John Habgood

John Habgood | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of York | |

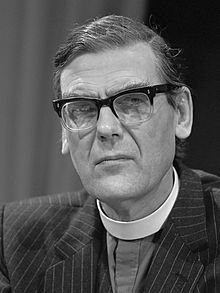

Habgood in 1981 | |

| Province | Province of York |

| Diocese | Diocese of York |

| Installed | 18 November 1983 |

| Term ended | 1995 |

| Predecessor | Stuart Blanch |

| Successor | David Hope |

| Other post(s) | Bishop of Durham (1973–1983) |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1954 |

| Consecration | 1973 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Stapylton Habgood 23 June 1927 Wolverton, England |

| Died | 6 March 2019 (aged 91) York, England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal | |

| In office 8 September 1995 – 3 October 2011 | |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Spiritual | |

| In office 1973–1995 | |

John Stapylton Habgood, Baron Habgood, PC (23 June 1927 – 6 March 2019)[1] was a British Anglican bishop, academic, and life peer. He was Bishop of Durham from 1973 to 1983, and Archbishop of York from 18 November 1983 to 1995. In 1995, he was made a life peer and so continued to serve in the House of Lords after stepping down as archbishop. He took a leave of absence in later life, and in 2011 was one of the first peers to explicitly retire from the Lords.

Personal life

[edit]Habgood was born in Wolverton, Buckinghamshire, on 23 June 1927, the son of Dr Arthur Henry Habgood and his wife Vera.[2][3] He was educated at Eton, King's College, Cambridge and Ripon College Cuddesdon. A University Demonstrator in Pharmacology from 1950, he became a fellow of King's College, Cambridge in 1952.[4] Also in 1952, he was awarded a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree for his thesis titled "Hyperalgesia: an electro-physiological approach".[5]

In 1961 Habgood married Rosalie Mary Anne Boston (died 2016); he had two daughters and two sons, including Francis Habgood, formerly Chief Constable of Thames Valley Police.[3]

Habgood had Alzheimer's disease in his later years, and died at a care home in York on 6 March 2019, at the age of 91.[2]

Early ministry

[edit]Habgood was ordained in the Church of England as a deacon in 1954 and as a priest in 1955.[6] From 1954 to 1956, he was a curate at St Mary Abbots Church, Kensington, London.[7] From 1956 to 1962 he was Vice-Principal of Westcott House theological college in Cambridge. From 1962 to 1967 he was Rector of St John's Church, Jedburgh. In 1967 he became Principal of Queen's College, Edgbaston, a theological college, until his appointment to the episcopate.[3]

He was consecrated a bishop and appointed as Bishop of Durham in 1973.[8] He was passed over by Margaret Thatcher for appointment as Bishop of London in 1981.[9]

Archbishop of York

[edit]Habgood was elevated to Archbishop of York on 18 November 1983.[10] The other name put forward for the Prime Minister's consideration was that of former England cricketer, David Sheppard, by then Bishop of Liverpool. Sheppard's socialist views – he later sat in the Lords as a Labour Peer – did not commend him to Thatcher.[11] As an archbishop, Habgood was made a Privy Counsellor in 1983.[12]

As Archbishop of York, Habgood was seen as a leader in keeping more conservative Anglicans within the church during growing divisions over the issue of women's ordination to the priesthood.[13] He supported the ordination of women to the priesthood, arguing that God is neither male nor female.[14] He also supported accommodating those who did not, and so introduced provincial episcopal visitors to provide pastoral care and oversight to laity, clergy, and parishes who could not accept women priests.[14] Habgood retired as Archbishop of York in August 1995.

Canterbury

[edit]When Robert Runcie announced his retirement as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1990, Habgood was regarded as one of the favourites to succeed him. The religious journalist Clifford Longley described him as "the outstanding churchman of his generation", although noting that Habgood had described himself as too old.[15] As preparations for the selection of the new archbishop began, Habgood gave a television interview stating that he was interested in being considered as "if I believed that this is what the church really wanted and if I believed that this is what God really wanted I would be under a strong obligation to say yes." At the same time it was reported that Habgood was not popular among those close to the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, who would make the actual recommendation to the Queen.[16] Habgood had also attracted criticism inside and outside the Church for his behaviour during the 1987 Crockford's Clerical Directory preface controversy.

At the beginning of May a report in the Sunday Correspondent stated that four candidates were under active consideration: Habgood, David Sheppard (Bishop of Liverpool), Colin James (Bishop of Winchester) and John Waine (Bishop of Chelmsford).[17] Habgood declined to take up the automatic place he could have had on the Crown Appointments Commission, which would select the two names to be given to the Prime Minister.[18] He was endorsed in a leader in The Times on 10 July 1990.[19] On 25 July it was announced that the next Archbishop of Canterbury would be George Carey, the Bishop of Bath and Wells. Habgood described him as "a good choice", adding that "there is a little human bit in anybody that likes the top job, but that is a very small part in my feelings. In my heart of hearts I didn't really want the job. If it had come five years ago I might have thought differently but you slow up and it is an enormously tiring job."[20]

House of Lords

[edit]From his appointment as Bishop of Durham in 1973 to his retirement as Archbishop of York in 1995, Habgood sat in the House of Lords as a Lord Spiritual. This was due to the senior rankings of the two bishoprics in the Church of England, which each granted an automatic seat in the Lords. He voted against Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 which banned local authorities from "promoting homosexuality" and state schools from teaching the "acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship": it was later repealed in 2000 in Scotland and in 2003 in the rest of the UK.[21]

Habgood was created a life peer as Baron Habgood, of Calverton in the County of Buckinghamshire on 8 September 1995,[22] allowing him to continue to sit in the House of Lords as a Lord Temporal. He sat as a crossbencher, rather than join a political party.[14] Later in his life he ceased attending the Lords and took leave of absence; on 3 October 2011 he became one of the first two peers to formally and permanently retire from membership under a newly instituted procedure[23] that was created before permanent retirement achieved full legal recognition under the House of Lords Reform Act 2014.

Religion and science

[edit]Habgood was a member and past president of The Science and Religion Forum.[24] He wrote in this area, e.g., his book Truths in Tension: New Perspectives on Religion and Science (1965). Another example of his work in this area is "Faith, Science and the Future: the Conference Sermon", which was given at the World Council of Churches' conference on Faith, Science and the Future held on the MIT campus (12–24 July 1979).[25] In 2000, he delivered the Gifford Lectures on The Concept of Nature at the University of Aberdeen.[26] An early 21st-century example is his review of Ronald L. Numbers's book The Creationists, which Habgood titled "The creation of Creationism: Today's brand of Protestant extremism should worry theologians as well as scientists".[27]

Books

[edit]- Religion and Science (1964; 1965 U.S. publication retitled to Truths in Tension: New Perspectives on Religion and Science)

- A Cavendish Professor of Physics and Nobel Laureate, Nevill Mott, has cited this book:

"I am impressed too by the point of view of the present Archbishop of York (John Habgood, Science and Religion, [London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1964]), that to understand the Bible we must try to enter into the belief patterns of the period".[28]

- A Working Faith (1980)

- Church and Nation in a Secular Age (1983)

- Confessions of a Conservative Liberal (1988)

- Making Sense (1993)

- Faith and Uncertainty (1997)

- Being a Person (1998)

- Varieties of Unbelief (2000)

- The Concept of Nature (2002)[29]

Arms

[edit]  |

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Becket, Adam. "Death announced of John Habgood, former Archbishop of York". Church Times. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ a b Hall, John (2023). "Habgood, John Stapylton, Baron Habgood (1927–2019), archbishop of York". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.90000380877. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c "HABGOOD, Baron". Who's Who. A & C Black. Retrieved 24 July 2017.(Subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ University News. The Times (London, England), Wednesday, 19 March 1952; p. 6; Issue 52264

- ^ Habgood, John Stapylton (1952). Hyperalgesia: an electro-physiological approach (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Lord (John Stapylton) Habgood". Crockford's Clerical Directory (online ed.). Church House Publishing. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ Church web site

- ^ New bishop consecrated The Times (London, England), Wednesday, 2 May 1973; p. 20; Issue 58771

- ^ "The Right Reverend Lord Habgood: Archbishop of York of the highest intellectual calibre and integrity, whose liberal views proved unfashionable in the 1980s" Daily Telegraph Obituaries p33 Issue no 50,947 dated Friday 8 March 2019

- ^ Of Choristers – York, The Minster School Archived 25 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Guardian obituary David Sheppard 7 March 2006.

- ^ Court Circular. The Times (London, England), Thursday, 22 December 1983; p. 12; Issue 61719

- ^ "Habgood to retire as Archbishop of York". The Independent. 30 September 1994.

- ^ a b c Webster, Alan (7 March 2019). "Lord Habgood obituary". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ Longley, Clifford (31 March 1990). "Habgood by a head". The Times. p. 10.

- ^ Longley, Clifford (4 May 1990). "Habgood's mitre in the Canterbury ring". The Times. p. 1.

- ^ "Four left in Runcie race". The Sunday Times. 6 May 1990.

- ^ "Bishops to help select archbishop". The Times. 23 June 1990. p. 3.

- ^ "A Sceptic for Canterbury", The Times, 10 July 1990, p. 15.

- ^ "Carey appointment welcomed by Runcie". The Times. 26 July 1990. p. 2.

- ^ "Former Archbishop of York dies aged 91". BBC News. 7 March 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ "No. 54156". The London Gazette. 13 September 1995. p. 12433.

- ^ "Former Archbishop of York retires from House of Lords". The Press. 3 October 2011.

- ^ "Reviews in Science and Religion (Num. 49, May 2007, page 17)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ^ Faith and Science in an Unjust World, World Council of Churches, 1980, ISBN 2-8254-0629-5, pp. 119–122

- ^ "The Gifford Lectures". abdn.ac.uk. University of Aberdeen.

- ^ The Times Literary Supplement 23 July 2008, John Habgood

- ^ page 68 of Margenau, H. (1992). Cosmos, Bios, Theos: Scientists Reflect on Science, God, and the Origins of the Universe, Life, and Homo sapiens. Open Court Publishing Company. co-edited with Roy Abraham Varghese. This book is mentioned in a 28 December 1992 Time magazine article: Galileo And Other Faithful Scientists Archived 25 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ British Library web site accessed 17:08 GMT Friday 13 July 2011

- ^ Debrett's Peerage. 2000.

External links

[edit]- Biography – John Habgood, on the Gifford Lectures site. 2000–2001 lectures are online.

- John Habgood – God debates at Cambridge website

- Contributions in the House of Lords

- "The Untidiness of Integration: John Stapylton Habgood" Archived 25 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Kevin Seybold, Volume 57 Number 2. June 2005. PSCF

- 1927 births

- 2019 deaths

- 20th-century Anglican archbishops

- Alumni of King's College, Cambridge

- Alumni of Ripon College Cuddesdon

- Archbishops of York

- Bishops of Durham

- Crossbench life peers

- Deaths from Alzheimer's disease in England

- Fellows of King's College, Cambridge

- Life peers created by Elizabeth II

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Ordained peers

- Peers retired from the House of Lords

- People educated at Eton College

- People from Milton Keynes

- Principals of Queen's College, Birmingham

- Staff of Westcott House, Cambridge