest works on fishing and fisheries, from UBC Library Digital Collections

- Works by Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau at the Internet Archive