The Lost Boys

| The Lost Boys | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Joel Schumacher |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | Harvey Bernhard |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Chapman |

| Edited by | Robert Brown |

| Music by | Thomas Newman |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $8.5 million |

| Box office | $32.2 million |

The Lost Boys is a 1987 American horror comedy directed by Joel Schumacher, produced by Harvey Bernhard with a screenplay written by Jeffrey Boam, Janice Fischer and James Jeremias, from a story by Fischer and Jeremias. The film's ensemble cast includes Corey Feldman, Jami Gertz, Corey Haim, Edward Herrmann, Barnard Hughes, Jason Patric, Kiefer Sutherland, Jamison Newlander and Dianne Wiest.

The film follows two teenage brothers who move with their divorced mother to the fictional town of Santa Carla, California, only to discover that the town is a haven for vampires. The title is a reference to the Lost Boys in J. M. Barrie's stories about Peter Pan and Neverland, who, like vampires, never grow up. Most of the film was shot in Santa Cruz, California.

The Lost Boys was released by Warner Bros. Pictures on July 31, 1987, and was a critical and commercial success, grossing over $32 million against a production budget of $8.5 million. It has since then been described as a cult classic. The success of the film spawned a franchise with two sequels (Lost Boys: The Tribe and Lost Boys: The Thirst), and two comic book series.

Plot

[edit]The Emerson family—teenager Michael, his younger brother Sam, and their recently divorced mother Lucy—move to the seaside town of Santa Carla, California, to live with Lucy's eccentric father ("Grandpa"). Lucy takes a job at a video store owned by Max, who takes a romantic interest in her. At the local comic book store, Sam meets the Frog brothers, Edgar and Alan, self-proclaimed vampire hunters. They gift a skeptical Sam a horror comic on the subject to teach him about the undead threat they claim has infested the town.

Meanwhile, Michael becomes drawn to Star, a beautiful girl he meets on the boardwalk. He notices Star spending time with David, the charismatic leader of a local gang that includes Paul, Dwayne, and Marko. Sensing Michael's interest in Star, David challenges him to keep up with them on their motorcycles, ultimately leading him to their hideout in a former luxury hotel buried during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Once there, David seems to manipulate Michael's perception, making his food appear as maggots or worms, before offering him a bottle filled with red liquid. Although Star warns him that it contains blood, Michael drinks. David's gang then leads him to a railway bridge, where they hang suspended over a vast drop, each member eventually letting go and disappearing into the fog. Michael, unable to hold on, falls—but he suddenly awakens in his bed.

Michael begins to change: he becomes sensitive to light, finds normal food revolting, and notices his reflection fading. He develops a craving for blood and nearly attacks Sam, but Sam's dog, Nanook, intervenes and stops him. Though terrified, Sam agrees to help Michael and deduces that he is turning into a vampire. However, his transformation will only be complete if he feeds on human blood—and it may be reversible if they kill the head vampire. Sam, Edgar, and Alan suspect Max is the head vampire, but after Max is invited to dinner at Lucy's house, they notice he still has a reflection.

David and his gang attempt to push Michael into killing by revealing their true monstrous faces and demonstrating their ability to fly as they murder a group of partygoers. However, Michael resists the temptation to feed. Later, Star confides in Michael that she and Laddie, a young member of the gang, are also only partly transformed, as they, too, have refused to kill. She admits that David wanted her to kill Michael to complete her transformation. Determined to save her, Michael leads Sam and the Frog brothers to the gang's lair during the day while the vampires are sleeping. They stake and kill Marko, whose pained screams awaken the others. The boys narrowly escape with Star and Laddie as David vows to hunt them down that night.

Michael, Sam, and the Frog brothers prepare for the gang's impending assault, arming themselves with holy water, a longbow, and stakes. As night falls, David's gang breaks into the Emerson home. In the ensuing fight, Sam, Nanook, and the Frog brothers manage to kill Paul and Dwayne, while Michael takes on David. Michael resists David's temptation to accept his transformation, ultimately impaling him on Grandpa's collection of antlers. Despite David's death, Michael's transformation remains incomplete, leading the group to suspect that David was not the head vampire.

Lucy and Max return home from their date. Spotting David's lifeless body, Max confesses he is the head vampire. He reveals he passed the boys' earlier vampire tests because he had been invited into their home, making him immune to those vulnerabilities. Max explains that he sought a disciplined family and ordered David to turn Michael and Sam to compel Lucy into joining as a willing mother to his lost boys. To save Michael, Lucy reluctantly agrees to Max's offer. However, before Max can act, Grandpa crashes his truck through the wall, impaling Max with a large wooden fence post and causing him to explode. With Max's death, Michael, Star, and Laddie revert to normal. Grandpa then quips, "The one thing about living in Santa Carla I never could stomach: all the damn vampires."

Cast

[edit]- Jason Patric as Michael Emerson

- Corey Haim as Sam Emerson

- Dianne Wiest as Lucy Emerson

- Barnard Hughes as Grandpa

- Edward Herrmann as Max

- Kiefer Sutherland as David

- Jami Gertz as Star

- Corey Feldman as Edgar Frog

- Jamison Newlander as Alan Frog

- Brooke McCarter as Paul

- Billy Wirth as Dwayne

- Alexander Winter as Marko

- Chance Michael Corbitt as Laddie

- Alexander Bacan Chapman as Greg

- Nori Morgan as Shelly

- Kelly Jo Minter as Maria

- Tim Cappello as beach concert star

Production

[edit]Background

[edit]A March 5, 1985 Variety news item announced that the independent production company Producers Sales Organization (PSO) bought first-time screenwriters Janice Fischer and James Jeremias' Lost Boys script for $400,000 on February 20, 1985.[1] PSO announced their acquisition of the project at the American Film Market in 1985. Warner Bros. later joined the project, taking over domestic distribution and some foreign territories.[1]

The film's title is a reference to the characters featured in J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan stories, who—like vampires—never grow old. Jeremias said, "I had read Anne Rice's Interview with the Vampire, and in that there was a 200-year-old vampire trapped in the body of a 12-year-old girl. Since Peter Pan had been one of my all-time favourite stories, I thought, 'What if the reason Peter Pan came out at night and never grew up and could fly was because he was a vampire?'"[2] According to academic William Patrick Day, the central theme of The Lost Boys, "organized around loose allusions to Peter Pan", is the tension surrounding the Emerson family and the world of contemporary adolescence.[3] The film was originally set to be directed by Richard Donner, and Fischer and Jeremias' screenplay was modeled on Donner's recent film The Goonies (1985).[4] In this way the film was envisioned as more of a juvenile vampire adventure with 13 or 14-year-old vampires, while the Frog brothers were "chubby 8 year-old Cub Scouts" and the character of Star was a young boy.[5][4] When Donner committed to other projects, Joel Schumacher was approached to direct the film although Donner eventually received credit as an executive producer. He came up with the idea of making the film sexier and more adult, bringing on screenwriter Jeffrey Boam to retool the script and raise the ages of the characters.[2][6]

Casting

[edit]Schumacher said he had "one of the greatest [casts] in the world. They are what make the film." Most of the younger cast members were relatively unknown. Schumacher and Marion Dougherty met with many candidates.[6] Jason Patric was approached early on by Schumacher to play Michael, but Patric had no interest in doing a vampire film and turned it down "many times". Eventually he was won over by Schumacher's vision and his promise to allow the cast a lot of "creative input" in making the film. According to Kiefer Sutherland, Patric "was really instrumental" in adapting the script with Schumacher and shaping the film.[7]

Schumacher envisioned the character of Star as being a waifish blonde, similar to Meg Ryan, but he was convinced by Jason Patric to consider Jami Gertz, who had just worked with Patric in Solarbabies (1986). Schumacher was impressed, but only at Patric's insistence did he finally cast Gertz.[6] Schumacher was surprised when his first choice for the role of Lucy, Dianne Wiest, accepted the role, as she had just recently won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for Hannah and Her Sisters (1986).[6]

After seeing Kiefer Sutherland's portrayal of Tim in At Close Range, Schumacher arranged a reading with him at which they got on very well. Sutherland had just completed work on Stand by Me when he was offered the role of David. Schumacher said Sutherland "can do almost anything. He's a born character actor. You can see it in The Lost Boys. He has the least amount of dialogue in the movie, but his presence is extraordinary."[6]

Principal photography

[edit]Most of the film was shot in Santa Cruz, California, starting on June 2, 1986, and ending on June 23, 1986 after 21 days of filming. Locations include the Santa Cruz Boardwalk, the Pogonip open space preserve, and the surrounding Santa Cruz Mountains. Other locations included a cliffside on the Palos Verdes Peninsula in Los Angeles County, used for the entrance to the vampire cave, and a valley in Santa Clarita near Magic Mountain where introductory shots were filmed for the scene where Michael and the Lost Boys hang from a railway bridge.[8] Stage sets included the vampire cave, built on Stage 12 of the Warner Bros. lot, and a recreation of the interior and exterior of the Pogonip clubhouse on Stage 15, which stood in for Grandpa's house.[6]

Sutherland broke his right wrist while doing a wheelie on his motorcycle and had to wear gloves on set to conceal the cast. His motorcycle for the movie was adapted so he could operate it with his left hand only.[7]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The Lost Boys opened at number two during its opening weekend, with a domestic gross of over $5.2 million. It went on to gross a domestic total of over $32.2 million against an $8.5 million budget.[9][10]

Critical response

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 77% based on 77 reviews, with an average rating of 6.4/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Flawed but eminently watchable, Joel Schumacher's teen vampire thriller blends horror, humor, and plenty of visual style with standout performances from a cast full of young 1980s stars."[11] On Metacritic, it has a weighted average score of 63 out of 100 based on 16 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[12] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[13]

Roger Ebert gave the film two-and-a-half out of four stars, praising the cinematography and "a cast that's good right down the line", but ultimately describing Lost Boys as a triumph of style over substance and "an ambitious entertainment that starts out well but ends up selling its soul."[14] Caryn James of The New York Times called Dianne Wiest's character a "dopey mom" and Barnard Hughes's character "a caricature of a feisty old Grandpa." She found the film more of a comedy than a horror and the finale "funny".[15] Elaine Showalter commented that "the film brilliantly portrays vampirism as a metaphor for the kind of mythic male bonding that resists growing up, commitment, especially marriage."[16] Variety panned the film, calling it "a horrifically dreadful vampire teensploitation entry that daringly advances the theory that all those missing children pictured on garbage bags and milk cartons are actually the victims of bloodsucking bikers."[17]

The film won a Saturn Award for Best Horror Film in 1987.[18]

Cultural influence

[edit]The Lost Boys has been credited with helping shift depictions of vampires in popular culture and bringing a more youthful, sexier appeal to the vampire genre.[19][20][21] This inspired subsequent films like Buffy the Vampire Slayer.[22] The scene in which David transforms noodles into worms was directly referenced in the 2014 vampire mockumentary film What We Do in the Shadows.[23] The film inspired the song of the same name by the Finnish gothic rock band the 69 Eyes.[24] Gunship's 2018 "Dark All Day" music video and lyrics reference the themes and practical effects, on top of collaborating with Tim Cappello.[25]

The music video for "Into the Summer", a song released by American rock band Incubus on August 23, 2019, pays homage to the film.[26]

Event organizers Monopoly Events created "the biggest Lost Boys reunion ever" in 2019 at their annual horror fan convention, For the Love of Horror, which included Kiefer Sutherland, Jason Patric, Alex Winter, Jamison Newlander, and Billy Wirth along with musicians from the film, G Tom Mac, and Tim Cappello, who were reunited for the first time in over 30 years. G Tom Mac and Tim Cappello performed separate live music sets on the event stage to a vast crowd of fans on both days of the event, while Cappello performed a third time at the event after-party. All of the celebrities posed together for photographs in a purpose-built "cave" set modeled on the vampire cave seen in The Lost Boys original movie which was complete with a poster of Jim Morrison, a bottle of fake blood and David the vampire's wheelchair.[27] The group reunited once again at the 2023 event and this time Jason Patric gave a live commentary during a closed screening of the film in the venue.

The Frog brothers make a (non-canonical) cameo in Jenny Colgan's 2001 novel Looking for Andrew McCarthy, in which they are now police officers and make brief, ominous reference to their past work with "the supernatural".[28]

Home media

[edit]The film was released on DVD on January 28, 1998.[29] On August 10, 2004, the film received a special edition two-disc release, which contained an audio commentary from Schumacher, deleted scenes, and making-of featurettes.[30] The film was issued on Blu-ray on July 29, 2008.[31] For the film's 35th anniversary on September 20, 2022, it was released as a 4K Blu-ray SteelBook, in tandem with Poltergeist (1982).[32] The release includes special features ported from the 2008 edition.

Adaptations

[edit]Novelization

[edit]Due to his past fantasy novels and horror short stories, Craig Shaw Gardner was given a copy of the script and asked to write a novelization to accompany the film's release. At the time, Gardner was, like the Frog brothers, managing a comic book store as well as writing.[33]

The novelization was released in paperback by Berkley Publishing[34] and is 220 pages long. It includes several scenes later dropped from the film, such as Michael working as a trash collector for money to buy his leather jacket. It expands the roles of the opposing gang, the Surf Nazis, who were seen as nameless victims of the vampires in the film. It also includes several tidbits of vampire lore, such as not being able to cross running water and salt sticking to their forms.

Comic books

[edit]David makes a reappearance in the 2008 comic book series Lost Boys: Reign of Frogs, which serves as a sequel to the first film and a prequel to Lost Boys: The Tribe.

In October 2016, Vertigo released a comic book miniseries, The Lost Boys, where Michael, Sam, and the Frog brothers must protect Star from her sisters, the Blood Belles.[35]

Stage musical

[edit]In December 2023, a musical adaptation was reported to be in development, directed by Michael Arden with music by the Rescues.[36]

Sequels

[edit]Kiefer Sutherland's character, David, was impaled on antlers but does not explode or dissolve as do the other vampires. He was intended to have survived, which would be picked up in a sequel, The Lost Girls.[37] Scripts for this and other sequels circulated over the years; Joel Schumacher made several attempts at a sequel during the 1990s, but nothing came to fruition.[38][4]

A direct-to-DVD sequel, Lost Boys: The Tribe, was released in 2008. Corey Feldman returned as Edgar Frog, with a cameo by Corey Haim as Sam Emerson. Kiefer Sutherland's half-brother Angus Sutherland played the lead vampire, Shane Powers.[39]

A third film, Lost Boys: The Thirst, was released on DVD on October 12, 2010. Feldman served as an executive producer in addition to playing Edgar Frog, and Newlander returned as Alan Frog.[40] Haim, who was not slated to be part of the cast, died in March 2010. A fourth film was discussed as well as a Frog brothers television series,[41] but with the dissolution of Warner Premiere, the projects never materialized.[41]

In September 2021, a new film was announced, to be directed by Jonathan Entwistle, from a script by Randy McKinnon, starring Noah Jupe and Jaeden Martell.[42]

Music

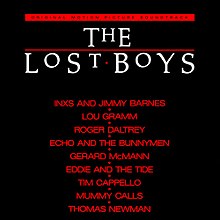

[edit]| The Lost Boys: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Soundtrack album by various artists | ||||

| Released | July 31, 1987 | |||

| Genre | Soundtrack | |||

| Length | 43:45 | |||

| Label | Atlantic[43] | |||

| Producer | Various | |||

| The Lost Boys soundtrack chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Lost boys soundtrack | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| PopMatters | Favorable[43] |

Thomas Newman wrote the original score as an eerie blend of orchestra and organ arrangements.

The music soundtrack contains a number of notable songs and several covers, including "Good Times", a duet between INXS and former Cold Chisel lead singer Jimmy Barnes which reached No. 2 on the Australian charts.[46] This cover version of a 1960s Australian song by the Easybeats was originally recorded to promote the Australian Made tour of Australia in early 1987, headlined by INXS and Barnes.

Tim Cappello's cover of the Call's "I Still Believe" was featured in the film as well as on the soundtrack. Cappello makes a cameo appearance in the film playing the song at the Santa Cruz boardwalk, with his saxophone and bodybuilder muscles on display. Cappello frequently appears at fan conventions to perform the song.

The soundtrack features a cover version of the Doors' song "People Are Strange" by Echo & the Bunnymen. The song as featured in the film is an alternate, shortened version with a slightly different music arrangement.

Lou Gramm, lead singer of Foreigner, recorded "Lost in the Shadows" for the soundtrack, along with a video which featured clips from the film.[47]

The theme song, "Cry Little Sister", was originally recorded by Gerard McMahon (under his pseudonym Gerard McMann) for the soundtrack, and later re-released on his album G Tom Mac in 2000. In the film's sequel Lost Boys: The Tribe, "Cry Little Sister" was covered by a Seattle-based rock band, Aiden[48] and appeared again in the closing credits of Lost Boys: The Thirst.

Soundtrack

[edit]- "Good Times" by Jimmy Barnes and INXS – 3:49 (The Easybeats)

- "Lost in the Shadows (The Lost Boys)" by Lou Gramm – 6:17

- "Don't Let the Sun Go Down on Me" by Roger Daltrey – 6:09 (Elton John/Bernie Taupin)

- "Laying Down the Law" by Jimmy Barnes and INXS – 4:24

- "People Are Strange" by Echo & the Bunnymen – 3:36 (The Doors)

- "Cry Little Sister (Theme from The Lost Boys)" by Gerard McMann – 4:46

- "Power Play" by Eddie & the Tide – 3:57

- "I Still Believe" by Tim Cappello – 3:42 (The Call)

- "Beauty Has Her Way" by Mummy Calls – 3:56

- "To the Shock of Miss Louise" by Thomas Newman – 1:21

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1987–1988) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (ARIA)[49] | 44 |

| Canada Top Albums/CDs (RPM)[50] | 41 |

| US Billboard 200[51] | 15 |

| Chart (1995) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Scottish Albums (OCC)[52] | 84 |

| Chart (2020) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Album Downloads (OCC)[53] | 49 |

| UK Compilation Albums (OCC)[54] | 13 |

| UK Soundtrack Albums (OCC)[55] | 2 |

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[56] | 2× Platinum | 140,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Lost Boys (1987)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films.

- ^ a b Godfrey, Alex (October 28, 2022). "The Lost Boys: Joel Schumacher On Making The Coolest Vampire Movie Of All Time". Empire. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Day, William Patrick (2002). Vampire Legends in Contemporary American Culture: What Becomes a Legend Most. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-8131-9250-5.

- ^ a b c Lyttelton, Oliver (August 1, 2012). "5 Things You Might Not Know About 'The Lost Boys' on Its 25th Anniversary". IndieWire. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- ^ The Lost Boys dvd promo. 2004. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c d e f The Lost Boys: A Retrospective (DVD). Warner Bros. Home Video. 2004.

- ^ a b The Lost Boys Panel - Jason Patric and Kiefer Sutherland. Renegade Geek. May 27, 2019. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "The Lost Boys (1987) Movie Filming Locations". The 80s Movies Rewind. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ "The Lost Boys (1987)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "The Lost Boys (1987)". The Numbers. Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- ^ "The Lost Boys (1987)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ^ "The Lost Boys". Metacritic. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "CinemaScore". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 31, 1987). "The Lost Boys". Chicago Sun-Times – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ James, Caryn (July 31, 1987). "Film: 'The Lost Boys'". The New York Times.

- ^ Showalter, Elaine (1990). Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the Fin de Siècle. New York: Viking. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-670-82503-5.

- ^ "The Lost Boys". Variety. 1987.

- ^ "1987 15th Saturn Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2006. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ Jøn, Allan (January 2001). "From Nosteratu to Von Carstein: shifts in the portrayal of vampires". Australian Folklore: A Yearly Journal of Folklore Studies (16). University of New England: 97–106. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ^ "How The Lost Boys made vampires sexy". GamesRadar+. June 29, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ Winning, Joshua (March 11, 2010). "The Story Behind The Lost Boys". GamesRadar+. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Diaz, Eric (August 10, 2012). "Celebrating 25 Years of "The Lost Boys"". Geekscape. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ Hunter, Rob (July 20, 2015). "32 Things We Learned From the What We Do In the Shadows Commentary". Film School Rejects. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ Hartmann, Graham (October 26, 2012). "'The Lost Boys' – Horror Movies That Inspired Songs". Loudwire. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Marotta, Michael O'Connor (July 13, 2018). "Gunship join forces with 'Lost Boys' sax man Tim Cappello and Indiana". Vanyaland. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ "Incubus release video for new single, Into The Summer". Kerrang!. August 23, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

Incubus pay homage to The Lost Boys in the video for the first single from their upcoming new album.

- ^ Torok, Frankie (November 2, 2019). "'The Lost Boys' Reunite at For the Love of Horror 2019 [Panel Highlights]". Horror Geek Life. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ Colgan, Jenny (2001). Looking for Andrew McCarthy. HarperCollins. pp. 256–260. ISBN 0007105533.

- ^ The Lost Boys. ASIN 6304779356.

- ^ ""The Lost Boys Two-Disc Special Edition" DVD From Warner Home Video" (Press release). Warner Bros. May 3, 2004. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ "The Lost Boys Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ "The Lost Boys 4K Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ Reed, Patrick A. (July 3, 2014). "Novelist Craig Shaw Gardner On Adapting Batman '89 For Prose [Interview]". ComicsAlliance.

- ^ "The Lost Boys by Craig Shaw Gardner". Fantastic Fiction.

- ^ Prudom, Laura (July 15, 2016). "'The Lost Boys' Sequel Comic in the Works from Vertigo (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety.

- ^ Lang, Brent (December 13, 2023). "The Lost Boys Being Made Into Musical With 'Parade' Director Michael Arden, The Rescues". Variety.

- ^ Topel, Fred (February 4, 2007). "Joel Schumacher Lost in "Lost Boys" Sequel". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ Stephenson, Hunter (August 13, 2008). "Kiefer Sutherland Talks Lost Boys Prequel, Tells The Tribe to FO". /Film. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ Caffeinated Clint (August 29, 2007). "Wanna know who The Lost Boys are?". Moviehole. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ Wigler, Josh (March 18, 2009). "'Lost Boys' Threequel On The Way, Corey Feldman To Return". MTV Movies Blog. Archived from the original on March 22, 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- ^ a b Orange, B. Alan (November 23, 2012). "The Lost Boys 4 Is Dead and the Frog Brothers TV Series Is Homeless". MovieWeb. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ Kit, Borys (September 17, 2021). "New 'Lost Boys' Movie in the Works with Noah Jupe, Jaeden Martell to Star (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ a b Harris, Mark H. (August 18, 2005). "The Cut-Out Bin #2: Soundtrack, Lost Boys (1987)". PopMatters. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Barnes and INXS".

- ^ "The Lost Boys – Original Soundtrack". AllMusic.

- ^ Elliott, Bart (May 14, 2015). "Jon Farris: INXS & Jimmy Barnes – "Good Times"". Drummer Cafe. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Cabbage, Jack (October 27, 2008). "Lou Gramm: Lost in the Shadows (1987)".

- ^ Cabbage, Jack (October 26, 2008). "Gerard McMann: Cry Little Sister (1987)".

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Soundtrack – The Lost Boys". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 0880". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Soundtrack Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Official Album Downloads Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Official Compilations Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Official Soundtrack Albums Chart Top 50". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2002 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

External links

[edit]- 1987 films

- The Lost Boys (franchise)

- 1987 black comedy films

- 1987 comedy horror films

- 1980s American films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s monster movies

- 1980s supernatural horror films

- 1980s teen comedy films

- 1980s teen horror films

- American black comedy films

- American comedy horror films

- American supernatural comedy films

- American supernatural horror films

- American teen comedy films

- American teen horror films

- American vampire films

- English-language comedy horror films

- Films about brothers

- Films about single parent families

- Films directed by Joel Schumacher

- Films scored by Thomas Newman

- Films set in Santa Cruz County, California

- Films shot in California

- Films with screenplays by Jeffrey Boam

- Saturn Award–winning films

- Teensploitation

- Vampire comedy films

- Warner Bros. films