Louis Vauxcelles

Louis Vauxcelles (French pronunciation: [lwi vosɛl]; born Louis Meyer; 1 January 1870 – 21 July 1943[1]) was a French art critic.[2] He is credited with coining the terms Fauvism (1905) and Cubism (1908). He used several pseudonyms in various publications: Pinturrichio, Vasari, Coriolès, and Critias.[3]

Fauvism

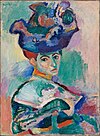

[edit]Vauxcelles was born in Paris. He coined the phrase 'les fauves' (translated as 'wild beasts') in a 1905 review of the Salon d'Automne exhibition to describe in a mocking, critical manner a circle of painters associated with Henri Matisse. As their paintings were exposed in the same room as a Donatello sculpture of which he approved, he stated his criticism and disapproval of their works by describing the sculpture as "a Donatello amongst the wild beasts."[4]

Henri Matisse's Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra) appeared at the 1907 Indépendants, entitled Tableau no. III. Vauxcelles writes on the topic of Nu bleu:

I admit to not understanding. An ugly nude woman is stretched out upon grass of an opaque blue under the palm trees... This is an artistic effect tending toward the abstract that escapes me completely. (Vauxcelles, Gil Blas, 20 March 1907)[5]

Vauxcelles described the group of 'Fauves':

A movement I consider dangerous (despite the great sympathy I have for its perpetrators) is taking shape among a small clan of youngsters. A chapel has been established, two haughty priests officiating. MM Derain and Matisse; a few dozen innocent catechumens have received their baptism. Their dogma amounts to a wavering schematicism that proscribes modeling and volumes in the name of I-don't-know-what pictorial abstraction. This new religion hardly appeals to me. I don't believe in this Renaissance... M. Matisse, fauve-in-chief; M. Derain, fauve deputy; MM. Othon Friesz and Dufy, fauves in attendance... and M. Delaunay (a fourteen-year-old-pupil of M. Metzinger...), infantile fauvelet. (Vauxcelles, Gil Blas, 20 March 1907).[5]

Cubism

[edit]In 1906 Jean Metzinger formed a close friendship with Robert Delaunay, with whom he would share an exhibition at Berthe Weill's gallery early in 1907. The two of them were singled out by Vauxcelles in 1907 as Divisionists who used large, mosaic-like 'cubes' to construct small but highly symbolic compositions.[6][7][8]

In 1908, Vauxcelles again, in his review of Georges Braque's exhibition at Kahnweiler's gallery called Braque a daring man who despises form, "reducing everything, places and a figures and houses, to geometric schemas, to cubes".[9][10]

Vauxcelles recounts how Matisse told him at the time, "Braque has just sent in [to the 1908 Salon d'Automne] a painting made of little cubes".[10] The critic Charles Morice relayed Matisse's words and spoke of Braque's little cubes. The motif of the viaduct at l'Estaque had inspired Braque to produce three paintings marked by the simplification of form and deconstruction of perspective.[11]

On 25 March 1909, Vauxcelles qualifies the works of Braque exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants as "bizarreries cubiques" (cubic oddities).[12]

Vauxcelles, this time in his review of the 26th Salon des Indépendants (1910), made a passing and imprecise reference to Henri Le Fauconnier, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger, as "ignorant geometers, reducing the human body, the site, to pallid cubes."[13][14]

"In neither case" notes Daniel Robbins, "did the use of the word "cube" lead to the immediate identification of the artists with a new pictorial attitude, with a movement. The word was no more than an isolated descriptive epithet that, in both cases, was prompted by a visible passion for structure so assertive that the critics were wrenched, momentarily, from their habitual concentration on motifs and subjects, in which context their comments on drawing, color, tonality, and, only occasionally, conception, resided." (Robbins, 1985)[14]

The term "Cubism" emerged for the first time at the inauguration of the 1911 Salon des Indépendants; imposed by journalists who wished to create sensational news.[15] The term was used derogatorily to describe the diverse geometric concerns reflected in the paintings of five artists in continual communication with one another: Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, Le Fauconnier and Léger (but not Picasso or Braque, both absent from this massive exhibition).[7]

Vauxcelles acknowledged the importance of Cézanne to the Cubists in his article titled From Cézanne to Cubism (published in Eclair, 1920). For Vauxcelles the influence had a two-fold character, both 'architectural' and 'intellectual'. He stressed the statement made by Émile Bernard that Cézanne's optics were "not in the eye, but in his brain".[16]

In 1911 he coined the less well-known term Tubism in describing the style of Fernand Léger.[17]

Legacy

[edit]In 1906 Louis Vauxcelles was named Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, and in 1925 he was promoted to Officer of the Legion of Honour.[18]

Towards the end of his life, in 1932, Vauxcelles published a monographic essay about Marek Szwarc, dedicated to the Jewish character of Szwarc's oeuvre.

"His art, which plunges its roots into the past of the ghettos and in which the moving accent like the ancient songs in the synagogue of Wilna, is a return to popular imagery. And, in as much as this may seem paradoxical, these stern manners, this severe style, of a "common" naïveté, are profoundly in accord with what art of the most modernist sort supplies in our regard; by virtue of its poetic concepts, by its firm and generous execution, by the sense of its cadenced dispositions, by the sharp graphics written in view of the material and which commands this very material, it is apparent that Marek Szwarc is in harmony with the most audacious innovators of our times, who seek him out and see him as a maître."[19]

He died in Neuilly sur Seine outside Paris, aged 73 and was buried in the Old Cemetery of Neuilly sur Seine.

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Vauxcelles, Louis (1870–1943). Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Stanley Meisler, Shocking Paris: Soutine, Chagall and the Outsiders of Montparnasse, p. 54

- ^ Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Mathilde Arnoux, Friederike Kitschen, Perspectives croisées: la critique d'art franco-allemande 1870–1945, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme, 2009, p. 578

- ^ Vauxcelles, Louis (17 October 1905). "Le Salon d'Automne" [The Fall Salon]. Gil Blas (in French) (9500). Paris: Augustin-Alexandre Dumont: Supplement, 6. ISSN 1149-9397. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

La candeur de ces bustes surprend, au milieu de l'orgie des tons purs : Donatello chez les fauves

- ^ a b Russell T. Clement, Les Fauves: A sourcebook, Greenwood Press, 1994, ISBN 0-313-28333-8

- ^ Robert L. Herbert, 1968, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

- ^ a b Daniel Robbins, 1964, Albert Gleizes 1881 – 1953, A Retrospective Exhibition, Published by The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, in collaboration with Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund

- ^ Art of the 20th Century

- ^ Louis Vauxcelles, Exposition Braques, Gil Blas, 14 November 1908

- ^ a b Alex Danchev, Georges Braques: A Life, Arcade Publishing, 15 nov. 2005

- ^ Futurism in Paris – The Avant-garde Explosion, Pompidou Center, Paris 2008

- ^ Louis Vauxcelles, Le Salon des Indépendants, Gil Blas, 25 March 1909, Gallica (BnF)

- ^ Louis Vauxcelles, A travers les salons: promenades aux Indépendants, Gil Blas, 18 March 1910

- ^ a b Daniel Robbins, Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art (J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press) p. 13

- ^ Albert Gleizes Souvenirs, le cubisme 1908–14, Cahiers Albert Gleizes 1 (Lyon, 1957), p. 14

- ^ Christopher Green, Cubism and its Enemies, Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–28, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1987, p. 192

- ^ Néret, 1993, p. 42

- ^ Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, Base Léonore, Archives Nationales, Culture.gouv.fr

- ^ "Marek Szwarc". marekszwarc.com. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- Néret, Gilles (1993). F. Léger. New York: BDD Illustrated Books. ISBN 0-7924-5848-6