Lotus Elite

The Lotus Elite name has been used for two production vehicles and one concept vehicle developed and manufactured by British automobile manufacturer Lotus Cars. The first generation Elite Type 14 was produced from 1957 until 1963 and the second generation model (Type 75 and later Type 83) from 1974 until 1982. The Elite name was also applied to a concept vehicle unveiled in 2010.

Type 14 (1957–1963)

[edit]| Lotus Elite Type 14 | |

|---|---|

Lotus Elite SE | |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | |

| Production | 1957–1963 |

| Designer |

|

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Sports car (S) |

| Body style | 2-door coupé |

| Layout | Front-engine, rear-wheel-drive |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | 1.2 L Coventry Climax FWE I4[1] |

| Transmission | 4-speed manual |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 2,242 mm (88.3 in)[2] |

| Length | 3,759 mm (148.0 in)[2] |

| Width | 1,506 mm (59.3 in) [2] |

| Height | 1,181 mm (46.5 in)[2] |

| Kerb weight | 503.5 kg (1,110 lb) |

| Chronology | |

| Successor | Lotus Elan |

The first generation of the Elite or Lotus Type 14 was a light weight two-seater coupé produced from 1957 until 1963.

The car debuted at the 1957 London Motor Car Show, Earls Court bearing chassis number #1008.[3] The Elite had spent a year in development, aided by "carefully selected racing customers" before going on sale.[4]

The Elite's most distinctive feature was its highly innovative fibreglass monocoque construction, in which a stressed-skin Glass reinforced plastic unibody replaced the previously separate chassis and body components. Unlike the contemporary Chevrolet Corvette, which used fibreglass for only exterior bodywork, the Elite used glass-reinforced plastic for the entire load-bearing structure of the car. A steel subframe for supporting the engine and front suspension was bonded into the front of the monocoque, as was a square-section windscreen-hoop that provided mounting points for door hinges, a jacking point for lifting the car and roll-over protection components.[5] The first 250 body units were made by Maximar Mouldings at Pulborough, Sussex.[6] The body construction caused numerous early problems, until manufacture was handed over to Bristol Aeroplane Company.[4]

The resultant body was lighter, stiffer, and provided better driver protection in the event of a crash. Still, a full understanding of the engineering qualities of fibreglass-reinforced plastic was several years off and the suspension attachment points were regularly observed to pull out of the fibreglass structure. The weight savings allowed the Elite to achieve sports car like performance from a 75 hp (56 kW), 1,216 cc (1.2 L) Coventry Climax FWE all-aluminium Inline-four engine while returning a fuel consumption of 35 mpg‑imp (8.1 L/100 km; 29 mpg‑US).[1] All production Elites were powered by the FWE engine, except for one that acted as testbed for the newly developed Lotus-Ford Twin Cam engine. The FWE engine was derived from a lightweight (FW = Feather Weight) high-capacity water pump engine used for firefighting.[7]

The car had independent suspension all round with transverse wishbones at the front and Chapman struts at the rear. The rear struts were so long, that they poked up in the back and the tops could be seen through the rear window.[1] The Series 2 cars, with Bristol-built bodies, had triangulated trailing radius arms for improved toe-in control. Girling disc brakes, usually without servo assistance, of 9.5 in (241 mm) diameter were used, inboard at the rear. When leaving the factory the Elite was originally fitted with Pirelli Cinturato 155HR15 tyres.

Advanced aerodynamics also contributed to the car's low drag coefficient of Cd=0.29[1] considering the engineers did not enjoy the benefits of computer-aided design or wind tunnel testing. The original Elite drawings were by Peter Kirwan-Taylor. Frank Costin (brother of Mike, one of the co founders of Cosworth), at that time Chief Aerodynamic Engineer for the de Havilland Aircraft Company, contributed to the final design.

The SE was introduced in 1960 as a higher-performance variant, featuring twin SU carburettors and fabricated exhaust manifold resulting in engine power output increasing to 85 hp (63 kW), ZF gearboxes in place of the standard "cheap and nasty" MG ones,[4] Lucas PL700 headlamps,[8] and a silver coloured roof. The Super 95 model[4] had a more powerful engine with raised compression ratio and a stronger camshaft with five bearings. A limited number of Super 100 and Super 105 cars were made with Weber carburettors, for racing use.

Among the Elite's few faults was a resonant vibration at 4,000 rpm (where few drivers remained, on either street or track)[9] and poor quality control, handicapped by an overly low price (resulting in Lotus losing money on every car produced) and, "perhaps the greatest mistake of all", offering it as a kit (with a substantial reduction in price and Purchase Tax), exactly the opposite of the ideal for a quality manufacturer.[4] Many drive-train parts were highly stressed and required re-greasing at frequent intervals.

When production ended in 1963, 1,030 cars had been built.[10] Other sources indicate that 1,047 were produced.[11]

A road car tested by The Motor magazine in 1960 resulted in a top speed of 111.8 mph (179.9 km/h) and a 0–60 mph (97 km/h) acceleration time of 11.4 seconds. A fuel consumption of 40.5 mpg‑imp (6.97 L/100 km; 33.7 mpg‑US) was recorded. The test car cost £1,966 including taxes.[2]

Legacy

[edit]The ownership and history of the more than 1,000 Elites is maintained by the Lotus Elite World Register.[12] There are several active clubs devoted to the Lotus Elite.[13]

Motor sport

[edit]

Like its siblings, the Elite was campaigned in numerous formulae, with particular success at Le Mans and the Nürburgring. The Elite won in its class six times at the 24 hour of Le Mans race as well as two Index of Thermal Efficiency wins. Les Leston, driving DAD10, and Graham Warner, driving LOV1, were noted UK Elite racers. In 1961, David Hobbs fitted a Hobbs Mecha-Matic 4-speed automatic transmission to an Elite,[14] and became almost unbeatable in two years' racing – he won 15 times from 18 starts. New South Wales driver Leo Geoghegan won the 1960 Australian GT Championship at the wheel of a Lotus Elite.[15] After winning Index of Thermal Efficiency prize, Lotus decided to go for an outright win at Le Mans in 1960. They built a one-off Elite, called the LX, with a 1,964 cc (2.0 L) FPF engine, larger wheels, and other modifications. In testing, it proved capable of a top speed of 174 mph (280 km/h). Unfortunately, the lead driver withdrew the night before the race, so the car did not have a chance to prove itself in competition.[16]

Types 75 and 83 (1974–1982)

[edit]| Lotus Elite Types 75 and 83 | |

|---|---|

Lotus Elite Type 75 | |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Lotus Cars |

| Production | 1974–1982 2,535 produced |

| Assembly | England: Hethel, Norfolk |

| Designer | Oliver Winterbottom |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Sports car (S) |

| Body style | 2-door 2+2 shooting brake |

| Layout | Front-engine, rear-wheel-drive |

| Related | Lotus Eclat |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | |

| Transmission |

|

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 2,490 mm (98.0 in) |

| Length | 4,470 mm (176.0 in) |

| Width | 1,820 mm (71.7 in) |

| Height | 1,210 mm (47.6 in) |

| Kerb weight | 1,112 to 1,168 kg (2,452 to 2,575 lb)[17] |

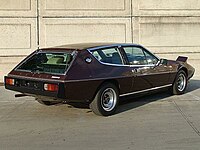

From 1974 to 1982, Lotus produced the considerably larger four-seat Type 75 and later Type 83 Elite. With this design Lotus sought to position itself upmarket and move away from its kit-car past.[18] The Elite was announced in May 1974.[19] It replaced the ageing Lotus Elan Plus 2.

The Elite has a shooting brake body style, with a glass rear hatch opening into the luggage compartment. The Elite's fibreglass bodyshell was mounted on a steel backbone chassis evolved from the Elan and Europa. It had 4-wheel independent suspension using coil springs. The Elite was the first Lotus automobile to use the aluminium-block 4-valve, DOHC, four-cylinder Type 907 engine that displaced 1,973 cc (120.4 cu in) and was rated at 155 hp (116 kW). With this engine the car does 0–60 mph (0–97 km/h) in 8.1 seconds and reaches a top speed of 125 mph (201 km/h). (The 907 engine had previously been used in Jensen-Healeys.) The 907 engine ultimately became the foundation for the 2.0 L and 2.2 L Esprit power-plants, the naturally aspirated 912 and the turbocharged 910. The Elite was fitted with a 4 or 5-speed manual transmission depending on the customer specifications. Beginning in January 1976, an automatic transmission was optional.

The Elite had a claimed drag co-efficient of 0.30 and at the time of launch, it was the world's most expensive four-cylinder car. The Elite's striking shape was designed by Oliver Winterbottom. He is quoted as saying that the basic chassis and suspension layout were designed by Colin Chapman, making the Elite and its sister design the Eclat the last Lotus road cars to have significant design input from Chapman himself.[20]

The Elite was available in four main variations, set apart by equipment levels: 501, 502, 503, and later on 504.

- 501 - "Base" version.

- 502 - Added air-conditioning to the base model.

- 503 - Added air-conditioning and power-steering.

- 504 - Added air-conditioning, power-steering and automatic transmission.

The Elite was the basis for the Eclat, and the later Excel 2+2 coupés.

Although larger and more luxurious than previous Lotus road cars, the Elite and Éclat are relatively light, with kerb weights not much over 2,300 lb (1,043 kg).

In 1980 the Type 75 was replaced by the Type 83, also called the Elite Mark 2.[21] This version received a larger 2,174 cc (132.7 cu in) Lotus 912 engine.[21] The chassis was now galvanised steel and the five speed BMC gearbox was replaced by a Getrag Type 265 unit.[21] The vacuum-operated headlights of the earlier model were replaced with electrically operated units and the Elite was now fitted with a front spoiler, a new rear bumper and brake lights from the Rover SD1.[21]

-

1978 Lotus Elite S2 (Type 75)

-

1981 Lotus Elite S2.2 (Type 83)

Elite concept

[edit]On 20 September 2010, Lotus unveiled photos of an Elite concept that was exhibited at the 2010 Paris Motor Show. The car was expected to go into production in 2014.[22]

The car was to feature a 5.0-litre V8 engine sourced from Lexus, rated at 592 hp (441 kW). The car would have a front-mid engine layout to distribute weight evenly at all four wheels. An optional hybrid kinetic-energy recovery system would augment the V8 by feeding electricity generated by braking to motors in the transmission. The 0–100 km/h (62 mph) time was reported to be as low as 3.5 seconds, with a top speed of 315 km/h (196 mph).[23]

The car had a 2+2 body style and was to be marketed as a grand tourer.

The Elite project was cancelled in July 2012 after a take over of Lotus' then parent company Proton by DRB-Hicom which initiated a new cost effective business plan.[24]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Willson, Quentin (1995). The Ultimate Classic Car Book. DK Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-7894-0159-2.

- ^ a b c d e "The Lotus Elite". The Motor. 11 May 1960.

- ^ "Elite #1008 – The 1958 Earls Court Show Car". Club Elite Newsletter. No. 31. December 2011. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017 – via Lotus Elite World Register.

- ^ a b c d e Setright, L. J. K. (1974), "Lotus: The Golden Mean", in Northey, Tom (ed.), World of Automobiles, vol. 11, London: Orbis, p. 1227

- ^ Setright, p.1226.

- ^ Crombac, Gérard (1986), Colin Chapman – The Man and His Cars, Patrick Stephens Ltd., p. 93, ISBN 978-0850597332

- ^ Taverner, Michael. "Coventry Climax Industrial Water Pump Engine" (PDF). Club Elite North America Newsletter. Vol. 2, no. 1. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2014 – via Lotus Elite World Register.

- ^ Lucas PL700 headlamps Lotus Elite World Register.

- ^ It was cured by substituting a diaphragm clutch spring. Setright, p.1227.

- ^ Ortenburger, Dennis "The Original Lotus Elite, Racing Car for the Road" Newport Press, 1977 p.135.

- ^ Trummel, Reid (April 2014). "1960 Lotus Elite Series II". Sports Car Market. 26 (4): 71.

- ^ Lotus Elite World Register Lotus Elite World Register

- ^ Lotus Elite Clubs Lotus Elite World Register

- ^ Hobbs' Mecha-Matic Automatic Transmission Club Elite Newsletter, Vol 1, No. 1; Motor Sports, December 1962

- ^ Australian Titles Archived 2 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved from www.camsmanual.com.au on 16 April 2009

- ^ Lawrence, Mike (December 1998). "The Lotus that should have won Le Mans". Motor Sport magazine archive. p. 44. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Lotus Cars Workshop Manual

- ^ Robson, Graham (6 September 1993), Lotus since the 70's Vol. 1: Elite, Eclat, Excel, Elan Collector's Guide, Motor Racing Publications, ISBN 978-0947981709

- ^ "Four-seat Elite from Lotus costs £6,000". The Times (59089): 4. 15 May 1974.

- ^ Octane Magazine "Lotus Legends" (2010)

- ^ a b c d The Lotus Elite Mark 2 Type 83 Sports Car, www.sportscar2.com Retrieved 19 February 2017

- ^ Cropley, Steve (1 October 2010). "Paris Motor Show: Lotus Elite". autocar.co.uk. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ Autos. "Lotus moving beyond hardcore sportscars with new Elite – The Passing Lane". Thepassinglane.ca. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Okulski, Travis (25 July 2012). "Lotus Cancels Nearly All Of Dany Bahar's Future Lotus Cars". Retrieved 22 October 2018.

External links

[edit]- Lotus type 14 Elite research and early history of company surrounding restoration of EB-1468

- Lotus Elite at the Internet Movie Cars Database