Foundling Hospital

1753 engraving of the Foundling Hospital building, now demolished | |

1889 map of Bloomsbury, showing the Foundling Hospital | |

| Successor | Thomas Coram Foundation for Children; Ashlyns School |

|---|---|

| Formation | 25 March 1741 |

| Founder | Thomas Coram |

| Founded at | London, Great Britain |

| Dissolved | 1951 |

| Type | Orphanage |

| Legal status | Closed |

| Purpose | "The education and maintenance of exposed and deserted young children" |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 51°31′29″N 0°07′11″W / 51.5247°N 0.1197°W |

Founding Governor | William Hogarth |

Governor | George Frederic Handel |

The Foundling Hospital (formally the Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children) was a children's home in London, England, founded in 1739 by the philanthropic sea captain Thomas Coram. It was established for the "education and maintenance of exposed and deserted young children."[1] The word "hospital" was used in a more general sense than it is in the 21st century, simply indicating the institution's "hospitality" to those less fortunate. Nevertheless, one of the top priorities of the committee at the Foundling Hospital was children's health, as they combated smallpox, fevers, consumption, dysentery and even infections from everyday activities like teething that drove up mortality rates and risked epidemics.[2] With their energies focused on maintaining a disinfected environment, providing simple clothing and fare, the committee paid less attention to and spent less on developing children's education. As a result, financial problems would hound the institution for years to come, despite the growing "fashionableness" of charities like the hospital.[3]

Early history

[edit]Foundation

[edit]

Thomas Coram presented his first petition for the establishment of a Foundling Hospital to King George II in 1735. The petition was signed by 21 prominent women from aristocratic families, whose names not only lent respectability to his project, but made Coram's cause "one of the most fashionable charities of the day".[4] Two further petitions, with male signatories from the nobility, professional classes, gentry, and judiciary, were presented in 1737.[5] The founding royal charter, signed by King George II, was presented by Coram at a distinguished gathering at 'Old' Somerset House to the Duke of Bedford in 1739.[6] It contains the aims and rules of the hospital and the long list of founding governors and guardians: this includes 17 dukes, 29 earls, 6 viscounts, 20 barons, 20 baronets, 7 privy counsellors, the lord mayor and 8 aldermen of the City of London; and many more besides.[7] The building was constructed between 1742 and 1752 by John Deval, the King's Master Mason.[8]

The first children were admitted to the Foundling Hospital on 25 March 1741, into a temporary house located in Hatton Garden. At first, no questions were asked about child or parent, but a note was made of any 'particular writing, or other distinguishing mark or token' which might later be used to identify a child if reclaimed. These were often marked coins, trinkets, pieces of fabric or ribbon, playing cards, as well as verses and notes written on scraps of paper. On 16 December 1758, the hospital governors decided to provide receipts to anyone leaving a child making the identifying tokens unnecessary.[9] Despite this, the admission records show that tokens continued to be left.[10] Clothes were carefully recorded as another means to identify a claimed child. One entry in the record reads, "Paper on the breast, clout on the head." The applications became too numerous, and a system of balloting with red, white and black balls was adopted. Records show that between 1 January 1750 and December 1755, 2523 children were brought for admission, but only 783 taken in. Private funding was insufficient to meet public demand.[11] Between 1 June 1756 and 25 March 1760, and with financial support from Parliament, the hospital adopted a period of unrestricted entry. Admission rates soared to highs of 4,000 per year.[12] By 1763 admission was by petition, requiring applicants to provide their name and circumstances.[13] Children were seldom taken after they were 12 months old, except for war orphans.[14]

On reception, children were sent to wet nurses in the countryside, where they stayed until they were about four or five years old. Due to the fact that many of these nurses lived outside of London it was necessary to involve a network of voluntary inspectors, who were the hospital's representatives.[15] Although the hospital governors had no specific plan for who these inspectors were, in practice it was often local clergy or gentry who performed this role.[16]

At the age of 16, girls were generally apprenticed as servants for four years; at 14, boys were apprenticed into a variety of occupations, typically for seven years. There was a small benevolent fund for adults.[1]

The London hospital was preceded by the Foundling Hospital, Dublin, founded 1704, and the Foundling Hospital, Cork, founded 1737, both funded by government.[17]

The new hospital

[edit]In September 1742, the stone of the new hospital was laid on land acquired from the Earl of Salisbury on Lamb's Conduit Field in Bloomsbury, an undeveloped area lying north of Great Ormond Street and west of Gray's Inn Lane. The hospital was designed by Theodore Jacobsen as a plain brick building with two wings and a chapel, built around an open courtyard. The western wing was finished in October 1745. An eastern wing was added in 1752 "in order that the girls might be kept separate from the boys". The new Hospital was described as "the most imposing single monument erected by eighteenth century benevolence".[18]

In 1756, the House of Commons resolved that all children offered should be received, that local receiving places should be appointed all over the country, and that the funds should be publicly guaranteed. A basket was accordingly hung outside the hospital; the maximum age for admission was raised from two months to 12, and a flood of children poured in from country workhouses. In less than four years 14,934 children were presented, and a vile trade grew up among vagrants, who sometimes became known as "Coram Men", of promising to carry children from the country to the hospital, an undertaking which they often did not perform or performed with great cruelty. Of these 15,000, only 4,400 survived to be apprenticed out. The total expense was about £500,000, which alarmed the House of Commons. After throwing out a bill which proposed to raise the necessary funds by fees from a general system of parochial registration, they came to the conclusion that the indiscriminate admission should be discontinued. The hospital, being thus thrown on its own resources, adopted a system of receiving children only with considerable sums (e.g., £100), which sometimes led to the children being reclaimed by the parent. This practice was finally stopped in 1801; and it henceforth became a fundamental rule that no money was to be received. The committee of inquiry had to be satisfied of the previous good character and present necessity of the mother, and that the father of the child had deserted both mother and child, and that the reception of the child would probably replace the mother in the course of virtue and in the way of an honest livelihood. At that time, illegitimacy carried deep stigma, especially for the mother but also for the child. All the children at the Foundling Hospital were those of unmarried women, and they were all first children of their mothers. The principle was in fact that laid down by Henry Fielding in The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling: "Too true I am afraid it is that many women have become abandoned and have sunk to the last degree of vice [i.e. prostitution] by being unable to retrieve the first slip."[1]

There were some unfortunate incidents, such as the case of Elizabeth Brownrigg (1720–1767), a severely abusive Fetter Lane midwife who mercilessly whipped and otherwise maltreated her adolescent female apprentice domestic servants, leading to the death of one, Mary Clifford, from her injuries, neglect and infected wounds. After the Foundling Hospital authorities investigated, Brownrigg was convicted of murder and sentenced to hang at Tyburn. Thereafter, the Foundling Hospital instituted more thorough investigation of its prospective apprentice masters and mistresses.[19]

Music and art

[edit]

The Foundling Hospital grew to become a very fashionable charity, and it was supported by many noted figures of the day in high society and the arts. Its benefactors included a number of renowned artists, thanks to one of its most influential governors, the portrait painter and cartoonist William Hogarth.[20]

Art

[edit]Hogarth, who was childless, had a long association with the hospital and was a founding governor. He designed the children's uniforms and the coat of arms, and he and his wife Jane fostered foundling children. Hogarth also decided to set up a permanent art exhibition in the new buildings, encouraging other artists to produce work for the hospital. By creating a public attraction, Hogarth turned the Hospital into one of London's most fashionable charities as visitors flocked to view works of art and make donations. At this time, art galleries were unknown in Britain, and Hogarth's fundraising initiative is considered to have established Britain's first ever public art gallery.[21]

Several contemporary English artists adorned the walls of the hospital with their works, including Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, Richard Wilson and Francis Hayman. Hogarth himself painted a portrait of Thomas Coram for the hospital, and he also donated his Moses Brought Before Pharaoh's Daughter. His painting March of the Guards to Finchley was also obtained by the hospital after Hogarth donated lottery tickets for a sale of his works, and the hospital won it. Another noteworthy piece is Roubiliac's bust of Handel. The hospital also owned several paintings illustrating life in the institution by Emma Brownlow, daughter of the hospital's administrator. In the chapel, the altarpiece was originally Adoration of the Magi by Casali, but this was deemed to look too Catholic by the hospital's Anglican governors, and it was replaced by Benjamin West's picture of Christ presenting a little child. William Hallett, cabinet maker to nobility, produced all the wood panelling with ornate carving, for the court room.[1]

Exhibitions of pictures at the Foundling Hospital, which were organised by the Dilettante Society, led to the formation of the Royal Academy in 1768.[1] The Foundling Hospital art collection can today be seen at the Foundling Museum.[22]

Music

[edit]

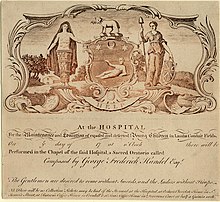

In May 1749, the composer George Frederic Handel held a benefit concert in the Hospital chapel to raise funds for the charity, performing his specially composed choral piece, the Foundling Hospital Anthem. The work included the "Hallelujah" chorus from recently composed oratorio, Messiah, which had premiered in Dublin in 1742. On 1 May 1750 Handel directed a performance of Messiah to mark the presentation of the organ to the chapel. That first performance was a great success and Handel was elected a Governor of the hospital on the following day. Handel subsequently put on an annual performance of Messiah there, which helped to popularise the piece among British audiences. He bequeathed to the hospital a fair copy (full score) of the work.[21]

The musical service, which was originally sung by the blind children only, was made fashionable by the generosity of Handel. In 1774, Dr Charles Burney and a Signor Giardini made an unsuccessful attempt to form in connection with the hospital a public music school, in imitation of the Pio Ospedale della Pietà in Venice, Italy. In 1847, however, a successful juvenile band was started. The educational effects of music were found excellent, and the hospital supplied many musicians to the best army and navy bands.[1]

Relocation

[edit]In the 1920s, the Hospital decided to move to a healthier location in the countryside. A proposal to turn the buildings over for university use fell through, and they were eventually sold to a property developer called James White in 1926. He hoped to transfer Covent Garden Market to the site, but the local residents successfully opposed that plan. In the end, the original Hospital building was demolished. The children were moved to Redhill, Surrey, where an old convent was used to lodge them, and then in 1935 to the new purpose-built Foundling Hospital in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. When, in the 1950s, British law moved away from institutionalisation of children toward more family-orientated solutions, such as adoption and foster care, the Foundling Hospital ceased most of its operations. The Berkhamsted buildings were sold to Hertfordshire County Council for use as a school (Ashlyns School)[23] and the Foundling Hospital changed its name to the Thomas Coram Foundation for Children and currently uses the working name Coram.[24]

Today

[edit]

The Foundling Hospital still has a legacy on the original site. Seven acres (28,000 m2) of it were purchased for use as a playground for children with financial support from the newspaper proprietor Lord Rothermere. This area is now called Coram's Fields and owned by an independent charity, Coram's Fields and the Harmsworth Memorial Playground.[25] The Foundling Hospital itself bought back 2.5 acres (10,000 m2) of land in 1937 and built a new headquarters and a children's centre on the site. Although smaller, the building is in a similar style to the original Foundling Hospital and important aspects of the interior architecture were recreated there. It now houses the Foundling Museum, an independent charity, where the art collection can be seen.[26] The original charity still exists as Coram, registered under the name Thomas Coram Foundation for Children.[27] The surviving Foundling Hospital's Archive covers the years 1739 to 1954. 23% of those records, covering the period of 1739 to 1899 have been digitised, transcribed and made available online (as of October 2024).[28][29]

In fiction

[edit]In the 1840s Charles Dickens lived in Doughty Street, near the Foundling Hospital, and rented a pew in the chapel. The foundlings inspired characters in his novels including the apprentice Tattycoram in Little Dorrit, and Walter Wilding the foundling in No Thoroughfare. In "Received a Blank Child", published in Household Words in March 1853, Dickens writes about two foundlings, numbers 20,563 and 20,564, the title referring to the words "received a [blank] child" on the form filled out when a foundling was accepted at the hospital.[30]

The Foundling Hospital is the setting for Jamila Gavin's 2000 novel Coram Boy. The story recounts elements of the problems mentioned above, when "Coram Men" were preying on people desperate for their children.[31]

It appears in three books by Jacqueline Wilson: Hetty Feather, Sapphire Battersea and Emerald Star. In the first story, Hetty Feather, Hetty has just arrived in the hospital, after her time with her foster family. This book tells us about her new life in the Foundling Hospital. In Sapphire Battersea, Hetty has just left the hospital and speaks ill of it. The Foundling Hospital is mentioned in Emerald Star, although it is mainly about Hetty growing up.[32]

Published in 2020, Stacey Halls' The Foundling (or The Lost Orphan in the U.S.)[33] sees the main character, Bess Bright, leave her illegitimate daughter Clara at London's Foundling Hospital. The book was a Sunday Times Best Seller.[34]

See also

[edit]- Blackguard Children

- Child abandonment

- List of demolished buildings and structures in London

- List of organisations with a British royal charter

- Thomas Coram Foundation for Children

- Taylor White, a founding governor of the Foundling Hospital and its first Treasurer

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911, p. 747.

- ^ McCLure, Ruth K. (1981). Coram's Children: The London Foundling Hospital in the Eighteenth Century. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 205–210.

- ^ McClure, Ruth K. (1981). Coram's Children: The London Foundling Hospital in the Eighteenth Century. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 219.

- ^ Elizabeth Einberg, "Elegant Revolutionaries", article in Ladies of Quality and Distinction catalogue, Foundling Hospital, London, 2018, pp. 14–15, p. 15.

- ^ Exhibition guide: Ladies of Quality and Distinction. London: Foundling Museum. 2018. p. 2.

- ^ Godfrey, Walter H.; Marcham, W. McB. (eds.) (1952). 'The Foundling Hospital', in Survey of London: Volume 24, the Parish of St Pancras Part 4: King's Cross Neighbourhood. London: London County Council, pp. 10–24. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Copy of the Royal Charter Establishing an Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children. London: Printed for J. Osborn, at the Golden-Ball in Paternoster Row. 1739.

- ^ Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660–1851 by Rupert Gunnisp.129.

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives: A/FH/A/03/005/003, p. 79.

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives: A/FH/A/09/001/124-200 (Admission billets)

- ^ Mcclure, Ruth (1981). Coram's Children: The London Foundling Hospital in the Eighteenth Century. Yale University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0300024654.

- ^ Levene, Alysa (2007). Childcare, Health and Mortality at the London foundling Hospital, 1741–1800: "Left to the mercy of the world". Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780719073540.

- ^ McClure, Ruth K. (1981). Coram's children : the London Foundling Hospital in the eighteenth century. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 139–142. ISBN 0300024657. OCLC 6707267.

- ^ McClure, Ruth K. (1981). Coram's Children: The London Foundling Hospital in the Eighteenth Century. Yale University Press. pp. 137–139. ISBN 0300024657.

- ^ Correspondence of the Foundling Hospital inspectors in Berkshire, 1757-68. Clark, Gillian (Independent researcher), Berkshire Record Society. Reading: Berkshire Record Society. 1994. pp. Xiii. ISBN 0952494604. OCLC 32203580.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ McClure, Ruth K. (1981). Coram's children : the London Foundling Hospital in the eighteenth century. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 47. ISBN 0300024657. OCLC 6707267.

- ^ Lewis, Samuel. A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. S. Lewis & Co, 1837, "Cork" Section.

- ^ "Foundling Hospital". Jane Austen. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Foundling Hospital Records Orphan Train Records". 20 August 2016. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ "William Hogarth". Coram. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ a b Howell, Caro (13 March 2014). "How Handel's Messiah helped London's orphans – and vice versa". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ The Foundling Museum Guide Book, Second edition, 2009.

- ^ "Ashlyns School, Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire". Ashlyns.herts.sch.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Our story". Coram. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Coram's Fields and the Harmsworth Memorial Playground". Charity Commission. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ "The Foundling Museum, registered charity no. 1071167". Charity Commission for England and Wales.

- ^ "Thomas Coram Foundation for Children (formerly Foundling Hospital), registered charity no. 312278". Charity Commission for England and Wales.

- ^ "Foundling Hospital Archive". Coram Story. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Archive Catalogue". archives.coram.org.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Pugh, G. (2007), London's forgotten children: Thomas Coram and the Foundling Hospital. Tempus, Stroud: pp. 81–2.

- ^ "Coram Boy". The Guardian. 1 March 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Picturing Hetty Feather". The Foundling Museum. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "The Foundling". Stacey Halls. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Hall, Stacey (2020). The Foundling. Manila Press. ISBN 978-1838771409.

Bibliography

[edit]- Enlightened Self-interest: The Foundling Hospital and Hogarth (exhibition catalogue), Thomas Coram Foundation for Children, London 1997.

- The Foundling Museum Guide Book. The Foundling Museum, London, 2004.

- Gavin, Jamila. Coram Boy. London: Egmont/Mammoth, 2000: ISBN 1-4052-1282-9 (U.S. Edition: New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2001: ISBN 0-374-31544-2)

- Jocelyn, Marthe. A Home for Foundlings. Toronto: Tundra Books: 2005: ISBN 0-88776-709-5

- McClure, Ruth. Coram's Children: The London Foundling Hospital in the Eighteenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981: ISBN 0-300-02465-7

- Nichols, R. H., and F. A. Wray. The History of the Foundling Hospital (London: Oxford University Press, 1935).

- Oliver, Christine, and Peter Aggleton. Coram's Children: Growing Up in the Care of the Foundling Hospital: 1900-1955. London: Coram Family, 2000: ISBN 0-9536613-1-8

- Sheetz-Nguyen, Jessica A. Unwed Mothers: Victorian Women and the London Foundling Hospital. London: Continuum, 2012.

- Zunshine, Lisa. Bastards and Foundlings: Illegitimacy in Eighteenth Century England, Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2005: ISBN 0-8142-0995-5

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Foundling Hospitals". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 746–747.

External links

[edit]- Foundling Hospital

- 1739 establishments in England

- Buildings and structures completed in 1741

- Charities based in London

- Children's charities based in England

- Children's hospitals in the United Kingdom

- Former buildings and structures in the London Borough of Camden

- Organizations established in 1739

- Orphanages in the United Kingdom

- George II of Great Britain