House of Loredan

The House of Loredan (Italian: [lore'dan], Venetian: [loɾeˈdaŋ]) is a Venetian noble family of supposed ancient Roman origin, which has played a significant role in shaping the history of the Mediterranean world. A political dynasty, the family has throughout the centuries produced a number of famous personalities: doges, statesmen, magnates, financiers, diplomats, procurators, military commanders, naval captains, church dignitaries, and writers.

In the centuries following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Loredans were lords in Emilia-Romagna, from where they came to Venice in the early 11th century. Settling there, the family grew in power in the High Middle Ages, amassing great wealth on the lucrative silk and spice trade, and in the following centuries it became powerful and influential in regions across the Mediterranean, playing a significant role in shaping its history throughout the Late Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the early modern period. The family was present in virtually every home and overseas territory of the Republic of Venice, and at various points in history, its members have held titles in what are now modern countries of Italy, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, Albania, France, Greece and Cyprus, and conducted trade operations as far as Egypt, Persia, India and China. Alongside other families of Venice's urban nobility, they played a major role in fostering mercantilism and early capitalism.

Although the Loredans were proponents of Venice's traditional, maritime orientation, and viewed with distrust its expansion on the Italian mainland, they played a key role in the territorial development, and ultimately, the history of the Republic of Venice, helping to expand its Mainland Dominions and the State of the Sea. The family was significant in the War of the League of Cambrai, with Doge Leonardo Loredan leading Venice to a victory against the Papal States, which resulted in the pope having to pay the Loredan family a financial settlement of approximately 500,000 ducats, an enormous amount of money, making them one of the richest families in the world at the time. Furthermore, many of its members distinguished themselves as admirals and generals in defending Europe from the Ottoman conquests in the Ottoman-Venetian wars. Their various naval triumphs have been honoured with the MV Loredan auxiliary cruiser of the Italian Royal Navy.

The family has also played an important role in the creation of modern opera with the Accademia degli Incogniti, also called the Loredanian Academy, and has commissioned many works of art by artists of the Venetian School, including Giovanni and Gentile Bellini, Giorgione, Vittore Carpaccio, Vincenzo Catena, Sebastiano del Piombo, Titian, Paris Bordone, Jacopo and Domenico Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Palma il Giovane, Canaletto, Pietro Longhi and Francesco Guardi, among others. At the height of the Renaissance, the family's residences were being designed and constructed by renowned architects, notably Mauro Codussi, Jacopo Sansovino, and Andrea Palladio.

The wealth of the Loredan family in Venice was legendary, likely reaching its height in the 18th century, when they owned numerous palaces, as well as hundreds of estates and vast land holdings across the territories of the Republic, primarily in the Veneto, Friuli, Istria and Dalmatia. Besides the silk and spice trade, they also participated in the medieval slave trade, and were, more than once, accused of usury and sodomy, often by long-time political rivals such as the Faliero and Foscari families. In cases of corruption, assault, murder and other scandals, when members of their own family were involved, the Loredans usually pursued a policy of lenience and outright tolerance, and aimed to resolve relating accusations by means of threats or bribery.

Under a Loredan government, the first Jewish ghetto in the world was created in Venice in 1516, although some members of the family argued in the Senate for the reduction of the sum the Jews had to pay for their "conduct". In the 17th century onwards, the Loredans were noted for supporting and taking in Jews arriving in Venice, several of whom adopted the 'Loredan' name in recognition of the family's generosity.

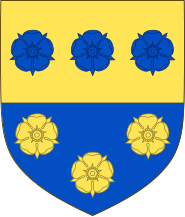

Today, the Loredan coat of arms, which features six laurel (or rose) flowers on a shield of yellow and blue, is displayed on numerous buildings and palaces across the territories previously held by the Republic of Venice; from the Veneto and Friuli, Istria and Dalmatia, and in the more distant possessions such as the Ionian Islands and Crete. In Venice, it is even carved into the Rialto Bridge and the façade of St. Mark's Basilica.

Origin and etymology

[edit]

Some historians traced the origin of the family back to the Mainardi family, in turn descended from Gaius Mucius Scaevola. They then acquired the surname of Laureati because of their ancestors' historical glory. Also, according to legend, they founded the city of Loreo in 816 AD, and moved to the Venetian Lagoon in 1015 AD. The first written references of the family, however, date from the 11th century.[1]

According to what the 16th-century Italian philosopher Jacopo Zabarella wrote in his work Trasea Peto, the Loredans were already lords of Bertinoro in Emilia-Romagna, and were of illustrious ancient lineage derived from Rome, where they earned great fame for the many victories they achieved in battles.[2] They were thus called Laurae by the Romans, then Laureati for their excellence and later Lauretani for corruption, because of which they were driven out of Bertinoro. They then went to Ferrara, and finally to Venice, where they built the Castle of Loredo. Because of their nobility, as well as for the wealth they possessed, they were ascribed by the Republic to its Great Council in 1080, with the person of Marco Loredan. Zabarella also notes the family owned the lordship of Antipario (today Antiparos, Greece) in the Aegean Sea, and more recently the county of Ormelle in the Province of Treviso.[3]

The name of the family may also have originated from the word for the flower laurel, a symbol of triumph and nobility. The coat of arms of the Loredan family features six laurel (or rose) flowers.[3]

The name may also mean "coming from Loreo", as to describe a person who is from the homonymous town.[b] Citizens of Loreo are today called "Loredani".

In addition to the Venetian branch, there was also a Sicilian branch (Loredans of Sicily).[4]

Cadet branches

[edit]Throughout history, the family was organised and divided into many branches, most of which were traditionally named after Venetian toponyms, usually parishes, as was common with Venetian nobility. Some of the branches are: Santo Stefano (extinct in 1767), San Pantaleone della Frescada, San Cancian, San Vio, Santa Maria (Formosa and Nova), San Luca, San Marcilian, Sant’Aponal etc.[5] Pietro Loredan, a member of the San Cancian branch, is also the progenitor of the branches of Santa Maria Formosa and Nova by his sons Giacomo and Polo.

Santo Stefano

The family branch of Santo Stefano (also called San Vitale) was settled in the Palazzo Loredan in Campo S. Stefano.[6] The progenitor of this branch is considered to be Gerolamo Loredan di S. Vitale, father of Doge Leonardo Loredan. Besides Leonardo, the branch also gave Doge Francesco Loredan, as well as Dogaressa Caterina Loredan and the ambassador Francesco Loredan. This branch was also significant as its members were feudal owners of the towns of Barban and Rakalj in Istria, which they acquired in an auction in 1535 for 14,700 ducats. The main (agnatic) line of the branch of Santo Stefano ended with Andrea di Girolamo Loredan, who died young in 1750, though the branch became extinct in 1767 with the death of Giovanni Loredan, brother of Doge Francesco.[7]

San Pantaleone della Frescada

The family branch of San Pantaleone della Frescada was settled around the Church of San Pantaleone Martire in the Dorsoduro district of Venice, near the Rio della Frescada canal. This branch was the one that gave Doge Pietro Loredan.[8]

San Cancian

The family branch of San Cancian was settled in the Palazzo Loredan a San Cancian in the Cannaregio district of Venice. This branch is known to have produced an illustrious dynasty of admirals and politicians including Pietro Loredan (1372–1438), Alvise Loredan (1393–1466), Giacomo Loredan (1396–1471), Giorgio Loredan (d. 1475), Antonio Loredan (1446–1514), as well as the Duke of Candia Giovanni Loredan (d. 1420).[9]

Santa Maria

The family branch of Santa Maria draws its name from the parishes of Santa Maria Formosa and Santa Maria dei Miracoli, around which it was historically settled. Its progenitor is considered to be the admiral and procurator Pietro Loredan, by his sons Giacomo and Polo. One of its most notable members is Antonio Loredan, governor of Venetian Dalmatia, Albania and Morea, known for the successful defence of Scutari in 1474 from the Ottomans.[10] He also served as the Captain General of the Sea in the Venetian navy, as did his father and grandfather.[11] Giovanni Loredan, Lord of Antiparos, is significant for building the Castle of Antiparos in 1440 and bringing inhabitants to the island at his own expense.[12] Taddea Caterina Loredan, Duchess of the Archipelago was the wife of Francesco III Crispo, known as the "Mad Duke", who murdered her in 1510.[13] Giovanni Francesco Loredan was a writer and politician who played a significant role in the creation of modern opera with his Accademia degli Incogniti.[14] Marco Loredan was a senator and politician, as well as Count of Brescia, Feltre, Rovigo, Salò and Famagusta.[15]

San Vio

The family branch of San Vio (with the Palazzo Loredan Cini) was historically settled in Campo San Vio in the Dorsoduro district of Venice. The branch still exists today.

History

[edit]13th century: The Serrata, silk, spices and slavery

[edit]

The Loredan family has been occupying hereditary seats on the Great Council since the Great Council Lockout (Serrata del Maggior Consiglio) of 1297, by which the membership in the Great Council of Venice became a hereditary title, and was limited to the families inscribed in the Golden Book of the Venetian nobility.[16] This resulted in the exclusion of minor aristocrats and plebeians from participating in the Government of the Republic.[17][d]

Like many Venetian patricians, the Loredans participated in the lucrative silk and spice trade, thus growing their wealth and influence,[18] with Venice and other maritime republics monopolising European trade with the Middle East. The family also participated in the medieval slave trade,[18] with Venice already having established slave trading operations centuries prior.[g]

Around this time, documents from the 1290s show that two Loredans, Zanetto and Zorzi, were being sued by Christian merchants from Amalfi, presumably for involvement in piracy activities, as they had seized a vessel of the coast of Malta.[19]

14th century: Conspiracies and expansion of trade

[edit]Some members of the family played a part in the bloody Tiepoline conspiracy of 1310, which involved the Querini, Badoer and other families of the old aristocracy, in an attempt to overthrow the state, primarily the doge and the Great Council. Evidence indicates the Loredans initially supported the conspiracy, having recently married into the Tiepolo family.[20] The plot failed due to treachery, bad planning, insufficient popular support and stormy weather. The rebels were stopped near Piazza San Marco by forces faithful to Doge Pietro Gradenigo and defeated. On the night before the uprising, particulars of the plot were unveiled to the doge and his advisors; the Loredans who were involved in the conspiracy passed cunningly to the other side, and to show their loyalty to the doge, they hounded the involved conspirators until they were found.[19]

The Loredans are characterised by many interesting things and stories, one of which took place in the early 14th century: In 1316, Zanotto Loredan was seriously ill, so much so that it was thought he was dead, so the people took him to the church of San Matteo in Murano for burial. After the funeral rite, they wanted to deposit the body in the tomb, when someone noticed that the color of his face had changed. They took him to the convent hospital, warmed him and he recovered. Later he continued to live normally, married and had children.[21][22]

On the influence exerted by the travels of the Marco Polo, new documents have come to light from archival research. From these it is noted that, starting as early as the 1320s, Venetian merchants flocked to Persia (where from 1324 Venice had its own consul in Tabriz), India and China, where they formed trade companies.[23] Head of one of these companies was Giovanni Loredan, whose venture along with five other nobles is a representative example of a commenda, known in Venice as colleganza, an early form of limited partnership, which implied an agreement between an investing partner and a travelling partner to conduct a commercial enterprise, usually overseas. Their journey began in 1338 when they sailed on the galleys of Romania to Tana in order to embark upon a voyage to Delhi. Following the travels of the Polos, a number of Venetians travelled across Central Asia to China. However, striking out east from Tana and then heading south around the edge of the Pamir mountains to cross the Hindu Kush mountains to India had not been done before; it was trying something new. Before this, Giovanni Loredan had just come back from a trip to China, and his wife and children therefore tried to dissuade him from the new voyage. However, Giovanni believed that there was a fortune to be made by a visit to a certain Indian prince, who had a reputation for cruelty but also generosity to foreign merchants.[24] Therefore, Giovanni, along with five other nobles who had joined in the venture, including his brother Paolo, pooled funds together in order to bring with them gifts, mechanical wonders such as a clock and a fountain, which they hoped would please the Indian prince. Each of them also took some wares on their own account, with Giovanni Loredan taking some Florentine cloth, a piece of which he sold along the way to pay for expenses. In order to raise his share of the needed funds, Giovanni also accepted money in the colleganza from his father-in-law, Alberto Calli, who invested 6 ducats. Having made their way to Delhi, Giovanni and the other nobles succeeded in pleasing the Indian prince, as he gave them a rich present, which they then invested in a joint purchase of pearls. However, the journey turned out tragically, as Giovanni and two other nobles died in the course of the journey.[25] Giovanni's brother Paolo assumed his dead brother's obligations and continued the journey. On the way home, the pearls were divided among the surviving partners, but Giovanni was not there to make the most of the outcome that he had imagined before the voyage. After the nobles returned home to Venice, Giovanni's father-in-law, an early investor in the colleganza, sued the guardians of Giovanni's young sons to recover not only the value of his investment, but also the usual profits from such a voyage.[26] Despite winning the case, he was almost certainly disappointed when he did not even double his initial investment in what had been projected to be a highly lucrative enterprise. The voyage of the Loredan brothers is one of the most popular anecdotes used by historians to depict the burgeoning of a global economy during that time.[27]

One of the most notorious usurers of the time was Leonardo Loredan (d. 1349), borrowing at interest rates of 65% to 100%.[20] His representatives did not hesitate to put families out of their homes, he battened on war loans, and was arraigned by ecclesiastical courts to answer to charges of aggravated usury, but he always managed to confute the charges by means of gifts, bribery and occult levers.[19] Later, much of his wealth went into building two Loredan palaces in the city.[19]

After the infamous failed 1355 Faliero coup that involved Doge Marino Faliero and his partners, including Filippo Calendario, which attempted to overthrow the republican government and establish a dictatorship, Andrea and Daniele Loredan managed to produce a testimony against Faliero, regarding his secret plots against the ruling class, after which they manipulated the Council of Ten and then led the call for his brutal torture.[20] On the night of 17 April 1355, over the space of a few hours, they had Faliero questioned, framed, tortured and beheaded. Additionally, ten of his accomplices were hanged on display from the balcony of the Doge's Palace.[19]

Marco Loredan, who lived in the 14th century was elected as Procurator of Saint Mark, one of the highest political positions in the Venetian Republic, and was one of the electors of Doge Andrea Dandolo. Contemporary to him are Paolo Loredan (d. 1372), a military general who distinguished himself in the highest military positions of land and sea, and Alvise Loredan, who also became Procurator of Saint Mark.[7]

Giovanni Loredan (lat. Ioannes Lauredanus) served as the Bishop of Capo d'Istria (today Koper, Slovenia) from 1390 until his death on 11 April 1411.[28] From 1354 he was the presbyter of Saint Mark's Basilica, Venice. He was appointed Bishop of Capo d'Istria on 21 November 1390.[28] According to several church chronologies, before that he was also a bishop in Venice, in what was then the Diocese of Castello. It is recorded that in 1391 he dedicated the Church of St. George in Piran. He was buried in the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Koper.[28] In some historical sources he is mentioned under the name of Giacomo or the Slovenian Jakob.[29]

15th century: Political and military rise

[edit]One of the important members of the family in the 15th century was Pietro Loredan (1372–1438), who was three times Captain General of the Sea;[30] in 1416 he conquered several Dalmatian strongholds and later defeated the Ottomans at Gallipoli, capturing fifteen galleys; in 1431 he defeated the Genoese and Milanese in Rapallo, achieving the capture of eight galleys and General Francesco Spinola. Pietro died in 1439.[31] He was buried in the Monastery of St. Helena, and the funeral inscription explicitly indicates poisoning as the cause of his death.[32] Many historians identify the principal to be his long-time rival, Doge Francesco Foscari, whose enmity with the deceased Pietro was well-known.[33] In the popular imagination, the names of the Foscari and Loredan remain linked to a sort of generational feud, partly documented, partly due to certain historiographic forcing; and yet it is undeniable how, in the crucial moments that marked the life of Francesco and his son Jacopo Foscari, a Loredan was always present.[34]

Loredan's letter following the Battle of Gallipoli and addressed to the Doge of Venice has been preserved:

"I, as commander, vigorously attacked the first galley, which put up a stout defence, being excellently manned by courageous Turks who fought like dragons. With God's help I overcame her, and cut most of the said Turks to pieces. Yet it cost me much to save her, for others of their galleys bore down upon my port quarter, raking me with their arrows. Indeed, I felt them; for one struck me in the left cheek, just below the eye, piercing the cheek and nose; and another passed through my left hand. And these were only the serious wounds; I received many others about the body and also in my right hand, though these were of comparatively little consequence. I did not retire, nor would I have retired while life remained to me; but, still righting vigorously, I drove back the attackers, took the first galley and hoisted my flag in her... Then, turning suddenly about, I rammed a galleot, cutting many of her crew to pieces, put some of my own men aboard and again ran up my flag... Their fleet fought on superbly, for they were manned by the flower of the Turkish seamen; but by God's grace and the intercession of St. Mark our Evangelist we at last put them to flight – many of their men, to their shame, leaping into the sea... The battle lasted from early morning till past two o'clock; we took six of their galleys, with their crews, and nine galleots. And the Turks that were on them were all put to the sword, including the admiral and all his nephews and many other great captains... The battle over, we sailed beneath the walls of Gallipoli, bombarding them with missiles and calling on those within to come out and fight; but they would not. So we drew away, to allow the men to refresh themselves and dress their wounds... And aboard the captured vessels we found Genoese, Catalans, Sicilians, Provencals, and Cretans, of whom those who had not perished in the battle I myself ordered to be cut to pieces and hanged... together with all the pilots and navigators, so the Turks have no more of those at present. Among them was Giorgio Calergi, a rebel against your Grace, whom despite his many wounds I ordered to be quartered on the stern of my own galley – a warning to any Christians base enough to take service with the infidel henceforth. We can now say that the power of the Turk in this region has been utterly destroyed, and will remain so for a long time to come. I have eleven hundred prisoners..."

Tenedos, 2 June 1416

Excerpt from: Norwich, John Julius. A History of Venice

Pietro's son Giacomo Loredan was a general who served as Captain of the Gulf and three times as Captain General of the Sea in the Venetian Navy.[35] He defeated the Ottomans in 1464.[9]

Also significant at this time was Alvise Loredan (1393–1466), who became a galley captain at a young age and served with distinction as a military commander, with a long record of battles against the Ottomans, from the naval expeditions to aid Thessalonica, to the Crusade of Varna, and the opening stages of the Ottoman-Venetian war, as well as the Wars in Lombardy against the Duchy of Milan.[36] The Loredans were proponents of Venice's traditional, maritime orientation, and viewed with distrust its expansion on the Italian mainland (the Terraferma), which had brought it into conflict with Milan. Alvise Loredan shared this view, as can be seen from a proposal he brought before the Great Council in February 1442, ordering the governors of Bergamo to demolish its fortifications as a sign of goodwill and trust towards Visconti, following the conclusion of peace with Milan at the Treaty of Cremona.[11] He also served in a number of high government positions, as provincial governor, Savio del Consiglio, and Procuratore de Supra of Saint Mark's Basilica, and was Count of Bergamo and Belluno. He died in Venice on 6 March 1466, and was buried in the Church of Santa Maria dei Servi.[36]

Giorgio Loredan (d. 1475) was an admiral, military general and politician, known for investigating political crimes and scandals as head of the Council of Ten.[37] He was also Count of Zara, Chioggia and Padua.[37]

Antonio Loredan (1420–1482) was captain of Venetian-held Scutari and governor in Split (Venetian Dalmatia), Venetian Albania and the Morea.[38] He is famous for the successful defence of Scutari from Sultan Mehmed II's Ottoman forces led by Hadım Suleiman Pasha.[10] According to some sources, when the Scutari garrison complained for lack of food and water, Loredan told them: "If you are hungry, here is my flesh; if you are thirsty, I give you my blood."[39] He also served as the Captain General of the Sea and is notable for commissioning the Legend of Saint Ursula (1497/98), a series of large wall-paintings by Vittore Carpaccio originally created for Scuola di Sant'Orsola which was under the patronage of the Loredan family.[40]

Giovanni Loredan, Lord of Antiparos built the Castle of Antiparos in 1440 and brought inhabitants to the island at his own expense.[41] He married Maria Sommaripa, of the ruling family of Paros, and they had a daughter, Lucrezia Loredan, Lady of Ios and Therasia.[42]

Andrea Loredan (1455–1499) was an admiral and the Duke of Corfù, best known for his successful exploits against pirates who raged across the Adriatic and the Mediterranean.[43] He fought at sea against famous admirals such as Kemāl Reis, stealing from him multiple boats and destroying many by fire, and Pedro Navarro, whom he managed to wound after six hours of fierce battle in Roccella Ionica near Crotone in 1497. Andrea died on a burning ship while fighting against the Ottomans in the Battle of Zonchio in August 1499.[11]

Antonio Loredan (1446–1514) was the Duke of Friuli, and ambassador to the Papal States, the Kingdom of France and the Holy Roman Empire.[44]

In that same century, Luigi and Giacomo Loredan, both Procurators of Saint Mark, distinguished themselves with important political positions.[7]

Leonardo Loredan, born in 1436 to Gerolamo Loredan di S. Vitale and Donata Donà di Natale, was the first doge of the Loredan family. He had a good classical education, focusing on literature, after which he devoted himself to trade in Africa and the Levant to increase the family's finances, where he made his fortune.[45] In 1461, he married Giustina Giustiniani, of the wealthy branch of S. Moisè, with whom he had nine children: Lorenzo (who became Procurator of St. Mark's), Girolamo (the only one to continue the branch), Alvise, Vincenzo (died in Tripoli in 1499), Bernardo, Donata, Maria (wife of Giovanni Venier, of the branch that gave birth to Doge Francesco Venier), Paola (wife of Giovanni Alvise Venier, descendant of Doge Antonio Venier), and Elisabetta.[46]

Leonardo's political ascent began at the age of nineteen, when he became a lawyer in the "Giudici di Petizion", a magistracy concerned mainly with financial scandals and bankruptcies, for which he had Filippo Loredan as guarantor. During his political career, he held multiple high positions such as chamberlain of the Comùn, wise man of the council, podestà of Padua, and Procurator of Saint Mark's.[47] On 31 March 1495, he was one of the three designated by Doge Agostino Barbarigo to negotiate the alliance between Venice, Pope Alexander VI, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I of Habsburg, the Spanish rulers Ferdinand V and Isabella I and the Duke of Milan Ludovico Maria Sforza (King Henry VII of England also joined), with the aim of countering the military operations of the King of France Charles VIII who had, almost without encountering military resistance, entered Naples in February. The army of the League, led by the Marquis of Mantua Francesco II Gonzaga, in the Battle of Fornovo on 6 July forced the French army to withdraw from Italian territory. In October of the same year, Loredan signed the agreement for the conduct of Niccolò Orsini, count of Pitigliano, to the services of the Republic of Venice as governor general of the land militias for the period of three to four years. In January 1497, Loredan, with the wise man of the Terraferma Lodovico Venier, ratified the surrender of Taranto on behalf of the Doge.[46]

16th century: The Ottomans and the League of Cambrai

[edit]

On the death of Doge Agostino Barbarigo (20 September 1501), Leonardo Loredan was one of the designated candidates in the election of the new doge, which began on 27 September and ended on 2 October with Loredan coming out first with 27 votes in the sixth hand of the first ballot.[48] The election was successful thanks to his and his wife's influential relations and the sudden death of the most popular opponent, the wealthy procurator Filippo Tron, son of Doge Nicolò Tron.[49] Leonardo became the 75th Doge of the Venetian Republic and his dogeship is considered one of the most important in the history of Venice.[50][51][52]

Ottoman-Venetian War

[edit]At the time of his accession to the dogeship, Venice was engaged in the second Ottoman-Venetian war,[53] and Leonardo had lost his cousin Andrea Loredan, a naval officer, in the disastrous Battle of Zonchio.[54] The war proceeded badly on land too, with the Venetians losing considerable territory.[55] This included the strategic city of Modon, which was the site of a bloody battle involving hand-to-hand combat, followed by the beheading of hundreds of Venetians following the Turkish victory.[55] The war took a heavy toll on the Venetian economy, and in 1502/1503 Loredan agreed a peace treaty with the Ottomans.[56] He was helped in negotiations by Andrea Gritti, a Venetian who had been conducting trade in Constantinople and would later become Doge of Venice himself.[57]

War of the League of Cambrai

[edit]Upon the death of Pope Alexander VI in 1503, Venice occupied several territories in the northern Papal States.[49] When Julius II was elected as Alexander's eventual successor, the Venetians expected their seizure of papal territory to be tacitly accepted, as Julius had been nicknamed Il Veneziano for his pro-Venetian sympathies.[58][59] But instead the new Pope excommunicated the Republic and demanded the land be returned.[49] The Republic of Venice, although willing to acknowledge Papal sovereignty over these port cities along the Adriatic coast and willing to pay Julius II an annual tribute, refused to surrender the cities themselves.[60] In 1508, Julius formed an alliance called the League of Cambrai, uniting the Papal States with France, the Holy Roman Empire and several other Christian states.[49][61]

The Doge's problems did not end in Europe. In 1509, the Battle of Diu took place, in India, where the Portuguese fleet defeated an Ottoman and Mameluk fleet, which had been transferred from the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea with Venetian help. The defeat marked the end of the profitable Spice trade, which was bought by Venetians from the Mameluks in Egypt and in turn monopolised its sale in Europe, reaping great revenues from it.[62]

After losing to the league's forces at the Battle of Agnadello, Venice found its holdings in Italy shrinking drastically.[63] Soon Padua, Venice's most strategically vital Terraferma holding, had fallen, and Venice itself was threatened. Loredan united the population, calling for sacrifice and total mobilisation.[64] Padua was retaken, though Venice was still forced to accept a reluctant peace, following which it joined the Pope as only a junior ally in his new war against the French.[65] The alliance was on the verge of victory, but a dispute arose over territory. Emperor Maximilian refused to surrender any Imperial territory, which in his eyes included most of the Veneto, to the Republic; to this end, he signed an agreement with the Pope to exclude Venice entirely from the final partition. When the Republic objected, Julius threatened to reform the League of Cambrai. In response, Venice turned to Louis; on 23 March 1513, a treaty pledging to divide all of northern Italy between France and the Republic was signed at Blois.[66] Under this alliance with the French King Louis XII, the Venetians achieved a decisive victory over the Papal States, and were able to secure back all the territories they had lost.[67] In addition, the Papacy, namely Pope Leo X, a Medici, was forced to repay many outstanding debts to the Loredan family totalling approximately 500,000 ducats, an enormous amount of money.[68]

Around this time, Leonardo's cousin Andrea Loredan, known as a collector of art, commissioned the Ca' Loredan Vendramin Calergi, a palace on the Grand Canal, to designs by Mauro Codussi.[69] The palace was paid for by the doge. Andrea also commissioned and paid for the choir of the church of San Michele in Isola, also designed by Codussi. In 1513, during the War of the League of Cambrai, he had to accept the role of quartermaster-general for the army, and he died in the Battle of La Motta in the same year, beheaded by two soldiers who fought over his body.[11]

The end of the war and the behavior of the doge, who perhaps thought he should enjoy the last years of his life rather than dedicate them to the administration of the state, led to a certain frivolity in Venetian society.[70] Financial scandals were the order of the day and many public offices were bought at disproportionate prices rather than obtained on merit. In this period the doge bought titles and offices for children and relatives, making the most of his influence.[70]

Despite Loredan's wishes, he could not lead this pleasant life for long as he began to experience health problems. Around the first days of June 1521 his health began to deteriorate and soon gangrene developed in his leg. Any intervention was useless and the gangrene spread, killing him in the night between 20 and 21 June.[71] It is said that, to warn the councilors and regents of the state, the news of his death was silenced by the doge's own son and was communicated only in the late morning.[70]

Interestingly, the commercialism and non-exemplary behaviour of his final years did not escape the watchful eye of the Inquisitors of the Dead, a magistracy created after the death of Francesco Foscari, charged with investigating the final "account" of the doge. Perhaps the trial was artfully mounted for political purposes but certainly there were incriminating motives, because the heirs of the doge, despite being defended by the lawyer Carlo Contarini, one of the best of the time, were sentenced to a hefty fine of 9,500 ducats.[71]

Leonardo Loredan died in Venice on 22 June 1521. The death, which occurred between eight and nine, was kept secret until sixteen at the behest of the children who, during their father's agony, had no regard for transporting furniture and objects from the doge's apartment to their residence. As is customary, the body was subjected to embalming practices. On the morning of 23 June, after the body was moved to the Piovego room of the Doge's Palace, the coffin was closed. At the solemn funeral the eulogy was read by the scholar Andrea Navagero, and Pietro Bembo, then abbot and secretary of Pope Leo X, was also present.[46][70]

Loredan died "with great fame as a prince".[72] He was interred in the church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, in a simple tomb with a celestial marble headstone without inscription, placed above the steps of the main altar and now no longer existing.[73] In about 1572, and after some disputes between the Loredan heirs and the friars of the church, a funeral monument was erected for him, divided into three parts and adorned with Corinthian columns in Carrara marble, placed to the left of the main altar, with architecture by Girolamo Grappiglia, and adorned with an extremely lifelike statue, an early work by the sculptor Girolamo Campagna, which depicts him in the act of "getting up and boldly throwing himself in defence of Venice against Europe conspired in Cambrai".[74] On its right was the statue of Venice with sword in hand and on the left that of the League of Cambrai, with the shield adorned with the heraldic coats of arms of the opposing powers (these, and the others in the monument were done by Danese Cattaneo, a pupil of Sansovino).[75][76]

In the dramatic events of the early 16th century, Loredan's Machiavellian plots and struggles against the League of Cambrai, the Ottomans, the Mamluks, the Pope, the Republic of Genoa, the Holy Roman Empire, the French, the Egyptians and the Portuguese saved Venice from downfall.[68]

Numerous portraits of Doge Leonardo Loredan have been painted, most famous of which are those by Giovanni Bellini and Vittore Carpaccio.[77][78][79] The Panegyricus Leonardo Lauredano was created in 1503 in his honour.[80][81][82]

Leonardo Loredan was succeeded by Doge Antonio Grimani in 1521, who was married to Leonardo's sister, Dogaressa Caterina Loredan: “The Loredanian tradition for patriotism and nobility was handed on in the gracious personage of Dogaressa Caterina Loredan, sister of Doge Leonardo Loredan – the Consort of his successor Doge Antonio Grimani.”[72] They had several children, including cardinal Domenico Grimani.[83]

Taddea Caterina Loredan, Duchess of the Archipelago, known as "a lady of wisdom and great talent",[13] was the wife of Francesco III Crispo, who was mentally ill and was known as the "Mad Duke".[13] Francesco attacked her in August 1510; Taddea tried to escape from him, and she fled to the castle of her cousin Lucrezia Loredan, Lady of Ios and Therasia, where Francesco had followed her a day later and attacked her again, on 17 August 1510, now murdering her.[13] Their son John IV Crispo became the next Duke of the Archipelago in 1517, after a regency period during which he was still too young to rule. A 1908 book by historian William Miller titled "The Latins in the Levant, a History of Frankish Greece" indicates that the regent of the Duchy from 1511 to 1517 was Taddea's brother Antonio Loredan.[13]

In 1535, Venice ceded the town of Barban in Istria (today part of Croatia) to the Loredan family, which had acquired it in an auction, as a heritable possession. The family made it their summer residence.[84]

In 1536, the Loredan family acquired what would soon become the Palazzo Loredan in Campo Santo Stefano. Before the restoration by the architect Antonio Abbondi, it was a group of adjacent buildings, in the Gothic style, belonging to the Mocenigo family.[85] The purchased buildings were substantially restored and made into a single building for the residence of the Loredans of Santo Stefano.

Marco Loredan (1489–1557) was a senator and politician, as well as Count of Brescia, Feltre, Rovigo, Salò and Famagusta, presiding over a time of famine and poverty following the War of the League of Cambrai.[15]

Marco Loredan (d. 1577) was a priest and senator who was appointed by Pope Julius II as the Bishop of Nona (today Nin, Croatia), a position which he held from 1554 to 1577.[86] He was also appointed by Pope Gregory XIII as the Apostolic Administrator and Archbishop of Zara (today Zadar, Croatia), where he stayed from 1573 until his death on 25 June 1577.[87]

Pietro Loredan, born in 1482, became the 84th Doge of Venice and the second doge that the Loredan family gave. He was the third son of Alvise di Polo di Francesco Loredan, and his mother, Isabella Barozzi, came from one of the oldest Venetian noble families. Pietro had an intense but not necessarily prestigious political career, which he accompanied with the care of commercial interests according to the family tradition. Pietro married Maria Pasqualigo, and then Maria Lucrezia di Lorenzo Capello, with whom he had a son, Alvise Loredan (1521–1593), who continued the lineage with numerous offspring.[8]

Present in 1509 and in 1510 in the defense of Padua and Treviso, he made his debut in public life in 1510 as a sopracomito. In April 1511 he was elected a Senator, and he intervened in the Senate, asking for the reduction of the sum that the Jews had to pay for their "conduct" and ruled in favor of a league with France, also willing to sell Cremona and Ghiara d'Adda in exchange for other territories. In 1513 he left again to defend Padua and Treviso and, available for military roles, he offered to fill the positions of administrator of the Stradioti and the administrator of Adria. He refused his appointment as consul in Alexandria in 1516, when he intensified his entrepreneurial activity: in 1517 Pietro, together with his brothers, armed a ship to transport pilgrims to the Holy Land and the following year he set up a market galley on the Alexandria route.[88]

Business did not, however, distract him from public service, as evidenced by the various candidacies and the appointment in the College of the Twenty Wise Men, while his financial fortune allowed him to enter the committee of guarantors of Banco Priuli. In 1545 he was one of the nine electors of Doge Francesco Donà; between 1546 and 1549 he ran several times for the Council of Ten, in which, after another stint in the Senate (1549), he entered at the beginning of 1550, becoming its head. Later in the year he became ducal councilor for the Dorsoduro district. In the 1550s, Pietro consolidated his personal prestige, sat assiduously in the Senate, in the Council of Ten, as well as in the Signoria as ducal councilor. In 1559 he was included among the forty-one electors of Doge Girolamo Priuli.[89]

On 29 November 1567 he was elected doge, which came as a surprise for him. "A man of 85 years, but very prosperous.", wrote of him the papal nuncio Giovanni Antonio Facchinetti, who would later become Pope Innocent IX.[90] Considered a figure of little political importance, his dogeship was considered the most suitable because it was transitory and politically harmless. Religious and morally upright, educated, and of uncommon wisdom, Pietro was reluctant at the beginning, but in the two and a half years of his reign showed recognized qualities of balance and prudence.[8]

Pietro Loredan died on 3 May 1570. On the 7th, the state funeral was organised in San Marco, instead of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, due to bad weather. Pietro's body was carried in the cloister of S. Giobbe and buried in the family ark.[8]

Doge Pietro Loredan was portrayed in the ducal palace by Domenico Tintoretto and the painting placed in the Senate room, and by Jacopo Tintoretto for the one in the Scrutinio room.[91]

In 1581 the Loredan family, namely the heirs of Andrea Loredan, sold the famous Palazzo Loredan Vendramin Calergi for 50,000 ducats to Eric II, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg who took loans to afford it.[85]

In 1598, an incident occurred which resulted in an urban legend known as The Ghost of Fosco Loredan.[92] In a burst of anger resulting from jealousy of his wife Elena who attracted many suitors, in this case her cousin of the Mocenigo family, Fosco Loredan murdered her at Campiello del Remèr by decapitating her, and was then ordered by her uncle, Doge Marino Grimani, to walk to Rome while carrying her disfigured body on his back to ask for the Pope's forgiveness, as he was the only one who could grant it to a noble of the rank of Loredan.[93] After hearing the story, Pope Clement VIII did not want to see him, and, out of desperation, Fosco escaped the guards who were going to imprison him and went back to Venice, where he drowned himself in the Grand Canal. Supposedly, on the anniversary of his wife's killing, his ghost can be seen wandering the streets of Venice at night searching for peace, the peace he lost in the burst of anger on the night he tragically murdered his young wife.[94]

17th century: Opera and the Accademia

[edit]

Giovanni Francesco Loredan, born in 1607, was a writer and politician. He was born in Venice as the son of Lorenzo Loredan and Leonora Boldù. When both of his parents died while he was very young, he was raised by his uncle Antonio Boldù and had as his teacher Antonio Colluraffi.[95][96]

He divided his youth between hard study and an extravagant lifestyle.[97] He attended the classes of renowned Aristotelian philosopher Cesare Cremoni in Padua and began, before 1623, to gather around him the group of scholars who then formed the Accademia degli Incogniti, also called the Loredanian Academy.[98] As founder of the Accademia degli Incogniti and a member of many other Academies, he had close contact with almost all the scholars of his time.[99] He and his circle played a decisive role in the creation of modern opera.[100][101] In addition to literary activity, he also took part in public affairs.[102] At twenty he was recorded in the Golden Book, but his career began quite late: in September 1632 he was elected 'Savio agli Ordini' and in 1635 he was Treasurer of the fortress of Palmanova. On his return he reorganized the Accademia degli Incogniti (1636) and, in 1638, despite attempts to avoid it, he was obliged, as the only descendant of his branch, to contract marriage with Laura Valier.[103] He was then Provveditore ai Banchi (1640), 'Provveditore alle Pompe' (1642), and in 1648 he made the leap to the rank of avogador del Comùn that he held several times (1651, 1656 and 1657) and 'Provveditore alle Biave'(1653).[104] He subsequently joined the offices of the State Inquisitor and became a member of the Council of Ten. In 1656 he entered the Minor Consiglio, that is, among the six patricians who, together with the doge, composed the Serenissima Signoria. However, he may then have been pushed out of office, as in the following years he no longer held important positions. In 1660 he was a Provveditore in Peschiera. The following year (13 August 1661) he died.[105]

Dogaressa Paolina Loredan was the daughter of Lorenzo Loredan and wife of Doge Carlo Contarini, whom she married on 22 February 1600 in the Church of San Polo. She was an "immensely stout woman and incredibly plain-looking", and therefore she decided she would not appear in public due to fear of being mocked by the populace.[106] On the façade of the Church of San Vitale, Giuseppe Guoccola sculptured the busts of Doge Carlo and Dogaressa Paolina Loredan, placed there in gratitude of their noble bequests to the clergy.[106]

Interestingly, near the Palazzo Contarini-Sceriman and the nearby bridge, Leonardo Loredan (d. 1675) was found dead in a boat. The unexplained death was the source of many rumors, claiming accidental death, murder by relatives, or murder by the Inquisitors of the Republic.[107]

In the second half of the century, his son Francesco Loredan (1656–1715) is notable as he was the Venetian ambassador to Vienna during the Treaty of Karlowitz peace negotiations.[11][108]

18th century: Wealth, Enlightenment and the Republic's decline

[edit]In June 1715, at the end of his last assignment, as a reformer at the University of Padua, Francesco Loredan fell ill and after twenty-two days he died, in the Palace of Santo Stefano, on 10 July 1715. He remained unmarried, and left a very respectable inheritance, increased over the years, despite the huge expenses incurred for the embassy, and consisting of properties in Venice and vast land holdings, embellished with prestigious manor houses, in the Venetian area, around Treviso and Padua, in the Veronese area and in the territories of Rovigo and Polesine, to his brother, Giovanni, also unmarried, and to his nephews, children of his brother Andrea.[108]

Francesco Loredan, born in 1685, was the 116th Doge of Venice and the third and last of the Loredan family. He served as Doge from 18 March 1752, until his death on 19 May 1762. Loredan was elected doge on 18 March 1752 but the announcement was made on 6 April, postponed because of Easter.[109] By this point, the dogal figure had lost nearly all his power and he quickly adapted to this new situation. As Giacomo Nani wrote in 1756, Loredan was able to face the burdens of becoming doge and exercising the office because his family was one of those of the "first class", that is, "very rich" families.[110] Prodigal and generous, he was described "father of the poor" in two paintings by Pietro Longhi.[111] He did not have a particular interest in culture and had a limited library showing only a certain activism in the artistic field; in addition to being portrayed by minor painters such as Bartolomeo Nazzari and Fortunato Pasquetti, he designed the reconstruction of the commercial maps of territories and countries in the Sala dello Scudo in the ducal palace and the portraits of the last forty-six doges in the Sala dello Scrutinio.[111] He also had Giuseppe Angeli fresco part of the noble floor of the family palace in S. Stefano. However, his more constant interest than himself was the management of the family estate, which at the time included numerous palaces and vast land holdings. One of the biggest issues in domestic politics at the time was the clash between the conservatives and the reformers. The latter wanted to substantially reform the Republic and sought to build internal reforms. The conservative pressure groups were able to block these plans and imprisoned or exiled the reformist leaders, such as Angelo Querini, an important figure of the Venetian Enlightenment. The Doge did not want to show favour to one side or the other, so he remained totally passive and limited his support to making it easier for the winning side, thereby losing his chance to change the fate of the dying republic.[111] By impeding the development of the reformist ideas, he possibly caused the small economic boom which started around 1756 with the outbreak of the Seven Years' War. The neutrality of the Republic during this time allowed the merchants to trade in huge markets without competitors. The French defeat even allowed Venice to become the biggest market for eastern spices.[111]

Interestingly, in 1752, Francesco offered the Palazzo Loredan dell'Ambasciatore as a residence for the ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire, and the first Imperial ambassador to live there was Count Philip Joseph Orsini-Rosenberg. In 1759, Loredan was awarded the Golden Rose by Pope Clement XIII, becoming the first and only doge to obtain the award.[112]

At one point the Doge, who was old and tired by then, seemed about to die but recovered and lived for another year, until his death on 19 May 1762. The funeral took place on 25 May, and he was buried in the basilica of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, in Leonardo Loredan's dogal tomb.[113] The funeral cost an impressive sum of around 18,700 ducats, and was paid for by Francesco's brother Giovanni.[114][111]

Interestingly, the famed author and adventurer Giacomo Casanova was locked in the notorious lead chambers under Francesco Loredan's government in 1755 for suspicious activities, from which he managed his spectacular escape.[115]

During this time, the Loredan family was incredibly wealthy and owned numerous palaces.[111]

The main line of the family branch of Santo Stefano ended in 1750 with Andrea di Girolamo Loredan who died young, and the branch became extinct in 1767 with the death of Giovanni Loredan, brother of Doge Francesco.[111]

19th century: After the fall of Venice

[edit]After the fall of the Republic of Venice in 1797, some branches of the family were named on the basis of Venetian toponyms: San Luca, San Giovanni in Bragora, San Pantaleone etc.[116]

Antonio Francesco di Domenico Loredan held the title of count in the Austrian Empire, and his brothers were also listed in the official list of nobles.[117][118]

Teodoro Loredan Balbi (Krk, 7 November 1745 - Novigrad, 23 May 1831) was the last Bishop of Novigrad, a position which he held from 1795 until his death on 23 May 1831.[29] He was ordained a priest in 1768. His uncle, the Bishop of Pula, Giovanni Andrea Balbi, appointed him a canon scholastic, prosinodal examiner and inquisitor in his diocese.[119] In 1795 he received his doctorate in theology from the University of Padua, and in the same year Pope Pius VI appointed him as Bishop of Novigrad. Sudden political changes caused by the Napoleonic Wars soon followed: the collapse of the Venetian Republic in 1797, a brief change in Austrian and French rule, and the eventual establishment of Austrian rule in Istria after the Congress of Vienna in 1815.[29] Although he did not get involved in the political events of the time, Napoleon's authorities detained him for 10 months in Venice after a trial, where he experienced all sorts of humiliations. After returning to the seat, he was for a time the only bishop in Istria and, under the authority of the Holy See, he visited the dioceses of Poreč and Pula.[29] At the suggestion of Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, Pope Leo XII abolished the Diocese of Novigrad in 1828, which became part of the Diocese of Trieste, but, according to the Pope's order, only after Teodoro's death. As a bishop he sent three letters to the Holy See, in 1798, 1802 and 1807; in them he reported that in the diocese there were one cathedral and one choir church, 17 parishes, and many fraternities; that he opened a seminary and a pawnshop, founded a canonry of theologians and penitents, etc. He was buried in the church of St. Agatha in Novigrad, and his remains were transferred in 1852 to the bishop's tomb in the cathedral.[29]

20th century: Villas and wineries

[edit]

In the 1950s, Count Piero Loredan, descendant of Doge Leonardo Loredan, founded the Conte Loredan Gasparini winery. He chose the territory of Vignigazzu to establish his home in a grand Palladian villa - The Villa Loredan at Paese.[120] The winery is located in Venegazzù di Volpago del Montello, in the Veneto region, in the heart of the Marca Trevigiana, an area famous for the production of wines since the 16th century.[120]

In the 1960s, Countess Nicoletta Loredan Moretti degli Adimari founded the Barchessa Loredan winery, located in Selva del Montello, within a 16th-century Palladian barchessa. The Barchessa Loredan is a magnificent example of Palladian architecture. The noble residence was built in the 16th century; originally it was part of a vast complex which also included a large villa destroyed in 1840. The imposing Barchessa remains of the original complex, with the entrance gates and part of the surrounding wall. The building consists of nine arches with a volute keystone and framed by Doric pilasters supporting a molded entablature, which extends over the entire ground floor. Above the portico rises the first floor, with a very large attic, perfectly restored, in which the most significant memories of the Loredan family are preserved.[121]

In the 1980s, after the death of her husband Antonio Rizzardi, Countess Maria Cristina Rizzardi Loredan found herself managing the Guerrieri Rizzardi winery, based on Lake Garda, which she expanded with new vineyards and wines, also applying the concept of ‘Cru’ as a mark of quality restricted to a well-defined vineyard.[122] She then became President of the Garda Oil Protection Consortium in 1984, and obtained the recognition of the extra virgin olive oil in Garda DOP. In 2010 she was awarded with the Order of Merit for Labour by the President of Italy.[122]

Heraldry

[edit]Coat of arms

The coat of arms of the Loredan family features a shield of yellow (top) and blue (bottom) with six laurel (or rose) flowers pictured on it; three in the yellow and three in the blue area. On top of the crest stands the corno ducale, the ceremonial crown and well-known symbol of the Doge of Venice.[123] It is displayed on multiple buildings and palaces across the territories previously held by the Republic of Venice; from the Veneto and Friuli, Istria and Dalmatia, and in the more distant possessions such as the Ionian Islands and Crete. In Venice, it is even carved into the Rialto Bridge and the façade of St. Mark's Basilica.[124]

-

Loredan crest on the Panegyricus Leonardo Lauredano, 1503

-

A parchment of Doge Leonardo Loredan, 1504

-

Loredan crest at Porta San Bortolo in Rovigo

-

Crest on the Palazzo Loredan a San Cancian

-

Loredan crest on the Ca' Loredan Vendramin Calergi (detail)

Motto

The beautiful façade of the Ca' Loredan Vendramin Calergi made of Istrian stone holds the Latin inscription: NON NOBIS DOMINE.[124] The verse is derived from the Old Testament (Psalm 115:1) and was the beginning of a famous motto inscribed onto the war flag of the Knights Templar: "Nōn nōbīs, Domine, nōn nōbīs, sed nōminī tuō dā glōriam" (KJV: "Not unto us, O Lord, not unto us, but to thy name give the glory."). The verse symbolised the gratitude and humility of the Templars who, during the Crusades, fought for the glory of God and not for personal gain.[125] It is known that Andrea Loredan, the commissioner of the palace, was close to the ideas and legacy of the Templars, so the biblical verse subsequently became the motto of the Loredan family as a whole.[126] Due to his interest in the history of the Templars, it is even believed that his palace was one of the meeting places of the Order of Venice. Andrea, however, was not only a military general, but also a humanist protector of the arts and, in fact, he put considerable energy and capital into the palace to obtain a dwelling worthy of his value and the dignity of his family. The oak leaves around the inscription represented in Latin tradition the defender of the city, that is, one who is committed to the public good, a theme much loved by the Venetian nobility of the time. With this inscription, Andrea Loredan almost seems to want to conceal his incredible wealth, thus displaying a strong sense of humility and devotion to the Lord.[127] The essence of the Loredan motto is, in fact, a display of piety and humility coming from a very powerful family.[124]

Titles

[edit]

Throughout history, members of the Loredan family held numerous noble and political titles, some of which include:

Genealogy

[edit]It is worth noting that all of the cadet branches most likely share a common ancestor, presumably Marco Loredan, as he was ascribed to the Great Council of the Republic in 1080, according to the 16th-century philosopher Jacopo Zabarella.[2][3]

Note: The genealogical trees were constructed mainly from information provided in the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani.

Note: The only complete genealogical tree is that of the branch of Santo Stefano; genealogical trees of other branches are partial and do not feature recent members.

Santo Stefano

| House of Loredan-Santo Stefano | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note: The branch of Santo Stefano is also known as the branch of San Vidal (San Vitale).[e]

Note: There are some generations missing between Girolamo Loredan (1468–1532) and Francesco Loredan (17th century).

Note: Giustina Giustiniani (d. 1500), the wife of Doge Leonardo Loredan (1436–1521), is also known as Morosina Giustiniani.

Note: Caterina Loredan, Dogaressa of Venice, is featured in the family tree as the daughter of Gerolamo Loredan (d. 1474) and Donata Donà because, in some sources, she is mentioned as the sister of Doge Leonardo Loredan (1436–1521), although she may have been a daughter of Domenico Loredan.

Interestingly, near the Palazzo Contarini-Sceriman and the nearby bridge, Leonardo Loredan (d. 1675) was found dead in a boat. The unexplained death was the source of many rumors, claiming accidental death, murder by relatives, or murder by the Inquisitors of the Republic.

Andrea Loredan (d. 1750) died young, thus ending the male (agnatic) line of the branch of Santo Stefano.

San Pantaleone della Frescada

| House of Loredan-San Pantaleone della Frescada | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note: Alvise Loredan and Elena Emo had many children,[8] but only Elisabetta Loredan Foscari is featured in the family tree.

Pietro Loredan (1482–1570) reigned as the 84th Doge of Venice from 1567 until his death in 1570.[8]

San Cancian

| House of Loredan-San Cancian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note: In the Venetian language, Pietro Loredan (1372–1438) was known as Piero Loredan.[f]

Note: Besides the four sons and a daughter listed in the tree, Lorenzo Loredan and Marina Contarini had two other sons, Bortolo and Piero, but they died at childbirth.[44]

Santa Maria Formosa

| House of Loredan-Santa Maria Formosa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note: Giacomo Loredan (1396–1471) and Beatrice Marcello had several children,[33] although only Antonio Loredan and Luca Loredan are featured in this genealogical tree.

Note: Antonio Loredan (1420–1482) and Orsola Pisani had many children,[128] although only three sons (Giovanni, Marco, Jacopo) are featured in this genealogical tree.[11][129]

Santa Maria Nova