Loli (district)

Loli | |

|---|---|

District | |

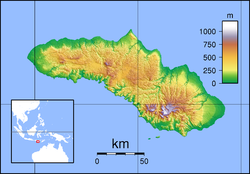

Location of Loli on Sumba | |

| Coordinates: 09°34′29″S 119°26′42″E / 9.57472°S 119.44500°E | |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Region | Lesser Sunda Islands |

| Province | East Nusa Tenggara |

| Regency | West Sumba Regency |

| Area | |

• Total | 132.36 km2 (51.10 sq mi) |

| Population (mid 2022 estimate) | |

• Total | 41,610 |

| • Density | 314.37/km2 (814.2/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 |

Loli, historically also known as Lauli,[1] is a district (kecamatan) of West Sumba Regency, East Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia.[2] The district consists of nine rural villages (desa) and five urban villages (kelurahan) and has its seat in Doka Kaka village. The district has a total area of 132.36 square kilometres (51.10 sq mi) and had a population of 41,610 as at mid 2022.[3] The most populous village in the district is Soba Wawi, which had a population of 6,092 people in 2020, while the most densely populated village was Wee Karou with a density of 731.67 people per square kilometre.[2] The district is the site of Gollu Potto, a statue of Jesus which is one of the main landmarks of the regency itself and the largest in the island of Sumba.[4][5]

History

[edit]

The district shares its name with the Loli clan residing in the town of Waikabubak (today a separate district) and the Loli countryside. Historically, it was also spelled as Lauli, a term which applied to the area.[1]

In precolonial times, the kabihu were autonomous groups without a central government, maintaining relations with each other through marriages and ritualized dispute settlement.[1] The disruption of such rituals, together with corruption, has been cited as a probable cause for the "Bloody Thursday" (kamis berdarah),[1] a battle fought in and around Waikabubak between members of the Loli and Wewewa clans on 5 November 1998, shortly after the Fall of Suharto.[6] It involved several thousand men, and officially resulted in the destruction of 891 houses and 26 deaths, although casualties are estimated to have been much higher.[1][7] Years later, during the elections for regent in June 2005, candidates from both Loli and Wewewe groups participated peacefully, which has been called a "public symbol of reconciliation".[8]

Culture

[edit]The Sumbanese language, a local language spoken in the region, has a dialect called Lolinese in the district. It can be combined with words from other dialects (e.g. Anakalangu) to form a special register called "ancestral words" (li marapu) which is used during rituals like marriage, prayers, and funerals.[9]

The district as of 2021 still had a high number of traditional houses,[10] with ancestral clan houses built on hilltops, for defensive purposes.[10][11]

The towns and villages around Doka Kaka are inhabited by the We'e Bangga people.[12] According to local folk stories, the creation of humans in the region was initiated by a mixing of sweat from the heaven and the earth itself. Behind the place of sun and moon, it was believed that there was an item shaped like a bottle named Gori Dappa Dada and beneath the earth, there was another item shaped like a plate named Piega Dappa. From the bottle, there were two drops of sweat falling to the plate, from which humans both male and female eventually emerged.[12]

The inhabitants of the villages within the district, while nominally adhering to other religions such as Christianity and Islam, are also following traditions from Marapu religion.[12] This "practice and belief system"[11] has traits of ancestor consultation and animism.[11] According to Marapu tradition, each village has the obligation to hold a Wulla Poddu ceremony every year.[12]

The villages are traditionally divided into smaller kampungs which are called poddu, and the primary social relationships of the residents are still influenced by a traditional clan system called kabisu. The kabisu system structures relationships based on the place of birth, where everyone from the same village is considered essentially descended from a single ancestor. Due to urbanization and internal migration of the district's population, some eventually settled in other villages while still maintaining a strong identity of their original kabisu.[12]

Administrative division

[edit]Loli has nine rural villages and five urban villages. They are listed below with their respective populations as of 2020.[2]

- Dede Kadu (4,200)

- Wee Karou (4,990)

- Soba Wawi (6,092)

- Ubu Pede (2,803)

- Bera Dolu (3,383)

- Doka Kaka (2,226)

- Tana Rara (1,302)

- Bali Ledo (1,143)

- Loda Pare (2,015)

- Wee Dabo (2,878)

- Dira Tana (4,036)

- Ubu Raya (1,975)

- Tema Tana (931)

- Manola (958)

Infrastructure

[edit]

The district as of 2020 had a total of 21 elementary schools, 11 junior high schools, 4 senior high schools, in addition to two vocational high schools. The district also had two tertiary education institutions as of 2020, all of them located in Dira Tana village.[2] In 2020, the district had a total number of four mosques, 395 Protestant churches, 11 Catholic churches, and one Balinese temple.[2]

Loli has a total road length of 135.41 kilometres in 2020, of which 88.01 kilometres have been paved with asphalt. Regarding the communication sector, the district was supported by the presence of 12 base transceiver station towers as of 2020.[2] The district had the highest internet speed for outlying and underdeveloped regions under the Bakti Program by the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology in 2022, with a recorded speed of 9.60 Mbit/s, compared to the slowest in Waimital, West Seram Regency with a recorded speed of only 106 kbit/s.[13]

Healthcare

[edit]Loli has one hospital, also located in Dira Tana village, three puskesmas, and one registered pharmacy.[2]

Malaria is a problem in the region, and in 2004 was ranked first among the public health problems in West Sumba Regency, being the leading cause of child mortality.[14] A study found that in 2005, around 25% to 30% of the population in Loli villages tested positive for malaria, with the majority of those under the age of 10.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Vel, Jacqueline A. C. (2001). "Tribal Battle in a Remote Island: Crisis and Violence in Sumba (Eastern Indonesia)" (PDF). Indonesia (72): 141–158. doi:10.2307/3351484. hdl:1813/54235. JSTOR 3351484. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Kecamatan Loli dalam Angka 2021". sumbabaratkab.bps.go.id (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2023.

- ^ "TAMAN WISATA RELIGI GOLLU POTTO WAIKABUBAK SUMBA BARAT". Website Resmi Sumba Barat (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Andryanto, S. Dian (9 July 2021). "5 Destinasi Wisata Patung Yesus di Indonesia, Paling Tinggi Ada di Pulau Samosir". Tempo (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Mitchell, David (June 1999). "Tragedy in Sumba". Inside Indonesia: The peoples and cultures of Indonesia. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Vel, Jacqueline A. C. (2008). Uma Politics: An Ethnography of Democratization in West Sumba, Indonesia, 1986–2006. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-25392-6. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Kirsch, Thomas G. (13 May 2016). Permutations of Order: Religion and Law as Contested Sovereignties. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-08215-6. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Keane, Webb (1997). "Knowing One's Place: National Language and the Idea of the Local in Eastern Indonesia". Cultural Anthropology. 12 (1): 37–63. doi:10.1525/can.1997.12.1.37. JSTOR 656613. Archived from the original on 27 July 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ a b Monna, Fabrice; Rolland, Tanguy; Denaire, Anthony; Navarro, Nicolas; Granjon, Ludovic; Barbé, Rémi; Chateau-Smith, Carmela (1 November 2021). "Deep learning to detect built cultural heritage from satellite imagery. – Spatial distribution and size of vernacular houses in Sumba, Indonesia" (PDF). Journal of Cultural Heritage. 52: 171–183. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2021.10.004. S2CID 240408600. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Mross, J. W. (2000). "Cultural and Architectural Transitions of Southwestern Sumba Island, Indonesia" (PDF). Cross Currents: Trans-Cultural Architecture, Education, and Urbanism. Acs4 2000 International Conference. Hong Kong. pp. 260–265. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Bulu, Anando Dedi (2017). Solidaritas dalam Ritual Wulla Poddu: Studi terhadap Bentuk-Bentuk Ritual Wulla Poddu di Kampung Tambera, Desa Doka Kaka, Kecamatan Loli-Kabupaten Sumba Barat (Bachelor thesis) (in Indonesian). Program Studi Sosiologi FISKOM-UKSW. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Ginting, Kristian (20 July 2022). "Berikut Catatan Ombudsman soal Program Akses Internet untuk Daerah 3T". Iconomics (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 21 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ a b Sauerwein, Robert W.; Trianty, Leily; Noviyanti, Rintis; Coutrier, Farah N.; Asih, Puji B. S.; Van Der Ven, Andre J.A.M.; Caley, Marten; Sumarto, Wajiyo; Luase, Yaveth; Syafruddin, Din (1 May 2006). "Malaria in Wanokaka and Loli sub-districts, West Sumba District, East Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 74 (5): 733–737. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2006.74.733. hdl:2066/49453. PMID 16687671.

Further reading

[edit]- Kábová, Adriana (20 June 2019). Kidnapping Otherness. Tourism, Imaginaries and Rumor in Eastern Indonesia (PhD thesis). Charles University.

- Rothe, Elvira (26 July 2004). Wulla Poddu: Bitterer Monat, Monat der Tabus, Monat des Heiligen, Monat des Neuen Jahres in Loli, in der Siedlung Tarung-Waitabar, Amtsbezirk der Stadt Waikabubak in Loli, Regierungsbezirk Westsumba, Provinz Nusa Tenggara Timur, Indonesien [Wulla Poddu: Bitter Month, Month of Taboos, Month of the Holy, Month of the New Year in Loli, in Tarung-Waitabar Settlement, Municipality of Waikabubak in Loli, West Sumba Governorate, Nusa Tenggara Timur Province, Indonesia] (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in German). Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

External links

[edit] Media related to Loli (district) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Loli (district) at Wikimedia Commons